Novel Encounters, a festival celebrating Greek and Irish fiction, will take place from October 18 to 20. Organised by the Durrell Library of Corfu and the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting of the Ionian University, Novel Encounters aims to create a forum for Greek and Irish writers to discuss the issue of ‘Writing and Identity’. The festival will present four Irish novelists – Katy Hayes, Deirdre Madden, Mia Gallagher and Paraic O’ Donnell – and four Greek novelist, namely Christos Chrissopoulos, Panos Karnezis, Sophia Nikolaidiou and Ersi Sotiropoulos. The festival will also showcase translations relating to two Corfiot writers, Konstantinos Theotokis (1872-1923) and Theodore Stephanides (1896-1983) and translation will be discussed as a means of communication between cultures.

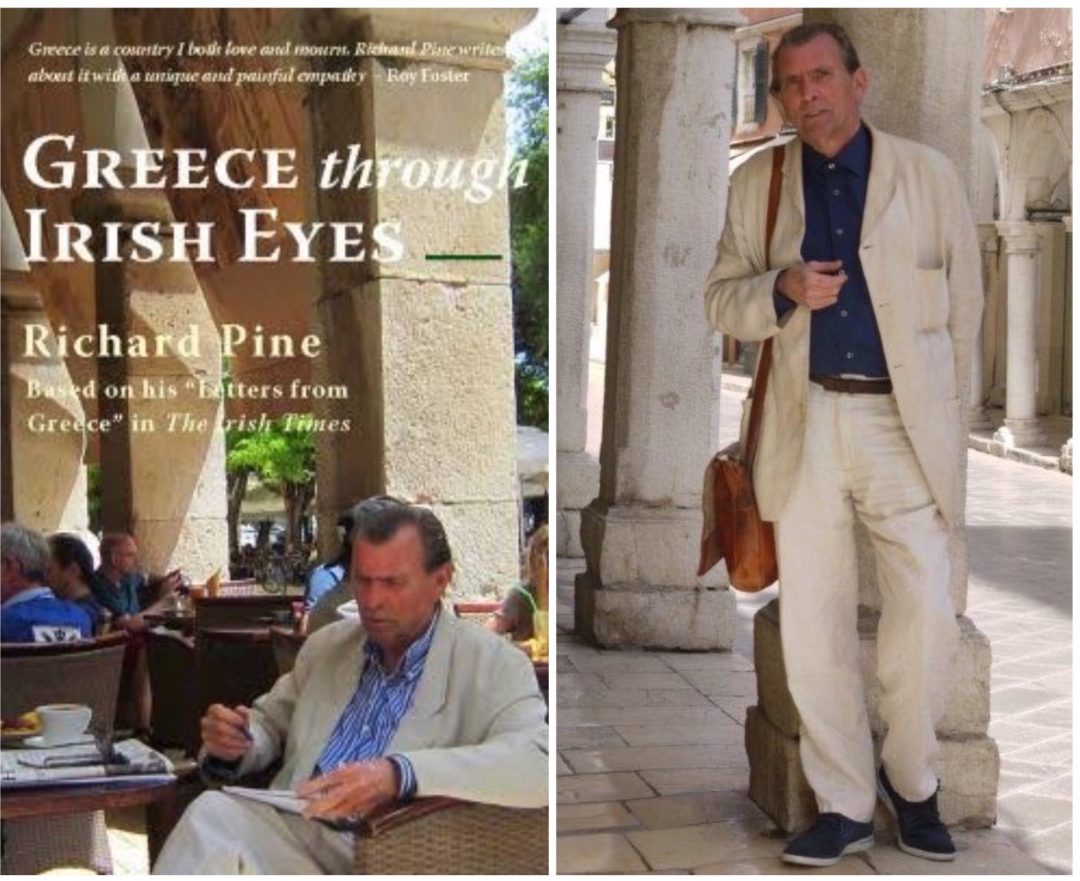

Reading Greece* spoke to Richard Pine, Director of the Durrell Library of Corfu (formerly the Durrell School), which he founded in 2002. Richard Pine was born in London, and educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Dublin. He worked as an administrator and editor in Radio Telefís Éireann (the Irish national broadcasting service) until his early retirement in 1999, in addition to pursuing his interests in music education, theatre history and media studies. He has presented and appeared in over 100 radio and television broadcasts for Radio Telefis Éireann and the BBC. He was for many years a trustee of the Royal Irish Academy of Music (of which he is an honorary Fellow), and deputy music critic for The Irish Times. He is also an obituarist for the Guardian newspaper.

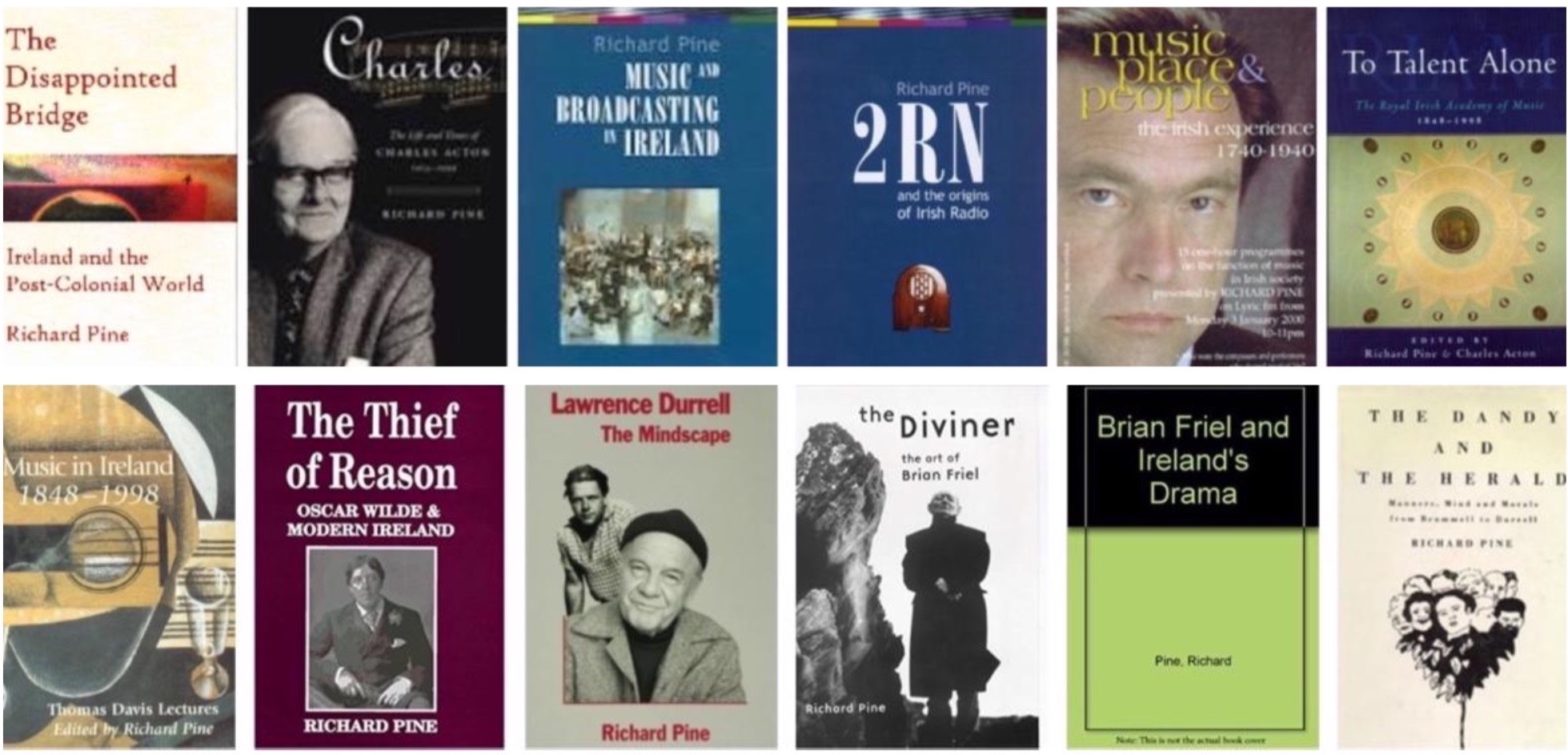

His twelve books include The Diviner: the art of Brian Friel (1990, 2nd edition 1999), The Thief of Reason: Oscar Wilde and Modern Ireland (1995), The Disappointed Bridge: Ireland and the Post-Colonial World (2014) and Greece Through Irish Eyes (2015). He lives in Corfu and writes a regular column on Greek affairs for The Irish Times; he was also a frequent contributor to the Anglo-Hellenic Review until it ceased publication in 2015.

Novel Encounters, a festival celebrating Greek and Irish writing, will focus on writing and identity. Tell us a few things about the scope of the festival.

The central theme is “encounter”: for the first time, four Irish novelists and four Greek novelists will meet and share their ideas about their writing and their place in their respective societies.

Each novelist will make a statement on the theme “Writing and Identity”. They will then read from some of their latest work. For the past few months, students at the Ionian University (Dept of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting) have been working on translating these pages and this is a central part of my philosophy – to involve Corfiot people in anything that we organise in the Durrell Library. Also, to reflect on Corfiot culture; in this festival, we have a special focus on translations of, and by, two Corfiot writers, Konstantinos Theotokis (1872-1923) and Theodore Stephanides (1896-1983).

The Irish participation is made possible by funds from the Irish Embassy but unfortunately no Greek funding body could give anything to pay for the Greek writers, so their expenses are paid by the Rothschild Foundation. It seems that at a time of austerity this kind of cultural funding is reduced or even disappears and this is entirely misguided: at a time of austerity, cultural funding should be increased, in order to make people more aware that there is a life beyond economics.

You have stated that Greece Through Irish Eyes was “the result of an urgent need to explain this country to Irish readers”. Greece and Ireland: Where do the two cultures converge and what are the main points of divergence? And, in turn, what are the main misconceptions about Greece in Ireland and in Anglo-Saxon countries in general? How has the narrative about Greece changed over the years?

I think from my long (50 years) experience of Ireland and my new (15 years) of experience of Greece, that the central issue in common for both countries is: where do we, and our distinctive cultures, belong? Joining the EEC (now the EU) was a major step for both cultures and their economies. When Karamanlis stated “Greece belongs to the West” he really started a great debate about the character and destiny of Greece. Is Greece really “western” in the implied sense of being “modern” – or is it irrevocably a Balkan country (arguably the focal point of the Balkans) with a very unWestern mindset that is not necessarily “eastern” either? Much “East-West” tension is misguided: east and west can live together and understand one another, but Greece is both east and west and should not be forced to choose between.

In the same way, Ireland is in many ways different from the mainland of Europe. It’s on the west, of course, but the “Celtic fringe” of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, even Brittany and the Basque country, has a celtic heritage that is quite different from the dominant culture of central Europe and the “great” powers that have dominated history and continue to dominate politics today. This distinctiveness should be maintained and celebrated.

Irish people probably thought very little about Greece except as a holiday destination until the economic crises made both countries very aware of each other. I don’t mean just the way Irish and Greek people experienced financial loss and insecurity. I mean something much deeper – the growing awareness that here are two peoples, on the peripheries of Europe and the EU, which they have never really been able to understand. They each have a huge mythology from prehistoric times, a strong relationship with the sea, a very significant diaspora, due largely to emigration during previous periods of crisis (such as famine), the experience of foreign domination and a war of independence, a civil war, and the transition from a rural way of life to urbanisation and a money economy. There is a very fertile imagination that makes their storytelling very vital, very persuasive, very resonant in the minds of all people who come from marginal cultures which are nevertheless deeply meaningful in terms of spirituality, chthonic presences and the relation of the individual to society.

The Irish poet Seamus Heaney became aware of the writings of George Seferis and understood this deeper level of appreciation of “topos” – of “where you are defines you”. And they both won the Nobel Prize to acknowledge this unique gift of conveying depth of meaning into the lives of ordinary people. I found the same characteristics in the writings of Alexandros Papadiamandis and Liam O’Flaherty (from the Aran Islands on the west of Ireland) – the same attention to small personal details, the same worship of the local, the same understanding of small things, so I drew them together in a chapter of my book The Disappointed Bridge: Ireland and the Post-Colonial World.

I continue to write a monthly column for The Irish Times on Greek affairs – and when he launched my book Greece Through Irish Eyes in Athens in 2015 the Irish Ambassador at the time, Noel Kilkenny, said that I was the main source of information about Greece for Irish readers. Some Irish readers criticise me because they think I am blind to Greek faults (which I am not!) and because they think Greeks have brought their troubles on their own heads and don’t require sympathy. But my answer is that I “love and mourn Greece” – that is, I celebrate what is great and beautiful about Greece and the Greeks, and I criticise where it is necessary, especially the burden of bureaucracy, the lack of planning in areas like tourism, and the failure to support cultural initiatives except with lip-service that doesn’t work.

In 2001 you founded the Durrell School of Corfu that, for thirteen years, hosted seminars on literature and the protection of the environment in the name of the brothers Gerald and Lawrence Durrell who had lived in Corfu in 1930s. How did you embark on such a venture? What about your experience after more than 15 years in Corfu?

I knew Lawrence Durrell quite well, and I wrote a book, which is the only comprehensive study of his work – including the unpublished work and his notebooks (Lawrence Durrell: the Mindscape, 1994, second edition 2005). I knew that I wanted to set up a “Durrell School” to explore the work of both brothers, Lawrence and Gerald, through the medium of international seminars and publications, and this succeeded for 13 years – about 25 seminars and seven books, including Theodore Stephanides’ Corfu Memoirs and a volume of essays on The Ionian Islands: their history and culture. These were important because I had the same philosophy right from the start: to involve Corfiots in our discussions and to reflect on the Corfiot heritage. This continues today in the “Gerald Durrell Week” in May each year, exploring the flora and fauna, which he celebrated in My Family and Other Animals. – this is supervised by Lee Durrell, Gerald’s widow, at the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust in Jersey.

I decided that Corfu was the most appropriate place because they had both lived here in the 1930s, each of them had, at that time, decided on the direction of their life’s work, which they owed to their experience in Corfu, and also because Corfu is such a cultural centre with such a fascinating history. I love this island and its people, and I’m going to die here and be buried here. I love the parts of the island interior that have not yet been spoiled by tourist development or the get-rich-quick boys showing off their new-found wealth, and especially I love Corfu city, a cosmopolitan centre of literature, music, painting, culpture for many centuries.

This festival is a new initiative of the Durrell Library, but I hope we will get the funding to follow it next year with a “Music Encounters” event bringing together Irish and Greek musicians and composers in association with the music department at the Ionian University – one of the best music departments in the whole of Greece. The new Irish Ambassador, Orla O’Hanrahan, has already identified cultural relations between Ireland and Greece as a key priority in her agenda, and we hope to work with her and her team in supporting this priority.

And then in 2019 I will be involved in a major new idea: creating a Chamber Orchestra of Irish and Greek music students. This is envisaged as a pilot project leading to the creation of an international training centre for the very specialised type of chamber orchestra playing, based in Corfu and run by the Royal Irish Academy of Music and the Ionian University, and involving students throughout Europe, but especially from Albania and southern Italy (with which Corfu has strong ties) as well as Ireland and Greece. But for this we have to find a major sponsor!

“Many of the problems that have arisen in the country’s dealings with its European partners over the last few years stem from the inability of non-Greeks to understand what Greekness is”. In your opinion, what are the constituent elements of Greekness?

In brief: first, the sense of a topos – of “being here”. Second, a commitment to family. Third, the deep sense of honour (filotimía) and dignity, and relationships outside the family, especially when they involve obligations such as debt – ipochréosi. Fourth, a sense of the past and a distrust in the future for themselves, but a sense of hope for their children.

I am an atheist, but, at the risk of sounding “old-fashioned”, these to me are “spiritual qualities” that are, as you say, “constituents” of Greekness, but let’s go further and say that they are the “heart” of Greekness. Even in today’s world of globalisation, multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism, it’s not shameful to acknowledge a sense of place, a set of cultural and ethical values and a way of living one’s life by those values. And I think Greeks demonstrate this more easily than most people.

“One of the items in my wish list is for more Greek writers to get translated into English”. Would you say that the Greek crisis has ignited the interest of foreign readers in Greek literature? And, in turn, does Greek literature have the potential to attract a foreign audience?

YES YES YES!!!! Not only do non-Greeks want to read the “great” or “classic” novels that they already know about (Kazantzakis, in particular) but they are now discovering what a huge wealth of literature exists. And if you look for example at the novels of Konstantinos Theotokis (recently translated by my friend Mark Davies, including Slaves in their Chains) or the stories of Alexandros Papadiamandis, you realise that although they were written a century ago they are still vibrant indicators of modern Greece and of all societies emerging from the mysteries of the past into the mysteries of tomorrow.

Because I can’t read Greek very well, I have to rely on translations. I once asked a friend why there are so many novels about war and misery – why not girls, and chocolate, and sunshine? His answer? There are of course these books in Greek but they don’t get translated because good news doesn’t travel so well as war and misery. And now? Due to austerity the funding for translation has disappeared! This is yet another example of the wrong-headed policy of retrenchment. There should be a multiple of the funding to create as much awareness as possible of the literary greatness of modern Greece among readers throughout Europe and the rest of the world.

And I don’t mean only “literary” work. I mean the thrillers by writers like Petros Markaris with Inspector Charitos, and someone I discovered the other day, Leo Kanaris’s Codename Xenophon – not only a good thriller but a sceptical view of the current crisis.

But in answering your question, let me say that, in bringing together the Irish novelists and the Greek novelists, there could be almost no end to the Greeks we could have invited: I personally am fascinated by works like Fotini Tsalikoglou‘s The Secret Sister and the novels of Ioanna Karystianni and Yiorgi Yatromanolakis, and luckily these are available in translation. But there are so many more and the Greek authorities are not doing enough to make us aware of them!

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read more: Reading Greece: Ersi Sotiropoulos on the Correlation between Art and Life and Literature as a Way to the Non-Existent and the Inevitably Potential; Reading Greece: Sophia Nikolaidou on the Representation of Greece’s Political Past in Contemporary Literature, the Prospects of the Greek Educational System and Literature as a Human Learning Experience; Reading Greece: Christos Chryssopoulos, Writer at Home, Photographer at Large

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE