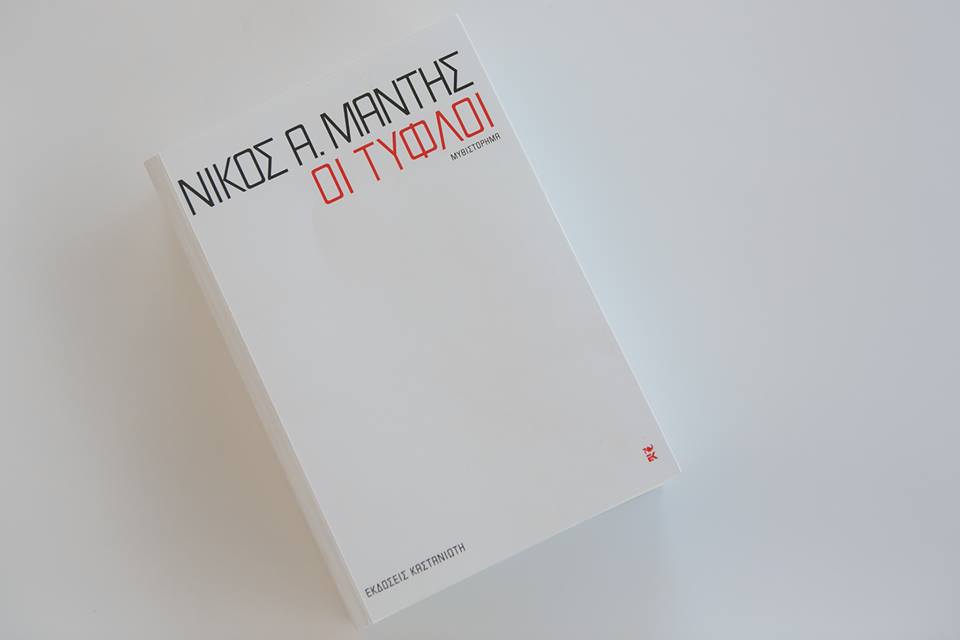

Nikos Mandis is the author of four novels, one book of stories and three poetry collections. He is also a translator of English language fiction. He lives and works in Athens. His latest novel is called The Blind Ones and has just come out.

Nikos Mandis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest novel The Blind Ones, noting that his main goal was “to create a somewhat complex mix of interwoven stories, that would have Athens as the main protagonist, but also Greece as a whole, mingling versions from its current and older self, using the mythological archetype of the labyrinth and the Minotaur as a blueprint”.

He also comments on how violence, in its multiple connotations and manifestations, is dealt with in his books, as well as on how his language has evolved or become differentiated from one book to the next. He characterizes international acclaim as “a perpetually elusive goal for Greek writers”, and concludes that a problem in some parts of Greek fiction is that “traditionally, writers tended to use it not as a goal, as a way to enjoy storytelling per se, but as a means, as part of a wider agenda, be it political, national, social, etc. I think what we need are some really crazy and bold ‘servants of fiction’, writers whose true loyalty will be towards great stories and nothing else”.

Your latest novel The Blind Ones was just published and has already received rave reviews. Tell us a few things about the book.

It is a book of about 600 pages, with a lot of characters, plots and subplots, most of which revolve around the centre of Athens within a time span that goes from the current era back to the 1970s (the time of the junta) and back again, and also some seemingly random scenes that work as intermissions and take us as far as ancient Greece or even prehistoric Babylon. The central story, however, is about the quest of the main character (Isidoros) to find the girl he loves and has lost (Sophia) in the backstreets of downtown Athens, during a time of particular turmoil and unrest (the summer of 2011).

In his review, Vangelis Hatzivasileiou notes that The Blind Ones is not just a political novel but a plunge into modern Greek political identity. How is the social interwoven with the existential in the book?

Well, I’m not sure I can answer that. I certainly wanted the book to transcend well-known categorizations such as ‘political novel’ or worse ‘Greek crisis novel’, as well as the more fashionable one of ‘postmodern novel’. My main goal was to create a somewhat complex mix of interwoven stories, that would have Athens as the main protagonist, but also Greece as a whole, mingling versions from its current and older self, using the mythological archetype of the labyrinth and the Minotaur as a blueprint. I also wanted to write a thriller that would combine elements of modern paranoia, especially the local brand of conspiracy theories and their political underpins, that I came to be fascinated with.

“I have always wanted to write a multi-layered novel, a story that would connect multiple persons and different readings of reality, which would however be centered in Athens…I had the feeling that the way Athens was depicted in the books was more or less incidental…I wanted the city to come to the fore through its history, unveiling the multiple levels that constitute its identity”. Tell us more.

Yeah, as I said earlier, that was what I had in mind. I always loved the way cities of the world became literary cities and were eternally mythologized in the works of great writers, be it Hugo’s Paris, Dickens’ London, Durrell’s Alexandria, Sabato’s Buenos Aires, Mahfouz’s Cairo, Auster’s New York, Pamuk’s Istanbul, the list is endless. I had the vain ambition that I could do something similar with Athens, as a kind of work-in-progress to mythologize the Greek main city, which, the way I saw it, did not have a similar literary treatment, at least its modern embodiment.

It has been argued that violence is the opium of the era. How is violence, in its multiple connotations and manifestations, dealt with in your books?

Violence -especially in its more understated, ‘muted’ version- is a great means for creating tension in fiction, so I really go for it, hoping to use it wisely and with restraint. On the other hand, in our everyday, ‘real’ lives, violence is something we tend to encounter and even suffer more and more often, either in the context of world news, or in the daily life of a crisis-stricken country. Moreover, violence can be also politicized, seen by various agents as a currency and a means for desired change. All these are recurring elements that one should take note of when writing fiction about Greece today, within a social environment that frequently asks writers to ‘take sides’ in an ongoing conflict, be it class struggle, or the need to modernize the country, depending on one’s ideological viewpoint. I tried to stay out of it, being aware, of course, that trying to stay out is also very political.

What about language? How has your language evolved or become differentiated since your first writings?

I think the use of language in my fiction tends to gravitate towards each book’s scope in terms of storytelling, so sometimes it is exceedingly lyrical (as in my first novel, Winter Snow) and sometimes quite sparse (as in my previous novel, Rock, Paper, Scissors). In this one, language tried to imitate the book’s structure, therefore it revolved around seemingly endless phrases, sentences and paragraphs, testing the reader’s patience, towards what -I hope- can be seen as a kind of esthetic reward and not total exasperation. I felt that if I was dealing with something ‘labyrinthine’, the novel’s language somehow had to follow suit.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

I think that this is a total fallacy, a notion that has next to zero credibility and truth. Short form is a very complex and demanding sort of prose writing, and it has produced excellent works in Greek literature, but the same can be said about novels, from Roidis to the world-renowned Kazantzakis, to Vassilikos and Tsirkas. I believe it is nonsensical to say that one sort of writing is more inherently ‘Greek’ compared to others and also quite defeatist to be honest.

“I consider that the novel is one of the means that will enable Greece to enter a broader map and communicate with people beyond its borders”. Does the new generation of Greek writes have the potential to attract foreign readers?

International acclaim seems to be a perpetually elusive goal for Greek writers. Frankly, I don’t have a fixed answer for that, i.e. whether it is a matter of sheer quality (or lack thereof) or of a more complex nature, like the limited use of the Greek language globally, the absence of a state-funded translations program, etc. I think that, if I had to pin down a problem in some parts of Greek fiction, it would be that, traditionally, writers tended to use it not as a goal, as a way to enjoy storytelling per se, but as a means, as part of a wider agenda, be it political, national, social, etc. I think what we need are some really crazy and bold ‘servants of fiction’, writers whose true loyalty will be towards great stories and nothing else.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE