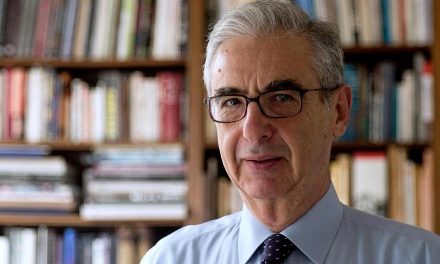

Stella Belia is a Greek activist for LGBT rights. She is the President of Rainbow Families organization, which represents Greek families of same sex parents and their children and strives for equal opportunity policies. She works as a kindergarten teacher in Athens and raises five children with her partner.

The introduction of a civil partnership law in Greece (December 2015) brought to the forefront the question of LGBT rights in the Greek society, and it is in this framework that Rethinking Greece* asked Stella Belia to answer questions on the current status of LGBT people in Greece, the human rights agenda in times of pauperization and crisis, the perception of homosexuality in Greek public opinion as well as possible conflicts between more traditional values and the liberal mindset that permeates the international LGBT agenda.

The recent enactment, with a broad parliamentary majority, of the of same-sex partnership law is regarded as an important milestone in the history of LGBT claims in Greece. How do you assess this development?

This law gave many people the necessary breathing space to finally talk openly about their sexual orientation, to organize their life and to solve many everyday problems. Yesterday I saw a gay couple that had been closeted all their lives sign a civil partnership contract and submit it to the municipality of a provincial town. After that their life will substantially improve, and this has great significance.

On the other hand, the fact that our children were left behind (the right of gay couples to adopt was not included in the new law) was a big disappointment for us. Up until the last minute we believed that the legislators would make a point of responding to the needs of the most vulnerable group of citizens: the children. Unfortunately it was not so.

We must understand that we are not talking about hypothetical persons. We are talking about real people, living next to us. I think that, although this law will not result in a huge influx of people signing up for civil partnerships, it will somehow educate society to a reality that otherwise would be kept hidden or invisible, as many people turn a blind eye to it.  European societies are on a track of granting universal rights regardless of sexual orientation. Do you believe that this battle has been largely won, or are you afraid that a political realignment in Europe could bring forth forces that might threaten those gains?

European societies are on a track of granting universal rights regardless of sexual orientation. Do you believe that this battle has been largely won, or are you afraid that a political realignment in Europe could bring forth forces that might threaten those gains?

Many rights that we thought were established and inalienable -e.g. labor rights- lose their non-negotiable character and are put back on the table to be re-negotiated or repealed. The same goes for human rights: the current economic and political circumstances favor the rise of conservative parties and groups, which to a large extent derive their political power from people who previously upheld liberal ideologies. This is what happened in our country, where those who support the Golden Dawn party come mostly from the voters of New Democracy, the party “closer” to their conservatism.

This means that we could face situations where countries like France, which have made considerable progress in equal rights, plummet to racist and homophobic policies, in case of an election victory for Marie Le Pen.

To what extent do you think the economic crisis and the pauperization of the Greek population has affected the debate on the so-called human rights agenda?

Consider how human needs are classified (e.g. on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs): at the base we find the need for survival (food, water, etc.) and on the next step we find safety concerns: physical safety, labor security, resources, health, property, etc. With the economic crisis there is an increasing number of people who cannot satisfy even the needs at the base of the pyramid, like eating, and an even greater number of people who may barely meet those basic needs, but cannot meet the needs on the next level, because of issues like unemployment, no access to healthcare, inability to pay their mortgage etc.

It is therefore very difficult for a person dealing with any of the above situations to think about the remaining levels at the top of the pyramid, like social acceptance, self-esteem and self-realization. How do we talk to people about gay rights when they are in such dire situations? On the other hand, the duty of every well-governed state is to try and create the necessary conditions so that no citizen can be discriminated against for something like their sexual orientation. The pauperization of Greek society should not prevent the state from ensuring equal rights for all citizens.  What role could public education play in cultivating certain attitudes and social perceptions on LGBT issues? What are the specific actions that the State could take? What are the obstacles placed, and by whom, in this course of changing Greek education?

What role could public education play in cultivating certain attitudes and social perceptions on LGBT issues? What are the specific actions that the State could take? What are the obstacles placed, and by whom, in this course of changing Greek education?

Firstly, Greek education suffers an obvious deficit: the Ministry of Education in our country – despite the various names it has been given over the years, such as Ministry of Culture, of Sports, of Life-long Learning, of Research etc – has always had attached to its name the term “Religious Affairs”. The fact that a secular policy area like education is part and parcel of religion brings to mind theocratic power structures. It also poses a significant obstacle to promoting changes in the education process towards inclusiveness and the dismantling of LGBT-related stereotypes.

Let me use the example of LGBT parents’ families. Our children, ever since they enter school, starting from kindergarten, don’t see in their school books any family resembling their own families. Besides, in the ranks of the teachers, there is a widespread perception, overtly expressed, of the heteronormative family as the “best” family and all other types of family structure are considered less than, inferior, deficient etc. As a result, our children are forced to keep their family reality out of their school’s door and they join it again only after they school.

It’s been a while now, since we – the organization of Rainbow Families – undertook the task to change this: we are trying to engage University departments that offer teaching degrees, so that future teachers are better informed on LGBT issues. We are also producing material to be used by educators who wish to depict the variety of different family structures. We are currently working on an Alphabet to teach phonology to toddlers and children of primary school ages: the text includes pictures and references to many possible family structures, so that all children can see in it a family that looks like their own family. Moreover, we keep broaching this issue in European conferences. Last but not least, we are in contact with organizations abroad, such as Schools Out, with a view to gaining from their vast experience on how to push things forward towards an all-inclusive school that gives all children space to develop and thrive.  During the recent conference held by “Rainbow Families” (“Love Creates Families,” 13-14.2.2016), the word “fear” was often heard from young people living in the Greek countryside. Do you think that there is a two tier Greece as far LGBT issues are concerned, on a center / periphery axis?

During the recent conference held by “Rainbow Families” (“Love Creates Families,” 13-14.2.2016), the word “fear” was often heard from young people living in the Greek countryside. Do you think that there is a two tier Greece as far LGBT issues are concerned, on a center / periphery axis?

I am citing an excerpt from the published life story of a gay guy living in the Greek province, specifically in Lappa, a village very close to Patras: “… I’ve been beaten several times. They took me out to woods; they stole my clothes and left me naked. They started spitting on me, kicking and laughing at me. They keep hanging out of my house and scream “Set the fag’s house on fire!”. I have suffered a lot. And the worst part is, my mother is currently severely ill, with a very serious disease, and they don’t even respect my need to take her out for a walk. They will attack me in front of her”.

This case of abuse was heard by a court, but the Greek justice system, instead of convicting the assailants, based its decision on the allegation that this guy and his aged mother were “provocative”. What else can I add? It is without a doubt that there’s a big difference between living in the anonymous crowd of a big city and living in a small village. Needless to say, the latter is way more difficult.

In response to the increasing migratory flows in Europe, some express fears that the “European way of life” will be “undermined” because of the influx of people of other religions, with different customs and values. Does this debate pertain to LGBT issues?

The refugee crisis is a matter that concerns everyone and everything. This is one of the biggest humanitarian crises in history since the two World Wars. Surely these people come from countries with different norms but what does this mean? People usually choose to keep those habits and customs that do not undermine their new life. When our own people migrated to Germany, U.S.A. or Australia, the traditions they observed were the celebrations of big holidays and especially their fun parts, like the spit lamb on Easter, and not the traditions like the “vendetta” between families.

Now, with respect to the “European way of life”, I don’t see us experiencing this way of life in Greece: Take a look at some high ranking church officials that adopt deeply negative stereotypes about gay people and demonstrate strong resistance against what they perceive as a “European way of life.” Just remember a prominent Greek politician’s provocative statement about Luxembourg’s Prime Minister. This aspect of Europe, therefore, is not yet firmly established in our country.

In some countries LGBT issues figure prominently in the political agenda, and political parties communicate their positions on these issues to the citizens, just as they do on any other policy issue. Is that the case in Greece?

I think this gradually happening in Greece. So far we’ve been a weak, easily neglected minority, with practically no political influence. Since the vast majority of LGBT people are not openly out, politicians for the most part thought that defending our rights wouldn’t bring more votes, or even worse, could backfire. I can sense a change in the climate now, as everybody understands that we and our allies are acquiring political clout, in terms of influence and number of votes. I believe that soon this is going to lead to serious changes in several political parties with regards to the way they deal with our community’s claims.

*Interview by Alkis Delantonis & Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: LGBT