Denise Harvey is a small independent publisher, working from Evia (or Euboea), a large island not very far from the Attica region. Born in the UK, she moved to Greece more than fifty years ago, enchanted by its history and natural beauty. As she says in her site, living there made her realise that “there was a Greece to pursue beyond the demarcations of history and dates and its physical beauty […] something beyond that which immediately gives [people] delight and pleasure in the Greece they encounter today”.

Denise Harvey’s publications feature books that are primarily, but not exclusively, concerned with various manifestations of the culture of modern Greece: its literature, history and music, “its natural beauty and forms of life in both city and country, how Greek people see themselves and others, and how others see them, and the Orthodox Church that is the matrix within which much of what can be defined as modern Greek culture has been formed”. We interviewed* Harvey on her experience of living in Greece, her perception of contemporary Greek culture and the struggles of maintaining a small book publishing company today.

What is it that attracted you to Greece in the first place?

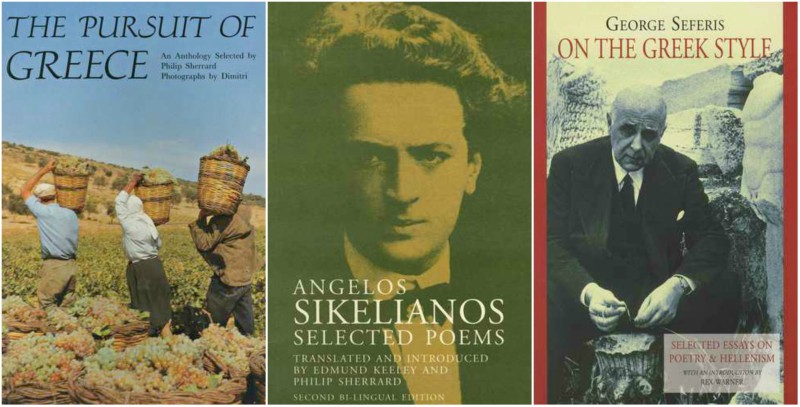

I seem to remember that the seed was sown by a travel article in an English Sunday newspaper about Monemvasia which had been sent to me by a friend: it described wonderful stone houses, narrow streets, no electricity, a handful of people still clinging to their traditional way of life. I was at the time living and working in Germany for USAFE (United States Air Forces in Europe) at Weisbaden. The base had a magnificent library facility for its personnel, with a most sympathetic librarian in charge of it, so I went there to find some books about Greece, present-day as opposed to ancient Greece, and came home initially with a book entitled The Pursuit of Greece, an anthology of writings selected by Philip Sherrard, with many evocative full page black and white photographs by Dimitri Papadimos.

That book made an enormous impression on me. Its Introduction explores the spell that Greece has cast over so many people and how its modern post-Byzantine image assumed new dimensions, a new complexity. In it I read my first translations of Greek poetry — Sikelianos, Elytis, Seferis, Karouzos — and texts by such people as Patrick Leigh Fermor, Alexandros Papadiamandis, Robert (not Lord) Byron, Fotis Kondoglou, Kevin Andrews, and Silouan of the Holy Mountain. It was as if I had come under the spell without even having set foot there. Not many more months passed before I did.

In your site you quote Philip Sherrard (many works by whom have been published by you): “Greece is not and never has been a lost paradise or a haven for tourists or an object of study, and those who approach her as if she were any of these will always fail to make any real contact with her”. Does this phrase express your own thoughts? How do you think Greece can be really understood?

This quotation comes from the end of the Introduction that I refer to above and I do agree with it, although of course for many it has been a lost paradise, tourist haven and an object of study. The first important influence on Philip was George Seferis whose poetry he began to translate into English shortly after his first visit to Greece in 1946. Lines from a letter that Seferis sent him particularly impressed him:

‘There is a process of humanisation in the Greek light . . . Just think of those cords that bind man and the elements of nature together, this tragedy which is at once natural and human, this intimacy. Just think how the light of day and man’s blood are one and the same thing.’

Of Seferis, Philip later wrote:

‘It is as if Seferis thought, not by discursive reasoning but intuitively, in terms of natural objects, in terms of sensual images. It is as if the subject of his thought revealed itself to him not as an abstraction divorced from the rest of life, but in all its relationships not only to other ideas but to nature as well.’ I think these two quotations help to explain the ‘real contact’ Philip writes of in his Introduction, which, to quote him again, he saw as a search for ‘the living fate of Greece, which is not a doom but a destiny, a process rather in which past and present blend and fuse, in which nature and man and something more than man participate.’

I think these two quotations help to explain the ‘real contact’ Philip writes of in his Introduction, which, to quote him again, he saw as a search for ‘the living fate of Greece, which is not a doom but a destiny, a process rather in which past and present blend and fuse, in which nature and man and something more than man participate.’

As to the reason why I have published many works by Philip Sherrard, it is simply, but not only, that some ten years after I borrowed that book from the library in Germany I actually met him in Athens, and went on to marry him, and have since reprinted a number of his writings when the original editions went out of print, including — how could I not! — The Pursuit of Greece.

How did your interest in Modern Greek literature develop?

My first two years in Greece I spent in Mani, then moved to Athens in 1969. The dictatorship notwithstanding, and in some ways because of it, it was a very exciting place to be. The cost of living was minimal and rents were cheap and enabled a bohemian way of life that was very attractive to aspiring poets, writers and young scholars, mainly non-Greek, most of whom, like me, had come to Greece before April 1967 when the colonels staged their coup. The Greek element of serious committed literary people was always present at our gatherings; many were the evenings when the tavern owner closed his shop down and left us at his tables with a good supply of wine and we talked through the night. Not a small number of our company were active in the resistance to the dictatorship, and not silent about it either. During those years, in addition to other jobs I worked as a ‘stringer’ and journalist -I remember one of the pieces I wrote was on Greece being a nation of poets with statistics on how many volumes of poetry were published each year, an unbelievable number- and I also produced books for the academic publisher Adolf Hakkert and an occasional volume for Oxford University Press. Those activities brought me in touch with a lot of people in the literary world in Greece.

Do other foreign nationals share that interest? Have your publications managed to attract a viable readership?

I hope they do but fear that now a great many of them probably do not. Greece is no longer a haven for penniless foreign writers who are the most faithful supporters of small publishers like myself when it comes to buying books about the literature and culture of the country they are presently living in. One can no longer live in Greece on a shoestring. It would seem to me that foreign nationals with sufficient money to buy books are for the most part in the business world and on the whole they simply do not have the time to search out and read such books. Another factor is that, because of the economic crisis, the majority of bookshops still surviving in Greece are unable to stock books on their shelves as they used to in the past, and so they mostly upload titles with limited popularity on to their websites and only order them if they get an actual firm order for a particular title. That’s a very different way of finding a book which one maybe is attracted to read. Lost is the delight of discovering something which really interests one among a host of others on a shelf in a bookshop, and then flicking through it to get a taste of it; and not only that but having the opportunity to appreciate the quality (or not) of the publication, its design and general feeling. A book is a material thing and its content should participate in and contribute to its physical presentation, but that seems to happen less and less nowadays.

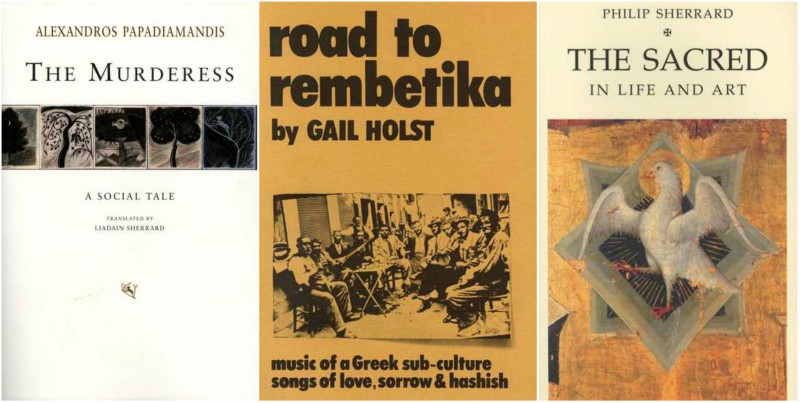

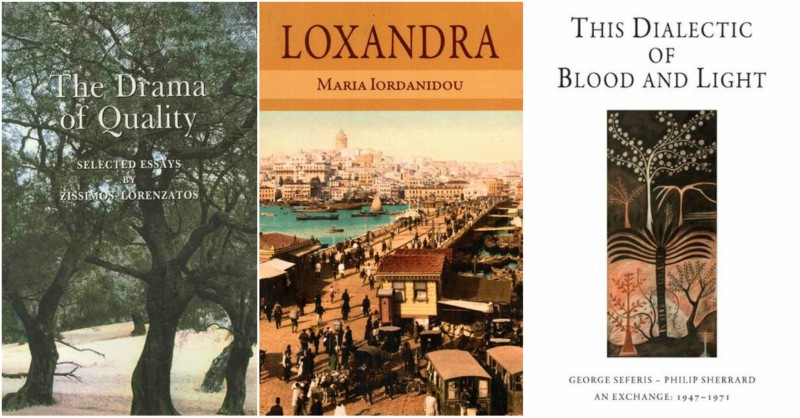

So, along general lines, I have to say that my readership is really very much on the edge of being ‘viable’. My two publications on rebetika music (one in English, the other in Greek) still sell steadily albeit slowly after many years, for which I am grateful, and somewhat surprisingly the translations of Papadiamandis haven’t done so badly, and neither have the poetry translations, but, for instance, the selected essays of Zissimos Lorenzatos (The Drama of Quality), who was one of modern Greece’s most significant men of letters, hardly sells at all. Also, my most recent publication, Loxandra by Maria Iordanidou, which is about a Greek family living in Constantinople before the first World War and which has been and still is one of the best selling titles of all time in Greece that one might describe as an iconic book for Greeks, has been almost totally ignored by the English book buying public in Greece and Greek booksellers generally. The biggest surprise is the book I first published in 2005: Wounded by Love, The Life and Wisdom of Elder (now Saint) Porphyrios, which was translated from the Greek original published by the Holy Convent of Chrysopigi in Crete. It is a very unusual book, and written in a way totally different from most hagiographic books published in Greece, and is constantly in demand, a revealing indicator of spiritual hunger — ‘man is . . . thirsty like the grass’ as Seferis puts it his long poem ‘Last Stop’.

Since the outbreak of the crisis, has foreign interest in Greek literary production been affected negatively or positively?

I’m afraid that I can’t answer that. Working from my home on a Greek island, Evia, albeit an island that is accessible to the mainland by road, and no longer being in Athens, or in London, or some capital city somewhere, I am very much on the fringe of things, and although I keep in touch with what is being published in English translation from the Greek I don’t know how successful those publications actually are. To move permanently from Athens to Evia was my choice of course, and I don’t regret it. Decentralisation was for me an important thing even before the ‘crisis’ hit. I think it is an important concept for Greece generally, for all those who can manage it, and especially now with the present economic situation. Among your publications of works of fiction or poetry we find almost exclusively titles from modern classics. Is it because you find no particular interest in recent contemporary Greek writers or does it have to do with a specialisation, a specific profile you want to maintain for your editions?

Among your publications of works of fiction or poetry we find almost exclusively titles from modern classics. Is it because you find no particular interest in recent contemporary Greek writers or does it have to do with a specialisation, a specific profile you want to maintain for your editions?

Alas, the lack of contemporary Greek writers in the books I publish is mostly due to economic reasons. In the ‘old days’, let’s say from the First World War onwards, people interested in literary treasures from another culture, if they had the capacity to do so, translated those texts into their mother language out of love and admiration for the original texts. They were not commissioned to do so, and I think they were very rarely paid for it except perhaps after publication, if in fact the work was subsequently published; their satisfaction came from the delight of sharing it with others, and it was also a way of establishing their credentials as a literary person, especially through the medium of literary journals where such translations were mostly first published. Then, in Greece anyway, and I am sure elsewhere, there were also some writers who had the economic facility to pay a translator to translate their work or works in the hope they would subsequently interest a publishing house outside Greece. This rarely happens anymore.

If somebody would come to me with a fine English translation of the work of a contemporary Greek writer, of course I would consider it for publication and I would especially welcome that. But with regard to your question of ‘viability’ above, the chances of it selling in sufficient numbers to cover even its production costs is for me something of a gamble, which concomitantly means that usually I am not in a position economically to pay for its translation as well. I don’t have the promotional machine that is needed nowadays to launch and sell a book as they are presently marketed by major publishing companies; selling books has become, like so much else, something of a cut-throat business and I have to rely on the work’s intrinsic quality for it to sell — which I do, and which, with considerable patience, pays out in the end. That is not to say that if I suddenly found myself with a best seller on my hands then of course there would be provision for its translator to benefit as well.

Does Greece lack a comprehensive state policy related to the support of publishers and the promotion of Greek book production?

At present I would say it does, not in principle but in kind: but how could it be otherwise these days given the country’s ‘hard times’? Fortunately there are a number of Greek philanthropic organisations that try to fill that gap, and all must be grateful to them, as one must also be to a surprising number of people who do not necessarily have an obvious connection with Greece but who support cultural endeavours within it in many and often unsung ways.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

*INTRO IMAGE: Denise Harvey with Philip Sherrard

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Athens – World Book Capital City of 2018; Dimitris Sotakis on the Potential of Greek Writers and the Appeal of Greek Literature Abroad; Popi Gana on the Current Challenges and Future Prospects of the Greek Book Market; Evangelia Avloniti and Katerina Fragou on Greek Literature Abroad & the Greek Book Market; Richard Pine on Greek-Irish Encounters; “Teriade”: an Art enthusiast seen by Simos Korexenidis; Rebetiko music: From the margins to the mainstream