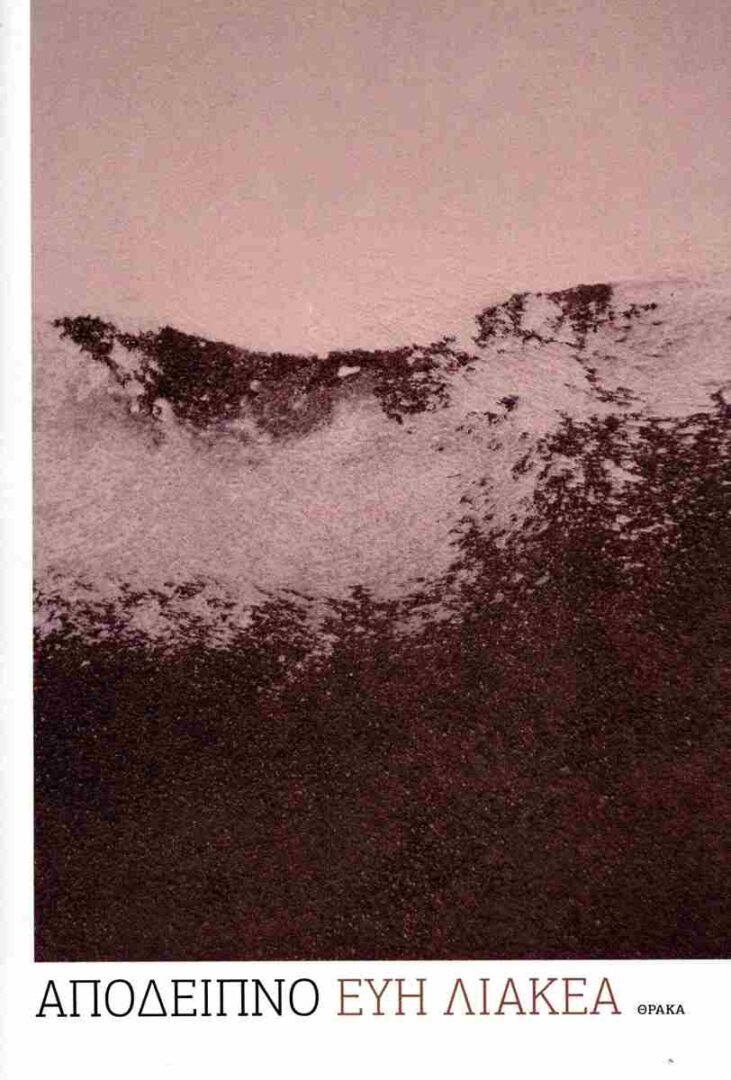

Evi Liakea was born in Kalamata in 1976. She studied psychology and music. She teaches the piano and is involved in collage and photography. In 2023 she published her first poetry collection Απόδειπνο (Apodeipnon) by Thraka.

Your first writing venture Απόδειπνο (Apodeipnon) (Thraka, 2023) received quite favourable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The word ‘apodeipnon’ in the title refers to a prayer that believers chant after supper to give thanks for what has already happened and to wish for what follows. Τhose sitting with me in the collection are mostly people who have died, in a coexistence, without lamentation, with the fact of death assimilated into the immutable present and into life.

In his review of the book, Dimitris Papakonstantinou commented on how the “small and insignificant” suddenly takes center stage, creating a parallel invisible world that captivates the reader. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

Little things comfort me. A pebble can encapsulate a wonder if I treat it as a sculpture, because that’s what it is, or as a material that hosts a painting. Conditions, humidity, light, where and how I find it or place it are the variables. In this variability, I sometimes perceive a snapshot as perfection, time expands and the object breathes the air of the eternal and timeless. This surprise that things offer if you observe them closely is a favourite subject of mine.

Another is unity. I try to move away from the opposing pairs of past – present, death – life, man – nature, etc., zeroing as much as I can the distance between what we have learned to recognize as dipoles. In this case, poetry is for me an exercise for my life. In the collection, my own people, elements of nature, writers, their heroes, and things are all elements with which I have felt connected and attuned and continue to illuminate inner spaces of mine.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

My language is simple. I have tried that the words, syntax and punctuation, whether in the prose poems or the more lyrical ones and haiku, leave room for silence, obey an inner rhythm and describe the feeling of things, which is my greatest concern. Clarice Lispector writes in A Breath of Life that feeling is the soul of the world. I am very moved by this phrase. I often feel that the poem exists naked and pure outside of me and, by simply passing through me, it drifts parts of mine in the form of words or sounds. Some words are even stored inside me in the voices of other people, and these voices come alive when the words are released.

Where does your poetry meet your painting? Where does the poetic meet the visual in your art?

It was an arduous journey until I realized that being fragmented, my pieces constitute a whole, and one that is under constant formation. When I work with collage, I draw from the chaos of disparate papers in search of some inner affinity with colours or materials. If I manage to find the connection, the result is usually a representation of a mental landscape, a representation, as I already mentioned, of my inner space. More or less it happens every moment since these are my thoughts, my feelings, what I observe around me, what I remember, etc.; the fact that at times I focus on one and at times on another does not mean that at the same time I cease to exist in the rest.

I’m certainly very lucky to have studied the piano and I work with visual arts, because that way I don’t separate the arts. Music, visual arts and poetry make up a kind of vector mirror of myself. But regardless of me, I think any work, from whatever art, whether you approach it as a creator or a recipient, requires a very high degree of synaesthesia. I reckon that words in poetry struggle to be perceived as not only notions, but also as images and sounds.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do social media play in the way people read and write?

I understand that a publishing house as a business may face hard times to survive. However, I find it both extortionist and racist that there are publishing houses asking four times the cost of a publication. In addition, meeting people in the book market, which, of course, usually follows the first publication, is very useful in reducing the time it takes to evaluate a work. Otherwise, this time also depends on luck, just as it depends on the politeness of a publishing house in case of rejection. The internet indeed allows for a basic familiarity with people you can turn to or who offer their help on their own initiative. In terms of the influence of the medium, especially when sources are carefully selected, you can become acquainted with masterpieces that would otherwise have eluded you forever, as well as with many different translations of a work and data collected, changing the respective approaches.

For me the problem lies in that we are inundated with poems or other works, which at times makes me feel as if I am in a group art exhibition that no one curated or in a concert with such disparate compositions that I find it difficult to understand not only what is good and what is not, but also what I need at the moment. Even at my home library, I need time and sobriety to pick the right book at the right time. And unfortunately, all these different voices, one on top of another, often hide my own voice that comes like a whisper and I have to close my ears to hear and understand it.

How do contemporary Greek poets converse with world literature? Where does the local and the national meet the global and the universal?

I have the impression that national identity is hardly discernible in contemporary art; I reckon that it is limited to periods in which a kind of ‘restoration’ is attempted, as for example may happen or is already happening with Palestinian artists in Gaza. In what the rest of us are experiencing, which in my view is a new type of fascism, I see a more active role of movements, which are strengthened, far beyond the narrow confines of one place, by a global network of movements against all forms of violence, racism, exclusion, etc. In other words, I consider that art is now more easily organised globally as a political act, even if this osmosis is, I hope only temporarily, possible through its fragmentation into categories.

On the other hand, the freedom to write regardless of nationality, e.g. haiku, a national-religious poetic genre, which I mention because I love and use it, puts the national at the service of the personal and at the same time the universal. Yet, I feel the need to return to what for me is the most fascinating and comforting element of art – unity in time and space, in the way Matthew Arnold describes it in Dover Beach.

*Ιnterview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE