Photo by Panagiotis Gavriiloglou

Playwright, novelist, scriptwriter and now librettist: Vangelis Hatziyannidis is a man of many talents, who does not stay in his comfort zone but takes on new challenges, whether this means different genres or unfamiliar themes. He’s not, however, a chameleon, but a creator with a distinct personal style and artistic identity.

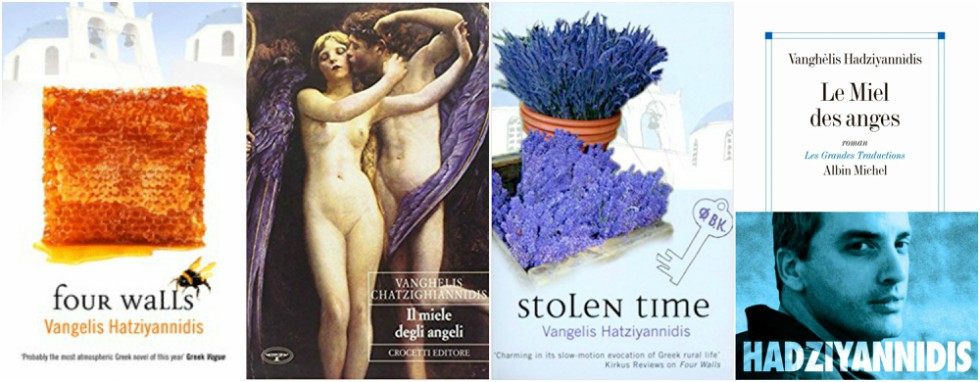

His first novel, Four Walls, was awarded Diavazo literary magazine’s “Prize for a First-Time Author”, in 2001. It has been translated into English, Spanish, French, Italian and Portuguese. In France the book won the Laure Bataillon Prize for the best translated novel of the year. In its English translation, it was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. His second novel, Stolen Time, has also been translated into English, Spanish and Italian.

He has also written the plays Disguise, Mud, La Poupée, Screen Light, Cake and others, all published and staged in Greece. La Poupee has met with great success and stellar reviews, while Screen Light won the Public Prize at Heidelberg theatre festival 2013. He also co-authored the screenplay for Marsa Makris’ film Sacrilege (2017). His most recent venture is the Greek speaking opera Z, based on the eponymous book by Vassilis Vassilikos, for which he collaborated with internationally acclaimed composer Minas Borboudakis and noted stage director Katerina Evangelatos.

Z (1966) is a political novel based on true events taking place during the tumultuous for Greece 60’s, which culminated in the military coup of 1967. It recounts the assassination in 1963 of MP, physician and athlete Grigoris Lambrakis (presented as “Z” in the novel) by far-right extremists, orchestrated by members of the police forces, and the determined efforts of an unrelenting prosecutor to find the culpable and unmask the conspiracy. It was adapted into an acclaimed film (1969) by renowned director Costa-Gavras, starring Yves Montand and Jean-Louis Trintignant. An opera adaptation of this work, especially in Greek, was an ambitious and daring project, and the result does not let down. We spoke* with Hatziyannidis about his latest ventures and future plans.

Z, the opera – Photo by Gerasimos Domenikos

Z, the opera – Photo by Gerasimos Domenikos

When adapting the novel Z into a libretto, how faithful did you remain to the original? Were you influenced by the film version by Costa Gavras?

Well, I started by going through all the material, very thoroughly. I read the book repeatedly, and watched the movie a couple of times; I also studied the era, the political and social situation in Greece at the time, the circumstances surrounding the event and, in the end, drawing from all this material, I made my own composition. Moreover, through conversations with the music composer, Minas Borboudakis, we reached a conclusion concerning the elements we wanted our opera to contain. Our main influence was, of course, the novel, while we used almost nothing from the film. The director, Katerina Evangelatos, didn’t base her work on the film either, from a visual point of view, since that was a work from another time and a different genre.

As a result, we identified the elements that interested us in the novel, but distanced ourselves considerably from the actual text. We located specific parts where the narrative was more poetic, and we brought them out in a different way, using different wording, a different type of discourse. We also focused on points of the novel that don’t seem pivotal within it, such as those where characters are studied in depth. Character study and lyricism are the two elements that are central in our opera, unlike their lesser importance in the book.

In the programme, you state that the greatest challenge for you was not posed by the opera as a form, but by the subject: you had never before engaged in the genre of political thriller.

That is true. But I was fortunate to share the same views as Minas (Borboudakis) concerning the way we wanted to treat the story. That was one of the reasons we could work together perfectly; our visions and our aesthetic preferences coincided. The political novel, and generally the issue of politics in art, has been a widespread tendency in Greece and the rest of Europe for decades now; this is ever more prominent in theatre – take, for example the German scene, which is considered the steam engine of European theatre. And yet I was personally never attracted to this type of writing. But this didn’t pose an obstacle for me. On the contrary, I could delve into this material with new eyes, the eyes of a person who avoids the use of politics in art, something I think proved beneficiary to the work.

Tell us, what is the process of authoring a libretto? How is it related to the musical composition?

Well, for a period of about three months we skyped a lot with Minas, who lives in Munich, holding long conversations concerning the opera’s structure. As I said, our views coincided to a great extent, even our initial thoughts before meeting with each other, so there was a lot of common ground to begin with. We talked about the structure, the way the inner voices of the characters would be manifested in parallel with the unraveling of the actual events, about which characters would be at the centre of the narrative, and, after agreeing on the broad outlines, I took this material and wrote an entire libretto which took about two months.

Minas then took this first version and began composing the music. As he proceeded from one scene to the next, he shared with me various thoughts that came up, some issues concerning the pairing of the text with the music. For example, he would ask for a few more lines to be added to a monologue, or he would need a phrase with a particular metric pattern. That was a very entertaining part of the process, these small modifications; some were quite difficult to achieve, but they were like riddle for me to solve: I had to convey a certain meaning in a phrase with a standard set of words and syllables, and a particular intonation. All this seemed like a puzzle that I really enjoyed and which gave me the opportunity to further explore language as a tool.

Z, the opera – Photo by Gerasimos Domenikos

Z, the opera – Photo by Gerasimos Domenikos

Your great success, La Poupée, was a musical. Did that experience help you with Z?

No, there is no comparison. For La Poupée I wrote the lyrics for a number of songs, but this is totally different. The libretto didn’t rhyme; it only has a particular rhythm in certain parts. In opera, the entirety of the text is sung out or, even when it is uttered as prose, it is metred and words have to be spoken in a specific way. The actor portraying “Z” doesn’t sing at all throughout the play, but he has to talk in a specific manner, within a very specific time, because it is still perfectly synchronised with the music. In La Poupée, there were five songs during the performance, but that didn’t affect the rest of the play.

How did you decide to make “Z” a non-singing character?

That was a deliberate decision by Minas Borboudakis. “Z” has many lines where he delivers a political address, which would sound awkward in song, so he opted for prose whenever “Z” speaks.

What are the main differences between writing a play and a libretto?

Let me start with the similarities. In both cases, one must create a dramatic work: introduce the characters and give the audience some information about them; each character must have a purpose, a clear goal to pursue and follow a certain course from the beginning to the end of the play. Moreover, the play must have a climax, creating suspense for the way it’s going to end. Opera and theatre have all these in common; the difference lies in the need for a particular metre in opera and also in the fact that the lines are sung, tripling the time it takes them to be uttered. Consequently, a libretto must be about one third the size of a play of the same length. Thus the dialogue must a concise as possible, using only those words that are absolutely necessary.

Do you think that this was a one-off venture, or an endeavour that may interest you again in the future?

When I received the proposal from the Greek National Opera’s Artistic Director, Giorgos Koumendakis, and Alexandros Efklidis, Artistic Director of the Alternative Stage of the Greek National Opera, it had never crossed my mind that I could be involved in writing a libretto. In spite of the difficulties faced, lacking relevant experience, the whole process ultimately proved very entertaining -I use this expression again- and I really enjoyed it, plus I learned a lot. And, although there is not a great demand for operas, especially compared to the demand for theatre plays in Greece, it would be a pleasure to do it again, given the opportunity.

Photo by Dora Tsouri

Photo by Dora Tsouri

There is no Greek opera tradition. Do you think that this could change?

It’s one of the central missions of the Greek National Opera, under the direction of Giorgos Koumendakis and Alexandros Efklidis, to commission operas from Greek composers / librettists. I hope the effort bears fruit, producing works of quality that may succeed beyond our borders.

You have also delved into another genre, writing the script for Marsa Makris’ film Sacrilege. How was that experience, compared with the other two?

Naturally, writing a screenplay is a different experience altogether. I co-authored it together with the director, we collaborated closely and, as Marsa knows the language of cinema very well, it was easier for me not to carry the responsibility on my shoulders alone. I also enjoyed this venture very much, and I am currently in the process of writing a new screenplay, in collaboration with another film director. By way of my experience in these different genres, I end up discovering more similarities than differences, and I can examine the process of writing more thoroughly through these diverse approaches.

There is a recurring theme in some of your novels (i.e. Four Walls) and plays (Butterfly in Well), as well as in the film Sacrilege: that of a people restricted in a confined space.

Yes, I feel that this confinement – which can be in a room or in a building, or as in the case of Four Walls the added isolation of living on a small island – helps me focus more on the characters, it’s like cornering them with a magnifying glass so that you are able to study them in depth and detail. It is the equivalent of a close-up shot in cinema, revealing the subtlest expressions. I felt that I could put my heroes under a microscope this way.

You have tried out several different genres. Is one of those closer to your heart? Would you for example identify more as a playwright or a novelist?

Every time I work within a certain genre, I feel more at home there. And I know that it’s an illusion, and that when I start working another genre I’m going to feel the same thing. I feel equally in place with both prose and theatre. I enjoy this variety, like having two different houses, one in the city and one in the country. I feel that literature is my base, since I have engaged myself in it much longer and but, on the other hand, I feel a greater intimacy in theatre, because I know it from the inside on account of my early studies and work as an actor. Both are very important to me. Thankfully, I don’t actually have to choose!

Works by you have been translated you have been translated into 5 different languages.

Works by you have been translated you have been translated into 5 different languages.

And my first two novels are about to be published in Turkish too.

It is not always easy for a Greek writer to attract the interest of foreign publishers.

Like all good things in life, this thing just came about in a rather happenstance way; when my first novel came out, Michel Volkovitch (well known for his translations of Greek works into French) read it and called me to say that he was interested, then the same thing happened with Italian translator Maurizio de Rosa (also prominent in his field), and these two cases kind of set things in motion, I guess. Volkovitch’s translation won the Laure Bataillon Prize, an award jointly granted to both author and translator, while Anne-Marie Stanton-Ife‘s translation into English was shortlisted for the “Independent Foreign Fiction Prize”.

This of course was very gratifying for all – me, translators and publishers. Through translation you feel you can reach out to foreign readers, not so much in the sense of just expanding your readership, but more in the sense of appealing to different people of different nationalities, mentality and aesthetic views.

Do you think that the universality of your characters -as opposed to the evident “Greekness” often found in other works- appeals to foreign publishers?

It could but, on the other hand, the quest for a politicised art, which I referred to earlier, can make others more prone to publish works that are more local in character, with many references to current sociopolitical issues. But, whatever the focus of a book is -politics, social issues, romance, metaphysics etc- it all comes down to one thing: you have a bad novel or a good novel; an author who triggers your interest or not.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Read more on Lambrakis and the post-Civil War period in Greece: Rethinking Greece: Evi Gkotzaridis on the ‘long’ Greek Civil War, the ‘deep state’ and historical Revisionism

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Composer Minas Borboudakis on his work in 21st-century classical music; Film Director Marsa Makris: “In the end, it is the enigma that feeds the imagination”; Kostas Georgousopoulos on contemporary Greek Theatre; The Greek Play Project: Mapping contemporary Greek theatre; Contemporary Greek theatre in the spotlight