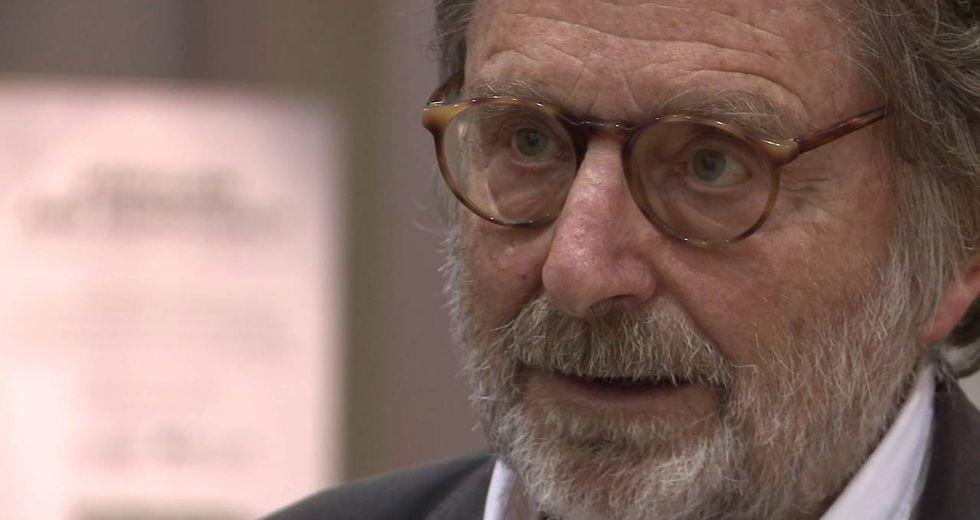

Sociologist Nikos Mouzelis, emeritus professor at the London School of Economics, talked to Efimerida ton Syntakton daily (05.05.2019) and Vassilis Kalamaras on the occasion of the publication of his latest book “Perspectives on the Future: Capitalism, Social-Democracy, Social-State ” (2018, Alexandria Publications, in Greek). Nikos Mouzelis talks about the future of capitalism and the role of Germany and France in the European project. Greek News Agenda reproduces part of the interview in English.

At the presentation of your latest book you noted that while you cannot foresee the future, capitalism will not collapse in the near future. On what grounds do you base this prediction?

Following the 2007/8 global crisis, prominent intellectuals of the Left anticipated that more crises will follow and that the capitalist mode of production would collapse in the near future. I think that capitalism, although it will not survive forever, will not collapse in the short / medium term. This is because, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and within the global neo-liberal system, three capitalist subsystems have been dominant: the neo-liberal system, whose main representative is the US, the authoritarian capitalist system one of China and the semi-social democratic system of the EU, which, despite the strict fiscal austerity imposed by Germany, remains social democratic because its social state is the most developed in the world, while political and cultural rights survive.

In this context, the global capitalist system will be with us for many years to come, since those who control the means of production and the means of domination are much more powerful than the forces (social movements, unions, mass movements etc) that want to subvert it.

Photo by Pixabay, Source: Pexels.com

As far as social-democratic capitalism is concerned and the way it has functioned in the Scandinavian countries, we bear witness to the impressive rise of the Far Right and the decline of Social Democratic parties. On what grounds do you base your optimism for the resurgence of social democracy?

The way social democracy developed during its so-called golden era in Southwestern Europe managed for the first time in the history of Modernity to humanize capitalism to a certain degree. State mechanisms managed to reduce inequalities and create a developed social state.

We witnessed, in other words, the extension of civil, political and social rights down and across the social pyramid. But then the opening of global markets, especially in the 80s, eased the autonomy of the nation state, since the state was no longer able to control multinational capital within national borders. Strict state control led to the flight of funds to countries where conditions were more favorable for investors.

What we thus have is an intense imbalance of power between capital and employment. In this state and with the end of the Ford model of industrialization that shrank the core electoral base of social democracy, i.e. the industrial proletariat, social democratic parties had to reach out wider and approach the values and practices of neoliberalism. For certain analysts this was necessary for the survival of democracy. For others it was a betrayal.

Nevertheless, I believe in a possible recovery of social democracy through an alliance with political forces that oppose both neoliberalism and nationalistic populism, since the inequalities that the one creates directly feed the other. Forces such as the radical left, ecological, politically liberal and other middle ground parties could provide a serious barrier to the two barbarisms of today’s globalization.

Our country has been through a decade of fiscal adjustment programs, with Germany being the dominant player. How stifling is its dominance?

Germany’s dominance remains stifling, because at the moment the rest of the EU countries are not ready for the establishment of a supranational federation. Of course, both Germany and France agree on European integration, but they have a very different vision of unification.

Merkel’s strategy aims at a step by step consolidation by maintaining the current status quo, meaning a situation where economically strong countries and especially Germany will continue to accumulate huge surpluses while the European regions accumulate deficits. This means a systematic transfer of resources from the less competitive economies of the South to those of the North.

Despite this negative situation, there are no serious attempts for instruments of redistribution. Assistance to the poorest countries is negligible compared to resources directed towards the richest.

On the other hand, Macron’s strategy is different. Despite his neo-liberal policies in his country, the French president aims to create a European federation based not only on competition but also on solidarity.

He stresses, for example, the need for serious redistributive mechanisms to mitigate the North-South divide. Of course, due to his country’s economic difficulties, Macron cannot impose his own program, thus Germany will probably manage to impose its own plan, which may lead to the dissolution of the EU.

This is something which is neither in France’s nor in Germany’s best interest. The only way to reduce the power imbalance between the two main players in the European arena is an alliance between France and South European countries, because their interests converge. For the time being, however, this does not seem to progress.

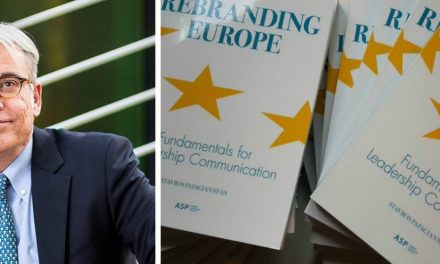

Photo by David Holt, Source: Flickr.com

Brexit is now a fact. Do you think there are risks as to the EU’s dissolution?

I don’t think that Brexit threatens the EU with possible dissolution; quite the opposite. For a number of reasons, it may lead to more cohesion. England always wanted a large market, nothing more, constantly creating barriers for those who aimed at political and social unification, and persistently demanding an “a la carte” participation. Moreover, she did not want Brussels bureaucracy mingling in her domestic affairs.

Brexit has already caused serious problems in England, such as the outflow of companies to Europe. There is no doubt that it will devalue the country, at least in the economic sector. In the medium term, England will develop into a second / third-class economy. All of the above will make Eurosceptics aware of the negative Brexit effects. It’s clear that Brexit does not suit England, but it certainly favors EU cohesion.

F.K.

Read also: Associate Professor Antonis Tzanakopoulos on Greek Foreign Policy, Brexit and Globalisation, Costas Douzinas: “If Europe does not change fast, then the ‘Finis Europae’ is closer than we think”.