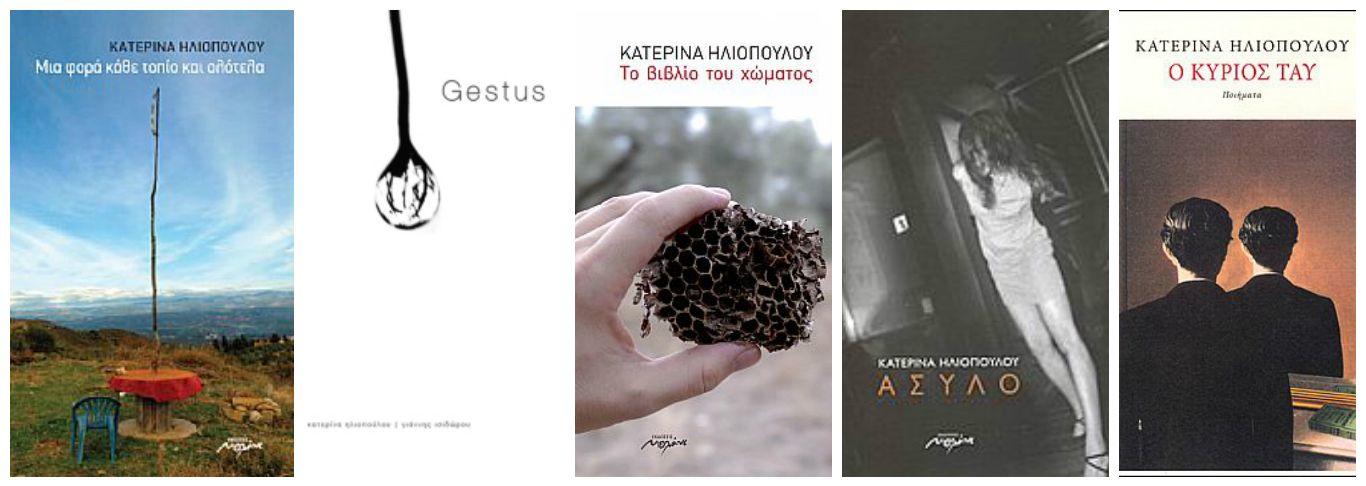

Katerina Iliopoulou is a poet, artist and translator, who lives and works in Athens. Her poetry books are Mister T., 2007 (first prize for a new author by the literary journal Diavazo), Asylum (2008), The Book of the soil (2011) Gestus, (poetry and photography, [frmk], 2014, with Yiannis Isidorou), Every place only once, and completely (2015), all published by Melani editions. She is also the author of several essays and reviews on poetry. Her translations into Greek include the work of Sylvia Plath (Ariel, the restored edition, Melani 2012), Mina Loy, Robert Hass, Ted Hughes, Walt Whitman.

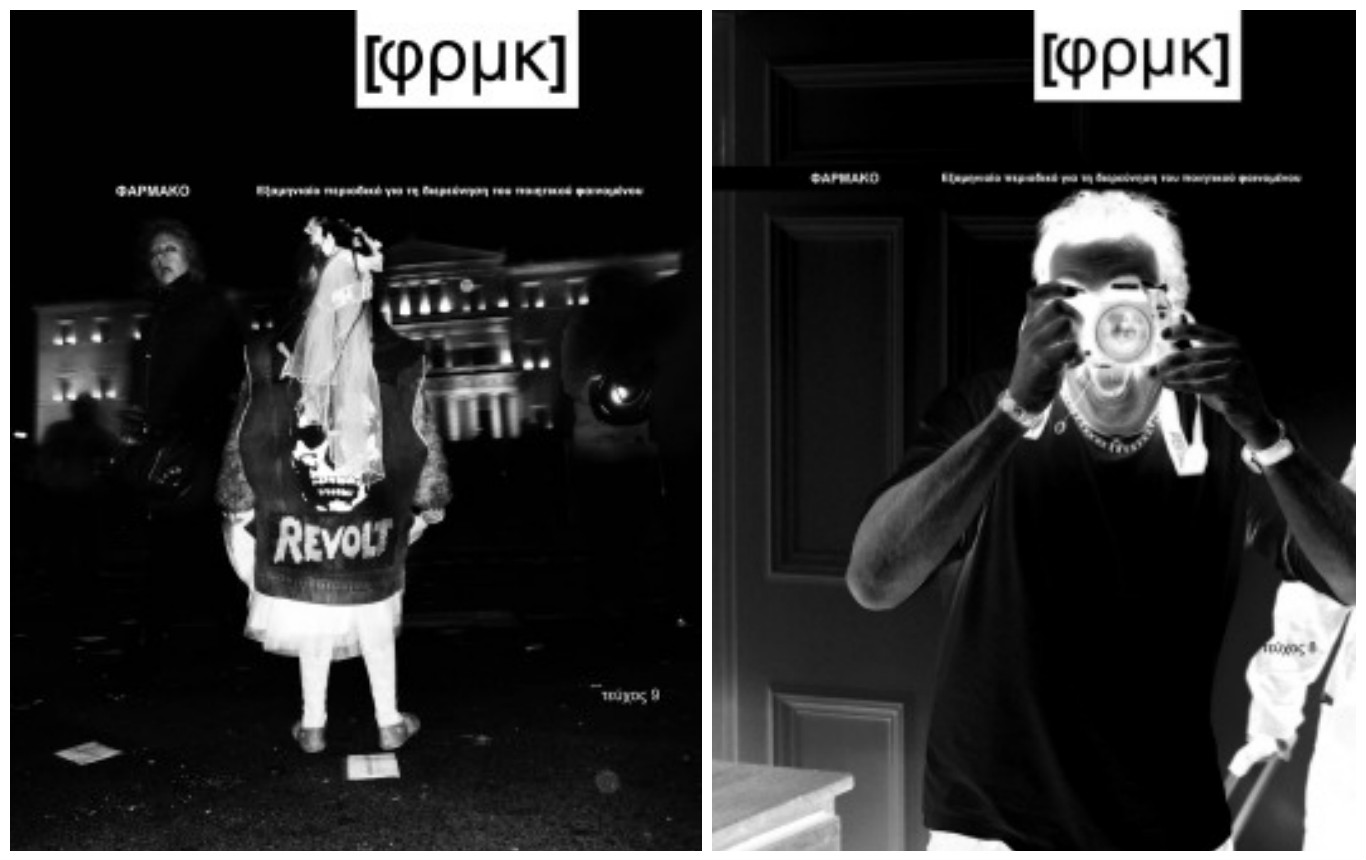

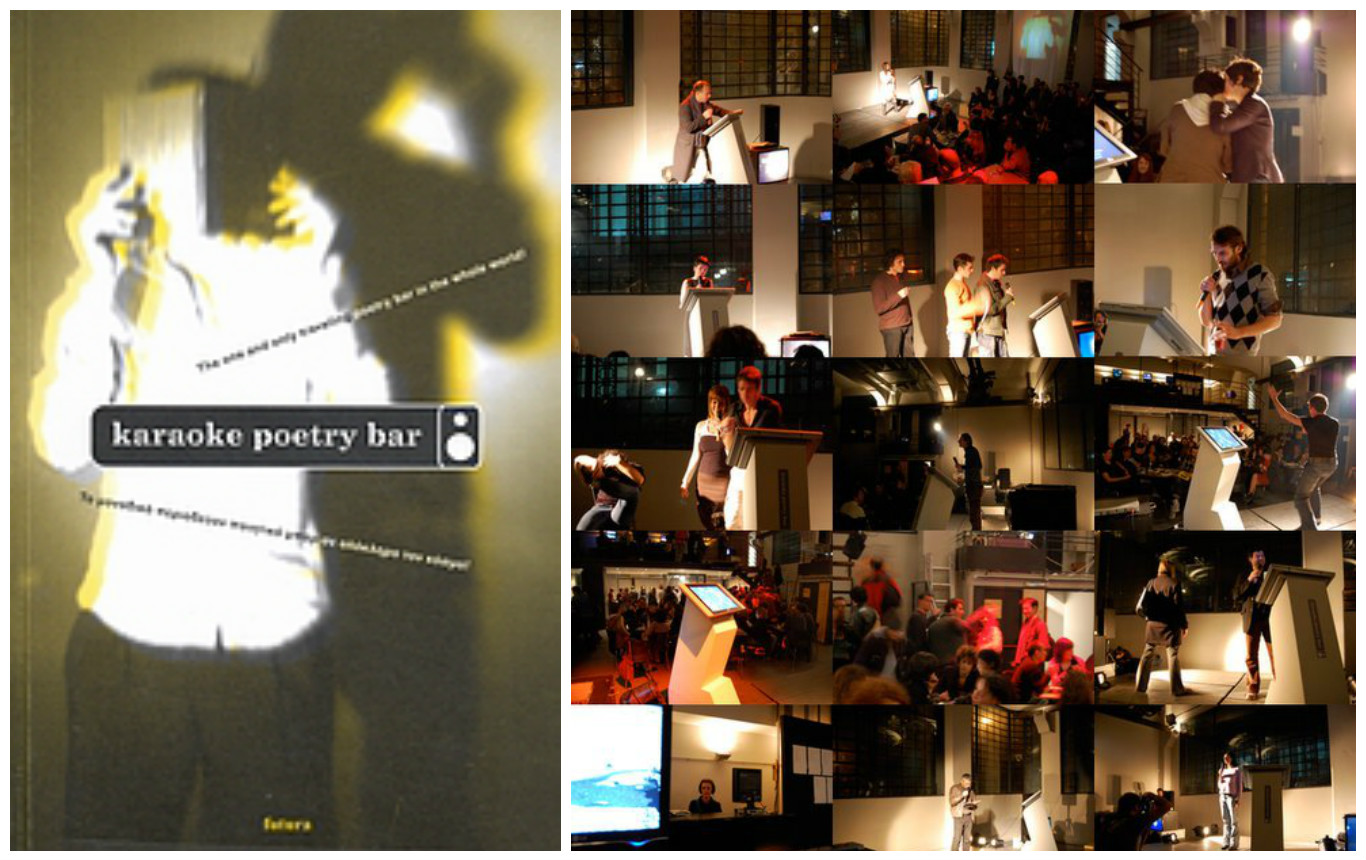

Her poetry has been translated and published in literary reviews, journals and anthologies in many languages (English, French, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Finnish, Turkish, Bulgarian) and she has participated in a number of international writing and translation programs, festivals and biennials. She is the editor of a bilingual anthology of contemporary Greek poetry (Karaoke Poetry Bar, 2007) and co-editor of greekpoetrynow.com. She is editor in chief of FRMK, (pharmako) a biannual journal on poetry, poetics and visual arts.

Katerina Iliopoulou spoke to Reading Greece* about what changed and what remained the same in her poetry over the years, noting that she often imagines her books “as installations, as having a life outside the written text, ideally becoming book-houses or landscape-books that can be read, inhabited and crossed”. She also comments on how the notion of space/place is imprinted on her writings, explaining that “the idea of space in my poetry relates to the question who am I?, it is a kind of ontology, if I may say so, which moves away from metaphysics and touches the material world in order to research and re-invent”.

She argues that “poetry is an active way to observe and feel the world which is perpetually incomplete, immense, contradictory, full of meanings and full of collapses”, and concludes that “we have to find new ways to talk about influences, beyond national, linear or historical connections. The work of art is a kind of passage and because of it we are able to pass through borders, genres, constructions, deconstructions and transformations”.

From Mister T. in 2007 to Every place only once, and completely in 2015. What has changed and what has remained the same in your poetry?

My first book Mister T. is a book of apprenticeship in which the main character Mister T. became both my creation and my guide to poetry. In a way he taught me how to be the poet I wanted to be. What we call inspiration is the power that draws you to something which is attempting to talk to you. It is a meeting. To find the language to conduct this meeting is the adventure of art. So every one of my books is a different country, so to speak and a different field of research. Poetry for me is a way to think, know and connect, it is like creating a mystery instead of solving it and somehow this mystery is also the answer. I often imagine my books as installations, as having a life outside the written text, ideally becoming book-houses or landscape-books that can be read, inhabited and crossed. Something you could experience with your whole body. The element of composition is very important to me, part instinct, part artistic decision. In my books there are autonomous poems, or specific sections which are connected through a narrative or conceptual stream. The composition is revealed to the reader by reading the book in a linear way from beginning to end, discovering the connections, the references and relationships between the texts.

“Not who I am but where I am”. How is the notion of space/place, in all its connotations, present in your writings?

I think that the idea of space in my poetry relates to the question who am I?, it is a kind of ontology, if I may say so, which moves away from metaphysics and touches the material world in order to research and re-invent. We are inside place and place is within us. It gives birth to us and we give birth to it, it dreams of us and we dream of it and so it remains always new, insofar as we are able to develop with it a dialectical relationship insofar as we discover it and simultaneously discover ourselves. The book of the soil, my third book, proposes poetry as a strategy for life. It is formulated around the idea that the world we live in is not a completed work, nor a landscape to be looked at, but a field of action. The book questions the nature of reality and imagination, wonders about the gaze which thinks and the senses which seek the non-existent. There are two characters in the book, a man and a woman: they read the landscape as if it were a text and at the same time they write it. They observe and inhabit it with their thoughts, their senses, their imagination and their memory.

In my last book, Every place only once, and completely, I tried to poetically conceive the idea of homeland, as mnemonic, historical, sensual, individual but also collective place and also as illusion, invention, memory, desire. The book is a journey in the heart of the country, which remains conspicuous, undefined, inconceivable. But here the journey, as passage (poros) and questioning (aporia), is not a destination but unraveling. And the place is nothing but the field of reception of a palimpsest of inscriptions and interpretations, without coinciding with any of them. It became clear to me in the process of writing the book that it would be impossible to deal with this subject if I myself as a writer was not prepared to be lost, did not risk to allow multiplicity or even vertigo to happen. Including narrative and poetic essay, lyrical poetry and autobiography and incorporating texts from other writers, Every place only once, and completely, is an archaeology of the present which uses different means in order to approach a center that remains uninhabited, a desire which is constantly moving fleetingly.

You are editor in chief of FRΜΚ, a literary magazine aiming to explore the poetic phenomenon in its entirety. What differentiates FRMK from similar ventures?

FRMK (pharmako) is a collective work. This collective between the poets who consist its editorial group was formed over time, through numerous common projects in the last decade and shared concerns, but mainly an intrinsic interest or passion for poetry matters beyond each one’s personal work. The magazine was created because of the need to establish a place where this dialogue could continue and become public. The discussion between the editors group, on matters of contemporary poetics and the relation between poetry and society, that we have been publishing in FRMK for the past 5 issues (more than two years), soon to become a book, is an important part of our activities. We tried to create a magazine that would not be a catalog of texts but a field for meeting, dialogue and research. FRMK aspires to bring forward specific aspects of contemporary Greek poetry and thus form a distinctive character, trying to detect and articulate some criteria of what is and what an active contemporary poetry can be. Extensive translations and presentations of the work of important poets from many different languages (mainly from the 1950s and forward), often for the first time in Greek, and the presence of theory with texts from important thinkers and philosophers form the main body of the magazine, while we have already created a corpus of book reviews for some of the most interesting poetry books written in the past four years. The ways that poetry participates and relates to other arts and the presentation of six Greek visual artists in each issue through a sixteen page art section, alongside the overall design of the magazine complement its course so far.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

I am a bit skeptical concerning this trend and it is a complex phenomenon. I don’t know what it means. What I do know is that there are powerful poetry voices in Greece who have emerged the past 15 years, some of them the recent years, and I think it is urgent to discuss, study and bring forward these voices. The poetry books by these poets create language which is a provocation and an invitation for critical thinking and self reflection. If we fail, as poets, philologists, critics, historians, readers, (and there is an incredible lack of serious and consistent criticism, or studying of the new Greek poetry) to recognize and acknowledge these signs, we will have lost the opportunity to know the art of our time and only observe the spectacle.

Poetry is an active way to observe and feel the world which is perpetually incomplete, immense, contradictory, full of meanings and full of collapses. In poetry, language is disrupted, is dislocated and this maybe brings forward the possibility for us to deny the world as it is. It seems nowadays that our world is described through a unique narrative, that is: economics. But we cannot accept our lives to be reduced in numbers. We need alternative narratives in order to live because if we accept our lives to be nothing but a useful juxtaposition of numbers we are ready to accept abyssal horror once again. Poetry is an alternative narrative of crucial importance. It deals with all the complex matters of humanity in its own poetic way, a way always of doubting and searching, which includes the body and its uprise, defends what is real and the uniqueness of the experience of every human being in a world dominated by the totalitarianism of commodities. By creating new metaphors, new vehicles of meaning, it regenerates our spirit, helps us develop critical thinking, describe ourselves, interpret our lives with more complexity and depth. It opens up a space of possibilities within what we consider as reality. More than that, it implies the fact that perhaps we need to think more carefully about the unrealistic or even the unattainable in order to preserve what is real.

“Poetry constitutes at the same time a question and a leap of faith to continuity. It maintains distrust against the “self-evident’, life as an act and not as mere survival, the thirst for meaning, the fight against the diffuse nihilism that surrounds us”. What role is poetry, and art in general, called to play in times of crisis?

Art works with its own laws. It constitutes a place of risk, imperilment, it is not easy to be inhabited, all the more when most people are not even given the chance, bombarded as they are with the propaganda of mass culture. The sociopolitical and economic crisis we are experiencing has brought forward the claim towards poetry to produce answers to urgent current matters of our society and in this way to become useful at last, to tell us something. Practically though this claim is asking to subordinate poetry (art) to the law of the market, turn it into a product. If I could think of a role, then I would think of it as a denial. A denial of defeat. Defeat presupposes that there could be a winning, a better whole which has been shattered, a paradise lost which is placed in the past or in the far future. And a denial of mourning, that is of the acceptance of a total dominion of the inescapable. We will never accept that they have won. That denial represents poetry for me, which insists to be saved within all that has already happened in the historical time, within disaster, the non-explicable past, within the transient and impermanent, within the secret, song, friendship and the erotic body.

Poetry is also the field where we can place, observe and experience the relationship of man with the non human elements, the animals, plants and inorganic world. In this realm, taking into account the falls, deaths, successive layers of interpretations and infliction, we continue in spite of it all, looking for companions against nothingness, against resignation from movement and possibility. Looking for a condition of togetherness. To look for a common language means I look for dialogue. The problem cannot be resolved, it does not “fit” in a specific place, but we insist to generate thought that is addressed to others, that creates narrative, therefore action, to memory as something active, we insist to desire the things that cannot be destroyed.

Photo Credits: Sofia Camplioni

Photo Credits: Sofia Camplioni

What makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

I am afraid the reasons that could make a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience, especially a poetry coming from a country of the periphery and a small language, lie outside poetry and have to do with circumstance. But circumstance can be an opportunity so that individual poets of a certain language can be heard. The poet is an observer whose testimony is both personal and cultural, but as an artist I try to move against the notion of a definitive tradition, or language or truth and towards a sense of homelessness, even exile. I think that most poets who write in Greek today are far from any notion of being representatives of a nation or tradition and this is one of the central characteristics of this phenomenon of new Greek poetry we are talking about. This stance however does not prevent many of them to deal with issues of national and historical identity.

The term national poetry though seems to look for a new circle of belonging, a new identity, terms of a specific community. Usually the ones who invoke a discourse of belonging are seeking for a discourse of sovereignty or they become its servants sooner or later. Greek and foreign do not exist as a duality anymore in contemporary art. Our influences are far more complex, shifting, diverse and constitute a place which is inhabited by a multitude of relatives, friends, brothers and sisters and companions, rather than parents (mainly fathers). We are exposed since our early youth in so much text, books in different languages, translated or read in the original. So many of the poets have studied abroad, they live and work abroad, the world we live in, digital or analog, is fluid, nomadic, porous in many ways (in other ways it is impenetrable but this is another discussion). And we are also in contact with the broader range of art in all its forms, which incorporates all genres. We have to find new ways to talk about influences, beyond national, linear or historical connections. The work of art is a kind of passage and because of it we are able to pass through borders, genres, constructions, deconstructions and transformations.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE