A recent draft bill on Sharia law aims to limit its application in Western Thrace, home of a Muslim minority in Greece. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has recently stressed that the bill will address “shortcomings and inequalities affecting the minority population of the country”, while Education Minister Costas Gavroglou has told the relevant parliamentary committee that “the specific legislation is a step towards equality and democracy, within a complex European context and a framework for respecting the Muslim minority in our country”.

The draft bill, filed by the ministry of Education, is expected to be tabled in the parliament plenum on Thursday 11.1.2018. According to the new law, family law disputes (divorce, inheritance) for Muslim minority members who have been married in a religious ceremony will from now on be resolved in Greek civil courts, unless both sides in the dispute agree before a lawyer to have their differences resolved through a mufti (interpreter of Sharia law).

Greek News Agenda spoke* with Konstantinos Tsitselikis, Professor at the Department of Balkan, Slavic & Oriental Studies of the University of Macedonia (Thessaloniki, Greece) about the legal status of the Muslim minority in Western Thrace, the obligatory application of the Sharia law and its impact on the lives and human rights of the Greek Muslim communities of the region. Tsitselikis argues that the new law constitutes a positive step that ensures access to civil law, stressing that “minority rights should not infringe fundamental human rights, the pillar of our democracy” and that “Sharia law should be implemented in line with human rights, values and norms.” He adds that dealing only with issues of language and religion, while ignoring the economic factors that exclude large parts of the minority from mainstream Greek society, is not enough to achieve the full integration of the minority populations.

Professor Tsitselikis’ main academic interests concern human and minority rights and international law. He has also worked for the Council of Europe, the OSCE, the UN, the EU in human rights and democratisation field missions and has been president of the Hellenic League for Human Rights. In the past years he has conducted research on minority foundations of the Greek Orthodox minority in Turkey and the Muslim minority in Greece.

Would you like to tell us a few words about the legal status of the Muslim minority in Western Thrace? What are the conditions that led to the adoption of the Islamic law and its preservation to date?

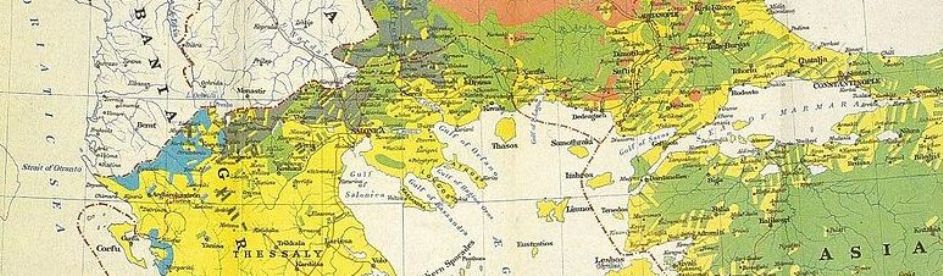

At the end of the Greek-Turkish war of 1919-22, the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Turkish Republic, the Lausanne Conference adopted measures sanctioned by international law that effectively involved ethnic cleansing in a bid to achieve homogeneous nation-states in Greece and Turkey. The population exchange between the two countries was decided as a counter-weight to the Greek Orthodox population already expelled from Asia Minor. Over 400,000 Muslims of Greece were forced to migrate to Turkey. However, under the Convention of Lausanne (January 1923), the Muslims of Western Thrace were exempted from the population exchange, as were the Greek Orthodox of Istanbul (also the Greeks of the islands of Imvros and Tenedos).

The subsequent Treaty of Lausanne (July 1923) guaranteed special minority rights to the non-Muslim Turkish citizens in Turkey and to the Muslim citizens in Greece who had been exempted from the population exchange. This special legal protection concerns, since 1923, education rights (bilingual minority schools), protection of community properties (waqf/vakif/vakoufia) and religous freedom. Religious freedom regards prayer houses (mosques and mescits), religious functionaries (imams) and religious leaders, the muftis. The three muftis of Thrace also acquired special jurisdiction over family and inheritance matters. The jurisdiction of the mufti to apply Sharia law in Thrace stems from the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). The treaty, which is the cornerstone of minority protection up to date, states in Article 42 Paragraph 1: “The [Greek] government undertakes, as regards [Muslim] minorities in so far as concerns their family law or personal status, measures permitting the settlement of these questions in accordance with the customs of those minorities.”

The legal content of Act 2345 (1920) on the authority and status of the muftis did not change even when the law was replaced by Act 1920 (1991), which retained both the substantive law and the procedure of the 1920 act. Under this regime, the mufti system has survived, albeit with some limitations. Within their areas of jurisdiction, the three current muftis of Thrace (serving Komotini, Xanthi and Didymoteiho) have jurisdiction over family law and inheritance disputes between Muslim Greek citizens. Often the Greek courts consider the mufti’s jurisdiction as exclusive and obligatory and this has negative impact over the Muslims of Thrace.

How did the obligatory application of the Sharia law impact the lives of the Greek Muslim community? Which segments of the population were the most affected?

The obligatory application of Islamic law has taken two forms: When the civil court denies accepting an application filed by a Muslim (in most of the cases lodged by a woman applying for divorce) and remands the case to the mufti; and when the civil court denies applying the civil law on inheritance as regards a public will (overturning thus the wish of a Muslim testator who drafted a will according to the civil code).

Therefore, the most affected segments of population among the minority of Thrace are women and all those who draft a will according to the civil law. In a broader sense anyone, regardless of minority affiliation, can be harmed due to lack of legal certainty: Ownership over inherited properties could be overturned as there are no clear norms on the validity of wills. Lastly, children of divorced parents, who after certain age are always placed under custody of the father, have been largely affected.

What would you answer to the claim that the application of Sharia law is necessary for protecting the minority´s religious rights?

Often, the implementation of Islamic law is considered to be a part of the minority protection system. If this is true, Islamic law should not contradict fundamental human rights that also protect the status of the minority. Minority rights cannot be implementable without the general framework of human rights within which are functional. Therefore, minority rights cannot infringe fundamental human rights, the pillar of our democracy. Sharia law could be implemented in line with human rights, values and norms.

How do you evaluate the changes introduced by the bill? Does it ensure that the Islamic law will be applied only as an exception to the Civil Code and following the expressed will of all parties involved?

The draft bill, which introduces amendments to the law on the muftis, constitutes a positive step towards resolving this ‘legal anomaly’, and ensuring equal access to civil law. Islamic law will be applicable only when both parties agree on it.

It is worth noting that this change has been triggered by a case adjudicated by the Greek courts and then by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg. The case was pending before the First Section of the European Court since 2014, and was referred to the Grand Chamber: a Greek Muslim in Thrace had drafted a public will according to which his wife would inherit all of his estate. As they did not have any children, after he passed away, his widow acquired the entire estate. The public will was then challenged by the sisters of the deceased, on the grounds that Sharia law -according to which they are heirs on the ¾ of the deceased’s property- should be obligatorily implemented. While the first instance court and the Court of Appeal of Thrace upheld that the public will is valid and Sharia law cannot be implemented without consent, the Supreme Court of Greece upheld the opposite: That Sharia law is the exclusive law applicable on all Muslims of Thrace in the framework of the minority protection law.

The Grand Chamber of the Court of Strasbourg heard the case on the 6th of December 2017; this hearing set off a chain of announced changes of law on the muftis and the Islamic law applicable in Thrace. In November the Prime Minister announced from Komotini, Thrace that the Sharia law will cease to be obligatory and will become voluntary to those who wish to follow it.

Do you believe that in the long run Sharia law should be abolished altogether?

To have Islamic law be a part of the Greek and the European legal system two conditions should be met: First, that there is no infringement on fundamental human rights; second, that the members of the minority are free to choose the one or the other law.

The government is also faced with two options: First, to abolish by law, in a kind of ‘sudden death’, Sharia law and the mufti courts; second, to impose the aforementioned conditions in the application the Islamic law. The government seems to have chosen the second option, and I believe that in the near future only a small percentage of cases will continue to be adjudicated by the mufti: the majority of the members of the minority will opt for civil law. Women will play a significant role in this change, and this will amount to a big step towards their emancipation.

However, Islamic law as applied by the muftis is only one aspect of the problem. The way the muftis are appointed is also an issue that has remained unresolved for many years and needs to be dealt with. It seems that the government is considering opening the door to the election of the muftis by the minority.

What other legislative actions and/or policies do you think would contribute to the further integration and equal treatment of the Muslim minority of Thrace?

The Muslim minority of Thrace should be seen as a segment of the Greek society, not to be subjected to discriminatory treatment or special measures that do not uphold the rule of law. Of course, some special measures are necessary in order to ensure the equal treatment of vulnerable groups like the Muslim minority. However, characteristics such as ethnic and national identity, language and religion are not the only ones that define the minority today.

Social exclusion and poverty shape the canvas on which minority characteristics are developed. Treating only language and religion and ignoring the economic factors that exclude large parts of the minority from the mainstream Greek society does not help integration. In order to achieve integration we have to reach acceptance of the “other” as well as to guarantee equal opportunities for all, without barriers on religious and national identities.

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi

Read more Konstantinos Tsitselikis papers here. Read more about Konstantinos Tsitselikis book on Old and New Islam in Greece – From Historical Minorities to Immigrant Newcomers (Leiden/Boston, 2012).

See also: Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Issues of Greek – Turkish Relations; Major International Treaties Concerning Greece; The Economist: Greece prepares to do away with compulsory sharia in Western Thrace