Dr Stephen G. Miller is Professor emeritus of Classical Archeology at UC Berkeley and Director Emeritus of Berkeley’s excavations in Nemea, Greece, who, after years of hard work, made headlines worldwide for the uncovering of the ancient athletic site where Panhellenic games were held. He is also former Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (1982-87), founder and honorary President of the Society for the Revival of the Nemean Games and honorary President of the American Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Having arrived in Nemea in 1973 and after more than 20 years of extensive and systematic excavations, Professor Stephen Miller uncovered the Sanctuary of Zeus and the ancient stadium that was built 400 m SE of the Temple. He has published a great number of scholarly publications, and popular articles, with a focus on the Nemea excavations. In 2005 he was appointed Grand Commander of the Order of Honour by former President of the Hellenic Republic Karolos Papoulias, and was also proclaimed Greek citizen.

Dr Miller was interviewed* by Greek News Agenda on the Nemea excavations, the foundation of the Society For the Revival of the Nemean Games and the cause of repatriation of Parthenon Marbles.

Dr. Miller, you were the director of excavations at the archeological site of Nemea, which have lasted for years. How did you feel when you uncovered, after so many efforts, the site where the Panhellenic games were held?

When I arrived at Nemea in 1973 to begin my work, there was one visitor all summer long to the three columns of the Temple of Nemean Zeus that had remained erect since their construction about 330 B.C. They were guarded by thistles and thorns.

Now, 45 years later, I look out the window of my office and see nine columns surrounded by a revival of the ancient sacred grove of cypress trees, and I see thousands of visitors. In the last three years, during the 26 months that the site was open, there has been an average of 3,626 visitors each month. They enter a site created by my purchase of property (about 40 acres) in the name of the Greek State, but with archaeological rights retained by the University of California. Three roads have been closed and the museum built and given to Greece on May 28, 1984. In that museum, and on the site and in the stadium, my discoveries are on display to the visitor (of all nationalities) who leaves Nemea knowing a little more about his own Hellenic heritage. This is very satisfying. My grandfather said that I had been given life for a purpose. I believe I found it.

Minister of Culture Thanos Mikroutsikos and Dr. Stephen Miller embrace as the latter turns over the Stadium to the former (1994)

Minister of Culture Thanos Mikroutsikos and Dr. Stephen Miller embrace as the latter turns over the Stadium to the former (1994)

What were the main challenges you faced during the excavations?

The first challenge was, and is, funding. In the half year while teaching at Berkeley, I had to find donors who would support my work. I was fortunate that so many shared my curiosity. Their names are on a series of marble plaques in the entrance to the museum.

The next challenge was to develop a local support and excavation team. Again I was fortunate, although there was some local opposition, but enough good and competent people emerged. Their help was critical to my success.

There was a constant challenge, in a village of 300 people which was not then fully electrified, to find housing for my American students. Most reacted positively and some were even sorry to leave Nemea at the end of the season.

Finally, there were the relationships with the representatives of the Ministry of Culture from which I needed permission to excavate each year. There were unhappy exceptions, but most of those people regarded me as a colleague who deserved their support, especially since the American School of Classical Studies at Athens gave me its blessing.

The Temple of Nemean Zeus from the southwest, 2013

The Temple of Nemean Zeus from the southwest, 2013

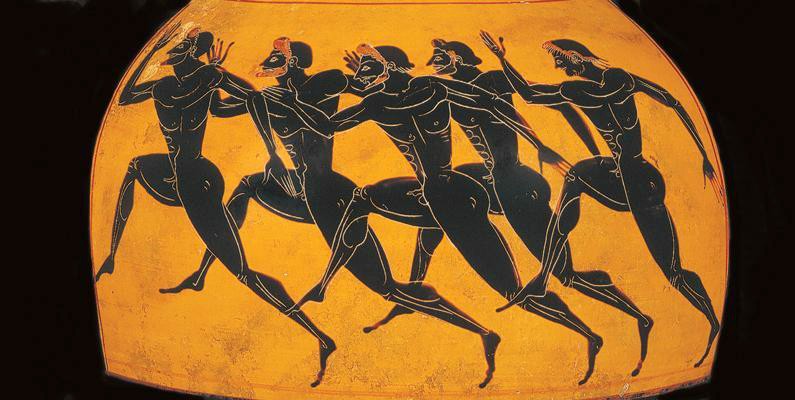

Can you tell us something about the ancient Nemean games? Who were the participants?

Nemea was important in antiquity only for the Games. There was no permanent settlement here, no city-state in what was a marshy land every winter. The name comes from the verb “nemo” which means to graze (sheep, goats, etc.); Nemea was a good place for shepherds, but not for farmers.

In the summertime, every two years, the scene changed with the advent of thousands of athletes, and trainers, and spectators, and merchants for the Nemean Games which were a part of the Panhellenic (All-Greek) cycle of the Olympics, the Pythian Games at Delphi, and the Isthmian Games near Corinth.

Among other similarities, these sites shared a Sacred Truce, an Ekecheria, that allowed people to travel to and from the games in safety. Thus, for example, Athenians and Spartans might be throwing spears at one another one day, and the next be running naked side-by-side down the track of the stadium here. The truce only held for about a month each year, but it was the first time in recorded history that a whole nation entered a truce annually on a regular basis. Our excavations have revealed ups and downs in the execution of this idea, and that may be the most important part of my work.

You are the founder and honorary President of the Society for the Revival of the Nemean Games. What is the goal of your society?

You are the founder and honorary President of the Society for the Revival of the Nemean Games. What is the goal of your society?

Our goal is the participation, on the sacred earth of Greece, of anyone and everyone, in games that will revive the spirit of the Olympics. We will achieve this by reliving authentic ancient athletic customs in the ancient stadium of Nemea.

Statement of the Purpose of the Society, December 30, 1994

Our Society has two basic guiding principles: authenticity and participation. We do not insist on complete authenticity: we do not run naked and we allow women to run. But all have to dress in plain ancient tunics and run barefoot, thus emphasizing our basic common humanity. Further, to change clothes in the ancient locker room, to walk through the entrance tunnel, to place toes in the same starting blocks where the ancients placed theirs 2,350 years ago, means a direct physical contact with ancient Greece. It is a learning experience, and shows that the ideals of the ancients still live.

The revival of the Nemead began in 1996 and the Games take place every four years. Are you planning to be in Nemea during the 7th Nemead that will take place in June 26-28 2020?

Since my retirement from UC Berkeley in 2004, I have lived much of every year here, in Nemea, working on research and publications, and the revival of the Games. Yes, I shall be here for the 7th Nemead – God willing – but probably working as a slave rather than appearing as an athlete.

And a final question: what is your opinion on the issue of the return of the Parthenon Marbles in Athens?

And a final question: what is your opinion on the issue of the return of the Parthenon Marbles in Athens?

The Parthenon is certainly one of the greatest achievements of our human race – some would say the greatest symbol of our common Greek heritage regardless of our nationality. It is the physical representation of one of the highest achievements of civilization. I look at it and see Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides and Aristophanes and Thucydides and Socrates. I see the young Plato looking up at the new building – did it inspire him to tell us about his mentor?

To have this monument, this symbol of cultural accomplishment broken up and scattered around the world, to make its totality inaccessible to our society, says all too much about our own civilization.

I am not advocating that the Parthenon should be moved to London, but let us put it back together where Pericles and Pheidias built it nearly two and one half millennia ago. Can we not respect our own pan-humanity?

*Interview by Marianna Varvarrigou (Images courtesy of nemeangames.org)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Sharon Gerstel: “Byzantine History opened my eyes to a culture that has long been marginalized in our studies”; Reading Greece | Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek; Study Archaeology in Greece: English-taught Undergraduate and Postgraduate Courses