Zdravka Mihaylova is an accomplished and prolific translator of Greek literature into Bulgarian. She was born in Sofia and is a graduate of the Sofia University School of Journalism and Mass Media. She has worked as a journalist for the Bulgarian State Radio and the Bulgarian News Agency (BTA). Since 1994 she has been working at the Greece & Cyprus desk of the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while continuing to write articles on Greek literature and cultural heritage. She has, to date, had three postings at the Embassy of Bulgaria in Athens (1995–1998, 2002–2005, 2009–2013).

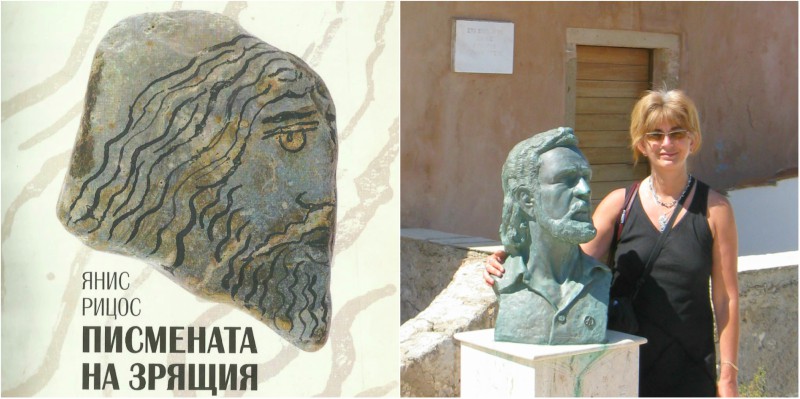

As is a literary translator from Greek and Bulgarian, she has translated 45 books of contemporary Greek writers as well as some books from Bulgarian. In 2010, she received Greece’s State Translation Award for the translation of a work of modern Greek literature into a foreign language, for her anthology of poems by Yannis Ritsos «Η Γραφή του Παντόπτη» (Stigmati Publishers, Sofia: 2009). Zdravka Mihaylova spoke* to Greek News Agenda on literary translation as a platform of communication between cultures and peoples.

How known is Greek literature in Bulgaria?

Looking back at the reception of Greek literature in Bulgaria, one could say that in the 18th and 19th centuries highly educated Bulgarians used the Greek language as a conduit for communicating with European culture. This is the reason that not only ancient Greek classical writers and philosophers have been published in Bulgarian in repeated editions, but there is a significant and sustained tradition of translating modern Greek literature.

Works of Greek prose were translated abundantly, particularly in the period 1960–1990, but also in the new market conditions after 1989. Along with the quartet of Greek poets known by every well-educated Bulgarian reader – Cavafy, Seferis, Ritsos and Elytis – Nikos Kazantzakis is the most well-known, translated, widely read and best-selling Greek author, with more than a million copies printed.

Kazantzakis’ oeuvre in Bulgarian language is inextricably linked with Georgi Koufov (1923–2003), a devoted translator and a connoisseur of the author’s work. Koufov’s output includes also translations of works by Kostas Varnalis, Emmanouil Roïdis, Dido Sotiriou, Dimitris Hatzis, Stratis Doukas, Maria Iordanidou, Menelaos Loudemis, and many others.

Bulgarian readers are also familiar with classical works of Greek literature, such as Stratis Myrivilis’ Life in the Tomb, Grigorios Xenopoulos’ Rich and Poor, Ioannis Kondylakis’ Patouchas, Andreas Karkavitsas’ Words from the Prow, in several translations. In 1963, on the hundredth anniversary of Cavafy’s birth, a collection of translated poems by the great poet was published in Bulgarian by the largest – at the time – national publishing house Narodna Kultura, which had a great impact on the Bulgarian public.

Bulgarian readers are also familiar with classical works of Greek literature, such as Stratis Myrivilis’ Life in the Tomb, Grigorios Xenopoulos’ Rich and Poor, Ioannis Kondylakis’ Patouchas, Andreas Karkavitsas’ Words from the Prow, in several translations. In 1963, on the hundredth anniversary of Cavafy’s birth, a collection of translated poems by the great poet was published in Bulgarian by the largest – at the time – national publishing house Narodna Kultura, which had a great impact on the Bulgarian public.

How would you assess the interest for translations of modern Greek literature today?

During the last years there has been a steady interest in all Balkan literature, including Greek. After 1989, and following a brief switch of readers’ attention to banned-until-then works by Western writers, interest in modern Greek literature has been reinvigorated. Since 2000, many Greek writers and poets have appeared in Bulgarian translations: Ioanna Karystiani, Dimitris Kalokyris, Margarita Karapanou, Rea Galanaki, Thanassis Valtinos, Takis Theodoropoulos, Zyranna Zateli, Ismini Kapandai, Elena Houzouri, Dimosthenis Kourtovik, Kostas Kalfopoulos, Thomas Skassis, Yannis Varveris, Michalis Ganas, Takis Sinopoulos, Nikos Karouzos, Haris Vlavianos. There also playwrights, whose work has been translated and featured either as separate publications, or in literary journals or who have appeared as guest lecturers in Modern Greek Studies departments. These include Pavlos Matesis, Dimitris Kechaidis, Vassilis Ziogas, Marios Pontikas, Loula Anagnostaki.

How do you think literary translations affect communication between peoples?

We must acknowledge the great value of literary translation in facilitating acquaintance and communication between different cultures and peoples, especially in the Balkans. Communication between the Balkan peoples is still difficult, mainly because of the language barrier, which prevents us from realizing the existence of a common, fundamental Balkan civilization among all the peoples of the peninsula. Indeed, the peoples of the region have little knowledge of the peculiarities of their neighbors or their literary landscape. The channels of cultural communication between them had, until fairly recently, usually passed through the major European centers of art and creativity, such as Paris, London, Moscow or Berlin. For a work to be translated into one of the Balkan languages, it had to have already received the imprimatur of critics or to have attracted the public’s interest in one of the major European languages. Direct translation from Greek to Bulgarian, and vice versa, has sought to symbolically remove this communication barrier and constitutes a first-rank cultural event. In view of the prevailing domination of the major languages, literary communication between the so-called “weak languages of limited dissemination” is a palpable manifestation of the significance, autonomy and cultural specificity of the “small” or less spoken languages of Europe that deserve to be supported.

Finally, since we are talking about the importance of literature and literary translation in fostering communication and acquaintance between different cultures and peoples, how well-known, or maybe not, is Bulgarian literature in Greece?

The relation between Bulgarian titles translated into Greek and Greek literature, whether ancient or modern, available in Bulgarian, is somewhat unbalanced. Many more Greek authors have been translated into Bulgarian than the other way around. Classic Bulgarian novels like The Peach Thief, Anti-Christ, The Legend of Prince by the renowned-abroad writer Emiliyan Stanev have not been available in Greek since the 1980s. One of the iconic works of Bulgarian literature, written by its patriarch Ivan Vazov – Under the Yoke – would grab the interest of anyone interested in historical novels, with its exceptional writing and suspenseful plot. It is out of print too, as is the novel Tobacco by Dimitar Dimov, which refers to a complicated period in the history of Bulgarian-Greek relations: the Bulgarian occupation of Eastern Macedonia and the Greek part of Thrace (1941–1944).

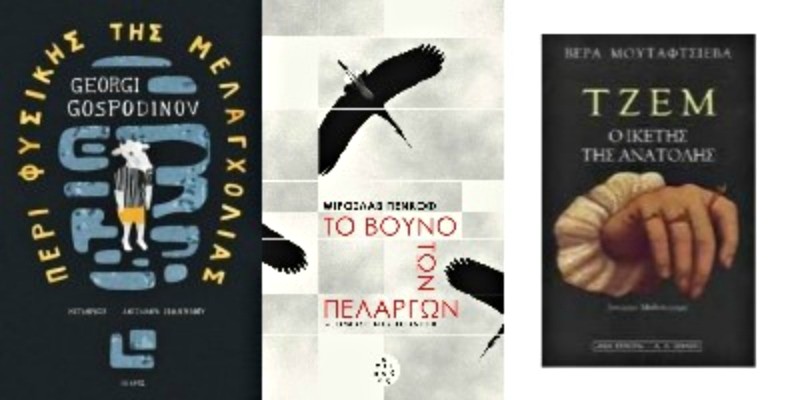

More recently, I recommend a more contemporary Bulgarian author – Vera Mutafchieva – more readily available in Greek editions. Her books directly relate to Greece and its history: to ancient Greece, to the glory of Byzantium and to Ottoman intrigues. Bay Ganio, a venerable text satirizing an uncouth, nouveau-riche Bulgarian character during the era shortly after the Bulgarian liberation from Ottoman rule, who tours Europe trying to sell his rose oil, or embarks on political intrigues while in Bulgaria, will soon be translated by Vaïtsa Hani-Moÿsidou.

Poems by the Bulgarian poet Kiril Kadiiski are available in a discrete edition. I have presented many others, both poets and prose writers, at literary festivals – for example, Todor Todorov, a short story writer, and poet Nadezhda Radulova at the ‘Logotehniki Skini’ Festival in Kalamaria (2013); the poets Sylvia Choleva, Patricia Nikolova, and Yordan Eftimov at the Transbalkan Poetry Festival under the aegis of the Thessaloniki International Book Fair; Ivan Theofilov, Sylvia Choleva, and Palmi Ranchev at the Rhodes International Writers’ and Translators’ Center; and five Bulgarian poets at the Prespeia Festival (2000). Very recently, Georgi Gospodinov (born 1968), one of the most talented and translated modern Bulgarian writers, was introduced to the Greek readership with his last novel, which had already appeared in English as The Physics of Sorrow (2015).

Poems by the Bulgarian poet Kiril Kadiiski are available in a discrete edition. I have presented many others, both poets and prose writers, at literary festivals – for example, Todor Todorov, a short story writer, and poet Nadezhda Radulova at the ‘Logotehniki Skini’ Festival in Kalamaria (2013); the poets Sylvia Choleva, Patricia Nikolova, and Yordan Eftimov at the Transbalkan Poetry Festival under the aegis of the Thessaloniki International Book Fair; Ivan Theofilov, Sylvia Choleva, and Palmi Ranchev at the Rhodes International Writers’ and Translators’ Center; and five Bulgarian poets at the Prespeia Festival (2000). Very recently, Georgi Gospodinov (born 1968), one of the most talented and translated modern Bulgarian writers, was introduced to the Greek readership with his last novel, which had already appeared in English as The Physics of Sorrow (2015).

Well aware of the importance of organizing events that bridge our two cultures, the Museum of Byzantine Culture and the General Consulate of Bulgaria in Thessaloniki co-hosted, in December 2017, a double book presentation of a Greek and a Bulgarian title respectively: the classic collection Balkan Legends and Myths by Yordan Yovkov (2016) and The Death of the Knight Celano and other stories by Thessaloniki-born Theofano Kaloyanni, published in Bulgarian in 2013. The two books, though very different, have Balkan myths and legends as a “common denominator”.

Finally, it would be an omission not to mention, with well-earned respect, the contribution of such profoundly knowledgeable translators of modern Bulgarian literature into Greek as Panos Stathoyannis, Dimitris Allos, Hristos Hartomatsidis, Vaïtsa Hani-Moÿsidou and others.

* Interview by Evgenia Kampaki, Press Officer at the Embassy of Greece in Bulgaria, on behalf of Greek News Agenda

N.M.