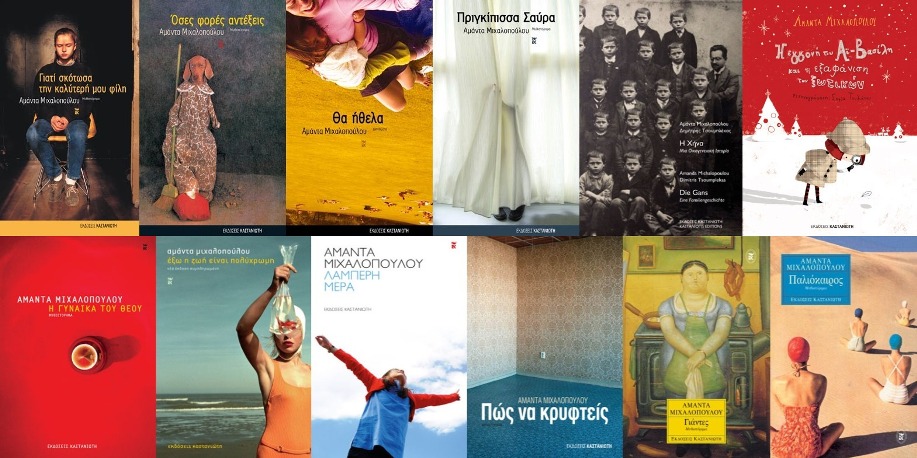

Amanda Michalopoulou was born in Athens in 1966. She is the author of six novels – God’s wife (2014), How to hide (2010), Why I killed my best friend (2003), Paliokairos (2001), As often as you can bear it (1998), Yantes (1996) – three short story collections – Shining Day (2012), I’d like (2005), Life is colorful out there (1994) – and a series of children’s books. Her stories have appeared in Harvard Review, Guernica, PEN magazine, World Literature Today, Words Without Borders, Asymptote, The Guardian among others.

One of Greece’s leading contemporary writers, Michalopoulou has won the country’s highest literary awards, including the Revmata Prize (1994), the Diavazo Award for her novel Yantes (1996) and the Athens Academy Prize for her short story collection Shining Day (2013). Her short-story collection, I’d Like, was longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award by the University of Rochester, USA. Her novel Why I Killed My Best Friend was published in English by Open Letter in 2014. Her books have been translated in twelve languages.

Amanda Michalopoulou spoke to Reading Greece* about how her writing evolved during the years, literature’s ‘innate quest for form’ and non-linearity in a post-modern era, the way ‘psychogeography’ plays into her writing and how ‘what is embedded in our life is also embedded in our fiction’. She also comments that in order to “grasp the human soul, the Greekness of the experience, we’d better aim to the universal feeling of what it means to be in crisis, in pain, or at a loss” and how the current crisis may act as “a big opportunity of self- and social exploration and revaluation”.

It’s been twenty years since your first novel Yantes, while your work also includes short stories and children’s books. How would you characterize your writing career so far? How has your writing evolved during the years?

As we evolve in life our writing changes too. It happens to everybody. In my case I feel writing has been less sarcastic with time, I probably lost the audacity of my youth and replaced it with other values. I am less cruel with my characters and it is difficult for me to describe violence. I guess there is so much violence around that I want my writing to be a sanctuary. People hurt themselves of course in my fiction and they hurt others but I am more compassionate with them, hopefully in life too. We bring to the writing, in a fictionalized process, themes and ideas that are important to us. As for me I try to be more to the point, focus to the story, exclude what doesn’t belong to it naturally.

“…There isn’t such a thing as a linear life anymore, and fiction always imitates life…”. Would you say that your novels fit in the category of metafiction? Is non-linearity a technique best suited to the particularities of a post-modern era?

I feel every book dictates the way it would be written, in stylistic terms also. If I start with an idea like “I am a metafictional writer” then I don’t respond to the inner life of the work, I just make judgments and try to respond to them, and consequently I block the creative energy of what is to be written. And I have done this a lot in the past! Writers write a book to find out what will happen next and in this they remind us of the reader’s procedure, this unsure step towards an unknown text, when you start reading a book, like walking on a path that someone else has dug for you and which is not always obvious.

Now about linearity; I believe that we are not living the way mankind used to live, finish something and then start something else. You open a link in a text that leads you to another link and then you don’t remember how it all started. Like free association of ideas. This can be enriching but it can also be an obstacle to thought and to responding to life with alertness and mindfulness. It is always interesting to see how literature responds to this innate quests of form. I am thinking about Borges and Bioy Casares, about Cortasar and Italo Calvino and Clarisse Lispector, some of my favorite writers who dealt innovatively with questions of time and space and form. I follow their example.

You have said that almost all of your books are finished or, at the very least, written partly outside of Greece. Does ‘psychogeography’ play heavily into your writing process? How does the theme of displacement functions in your work?

Displacement in space creates also a psychological displacement, like if you look at yourself from above or behind. This is what I look forward when I write. Not to think about others, about what they would think about me. Be in a neutral environment where I can research again what it means to be human and how to function in the world. When it happens it is pure creation, from the deepest source of creativity, from our inner hidden landscape of ideas and wishes. Of course the most mature way is to achieve this wherever you are, to feel free even in your small flat, in your neighborhood. I am not there yet.

Do you feel that your writing has a Greek or a Mediterranean aspect to it or that you belong to a national literature? What do you consider to be the appeal of Greek writers abroad?

I don’t believe in national literature. I don’t read Kafka because of his nationality but because of what he brought to the exploration of the human fear and loneliness. Some writers write about a specific island or town, I have done that too, but if you write trying to sell your country, the Greek salad that your characters are eating, then it is forced and not authentic. I think Elena Ferrante is so much appreciated not because of what she writes about life in Italy in the 50s and Mafia and poverty, evocating the life of the South, but because of the way she writes. The style makes the issue bright or dull. Same with Kazantzakis or Elytis. Same with amazing writers and poets of today like Ersi Sotiropoulou, or Dionysis Kapsalis. If we want to find out what happens in Greece we can read the news. But to grasp the human soul, the greekness of the experience we’d better aim to the universal feeling of what it means to be in crisis, in pain, or at a loss.

“When I think of Athens, my mind always goes to Exarchia […] I may live in the suburbs now, but to write I book, I always go to my small office in the city center, where the Athenian life really takes place […] Sometimes I feel ashamed to witness despair from a distance, but that’s my job”. How has the current socio-economic crisis been embedded in your books?

What is embedded in our life is embedded in our fiction, not always in obvious, pragmatic ways. I wrote a short story collection, “Bright Day”, about people who miss something, who have an experience of loss. I invoke the crisis, but not as a journalist. This would be an article then, not fiction. I also wrote a novel in 2014, “God’s wife”, about how the wife of God questions Creation. This would seem irrelevant but it isn’t. This is what every Greek went through the last couple of years; they questioned their existence. If you break the ice of surface and go deeper very strange questions and stories come around. Crisis is ultimately existential.

You have recently written a number of articles for ‘Tagesspiegel‘ commenting, among others, on current developments in Greece. Where is our country heading to? What is to be expected at a cultural and intellectual level?

I honestly don’t know. What history has taught us is that life goes on in circles. This is a big wave now and it will probably calm down at a certain point, only to come up again later in history. Most important is how these waves are received, what they teach us about survival. And also about ambition, corruption, honesty and responsibility. If we get out of this crisis wiser, then it is a big opportunity of self- and social exploration and revaluation.

Now about writing at Tagesspiegel; it is difficult to write about your country and keep a healthy balance. Not being too judgmental but still giving some honest information and also provide what is most difficult, an explication about why Greeks are the way they are and how politics and social institutions shaped their experience and their lives. I am grateful I was given this opportunity to write as Greek and as European and explore in written form what it means to be Greek today.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE