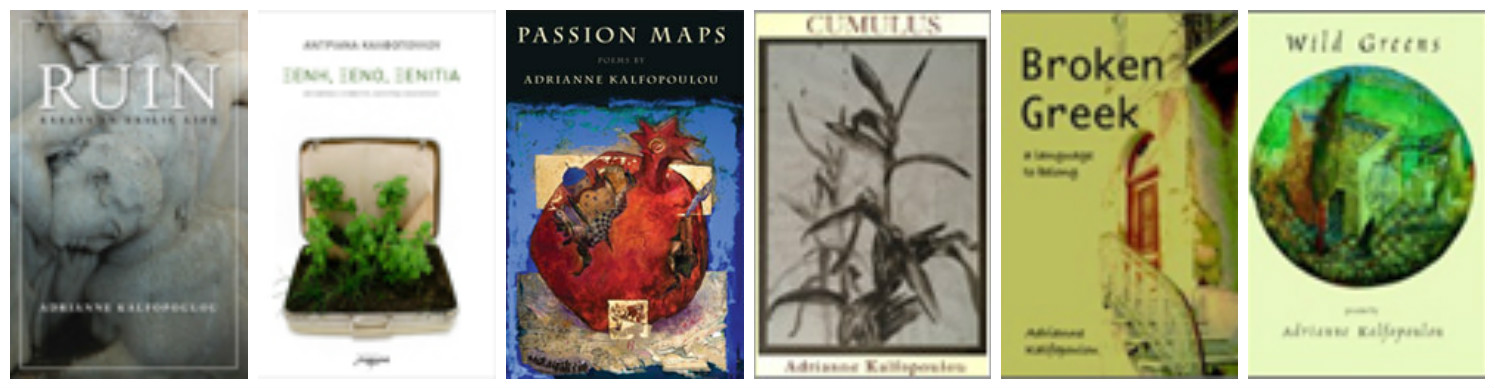

Adrianne Kalfopoulou is a poet, essayist, and scholar. She is the author of three poetry collections, Wild Greens, Cumulus and Passion Maps, a collection of essays Ruin, Essays in Exilic Living and a memoir on place and identity titled Broken Greek, a Language to Belong. Her poems and essays have appeared in Hotel Amerika, Essays & Fictions, Room Magazine, Fogged Clarity, The Broome Street Review and Spoon River Poetry Review. She has been awarded Room magazine’s award in nonfiction, and a Notable Essay of the Year from Best of American Essays 2013. Ξένη, ξένο, ξενιτιά is her first poetry collection in Greek.

She has taught literature and creative writing in various institutions including New York University and the University of Freiburg before joining the full time faculty at DEREE – The American College of Greece as the Writing Program Director. Her scholarly work has focused on 19th and 20th century American literature, particularly the contributions of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, Toni Morrison and Marilynne Robinson. She is currently at work on a monograph that explores Ralph Waldo Emerson’s influence on Sylvia Plath’s poems.

Adrianne Kalfopoulou spoke to Reading Greece* about the different connotations of ’ruin’ and ‘exile’ around which her latest book Ruin: Essays in Exilic Living evolves, and the way the book is indicative of the worldwide shift from a ‘homogenous collectivity’ to a ‘transmigrant subjectivity’. She talks about her ‘conflicted relationship to the language’ commenting that ‘maybe this feeling of remaining in between languages is another way to continue living in a more nuanced, liminal space’.

She characterizes Athens as ‘a traffic jam of historical crossroads’ noting that the city’s layered past is ‘a bit like the rings of Dante’s Inferno, but in reverse; the really hellish moments being above ground’. She comments on the irrational way the current immigrant crisis is dealt with at a European level and concludes that – in the context of ‘shared vulnerabilities’ and ‘mutual dependencies’ –the refugee may act as ‘the example, a testament to the sovereignty of life and the ways we can reconsider our present’.

Ruin: Essays in Exilic Living. Could you elaborate on the role and the different connotations of the words “ruin” and ‘exile” around which your latest book evolves?How would you summarize the conditions you find yourself in and how do they shape your views on sustainability, whether “away” or “at home”?

Since 2014, when Ruin was published, the momentum of the changes in the world has continued to feel overwhelming. I would now describe “ruin” and its resonances in larger terms perhaps, beyond some of the very personal moments that begin many of the essays in the book; for example there is now a refugee dimension to the reality of austerity in Greece, which had been one of the aspects of ruin I explored in the essays. We have a dysfunctional socialist government elected on an anti-austerity vote, which implemented more as opposed to fewer taxes and contributed to more rather than less austerity. I won’t go beyond what’s happening in Greece, but what’s happening here feels emblematic, I believe, of what’s happening in much of the developed world.

One doesn’t assume anymore that government policies are always there for a larger good. So a definition of “exile” or a sense of the “exilic”, would describe a more general feeling of alienation. That is, alienated by the government’s impotence to overcome a current financial impasse one might feel more empathetically identified with the precarities of a refugee. To be suddenly unable to pay property taxes, to be newly unemployed, or without the ability to maintain a lifestyle that might have been taken for granted, makes the fate of the refugee who has lost everything, a closer kin than a northern European who continues to be part of a system that functions and protects basic human needs and rights.

I also think some assumptions of what defines community have become more resilient as a result of the influx of asylum seekers; that is when the complications haven’t given rise to distortions like fascistic nationalisms. I’m with Roberto Balaño who says he empathizes with “people very near to me who understood exile in the way I sometimes understand it myself, which is to say, as life or as an attitude toward life.”Some of the decisions for writing from a very personal point of view in the essays were part of an intention to magnify the fissures in the ordinary, and show the psychic unravelings that take place in small, private ways, as a result of larger political realities. One idea of exile, or the exilic, is that it’s a kind of meta condition, in the literal sense of the Greek, as μετά, after the fact of it all; if we’re to sustain ourselves in the long run I think we need to realize that the rabidity of consumerist economies will increasingly view and treat us as objects for consumption, a commodity like the world itself, as opposed to viewing us as subjects to protect and nourish.

In her review, Joanna Eleftheriou notes that your books are “a refreshing divergence from what Yiorgos Anagnostou has insightfully called a ‘narrative about ethnic socioeconomic success [which] constructs Greek America as a homogeneous collectivity in accordance with the script of American liberal multi-culturalism”. Would you say that your book marks a worldwide shift from a diasporic or immigrant subjectivity to that of transmigrant?

That’s an interesting question, and it touches on various migration narratives; one is that of the returning migrant, like myself who came back to Greece as the fatherland (my father is Greek, and my mother Italian-American), to maybe pick up on a rupture. He left Greece rather clandestinely on the eve of the Civil War because he’d been in the Greek resistance, parts of which were identified with Stalinist Russia at the time. Then there’s the transcultural movements of our day, since travel is just easier and sometimes more feasible for work opportunities, as is currently the case for the very many who’ve migrated at the beginning of the financial crisis, and who continue to move out of the country for work, which I’ve done for short stints as well.

Yiorgos Anagnostou’s idea of a “homogenous collectivity” as a Greek-American construction of assimilation seems part of what early and mid 20th century migrations to the U.S. were all about, a need to invent identities in keeping with a new world order (so to speak), and simultaneously to maintain a collective, even a defensive, sense of origin. I think much of that has changed because that sense of origin, as a concept, is too essentialist for the hybridities that make up our contemporary world, and also the speed with which our realities can change given the constant and multiple influences in our lives.

At the squat where I go with other volunteers to do activities with some of the children, Afghan and Syrian families, who would probably not mix under other circumstances, are sharing living spaces. As the building was once a school, the classrooms are where multiple families live, their living areas separated by a curtain or sheet; the Afghan families and Syrian families live on separate floors, but apart from that they share bathrooms, food, the playground area. I’ve noticed women starting to wear trousers and tights and sweat pants, and they didn’t when they first arrived, it was only long skirts. The kids were enjoying nail polish one morning when one of the volunteers brought a nail kit. She was from Chicago, and said she wanted to spend a few days at the squat and that was the easiest thing for her to bring. It started a wave of requests. One morning a father was sitting on his own and his 6 year old daughter was feeling impatient about waiting for her turn, so he took one of the bottles of nail polish and painted her nails for her, then his young son was envious, and wanted his nails colored also and the father laughed. I don’t expect this a scene that would have taken place in an Afghan village. It’s a small thing, very small, but indicative of how people will change given a changed environment.

You have stated that eros may actually act as an antidote in times of trauma and/or political upheaval. Does eros also act as a source of inspiration in your poetry?

Oh Yes, but to quote Sappho, the inspiration is often γλυκύπικρον, sweet bitter. As Anne Carson notes the “sweetbitter” of eros is a confluence and a paradox. She also quotes Anakreon in Eros, the Bittersweet, who describes erotic desire as a “sweet fire” – I think it’s the ultimate exilic state! One is brought very close to oneself while, also, suddenly estranged in a continuous reaching toward an(other) – wherever and whomever that might be. It’s a crisis of contour as much as recognition, boundaries are suddenly shifted, which is what happens when we’re displaced. This brings on the confusions too, in oneself to begin with, but it’s also where opportunities, or new ways of being, are seeded. It would indeed be an antidote, if in a spirit of eros the overture to the other could make of strangeness something more hospitable, isn’t that the whole point of φιλοξενία, of being hospitable to the stranger or foreigner, including our estranged selves.

In her review of your first collection of poetry written in Greek [Ξένη, ξένο, ξενιτιά] Maria Topali notes that your poetry “is woven by the absence of a mother tongue (given that you write in English) and warped in the foreign/father land (given that you have chosen to live in Greece)“. How would you comment on that?

Well, this is a good example of one of my estrangements, my conflicted relationship to the language, and it’s been the subject of many therapy sessions! My father left Greece basically on the run, and as far as he was concerned he was most likely not coming back. He also changed his last name to “Calfo” from “Kalfopoulos”, which like others of that generation was indicative of their rejection of the past. So my return to the country both shocked and, perhaps, if reluctantly, gave him a quiet pride that I wished to embrace something of his. But we rarely spoke Greek at home and he is not religious so we were not associated with any Greek Orthodox Church while we lived in the U.S. or South East Asia (where I was born). On some level Greek remained the unspoken language of Julia Kristeva’s semiotic, which is ironic since yes this is my father’s tongue, but his motherland.

In discussions I’ve had with the Greek poet Katerina Iliopoulou, who did the translations in conversation with me for Ξένη, ξένο, ξενιτιά, we’ve often mentioned the sensation of otherness that translation invites. There’s a trickster quality to being able to simultaneously access the language, its vernacular and contexts of expression, while remaining on the outside of it, as someone who never learned the language formally. Being a brilliant grammarian of the language doesn’t necessarily mean you are using the language correctly or have understood its nuances. There’s a small moment in Edmund Keeley’s and Phillip Sherrard’s translation of Seferis’ ΑΡΝΗΣΗ or “Denial” where“ο μπάτης” is translated as “sea-breeze”, which isn’t incorrect but we’ve lost the sense of it being a term specific to fishermen and seamen familiar with the sea. Recently I made an attempt at translating some recent Kiki Dimoula’s poems, trying to translate not just the language, but her contexts, into English, was thrilling. I’m now writing something that involves an American who learns single Greek words and phrases gradually as she accesses experiences she can’t articulate in English. So maybe this feeing of remaining in between languages is another way to continue living in a more nuanced, liminal space.

“Athens can look like a traffic jam of historical crossroads with those going in different directions demanding their right of way”. Tell us more.

This makes me laugh, but yes, a jam indeed. I had a completely visual image of this when I was thinking of how I would describe contemporary Athens; I thought of cars stopped at a crossroads, as someone pushing one of those carts full of metal scraps is blocking the flow; carts generally used by Pakistani and African immigrants for collecting paper and metal that can be sold from the trash. So while Athens has the traffic lights and roads it is part of a fabric of other economies and lifestyles that adds to its cosmopolitanism. It’s never static and it’s nearly impossible to describe simply. Maybe in a world where major cities are being bought up by multinationals, like Times Square and parts of London, where the idea of public space is rarely public anymore, Athens is still a city that makes room for its complexity and tensions.

Maybe it’s one of the last real cities in its gritty inclusiveness, its graffiti-smothered walls, and noisy traffic, unlike the cities of the north, and certainly unlike a city like New York, there is an unregimented, anarchic quality to it, but something tender too. And then there’s its palimpsest of history, the way one seems to go down into the layers of antiquity just by entering a metro station where archeological findings from digging to build a metro has unearthed the city’s layered past, a bit like the rings of Dante’s Inferno, but in reverse; the really hellish moments being above ground.

“To be a refugee means the refuge of what once provided the rituals of stability, like home and shelter, no longer exist, that larger threats than those of the risks of being a refugee are being fled”. What about the way the immigrant crisis has been dealt with both at a national and European level?

Oh dear, whatever I say is going to either sound like I’m preaching to the choir or on the verge of an attack of hysteria. The ways this issue has been addressed on the level European governments and European policy seems irrational at best. I mean why did the EU decide to give Turkey money (3 billion euros) to deal with the crisis when a) Turkey is not a part of the EU, and b) Greece is the border country, or peninsula with the 45 thousand asylum seekers. There’s also c) the obvious fact of Greece’s economic difficulties. It’s hard not to read these measures as a (yet another) punishing gesture because (yet again) Greece somehow didn’t learn the lesson of obedience. That is, we “allowed” so many refugees into the country who were trying to make their way into northern Europe before the borders closed.

My cynical reading is that since Turkey is not a part of the EU these asylum seekers are not under the jurisdictions of European law and have no claim to human rights under European law as long as they are not in a European country. One thing though this might be an opportunity for Greece as it finds itself in this space of confluences. Some of my most rewarding moments in the midst of what’s been a very difficult time, has been the time spent with refugee families, the children and young adults in particular; these are people caught in their own moments of history who have found themselves here and may be part of what will give Greece, and Europe, revitalized and new perspectives. The danger, and it is a clear danger, is in the kinds of reactive policies and attitudes of countries like Hungry, or Denmark (and Switzerland, too), whose policies have reinforced discriminatory and racist attitudes; for example, some have passed laws to confiscate assets of asylum seekers.

It’s always easy to offer something when you have the advantage. I call it the missionary gesture, and I’m not undermining the importance of those contributions, but I’m more interested in shared vulnerabilities, in recognizing mutual dependencies. Hannah Arendt quotes René Char who says “Notre heritage n’est précédé d’aucun testatment” (our inheritance, or heritage, isn’t guaranteed by, or preceded by, any testament); she means this to be liberating, “one of the great advantages of our time…” that we take from our pasts what in fact helps us. Again I think of the refugee as the example, a testament to the sovereignty of life and the ways we can reconsider our present.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE