Theodoros Chiotis is a poet and literary theorist. His work has appeared in print and online magazines and anthologies in Greece, the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Turkey, Poland and Croatia, amongst others. He is the editor and translator of the anthology Futures: Poetry of the Greek Crisis (Penned in the Margins, 2015). He has translated contemporary British and American poets into Greek and Aristophanes into English. He has published critical work on contemporary poetry, digital literature and autobiographical discourse in academic volumes in Greece and the UK.

He is a member of the editorial board of the Greek literary magazine [φρμκ], contributing editor for Hotel magazine, contributes Rhizosome, an ongoing narrative to the aglimpseof platform and has acted as associate editor for Litmus. He has been invited to read and perform his work in festivals both in Greece and abroad. His project Mutualised Archives, an ongoing performative interdisciplinary work unfolding throughout the whole of 2017, recently received the Dot Award by the Institute for the Institute for the Future of the Book and Bournemouth University. He is the Project Manager of the Cavafy Archive (Onassis Foundation). Screen, a collaborative book with London-based photographer Nikolas Ventourakis, is coming out from Paper Tigers Books in April 2017 with more projects coming out later in the year.

Theodoros Chiotis spoke to Reading Greece* about Futures: Poetry of the Greek Crisis noting that “the poets included in the book belong to, for lack of a better term, a ‘younger’ generation of poets writing, overtly or covertly, about how a significant political and fiscal upheaval impacts on society” and that “there was a very conscious decision to investigate how this experience of uncertainty and precarity carries across language and cultures”. Asked about his decision to use financial terms as titles in all of the anthology’s sections, he comments that “it felt important that poetry would approach these terms cribbed by economists from very different backgrounds and reclaim them”.

As for the current generation of Greek poets, he explains that it is “a generation that had to negotiate with their relationship with modernism and postmodernism, identity politics and notions of national and ethnic authenticity”, “a generation of multitudes”, “often challenging the concept of cultural and national boundaries on a micro and a macro level”. He concludes that “this particular historical circumstance might be a once-in-a-generation opportunity for contemporary Greek literature to be diffused outside Greece”, which means that all interested parties should “rethink the cultural, social and political implications of the translation of contemporary Greek poetry and what it might ferry across languages and cultures”.

How did the idea of Futures come up? On which criteria was the selection of the poets included in the anthology based?

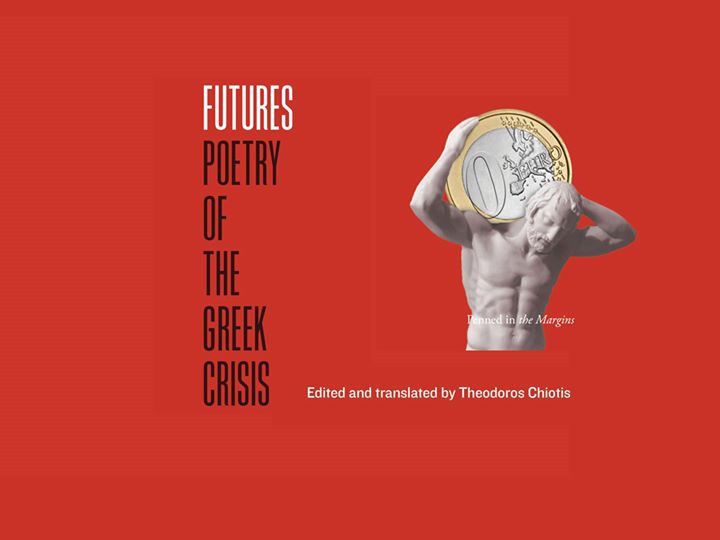

Τhe anthology gestated over the period of two years. The initial seeds of the book were sown in October 2012; a two-and-a-half-year period of research and translation followed with the eventual publication of the book in November 2015. It is fair to say that the final selection of poets included in the book was dictated by a variety of factors; primarily, the poems included in the anthology tackle, engage and experiment with Greek and non-Greek poetic tradition in ways unforeseen up until now. The poets included in the book belong to, for lack of a better term, a “younger” generation of poets writing, overtly or covertly, about how a significant political and fiscal upheaval impacts on society. It was fascinating to see how this societal transition into uncertainty and precarity is reflected on both a political (personal and collective) and literary context and how these poets reflect on and mine this situation for material; furthermore, there was a very conscious decision to investigate how this experience of uncertainty and precarity carries across language and cultures.

Hence, I decided to also include poems written by poets who might not be native Greeks or second generation Greeks but have some other sort of connection with Greece. It was very important for me to explore the boundaries between languages and concepts of personal and collective identity and how these are affected and altered in times of crisis. The poets included in the anthology all experiment in fascinating, often provocative, ways with these very ideas. The anthology is a snapshot of a specific point in contemporary Greek poetic production. I am very satisfied with the selection of poets and poems included in the anthology but I certainly have regrets about the poems and poets that were left out for reasons that were purely practical. Unfortunately, a printed book is a finite product by its very definition.

Both the title of the anthology and the section titles “reflect the vocabulary of a supposedly bloodless fiscal war”, to use Adrianne Kalfopoulou’s words, while ‘Futures’ as a title is “slyly hopeful in this irony”. How did you choose these titles? And to what end?

The anthology is divided in five sections all of which derive from financial terms (Assessment, Adjustment, Implementation, Singularity, Acceleration). When researching the book, I found it fascinating how these very technical, abstract terms cribbed from a variety of disciplines have seeped into everyday language and have change how we perceive and think about certain things. I was thus very interested in seeing how one can reclaim language and how poetry can help us do that.

It also needs saying that the poems included in Futures: Poetry of the Greek Crisis form an oblique narrative laid out in the book by the use of financial terms. The fiscal and attendant social and political crisis tends to simplify and impoverish our discourse about current events. It felt important that poetry would approach these terms cribbed by economists from very different backgrounds and reclaim them; it felt not only timely but also necessary to try and reconsider how complex the quotidian really is at times like these.

How do you respond to those that talk about a “Greek poetry of the crisis” and “a new generation of Greek poets” that in a way resembles the generation of the 1930s?

I am wary of comparisons in general, if only because comparisons tend to flatten out complexity and circumstance. I would refrain from comparing any generation, including this one, with the generation of the 1930s which was a very heterogeneous group of poets and writers in its own right. The historical significance of the generation of the 1930s and its relevance to current poetic production is not only addressed but also recalibrated in certain poems included in Futures; the generation of the 1930s is certainly part of the poetic makeup of the current “generation” (again, a term I feel that is inadequate at this point) but it is also fair to say that the poets writing at the moment are also engaging with the interwar poets, the generation of the 1970s but also with non-Greek, non-Western poetic traditions that the generation of the 1930s did not.

On top of this, this is a generation of poets that had to negotiate with their relationship with modernism and postmodernism, identity politics and notions of national and ethnic authenticity. This is a generation of poets proficient in many languages, a generation which has lived (or still lives) outside Greece and carries with it strains and traces of this life experience; this is a generation of multitudes, a generation born in the diaspora or forced into becoming diasporic; this is a generation which engages and dabbles in many different art forms (music, painting, performance art, amongst others), and converses with its fellow non-Greek poets on an equal footing not only in person at various international poetry festivals and workshops but also in their work, often challenging the concept of cultural and national boundaries on a micro and a macro level.

The advancement of communication technologies has certainly altered the cultural landscape of the poets writing at the moment in ways that the generation of the 1930s could not have envisioned or experience. It is therefore very important to move beyond such binaries and comparisons and acknowledge the sheer complexity and richness of the work produced by the current crop of poets. We need to contextualise the current poetic production not in relation to what has gone before but what is happening in the present on a broader, transnational scale. Otherwise, we are doing the poets and ourselves, as readers, a great disservice.

As Vassilis Lambropoulos notes “of all the arts, poetry has been identified as the most representative of the current national crisis. It constitutes the major cultural domain where the Greek emergency and/or exception are being negotiated”. Does poetry constitute a way to talk about the present? To what extent can it be used to debunk stereotypes related to our ancestry, our national identity and our glorious but long gone past?

Vasilis Lambropoulos’ comment is acute in its observation and I agree with it; indeed, poetry seems to have made a significant comeback but I feel that we also need to go back to thinking poetry and art in general not as means of self-expression (which I have many problems with both as a concept and a modus operandi of art) but more significantly as a toolbox. Poetry can be seen as a toolbox which one sees the world with, a toolbox one can use to understand without simplifying the complexities of the current state of the world. Poetry is an opportunity to organise and rethink how consciousness works and how it is organised and how it might work.

In these times, poetry can be a way of thinking about the new parameters of our everyday life: poetry can circumscribe, narrate and navigate the New Normal, no matter how terrifying it seems. Poetry will help us understand what is this New Normal we find ourselves living in. The current narrative about contemporary Greek poetry rightly emphasises the velocity of its response to public events and their impact on a personal and a collective level. The poems written now chart and map a rapidly changing world where poetic style and intent literally conjure personal and communal identities which are multiple, hybrid and radically other. The poems written now often force us into acknowledging long received notions of ancestry and identity as non-linear ideological constructs in need of reassessment, reframing and reshaping.

In the field of literature and especially poetry, translations of younger poets are scattered. Has the crisis ignited the interest of foreign readers for Greek literature?

It is probably fair to say that the interest of foreign readers for Greek literature has been ignited by the crisis but we should be very vigilant about this renewed interest and in what ways it might be appropriated. This is a very crucial moment for contemporary Greek literature regarding its potential promotion to a non-Greek speaking audience; in fact, this particular historical circumstance might be a once-in-a-generation opportunity for contemporary Greek literature to be diffused outside Greece. Of course, this means that translators working on contemporary Greek literature are not just mediators across languages and cultures but also ambassadors of contemporary Greek literature.

It is therefore very important for all interested parties to rethink the cultural, social and political implications of the translation of contemporary Greek poetry and what it might ferry across languages and cultures. Translation might carry its own voltage but it is both a gesture and a practice of cultural openness and hospitality. And as such, its sustainable growth and evolution needs to be supported and nurtured first and foremost by a consistent state cultural policy.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

©INTRO IMAGE: Stavros Petropoulos

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE