Gerassimos Moschonas, PhD (Doctorat d’Etat), University of Paris-II, is currently an associate professor in comparative politics in the Department of Political Science and History, Panteion University of Political and Social Sciences, Athens, Greece. He was a visiting scholar at the Universities of Princeton, Yale, and Paris-II and has extensively taught as a visiting professor at foreign universities, notably the Free University of Brussels, Montpellier 1, and Paris 8.

Professor Moschonas is the author of In the Name of Social Democracy, The Great Transformation: 1945 to the present (Verso: London, New York, 2002) and La social-démocratie de 1945 à nos jours (Montchrestien: Paris, 1994). He has written extensively about European integration, Social Democracy, the Radical Left and the Greek Crisis in international newspapers and magazines. His current research is focused on the history of the European Left, the European Union and political parties, with particular emphasis on the parties of social democracy and the radical left, the Europarties and the Greek debt crisis.

Gerassimos Moschonas spoke to Rethinking Greece* about Εuropean Democracy, the Left’s prospects in Europe, Greek state building and political modernity as well as Syriza’s capacity to promote progressive reforms in Greece

download the interview in pdf format

One of the central findings of a nation-wide survey, recently conducted by diaNEOsis foundation under your supervision, is the consolidation of a new kind of Euroscepticism in Greece. How does this trend relate to similar trends in the rest of Europe?

Up until the crisis of 2009, Greece was a markedly pro-EU country. Since the onset of the 2009 crisis, however, a significant shift has been documented in the findings of the Eurobarometer and explored in greater depth in the Dianeosis survey and Dianeosis focus groups. Greece, a country that was at the forefront of pro-Europeanism, is now bringing up the rear. Whilst there is still majority support for remaining in the EU and the Eurozone, almost all other indicators (approval of European policies, trust in EU institutions, perception of benefit from Greece’s participation in the EU, etc.) have either declined dramatically or totally collapsed. On the traditional axis of pro-Europeanism and Euroscepticism, Greece is now among the most Eurosceptic EU countries. Disapproval of European institutions and policies is even greater than in Great Britain, a country that is often considered the paradigm of Euroscepticism and recently voted in favour of Brexit.

The critical and decisive difference between Greece and traditionally Eurosceptic countries is the following: Greeks overwhelmingly reject European policies and do not trust European institutions; however, in their vast majority, they still look to Europe and wish to remain within the EU and the Eurozone, with the notable exception of approximately 20% of the population, who wish to exit the Eurozone. The pro-European current, for many historical reasons, is deeply rooted in Greece.

So, first, compared to the 1990s and 2000s, there has been a huge surge of Euroscepticism in Greece and, second, and most importantly, we now have within Greek society the consolidation of a group that is not just Eurosceptic but actually anti-EU, whose strength encompasses of 20% to 25% of population. The great contradiction in Greek society is that while the majority remain unequivocally pro-EU, federalism is more than ever a minority view, and the same citizens who want their country to remain in the Eurozone have a very negative view of Eurozone policies.

What are the characteristics of Euroscepticism in Greece? What are the political affiliations of the citizens that make up this group?

What are the characteristics of Euroscepticism in Greece? What are the political affiliations of the citizens that make up this group?

In Greece there has always existed a segment of the population that was skeptical of the EU. The new phenomenon here is that now this segment is much larger and, above all, it displays a distinct, comprehensive and internally coherent identity. This is a group of people with a shared view of the EU and Greece’s place within it, as well as identical or similar views on the economy, the political system and its main institutions, and on politics. The group bears strong oppositional characteristics and it is “radical” in the sense that it tends to reject anything considered “mainstream”. In reality, I would prefer to term this as the anti-EU “pole” of public opinion since the population segment in question displays a surprising consistency in preference that goes beyond the European issue and extends to the group’s economic preferences, as well as to their opinions on political institutions and politics overall.

Indicatively, as regards political orientation, the composition of this group, based on self-placement on the Left / Right axis is: Far-left: 7%, Left: 37%, Centre-left: 14%, Centre: 12%, Centre-right: 5%, Right: 5%, Far-right: 10%. Even if the centre of gravity of this anti-European current is on the Left, a large part of this group, around 30%, comes from voters who identify as Centre-left,Centrist and Centre-right. It is therefore very much a composite group, with a strong presence of the Left and the radical Right, but which also holds a penetration of the middle ground of the Left / Right axis, in a political field that is traditionally much more moderate and pro-European.

There is a straightforward explanation for the emergence of this group, as it arose due to the outbreak of the crisis and the subsequent policies of austerity and strict supervision through the Memoranda. These two factors (austerity + supervision), interrelated but not identical, are generating an anti-Europeanism that is, for the first time in recent Greek history, consolidated and entrenched. There is always, of course, the issue of how to interpret research data. In terms of making a comparison with the past, the emergence of this group is an important new development, and a major phenomenon. In terms of prolonged austerity policies and repeated instances of conflict between Greece and the European Institutions, perhaps the surprising fact is that the anti-European segment of the population has remained limited to around 20% -25%.

Can this group form the basis for further transformation of the Greek party system?

What we can perceive is the existence of a favorable electoral terrain for the emergence of an anti-EU party. Will a political force, old or new, manage effectively to address this segment of the electorate? So far no party has been able to do it: not Golden Dawn, not the Communist Party, and of course not the smaller parties of the Left. So this current lacks a central and unified political representation. It is electorally fragmented, voting for different parties on election day, thereby creating a void of political representation.

The German political scientist Wolfgang Streeck puts forward the view (Social Democracy´s Last Rounds, 25.2.2016) that capitalism is crushing democracy in Europe, that social democracy has lost its impetus and that it is strange that SYRIZA still harbours illusions about the “European idea”. Would you like to comment?

Nowadays there are three sources of democratic deficit or, more simply, three democratic deficits: a) a democratic deficit (or, rather, a governance deficit) due to the powerful dominance of markets over politics. This deficit is associated with liberal globalization and the overgrowth of a toxic financial sector – and it is in my view the most important one; b) a democratic deficit in the European Union (linked to the specific characteristics of its development); and c) a democratic deficit at the national level, due to the historical weakening of political parties and the crisis of the traditional representative channels. These three democratic deficits are mutually reinforcing. Is capitalism crushing democracy? To a large degree yes, but not only – and not specifically – in Europe, or in the EU or because of the EU. Most developed countries have entered a structural, long-term crisis of political representation.

Does not the EU, however, contribute to the crisis of democracy?

The EU magnifies a phenomenon that is attributable to broader transformations of the political. In principle, the EU, by virtue of its size and through its integration process, could and should decisively contribute in reducing the first and most important democratic deficit, the one caused by the dominance of markets over politics. This would be the greatest and most positive EU contribution to democracy. There have been such aspirations in the past, especially in the pro-Maastricht period. But it does not do so, because Europe has chosen a very different path in its relation with the markets. The upshot is that there is a strong citizens’ perception of lack of democracy within the EU, as the broader structural crisis of political representation is exacerbated by the democratic gaps that are the by-product of the European decision-making framework. The cunning of history has brought back anew the “democracy problem” that appeared to have been resolved in the aftermath of World War II.

How do you evaluate these democratic gaps within the EU?

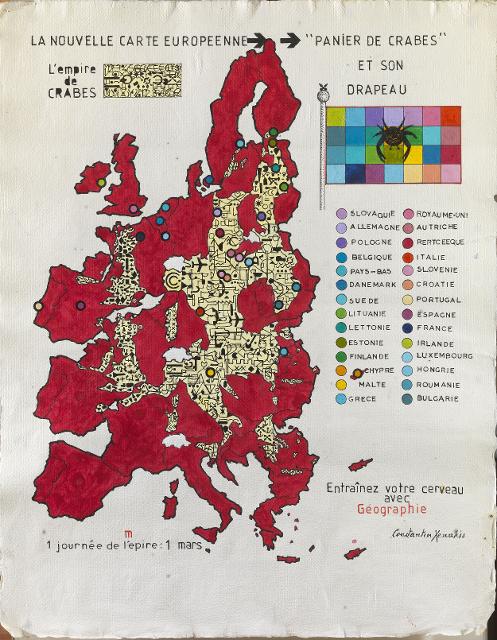

A union of States and peoples is supposed to combine the principle of equal rights for the citizens with the principle of political equality among the member states, as stated in the Treaties. States, however, are unequal by nature and remain agents in search of power for themselves and the citizen-voters they represent. Given that the inter-governmental method prevails within the EU, equality of EU citizens is mediated through the EU member states and therefore through the inequality of power between these states. Thus, there is from the outset a built-in tension between the political equality (i.e. inequality) of states, on the one hand, and the political equality of citizens, on the other – and this despite the rhetorical assurances of the Charter of EU citizens’rights.

There can be no doubt that European citizens are democratically represented in the European Parliament (voters in smaller member states are even overrepresented due to the use of degressive proportionality) and during the past decades one of the most important institutional developments in the EU has been the increase of powers of the European Parliament (despite the still weak position of the EP in the European competence structure). European citizens are also democratically represented, through their national governments, in the European Council, and the European structure is based on the rule of law. In this sense, and only in this sense, the EU is not an “undemocratic system composed of democracies”. In practice, however, combining a democratic mandate and accountability at both the national and the European level is just not possible in the short and medium term.

Let me point out that we shouldn’t too easily and lightly lay all the blame on the EU’s “arrogant elites” for the lack of an effectively democratic and accountable EU. The complexity of EU institutions, the plurality of political centres and the great diversity of interests render the workings of European democracy extremely difficult in any case. In reality, the European democratic deficit is not just, or exclusively, institutional. Nor can it be resolved simply through institutional innovations and corrections. The democratic deficit is structural, i.e. foundational, and strongly related to the tenacious identities of the states that constitute Europe. These strong identities, which are not simply cultural but include fully-fledged state structures, developed democratic institutions, powerful policy legacies and complex communities of interests, must at the same time be protected and integrated into a new system which, to function effectively, must acquire its own identity, cohesion and democratic structuring. This has been, and continues to be, a gigantic undertaking. If a genuine economic and monetary union takes decades (as indicated by the American experience) to become fully fledged, a genuine democratic and accountable Union will take even longer. Minor adjustments might take place but the overall EU democratic deficit is not a solvable problem in the near or not-so-near future. The EU’s experts and politicians who believe that the EU can be democratized in the short or medium term seriously underestimate the complexity of the European “democratic problem”. However noble their intentions may be, their projections represent a classic, an extreme case of wishful thinking.

What do the recent referenda tell us about European democracy?

What do the recent referenda tell us about European democracy?

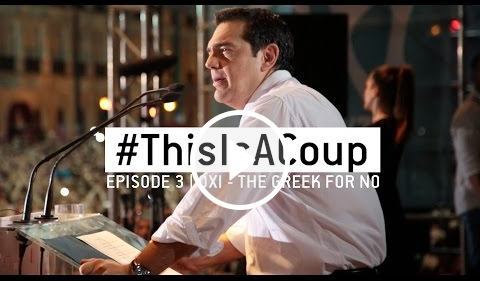

First of all, they tell us what we already knew, i.e. that in the EU a trade-off is often in operation between democracy and efficiency. In the case of Brexit, for example, democracy weakened the EU’s efficiency, reducing its power and influence. Experience with referenda also indicates that there can be a contradiction – sometimes even a frontal clash – between democratic expression in one member-state and democracy in another or others. That is what we witnessed with the Greek referendum of July 2015. Politically, for the EU, ignoring the result of the referendum was a central – and cynical – strategic decision. But what does this mean from the perspective of democratic theory?

In Greece’s case the hashtag “this is a coup” was largely pertinent. But it was not a coup in the sense of a despotic power that violates the will of a people. The democratically elected representatives of more powerful states – in a context of the predominance of intergovernmentalism – did not respect the democratic decision of a weaker nation. One democratic legality did not respect another. The decisions made at the expense of Greek democracy (i.e. the will of Greek citizens) were taken precisely in the name of democracy in other powerful states. Therefore, within the current EU institutional framework conflict between different democratic legitimacies and different popular mandates can easily arise but cannot easily be resolved.

In the present case, rather than a political compromise leading to some kind of “governing together”, what we had was a classic “majoritarian” decision: an instance of “democratic” coercion, even democratic brutality. This coercion – the appellation “coercion”, according to Philip Pettit, is justified “when one is forced to do or accept something because one is threatened with worse” – did not infringe the rules. It did however infringe the tradition of respect for the weaker member-states that had come with the acquis communautaire of preceding decades. Thus, what we had was a combination of the rules (i.e majoritatian decision) and incredible arrogance. In a sense the handling of the Greek case has shown that, contrary to Arend Lijphart‘s classic analysis, consensus systems are not always “kinder and gentler” forms of government. They can become ferocious against anti-mainstream but weak players, not in spite of but because of their very composite system of checks-and-balances. But this cannot be a subject for discussion in the limited space of an interview.

If a trade-off is in operation between democracy and efficiency how does this affect the dynamic of democracy at the EU level?

If a trade-off is in operation between democracy and efficiency how does this affect the dynamic of democracy at the EU level?

In a fragmented European universe of countries, cultures and, most of all, strong and well-developed national state structures, democracy will kill the EU. I weigh my words carefully: Real democracy will dissolve the EU. Real, full democratization will lead to the end of the EU as, in such a case, the trade-off between democracy and efficiency will inevitably be at the detriment of efficiency – and in a disastrous way.

The intermediate and therefore imperfect forms of democracy are the only ones that can match the imperfect model of European construction. However, being imperfect means that they produce what is widely observed: an important double deficit – both in terms of democracy and efficiency, which leads to a growing wave of disaffection and dissatisfaction with the EU.

The abovementioned allow us to understand Europe’s great impasse: in the current stage of European integration (and not that of the 1960s or the 70s) the EU cannot move forward without more democracy. But equally the EU cannot move forward if it becomes truly democratic. It’s a dilemma without a solution. The EU is caught up in a tremendous problem which seems unsolvable.

In this frame, from a realistic and not an ideological point of view, the strategy of those claiming that a great leap towards federalism or further democracy will resolve Europe’s problem suffers from a great lack of realism. Great leaps that cannot be endorsed by national societies are only leaps on paper.

Doesn’t all this affect the behaviour of citizens?

When a considerable proportion of the electorate are convinced that they have been disempowered by an elite and a system largely distant and obscure in its workings, resentment will find ways to express itself. Nevertheless, we should avoid impressionistic descriptions. According to the top experts, it is the performance deficit hypothesis (in the EU but also at the national level) and not the democratic deficit hypothesis that better explains the severe loss of confidence in the EU.

What is your opinion on social democracy and SYRIZA? Do they have illusions vis-à-vis the possibilities of a different politics within the EU?

What is your opinion on social democracy and SYRIZA? Do they have illusions vis-à-vis the possibilities of a different politics within the EU?

There are three things we need to understand here: the institutional question, the centripetal dynamics of European governance and the orientation οf economic policies.

The EU is one of the most original and masterful creations of institutional and political engineering, with a sophisticated and solid institutional apparatus, bordering on the eccentric. Decisions within this “non-state polity” derive from negotiations between the three poles of the institutional triangle (Commission, Council, Parliament) on the one hand and from negotiations between 28 –soon 27- member-states on the other. Although the European Council has become in the process the central institution and key motor of integration, the multiplicity of power centres and the superimposition of decision-making levels has made it possible for the European Court of Justice to assume a significant role in determining the course of integration (which has strengthened the neoliberal character of economic policies to an extent that surpasses the will of national governments).Overall, the EU is a system inherently based on compromise: compromise between different institutional centres, member states, party families. The European political system is therefore a conservative system, not in the sense of a Left-Right divide, but in the sense that it does not easily change such decisions as it has made, and it is allergic to novel policies, whatever they might be. This “conservative” character of Europe’s way of working has not been established by virtue of liberal perversity and will not easily change: it draws its raison d’être from the multinational and multi-State nature of the regime.The European machine cannot function differently. As a result, the EU presents, as George Tsebelis has pointed out, a very high degree of policy stability.

It is also a system that, precisely because it is based on compromise, tends toward the political centre. Europe operates on the basis of lacklustre centrist politics. It also tends to be governed by a kind of grand coalition. Politics, as a clash between meaningful political alternatives, has to a great extent receded –especially as far as economic policy is concerned. The boundaries of the ‘politically possible’ have greatly contracted. Can you imagine a national political system almost perennially governed (in effect) by a grand coalition? With the same major parties co-governing on a quasi-permanent basis? This is what actually happens in the EU. This model of governance, albeit not entirely novel (it has similarities with the power-sharing characteristics of consensus democracies), represents a breakthrough development in the history of the West, and in the history of the party phenomenon. It is almost outside the European tradition. Τhis is the reality, even if this operating model is contrary to the electoral interests of the moderate parties themselves, both on the centre-left and on the centre-right. But constant compromise and convergence towards the political centre goes against the grain of both left and right radicalism, of any radicalism for that matter. Radicalism naturally seeks grand changes, right here and right now if possible.

Apart from the institutional and governance aspects, consideration must also be given to a third factor, that of policies. For a number of decades now the economic policies adopted by the EU have been basically (though not exclusively) neoliberal in inspiration. As a consequence, given that, for the reasons outlined above, decisions cannot easily be changed, the EU in effect functions as a strategic barrier thwarting the adoption of alternative policies championed by forces outside the mainstream. The same applies for Social Democrats, who have not been able to promote a different economic policy model within the EU. Furthermore, the entry of Eastern European countries into the European family has strengthened the conservatism, both institutional and economic, of the entire regime.

Institutional conservatism (1); centrist governance (2); and the predominance of neoliberal economic policies (3), make the EU the epicentre of a new Western economic conservatism. Germany and its allies are the leading group of countries supporting this evolution of European integration. France, the European Commission, the European Court of Justice and the ECB are also crucial to the system working as it does. Unilateral attacks on Germany are therefore partly exaggerated: they underrate the institutional infrastructure underpinning the EU and downplay the fact that complex systems have effects that transcend the will of the participating actors (member states, institutions or party families). The EU places constraints on everyone, including Germany, including the elites: on everyone but not to the same degree. To sum up, the EU, institutionally, and on the basis of its policies, operates more as a trap than as a source of hope for the Left. This is as true for Social Democracy as it is for the radical Left. No realistic reading of the situation leaves room for illusions in that regard.

The only way for more Leftist policies to be implemented within the existing EU would be through a simultaneous change of economic policy in several EU countries, and above all in three or four important ones (first and foremost Germany and France, but also Italy, Spain etc.). Such a simultaneous change is not very likely, but even if it did occur, it would require a very broad inter-institutional agreement. Thus, it would be very difficult for it not to get stuck at some point in the process. The overall context (segmented powers, high institutional hurdles for any policy reorientation, jurisdictional acquis, the small EU budget, and, last but not least, intra-Left divisions) makes the social-democratic reorientation of the EU very difficult to implement.

At the same time, although those who consider a change in orientation impossible, (because the EU is “an extreme case of a multiple-veto system” [Fritz Schapf]), are not wrong in their basic argument, they do overlook the institutional change and the shift in the balance of forces that has indeed occurred within the EU. Today in the EU there is a dominant state, something that was not the case in the past. Furthermore, the EU regime has become less consensual (or more majoritarian), which should in abstracto make policy reorientation easier. Permit me, then, to discuss an entirely abstract working hypothesis. In the future, if a social-democratic government in Germany really and decisively wanted to change European economic policy, then many of the veto points of this multiple-veto system would never be activated. Change or continuation of the present economic policy is very dependent on Germany and the power balance between three or four large states. This takes us back, of course, to the preceding discussion on European democracy and the fundamental inequality of the member states. Waiting for the Germans? Is that in the long term a mutually acceptable partnership relationship? It also takes us back to the historical conservatism of Germany, including the greater part of the German Left (the SPD, for all its Marxism and its rhetorical radicalism, was a bulwark of conservatism during the period of the Second International). But it also introduces a note of relativism into the institutional system debate. Institutions are not all-powerful. Neither change nor stagnation can be explained through institutions without any reference to actors. Institutions are obstacles or weapons: they do not generate policies by themselves.

So were SYRIZA’s policies condemned to failure from the outset?

So were SYRIZA’s policies condemned to failure from the outset?

To a great extent yes. SYRIZA has quite a few populist features, but its proposed economic policy in the run-up to the January 2015 elections, the famous “Thessaloniki Programme,” was nonetheless a typical social democratic programme, and actually quite a moderate one (a mildly expansionary policy, with mild relaxation of monitoring and conditionalities).

Ultimately, what SYRIZA asked for in early February 2015 was a quite gradual and controlled transition from the “Troika regime” and brutal austerity to a greater economic autonomy and a reasoned growth policy. At the time that the negotiations officially began, the objectives concerning restructuring of the debt (but also the goal of an international conference on debt) had, perhaps temporarily or tactically, already been abandoned. After five years of sharp recession, what it was proposing was a very prudent economic turn.

This was not a radical policy. Its radicalism was primarily discursive. But a policy of this kind was outside the EU’s policy framework and by that – and only that – criterion, it could be considered radical. The European institutions did indeed refuse to accept SYRIZA’s proposals (which in their final formulation, to reiterate, were a much more moderate version of the “Thessaloniki Programme”) as the basis for a new agreement. This mild deviation from the European mainstream proved unviable and unacceptable. Of course, the limited bargaining power of a bankrupt country with a longstanding bad reputation, not to mention the amateurishness of SYRIZA, the grave lack of understanding of EU mechanisms, the absence of concrete and easily-communicable negotiating foci, the fanfares coming from ministers of SYRIZA, all this contributed to the final outcome. But whatever the weaknesses of the Greek side, a striking feature of the negotiation was both the incapacity and the lack of will of the European technical and political bodies to innovate even a little, faced with such a new phenomenon as SYRIZA. The rigidness in question expressed a policy style, an entrenched behaviour, and not any kind of expertise. It was part of the in-house culture, transforming the EU into a machine that is largely the prisoner of its own automatisms. I nevertheless repeat that if, in the place of Greece’s Leftist government, there had been a Leftist government of a powerful European state, then, I assume, European technical and political bodies would have been more flexible and sought a compromise.

If the overall context is negative, why do the Social Democrats and the majority of the radical Left persist in their European strategy?

It’s not just the economy that counts. The EU is strong precisely because it proposes for national states a framework that involves more than the economy. The pro-European Left did not become pro-European just by mistake; there were substantial national interests that drove a number of countries to join first the European Community and then the EU. Apart from the initial aspiration of leaving behind divisions that led to World War I and World War II, what motivated them was national economic interests, cultural affinities, important geopolitical goals, and, of course, factors linked to globalization; size matters when national states, especially small ones, are weaker than ever. Count how many small states belong to the EU.

Let us consider an example. The great irony of the radical Left’s European policy is that they gradually accepted European integration just as the latter was acquiring increasingly neoliberal characteristics. The transformation of Europe, after the second half of the 1980s, into a powerful, heavyweight political machine induced nation states to seek inclusion in the EU, and parties on the Left to give “critical support” to this process, in order to avoid political isolation, among other reasons.

The EU provides nation states with a kind of security and the opportunity, real or imagined, for greater political leverage. Security is a multi-layered concept: it includes geopolitical security, economic security, and, for some countries, democratic security. Political and geopolitical factors have led states and their citizens (from France and Germany to Finland, Greece, Cyprus and the Eastern countries) to wish to be part of the EU, or to remain in the EU. For the economically weak member countries of the Eurozone in particular, the cost of exiting, or, to be more precise, the short-term cost of transition to a national currency, could also prove heavy. If we view the EU strictly in economic terms, we will not understand anything about its power and weaknesses. National populations, as bearers of historical memory, understand EU membership as something more complex than what is evident from the analyses of economists, whether pro- or anti-EU. For example, in Eastern Europe, confidence in the EU and support for membership have a strong security and identity component.

None of the foregoing changes the fundamental fact that the EU destabilizes all strategic options that have dominated the history of the Left, whether social-democratic or radical. The structure of political opportunities for the parties of the Left – however significant they might be in the domestic political arena – has become, because of the EU, much more unfavourable than it was in the past. This, in the long term, can only serve to reinforce Euroscepticism and the anti-euro tendencies within the Left, particularly the radical Left. In any case, the “in or out” dilemma, whichever side one opts for, involves no optimal solutions, only less bad ones. Besides, the “good” solution may be different for each country.

What do you think are the prospects for the Radical Left?

What do you think are the prospects for the Radical Left?

The claims for social justice and more democracy are very strong and more timely than ever. But perceptions and opinions based on neoliberal core values and ideas are equally strong. We often see ideas from rival ideologies being adopted by the same person, cutting across class and social boundaries. This coexistence of antithetical ideas has its origins in the transformation of contemporary capitalism. Nevertheless, two major developments – on the one hand, the humiliating collapse of really-existing socialism and, on the other, the crisis of Keynesian politics – brought about the great strategic retreat of Leftist ideology. This became evident in the last quarter of the 20th century, together with the triumph of the deregulation of the markets. Thus, within modern societies, both the ‘big Utopia’ and the model for improvement and humanization of capitalist society have been defeated. In reality, today, neither the radical version of Leftist change nor the moderate social-democratic version are being articulated politically or culturally.

While citizens tend to reject mainstream policies, they remain at the same time skeptical towards alternative policy proposals. I think, or perhaps sense, that citizens fear the uncertainty that is entailed in alternative proposals. The major obstacles that the predominance of the markets poses for any project of changing the economic paradigm engender a fear of uncontrollable consequences. Strategies of social transformation, whether radical or reformist, appear unconvincing, not to mention dangerous. They create uncertainty and insecurity in all European populations.

The example of Greece is, in my view, representative of the “electoral economy” of fear. The proposal of exiting the Eurozone, whatever its economic rationality, was not electorally attractive as the average voter does not easily choose a decline in his living standards (even though Greece has lost more than 25% of its GDP !) for the prospect of a future medium term improvement. Many left-wing analysts in Europe have not realized the great fear of uncontrollable consequences and, from this perspective, the limits of radicalisation in the Greek population.

Policies of social transformation have always evoked fear ….

Hyper-globalization in finance and trade and, in particular, the overgrowth of the financial sector in conditions of strong economic internationalization constitute a crucial difference in comparison with the past. Financial actors are flexible, fast and impersonal. They act at the supranational and supralocal level and are therefore not bound by any national or local culture of social cohesion.

In this new context, the choices of electorates, when unfavorable to the profit strategies of the financial sector, are not so great an impediment as in the past. Bank and financial investment lobbies take on board whatever economic cost is involved and rapidly move their capital elsewhere. Protests, social movements or even uprisings don’t cost them very much, either. The industrial sector too, given the extremely strong competition from Asian countries, has greater bargaining power vis-à-vis governments. The power οf the Left, therefore, holds no great threat to the world of capital, and particularly the financial cluster, in the way that it frightened capitalists in the past. The necessity for the financial sector to converse with unfriendly governments is much weaker than it was in the framework of the nation-state. As a result, both the “partisan path to politics” and the “movement path to politics” (to cite two expressions of Leo Panitch) have been weakened as tools for democratic sovereignty. The dynamic of markets against politics today is stronger than the dynamic of politics against markets. Both dynamics remain active, but the former has imposed its supremacy over the latter.

Against this background the power of “global forces”, however defined, seems oversized and irrational. They are in a position to punish whole societies, their national bourgeoisies, the elites, the middle class, along with the poor and lowly of a given social formation. The citizens, however inchoately, sense this. Parties like SYRIZA (before the compromise of July 2015), Podemos or Left populist parties in Latin America are therefore seen as portending great economic uncertainty, despite being far more moderate than the parties of historical communism. Uncertainty – or, more precisely, fear of uncertainty, fear of the unknown, fear of punishment from the markets – is the real force behind the vitality of the status quo.

The electoral rise of the radical Left, which some have been expecting (but which in any case is not general), may continue in some countries, if only because citizen frustration with mainstream political forces is running extremely high. Risk-takers have increased among voters, as we saw in Greece, in Great Britain with Brexit and in Spain with Podemos. But improved electoral performance is one thing; implementing policies of social transformation is quite another.

You have written that “the stabilization of SYRIZA as a big central party on the Left of the political spectrum passes through the formation of a strong reformist profile and the implementation of effective policies”. What do you think of SYRIZA’s trajectory so far in this respect? Can SYRIZA promote Leftist / progressive reforms? As far as social policy is concerned, can it defend the poor / the losers from the crisis?

The framework of the 3rd Memorandum signed by SYRIZA is too stifling even for the simple implementation of more moderate austerity policies. SYRIZA is trying to manage something that is, if not impossible, to say the least very difficult. To this it should be added that SYRIZA was without governmental experience, and the quality of its political personnel was – and still is – mediocre, despite certain exceptions. This is one aspect. The second is as follows: It is not by chance that SYRIZA has won a number of elections. There is a profound rejection of the old political personnel, epitomized in the vote for SYRIZA. Even today, when many people are extremely frustrated by the political U-turn, the inefficiency and the tacticism of its leadership, SYRIZA still stands for the new as against the old. This is the interesting paradox. The stabilization of SYRIZA as a big central (not centrist) party on the Left presupposes the formation of a powerful reformist profile and the implementation of left-wing reforms, which are the only means by which SYRIZA might in the long term be able to hold together its particularly composite electoral base. So the important thing for SYRIZA is not to win the next elections, but to persist over time as a central political force in Greek society. This is not something of which one can be certain, but it is not so very difficult either. But the spiritual and strategic horizon of SYRIZA’s leadership seems to a significant degree to extend no further than the next election. Tacticism is what predominates. This is an unfortunate development, particularly if one has in mind the country’s huge problems. Short-termism is ideologically and politically self-defeating.

What might be the big reforms that will really signal that this country has had a Left government that made an impact?

What might be the big reforms that will really signal that this country has had a Left government that made an impact?

It is not my role to make policy proposals or play the political consultant. But I will give one example. Taking into account the lack of economic resources, I would say with certainty that the two major reforms that should be implemented are the establishment of a cadastral system and the radical improvement of tax administration and the tax system. These two reforms have been overdue since the 19th century. Can the SYRIZA government promote them effectively? My response is that if a Left party does not implement these reforms, then who will? And if that Left party does not implement them, what justification can it have for expecting people to vote for it? We had the same problem with PASOK: it was a scandal to have the Left electorally so dominant (the Left in a broader sense) in Greece, and yet to have this degree of tax avoidance, tax evasion and evasion of social security contributions. A good tax system is a modernizing act as it enables the economy to function with clear-cut rules, facilitating economic growth. It is also a crucial budgetary reform because the Greek debt was the product of thirty years of budget deficits driven by a proportionately low level of tax receipts. This was the “fatal deficit”. It is at the same time a left-wing reform, not only because it is in accordance with the traditions of the European Left and the workers’ movement, but above all because the beneficiaries will be the wage earners in the private and public sector; that is, the groups that have for decades borne the greater part of the tax burden. Of course Greece is a country of small businesses, with a high proportion of self-employed people in the workforce. It is the breeding ground par excellence for tax evasion and tax avoidance. And the transformation of a long-standing vicious circle into a virtuous circle requires, much more than in the case of other countries, tremendous resources and a great mobilization of expertise – without immediately visible results and without immediate political benefit. It is no coincidence that in the Greece of crisis the governments, all the governments of the period from 2010 to 2015, with the complicity of the institutions and the Troika, instead of concentrating their efforts on a decisive and definitive reform of tax administration, allowed – like Grouchy at the Battle of Waterloo (to paraphrase Stefan Zweig) – the greater part of the available forces and resources “to wander about aimlessly far from the battlefield”.

Faced with the huge difficulty of solving the problem, the SYRIZA government seems to be behaving in an inefficient way. It is, to be fair, trying to broaden the tax base. It has increased taxation of the usual suspects of tax evasion and legal tax avoidance (big businesses, small businesses, liberal professions, farmers), but it has done so amateurishly, harshly, committing new acts of injustice.

I’m sorry to say this, but it should do something more systematic, more ambitious, more imposing, more stable, more long-term. Let us not forget that Greece is probably the worst country in Western Europe for wage earners, who have been called upon, through taxation, to close the budget gaps left by the outrageous tax evasion of most enterprises, large and small, and liberal professionals.

And what about the Parallel Programme?

What the government calls the Parallel Programme, meaning policies that could protect the socioeconomic strata who are worst hit by the crisis and have found themselves outside the economic system –i.e. the very poor, the excluded, the unemployed – is a social imperative. SYRIZA has had some minor but significant successes with this programme. But it lacks the resources and necessary expertise to fully design and implement such a program. And neither does the state have the appropriate mechanisms or expertise to locate and determine who is really in need. It would be good for those who have undervalued the great importance of successful state building – and this is something that applies for virtually all the Greek Left, social-democratic and radical alike – to rethink their theories and their incredible ideological naiveté. In any case, I doubt that the Parallel Programme is going to achieve its objectives.

The cultural dualism schema (proposed by Nikiforos Diamandouros in the 90s) posits a distance between Greece and the European / Western modernity. Is Greek society and the Greek state due for a rethink in the light of the crisis?

The cultural dualism schema (proposed by Nikiforos Diamandouros in the 90s) posits a distance between Greece and the European / Western modernity. Is Greek society and the Greek state due for a rethink in the light of the crisis?

The Dianeosis survey highlights something very important: the political and value cleavages within Greek society are distinctly European, and specifically, Western European. The prevalent divides (economic liberalism / economic interventionism, cultural liberalism / cultural conservatism, pro-Europeanism / Euroscepticism) against the background of the still dominant Left / Right cleavage, indicate that Greek society fully belongs to what has been named political modernity, in the Western European sense of the term, as these divisions in Greece are better structured and more developed than in Eastern European countries.

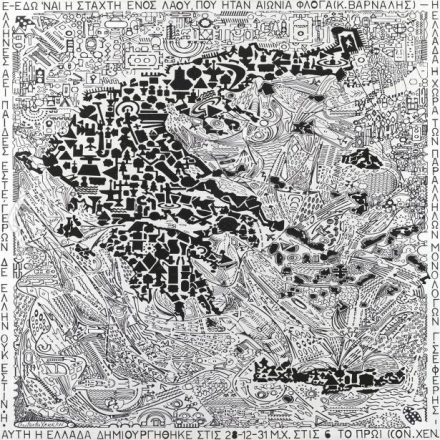

Besides, the reason that Greece has been in the spotlight of international public opinion and media debate for so many years (as has happened many times in the past), is of course not due, or at least not mainly due, to its small economic size. It is due primarily to its geopolitical position but also to another factor that is often overlooked: Greece has not just conversed diplomatically with the West, but has also produced “Western” events.

Greece has exerted influence and touched ideologically (and emotionally) Europe and the world through the events it produced. From the 1821-30 War of Independence (the first uprising leading to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire) to the 1946-49 Civil War (the first battle of the Cold War) and the democratization of 1974 that inaugurated the third great wave of democratization in the West, and so forth. Moreover, given that Greece’s political cleavages are of a Western type, understanding them is very easy for a Western observer.

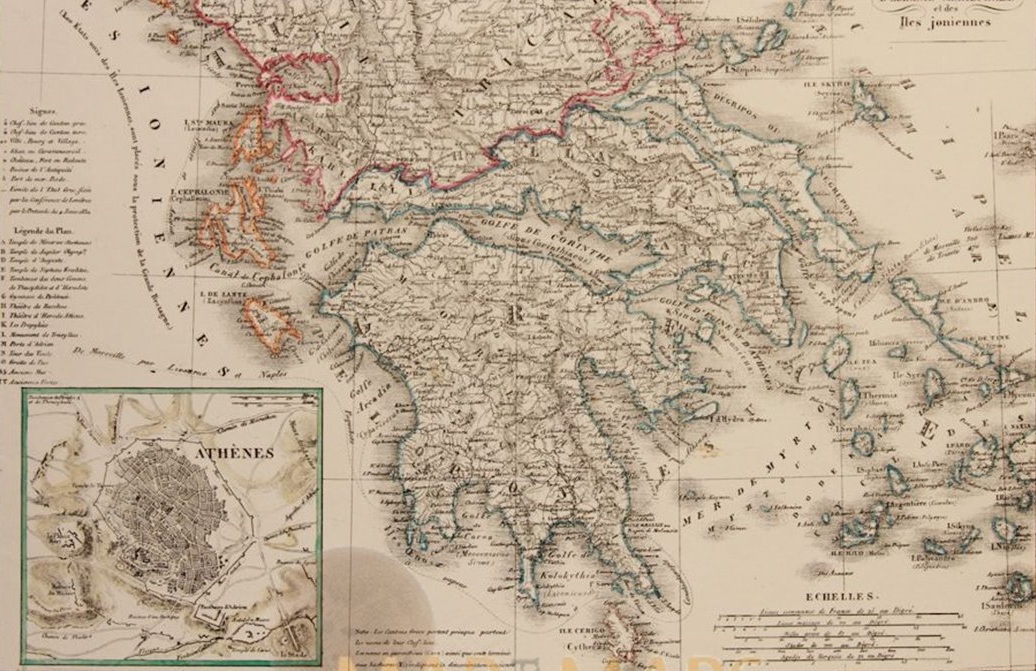

Greece was founded, for reasons that cannot be analysed here, by the crème de la crème, the very best elements of the Balkan elite. For the greatest part of the history of the modern Greek state (founded in the early 1830s) parliamentarism was the main form of the polity. Simultaneously with France and Switzerland, the Greek state was a pioneer in institutionalizing universal suffrage for men. Well-functioning parliamentary institutions were in place as early as 1875 (such a political development was at that time rare for Western European countries). Almost the entire male population was extensively involved in the electoral process, and from 1880 onwards we witnessed the stabilization of a very functional, for that time, two-party system. According to Nikos Alivizatos, Professor of Constitutional Law, at the turn of the 20th century, Greece “… counted among the close circle of constitutionally developed countries in Europe, while it exceeded the Balkans to a great extent. This was due not only to the quality of the electoral procedures and the proper functioning of parliamentarism but also to the respect for individual freedoms”. The lower strata were included in the electoral game and, last but not least, social inequalities were limited.

However, though political modernization, a historically small degree of inequality and, to some extent, cultural modernization, are important achievements, Greece always lagged in economic modernization and state building. Up to a point I agree with the analysis of Stathis Kalyvas, according to which, seen from a long-term perspective, Greece is a success story. A success story which, to be sure, has been accompanied by great crises, profound failures and a culture including a great many repellent traits. The individualism, the family-centred amorality, the clientelistic mentality, the interest groups operating in a narrow corporatist spirit and, overall, the great distance between “rules in form” and “rules in use”, have all contributed to creating a society in which, notwithstanding the absence of extreme inequalities, the sentiment of injustice is predominant. All in all Greece is a country of great contradictions. Greece resembles, I would say, a strange European province that has all the problems and infirmities of a province, while at the same time it has an educated population and, often, exceptional cosmopolitan elites that make it distinctively “non-provincial.” Greece has great difficulties managing this explosive contradiction along with its ambiguous identification with modernity. Hence the huge successes and the terrible crises that characterize its history

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi and Nikolas Nenedakis