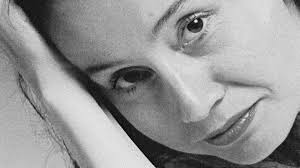

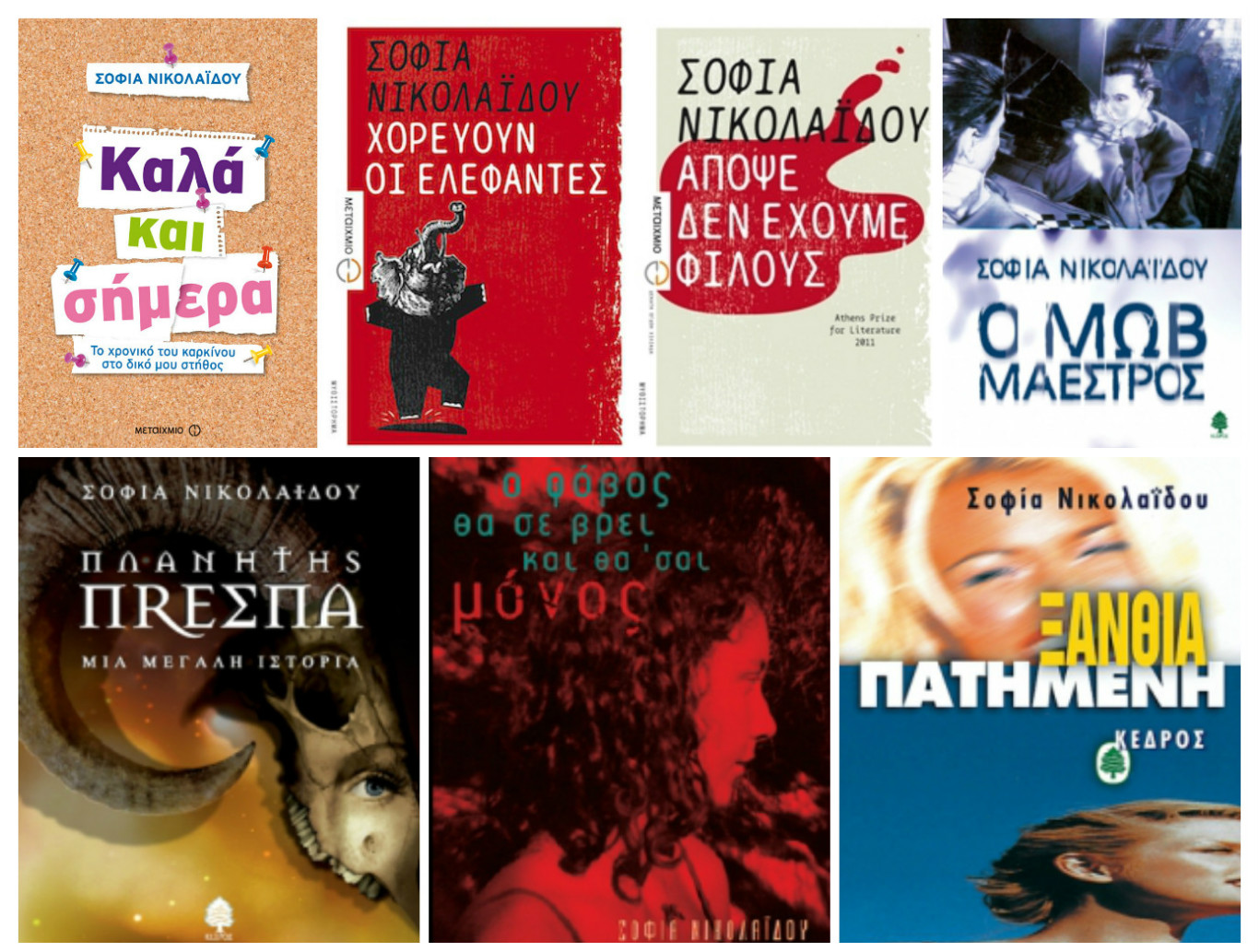

Sophia Nikolaidou was born in Thessaloniki in 1968. One of modern Greece’s most significant young novelists, she has published two collections of short stories – Fear Will Find You and You Will Be Alone (1999) and Blonde Run Over (1997) – and four novels – Planet Prespa (2002), The Purple Maestro (2006), No friends tonight (2010), The Scapegoat (2012) – which have been translated into eight languages. She has also published a non fiction novel So far so good (2015), studies on creative writing and on the use of ICT in education and translated ancient Greek drama into Modern Greek. She teaches literature and creative writing and writes criticism for various newspapers, including Ta Nea. Her novel, No Friends Tonight won the 2011 Athens Prize for Literature, and The Scapegoat was shortlisted for the 2012 Greek State Prize for Fiction.

Sophia Nikolaidou spoke to Reading Greece* about how The Scapegoat, recently translated in English, captures the political adventure of Greece and the way the country’s difficult past is represented in contemporary Greek literature, drawing interesting correlations to the present. She also explains the impact her fight with cancer had on words, in the way she “perceives and names things”, while commenting on the general trend towards a more realistic approach in literature.

In her capacity as teacher, she talks about the role and prospects of the Greek educational system, noting that young people should be taught that reading literature can be ‘a gratifying experience’. “From the moment you get acquainted with intellectual pleasure, there is no way back. And as you know, when you breathe through art, you don’t age easily. You continue to have that creative mood regardless of age and problems. And this amounts to the greatest gift”.

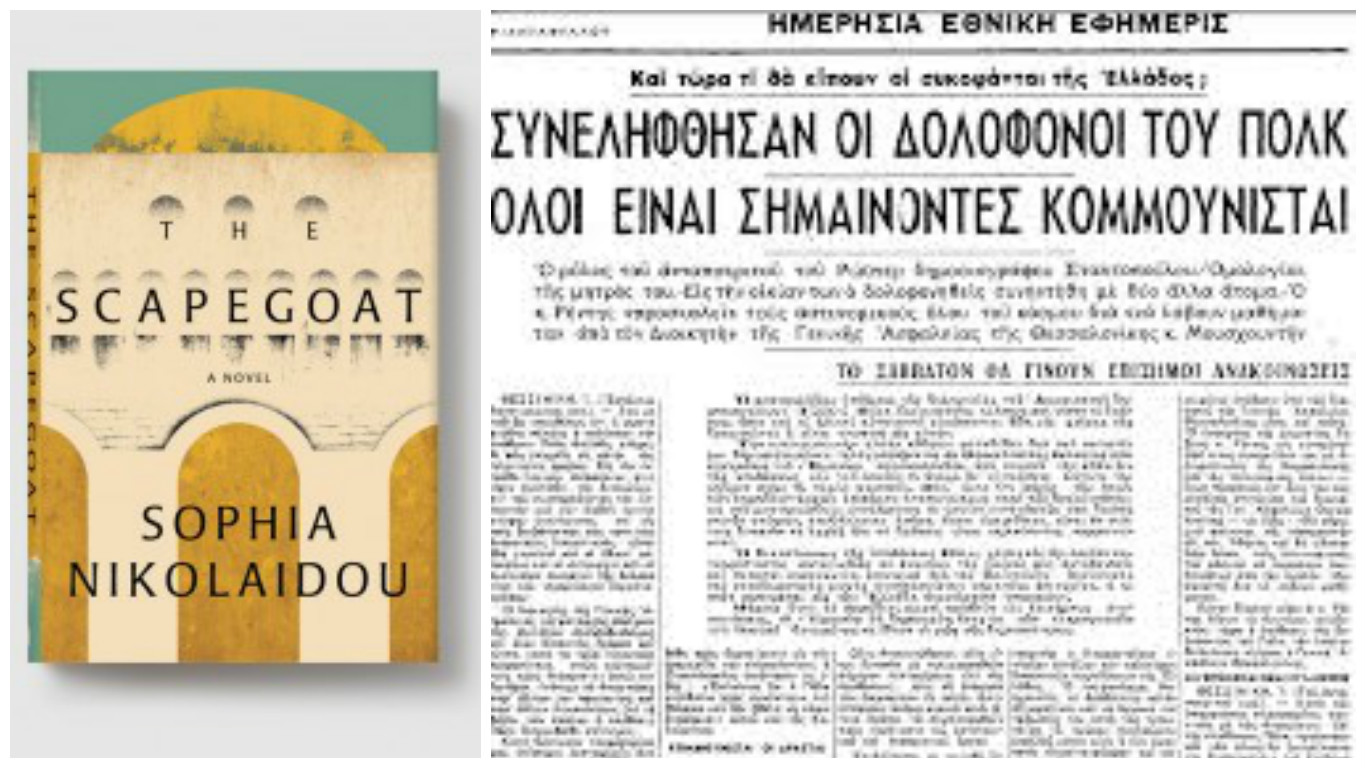

The Scapegoat – recently translated in English – delves into Modern Greek political history, bringing together the Greece of the post-World War II era with the Greece of today, a country facing dangerous times once again. Tell us a few things about the book.

The Scapegoat is the second part of a trilogy about the adventure of a city (Thessaloniki), a country (Greece), an era (20th-21st centuries). It unfolds two narrative threads in two different historical periods (a now 2010-11 and a then 1948-49), which intertwine in the end.

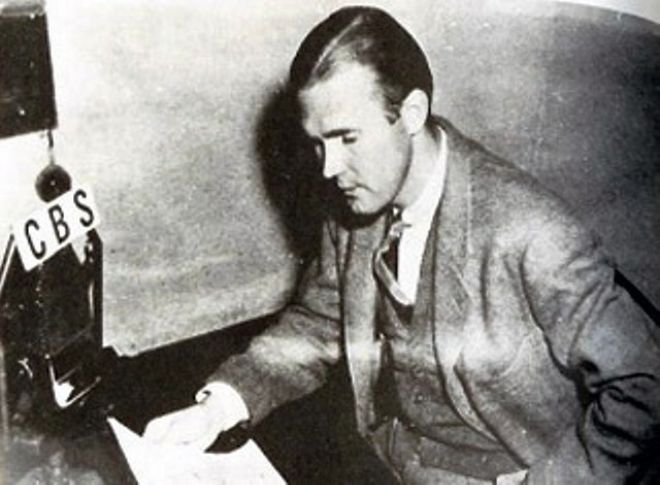

a. 1948-49: WW2 has ended, around the world. However, fighting continues in Greece. The Greek Civil War (1946-1949) was bloody and ferocious. In May 1948, the body of an American journalist was found floating in the bay of Thessaloniki – that of renowned CBS reporter George Polk (journalism’s prestigious Polk Awards are named after him), who had been investigating embezzlement of U.S. aid by the right-wing Greek government. Polk didn’t know how to keep his mouth shut, and during that period of tension, silence was considered a real virtue in Greece. Nobody spoke out loud about the terrible things happening, including the killings of innocent people, blood and corpses in the streets. According to Polk, US dollars of the Marshall plan were travelling abroad hidden in travel bags. They were credited to Greek politicians’ accounts and not used to help the destroyed country.

The Foreign Office didn’t like Polk either. He was messing British political plans in Greece. The timing of the murder was really bad. The country was at civil war, the British and the Americans were trying to increase their political influence in Greece, and the country needed money to make ends meet. The US media was crying out that money was being donated to help Greeks and they in return killed a young American man. State officials demanded that the Greek government find and punish the killer immediately. They came to Greece to supervise the interrogation. The Greek government wanted to close the case and placate their allies, and, in case they didn’t find someone to blame, they could still accuse an innocent.

Grigoris Staktopoulos was a Greek reporter. In my novel his name was changed into Gris – that sounds like the name of Greece and holds the grey scale color of his surname in the Greek language. Gris was walking in the grey zone of history: for some he was a communist, for others an anti-communist; he cooperated with all Greek papers no matter what ideology they carried, in order to earn money to support his family. Although there was no evidence of his guilt, he was an easy target for the government. All the other suspects had somebody to help them. Staktopoulos was alone: he had no powerful friends. His confession was signed after brutal torture.

You never know what will turn on the lights in an author’s mind. What provides the intellectual fuel for writing a novel. I started studying the Polk case – the Staktopoulos case, as I called it, because the great issue for me was how we administer justice in a country that is a toy in the hands of great powers. It could have happened to anybody. You’re waiting for your bus, a policeman says to you “follow me, it’ about a case of yours”, you go to the police station and you return home 12 years later. It could happen to anybody. It could happen to you, it could happen to the person who is sitting next to you. It’s not you who decide. Life does. It’s a matter of historical or geographic timing – maybe a matter of misfortune.

b. 2010-2011 (Greek crisis): a rebellious young high school student is given an assignment for a school project: find the truth. He begins to make a series of discoveries – about history, love, justice, truth, sacrifice and how the past is always with us.

I was really interested in putting together two different ages of Modern Greek history. I wanted to capture the historical adventure of my country. Some things change, because circumstances around us have changed as well. Other things remain hidden and unpunished – they poison everything. Some are carried from one generation to the next. We think that we have left our past behind. Alas, we always find it ahead.

In The Scapegoat major questions arise, while times are changing and one generation passes on the torch to the other: What happens to a country where silence is hereditary, like genetic material? What would have happened, if Greek politicians had more backbone and the great powers less of a tendency to impose their will? What happens if someone avoids the lesser of two evils, but never aims for the best? Does the past teach us lessons? Is passivity in the face of injustice a crime? Why is it so difficult to teach a smart kid?

In his review for The Scapegoat, Theo Leanse commented that “the picture of generations-old moral compromise in a Greece belittled by foreign interest cuts close to the bone”. How is Greece’s difficult past represented and interpreted in contemporary Greek literature? Are there interesting correlations to the present?

Modern Greek History has everything: civil war, innocent blood, foreign power interference, intrigue. That’s why so many Greek novels focus on our historical wounds.

The American title of my novel (The Scapegoat) underlines the connection between the two eras (a now 2010-11 and a then 1948-49). Karen Emmerich says in her Note from the Translator: “In putting the story of Manolis Gris alongside the current crisis in Greece, Nikolaidou implicitly argues that the injustices of the past are still with us, and that scapegoating of all kinds – of political opponents, of immigrants, of the youth who will bear the brunt of the current financial crisis, even of Greece itself within the European Union – pervades the current moment” (p.241).

She couldn’t have said it better. I believe that the parallels between the civil war period in Greece and the current situation in my country are simple: Both then and today basic political decisions are taken somewhere else. It’s a bit like a game of chess or monopoly. Some are playing the game, miles away from Greece, and their moves determine everything in the country. Thus: Are money and influence –that is, everything- at stake? That’s the question.

‘When life takes the lead, literature remains silent […]With cancer I did what I know best: I sat opposite him, looked him in the eyes, put him into words and then moved forward”. How did you decide to turn your fight with cancer into a book? Has this experience turned you into a different person or even a different writer?

The day I was diagnosed with cancer, I remember myself returning home on foot. I was walking on the beach with the results in my hands and a light breeze on my face. I was crying and the tears were drying on my cheeks. And at that moment I found myself thinking: this could become a good book. It may should childish but that thought felt quite comforting. So I started to write So Far So Good. The chronicle of cancer in my breast is a health diary; written in the heat of the moment, day to day. It captures events, thoughts, and feelings from the moment I was diagnosed to the last chemotherapy. In more cinematic terms, I would say that this is my own documentary. A book I wrote with my body. Literally.

As for the disease, of course it changed me. When you have walked through the dark, light can be so glaring and self-fulfilling. When dilemmas come down to yes-no, life-death, you cease to be bothered with trivial things. You get rid of unnecessary burdens. You learn to live for the moment. You make no long-term plans.

And this, I believe, has an impact on words; in the way one perceives and names things. It changes the author’s perspective. Because words may be good and fiction quite entertaining, but what happens when one is in pain? Can words cling on things, name the ineffable and comfort? Can they help us get by in difficulties? In my case they did. And this is no mean feat.

There seems to be a general trend away from fantasy and towards a more realistic approach in literature, with more and more writers incorporating autobiographical elements or testimonies in their books. How is this trend to be explained?

Writers have always incorporated autobiographical elements in their fiction (quite evident in some cases or so disguised in others that they go unnoticed). Since Truman Capote recording reality – either as a narration that incorporates autobiographical elements or as a testimony – has been not just a kind of literary gymnastics but a different way of viewing the world. At times, the pretext “let me tell you a real story” is used, while at others there is the reading bait saying “I have lived this story”. What is certain however is that – whether biographical, autobiographical or historically recorded – an event which is turned into a narration ceases to focus on truth and rather relies on plausibility; and this is what literature has been after since ancient times. After all, memory itself (whether personal, historical or collective) has been a ‘contraption’ that offers meaning to what – often incomprehensible – we experience, hear or see.

‘If parents do not read books, if teachers do not love literature, if most people believe that reading is a luxury activity rather than a human need, why should children think different?’ What is the ‘key’ for young people to turn to literature? What future lies ahead for the ‘traditional’ book in a highly digital era?

Your question is the first question parents usually ask a teacher – the same parents that either for work or for pleasure spend their whole day in front of a computer J. I don’t have all the answers or a magic wand. What I try to do at school – not for repute or out of a learning desire but because of a deep conviction of mine – is to try to show children that reading literature can actually be a gratifying experience. Of course literature stands for many more things: it constitutes the deepest human learning experience. Literature offers us the chance to live not just our own life but a thousand more. It opens up our senses in unexpected ways, while it broadens our perception of the world. For me, things are simple: in case you want more joy in your life or you want to feel and think in the deepest way possible, you incorporate art (not just literature) in your daily life. From the moment you get acquainted with intellectual pleasure, there is no way back. And as you know, when you breathe through art, you don’t age easily. You continue to have that creative mood regardless of age and problems. And this amounts to the greatest gift.

As for technology, you are asking the wrong person: I am a gadget lover. I don’t believe that paper is what is to be saved. The technological revolution is mutatis mutandis of the same (cosmogonic) importance as the revolution of typography. The use of computers and the internet have affected writing and reading in sweeping ways, which is not necessarily bad. Imagine what writing might have meant for the great novelists of the 19th century and the way the use of technology affects the constructive part of literature today in the big hybrid compositions and the narrative montage. We write and read literature in a different way from those writing with pen on paper. I don’t belong to those who are grieving for what is lost. From caves to Facebook, there is a dimension of literature that cannot be lost. It’s what grandmothers use to say “come close, my child, I have a story to tell you”.

How is history taught and written? How can the rise of the far-Right, especially among young people, be explained and fought against? What about the role of the Greek educational system?

History is a narration, so – whether consciously or not – it is written in narrative terms: someone just decides the beginning, the middle and the end; he chooses the protagonists and the events that he wants to incorporate in his narrative plot. Thus what we consider an “objective History” is yet another construction, obeying its respective terms and conditions.

As for the rise of the far-Right, I see it at school, its penetration among young people is quite strong. There is a reason why and it doesn’t just relate to Greece. When the world turns upside down – and we are actually living in turbulent times, when what we regarded as stable and eternal is overturned – the first instinctive reaction is denial: we refuse to acknowledge that there is a new reality, we come together in what we know and we develop an aversion to what is different or unfamiliar. We opt for destruction instead of creation. What is even more dangerous is the discrediting of institutions: “everybody does it, so I’ll do it myself”, “they are all the same”, “there is no salvation, so let’s burn everything down”.

The educational system and the health system are the first victims in times of crisis. Given that I know them quite well – the former as my working environment and the latter due to my treatment for cancer – I am of the opinion that their non-collapse to this moment is due to the self-sacrifice of employees, doctors and teachers. I know it’s easier to just denounce evil: the doctor who is bribed, the teacher who delivers private lessons and is indifferent to his students at school; yet the silent majority is that which keeps schools and hospitals alive at the moment. The educational system – that faceless thing we call educational system – doesn’t refer to school walls and curriculums. It refers to students and teachers. What the school should do is to try to awaken children’s minds. To provide stimuli. To hear what they have to say. To pose questions. I don’t know if it “raises awareness”. What is certain is that students spend half their day at school. Thus, they should be taught not only infinitives and equations, but to discuss what happens around them. To sit before teachers who won’t try to patronize or indoctrinate them into their own beliefs, but who will be in position to provide them with the cognitive tools to help them form their own personality in conditions of freedom. If that’s not a democracy lesson, I don’t know what is.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE