Ersi Sotiropoulos is an acclaimed Greek poet, novelist and short story writer. She studied philosophy and cultural anthropology in Florence and worked with the Greek embassy in Rome. She published her debut novel, The Trick, in 1982. Zigzag through the Bitter Orange Trees [In Greek: Ζιγκ Ζαγκ στις Νεραντζιές] was acclaimed on publication in Greece as “the best novel of the decade” and became the first novel ever to win both the Greek national prize for literature and Greece’s preeminent book critics’ award in 2000. Her novel Eva won the Athens Academy prize for best novel in 2011, and her book of stories Feel blue, dress in red won the National Book Award in 2012.

Her short fiction has appeared in the Literary Review, the Brooklyn Rail, Harvard Review, Circumference, SmokeLong Quarterly, Words Without Borders, Metamorphoses, Absinthe, and Two Lines. She has been a fellow at institutions and universities around the world, including the Rockefeller at Bellagio, Bogliasco Foundation, Sacatar in Brazil, University of Iowa’s International Writing Program, Schloss Wiepersdorf in Germany and Princeton University. Her books have been translated in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Swedish.

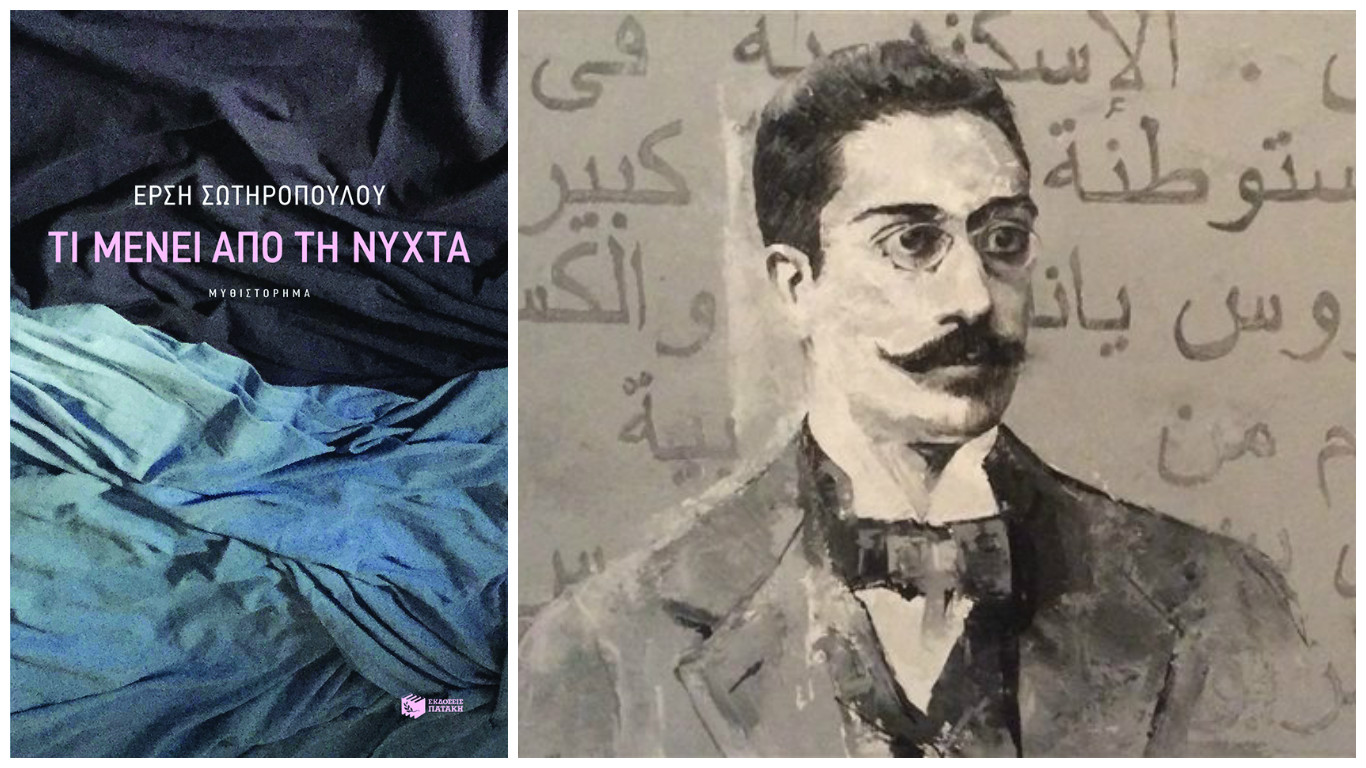

Ersi Sotiropoulos spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest book, which focuses on the Greek poet Cavafy’s stay in Paris, how physical desire may evolve into creative impetus turning a minor romantic poet into a prominent writer, as well as the correlation between art and life noting that “there is a defect behind art and the artist, a complex, a trauma, something missing that enables you to write, to create”. She also comments on how “reading literature can help us distrust clichés and stereotypes, to become aware of the small details that either determine or undermine the vision of the whole”, and how poetry and fiction “help us formulate a conception of the non-existent and (the inevitably) potential”.

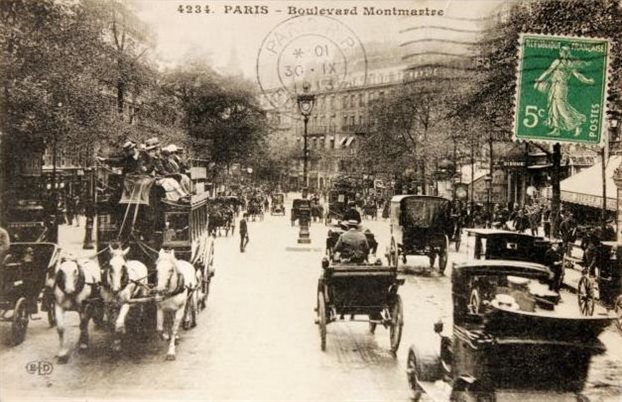

Your latest book – What’s left of the Night– is about Cavafy’s stay in “fin de siècle” Paris. How did you decide to write about one of the less known periods of the poet’s life? Was Paris actually the place where Cavafy was transformed from a minor symbolist and romantic poet into a prominent writer?

It is difficult to dissect and analyze the creative process. I am not the one deciding to write about a specific topic, it’s writing that decides for me. Sometimes it begins with a recurrent image, maybe still blurry, or even a fleeting conversation – like when you haven’t heard something properly but it’s still imprinted in your head – that suddenly comes back. Even when I have to write about something specific, for a commission for instance, the tone will be given somehow outside of the topic, offering that special nuance that will pervade the text, and that’s a process I really enjoy because it gives me the chance to discover new things while writing.

For What’s left of the Night, I was rather driven by questions. There was very little known about Cavafy’s stay in Paris. I was thinking of that young man (whose future course we all know very well), his trip to Paris at a special moment in time, his passion for writing, his anxiety to find his own voice, and how he was tormented by sexual desires forbidden back then. I started to imagine him at that unique crossroads with Alexandria – both old-fashioned and cosmopolitan – in the background, Greece – humiliated and once more destroyed – further away, and finally Paris, illuminated, at the height of its glory. During that process Cavafy turned slowly into a fictional character.

“But we who serve Art/ sometimes with the mind’s intensity/ can create—but of course only for a short time—/pleasure that seems almost physical”, Cavafy wrote in “Half an Hour”. Is this physical desire that permeates Cavafy’s works a driving force in your work as well? What is after all the relationship between art and life?

“Half an Hour” belongs to Cavafy’s hidden poems, the ones that the poet refused to publish during his lifetime; it’s the lyrics of those poems that acted as my lighthouse while I was writing the book. What interested me from the very start was to capture the moment, that exceptional moment when physical desire turns into creative impulse. As for the relationship between art and life, a lot can be said, most of which commonplace. Yet, the fact remains that it is as if there is a defect behind art and the artist, a complex, a trauma, something missing that enables you to write, to create. It might sound a bit simplistic but l truly believe this. Aside from the joy οf creating a whole new world… Lacking something can be a strong trigger. Like love. Reciprocated love quickly fades away; on the other hand, when the object of your desire remains elusive, the flame keeps burning.

Zigzag through the Bitter Orange Trees was acclaimed on publication in Greece as “the best novel of the decade,” while it has been said that what makes your stories memorable is that “at once familiar and troubling, compelling and unapproachable, they give us a new way of seeing”. Can literature free us from the shackles of our certainties about life, revealing other angles under which it is possible to we see the world?

Reading literature can help us distrust clichés and stereotypes, to become aware of the small details that either determine or undermine the vision of the whole. I think that art can change us — the best fiction and poetry do change who we are. They helps us formulate a conception of the non-existent and (the inevitably) potential.

‘To write, I need to distance myself from things … As the years go by, I feel a greater need for silence and isolation …Few are the stimuli that still tantalise me. And they usually come from art, where else?’ Tell us more.

Art is inspired by art, and even more so by life itself. That’s what Cavafy is reflecting on in the novel. I have been reading books since l was very young, and I still have that feeling of sheer pleasure every time I immerse myself in a book I really enjoy, when I listen to a music or see a piece of art that intrigues me. When I write – when people write – inspiration comes from deep inside, like an amalgam of what they have lived and read; a book l once read and think l’ve forgotten may in a subtle way prove much more decisive compared to a more recent or intense personal experience.

In your essay “The view from Greece” you refer to Athens as ‘a collapsing city’. What does that mean? How is what’s happening due to the current socio-economic crisis come into your writing? What has been its effect on cultural and intellectual terms?

I used the expression “collapsing city” not just literally to describe the degraded urban landscape with buildings collapsing, stores closing and the once luminous Olympic installations utterly abandoned. What is also collapsing as a result of the crisis is social cohesion. Despite the important work of social solidarity initiatives, it’s undeniable that poverty and despair are followed by spiritual impoverishment. Arts, the book market, were among the first victims of the crisis. Yet, many young people seem to display a creative energy in recent years. They strive to acquire whatever they can amid the crisis, to leave their own imprint, turning their backs to the anxieties and inhibitions of older generations.

“I grew up reading literature; I became a writer by reading other writers, mostly translated from other languages. […] Without the translators behind those books I would be a different person, completely fucked up. Reading literally saved my life.” What about the new generation of Greek writers? Is there a voice for them in Greece or even abroad?

Not just one voice but many. The first that come into my mind are Ignatis Houvardas and Glykeria Basdeki. Both have written exceptional texts.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE