Johanna Hanink is Associate Professor of Classics at Brown University, US. Her work focuses on ancient theater and performance, the cultural life of classical Athens, and the idea of the “Greek miracle.” She is a regular columnist for the online magazine Eidolon: a modern way to write about the ancient world.

In her latest book “The Classical Debt: Greek Antiquity in an Era of Austerity“, recently published with Harvard University Press, she “investigates our abiding desire to view Greece through the lens of the ancient past” and “explores how Western fantasies of classical antiquity have created a particularly fraught relationship between the European West and the country of Greece, especially in the context of Greece’s recent “tale of two crises.”

Professor Hanink spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the notion of cultural indebtedness and its political character, classicists and their responsibility to dissuade people from “dwelling too much on Greek antiquity”, the imagined concept of the “original” Athenian democracy and the long history of recorded disappointment in “modern” Greeks.

She stresses that “fantasies of antiquity exerted such a strong influence on the formation and even the “branding” of the modern Greek state that Western media almost has no other way of understanding Greece at all,” concluding that she would like to see work on “narrative economics” to expain how has the narrative of Greek cultural/civilizational decline affected policy, and how has that narrative affected how the world has perceived Greece and its economy, and what further narratives (about the Greeks’ work ethic, spending habits and so on) about the economy have taken root:

You have noted that references in the international media to the classical Greek past are often deployed in a way that is misinformed, paternalistic, and condescending. Can classicists say anything meaningful about modern Greece and its economy?

You have noted that references in the international media to the classical Greek past are often deployed in a way that is misinformed, paternalistic, and condescending. Can classicists say anything meaningful about modern Greece and its economy?

Not particularly. As a classicist who’s just written a book mostly about modern Greece—and who can write about modern Greece these days without writing about the economy?—I realize that probably sounds hypocritical.

Let me clarify: I don’t think that classicists can say much that’s meaningful, or “expert”, about the technicalities of the modern Greek economy. In Greece these days they say that everyone’s become an amateur economist. Given the delicate politics involved, though, I think classicists should not pretend that patchy knowledge about ancient Greece translates into real understanding of what’s happening in Greece today.

On the other hand, classicists who are aware of the history of their discipline—a history very much intertwined with the history of colonialism and of the modern Greek state—have useful second-order interventions to make. What I mean is that those classicists might have something to say about why the story of the Greek economy is so often portrayed as it is in Western media, as, say, a tragic (or even comic) plot from an ancient Athenian play. Classicists should be the ones who cry foul when calls are issued for Greeks to read up on Stoicism. If we are complicit in this kind of media coverage, it will only prove that the discipline is (still) out of touch and colonialist.

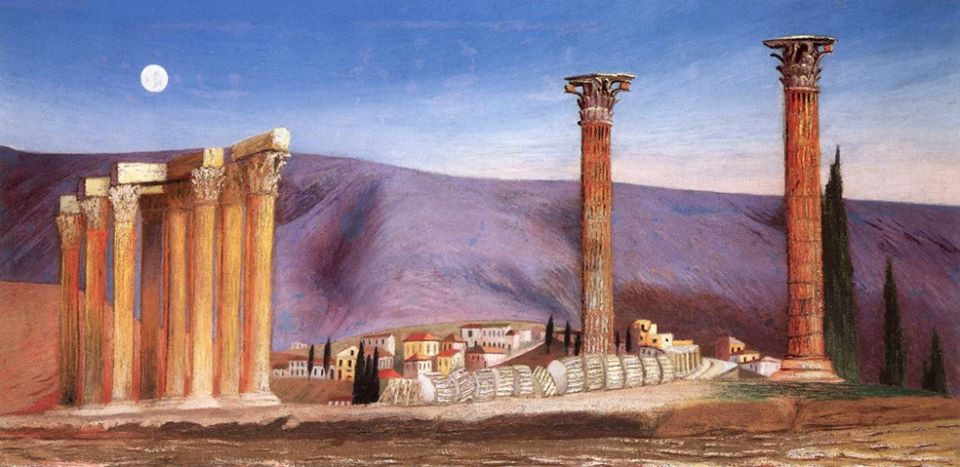

Ruins of the Jupiter Temple in Athens, 1904, by Tivadar Kosztka Csontvary

So when it comes to the Greek debt crisis classicists have a counter-intuitive responsibility: they should be dissuading people from dwelling too much on Greek antiquity. Ancient Greece in this context is a distraction that ranges from counter-productive to harmful.

In a recent “Europe Holidays “article in the FT (A short break in ancient Athens May 11, 2017) the author notes that “There is something epic about recent events that seems to encourage reflection on the classical past…” Would you like to comment?

A few months ago, Neville Morley wrote a great blog post called “Welcome to the Toga Party,” about all the media think pieces that have lately brought ancient Rome to bear on British and American politics. He made a very good point: these ancient analogies serve to “present our current historical predicament in more elevated terms”. By comparing Trump to Nero, or citing the course of Roman history as proof that the end of the American Republic is nigh, we make our own era seem more “epic” and momentous (or as Morley puts it, we imply that “We are living in a time of Great Men and Terrible Villainy and Heroic Deeds and Grand Gestures!”).

There’s certainly an element of that kind of thinking on view in the FT article (which I actually found very irritating). But there’s something more to the case of the Greek crisis and all the ancient analogies it’s inspired. Fantasies of antiquity exerted such a strong influence on the formation and even the “branding” of the modern Greek state that Western media almost has no other way of understanding Greece at all. Ancient Greece has been baked into the national cake. George Zarkadakis took an extreme view when he wrote, in a Washington Post op-ed, that “Modern Greece was thus invented as a backdrop to contemporary European art and imagination, a historical precursor of many Disneylands to come.” But I think there’s something to that observation, something that means that, in Greece, “recent events” will always seem “to encourage reflection on the classical past.”

In The Classical Debt, you note that the Greek crisis / Grexit discourse put forward key questions: “Can Europe claim the legacy of ancient Greece if the country of Greece is not part of Europe? To what extent do Greeks get to claim that legacy as their own? How much does the Western world continue to owe the Greek people for things their ancestors did thousands of years ago?” Can you give us brief answers to these questions?

These questions are the bread and butter of the book. I don’t think there’s any real answer to them, and I’ve been criticized for not showing my hand on issues such as the repatriation of the Parthenon Marbles currently held in the British Museum. Everyone’s got an opinion about that kind of thing (and I do too), but very few people have a new opinion. What’s new about this book, I think, is its examination of how, when, and why all of these questions and controversies came to be formulated.

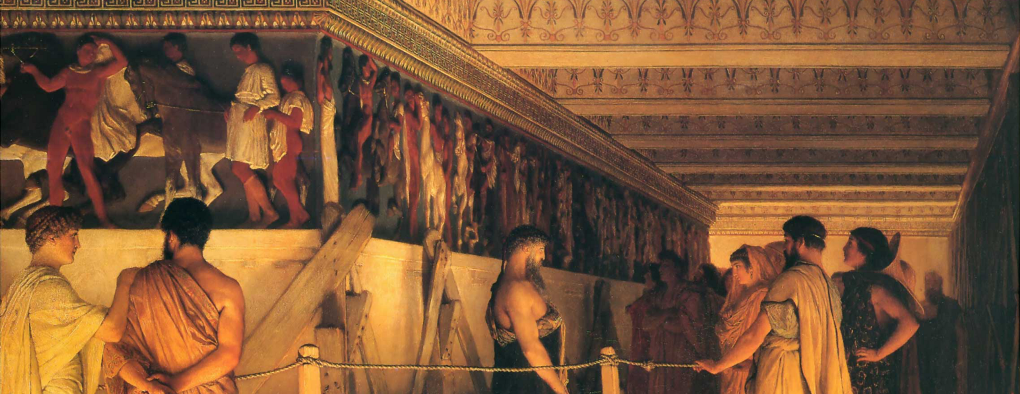

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, 1868, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

I do nevertheless suggest that this notion of cultural indebtedness—a notion that is very prominent in the Anglo-American world— is unproductive. If we are especially indebted to Greece, are there then cultures to which we owe nothing—or worse, are there cultures who owe “us”?

To me, what’s most interesting about these questions is how political and polarizing they have been. They underpin even bigger questions about the nature and even the very existence of the West. When the West wants to talk about itself, after all, it often starts with Greece.

You also note that admiration of ancient Greece is a stronger bond among Western nations than “fragile political coalitions such as the EU and NATO.” Classics were once the foundation of a “gentleman’s education,” what is their relevance today? What brought you to the study of the Greek world?

The story of how I came to study classics is only interesting because it’s so typical. I started Latin when I was eleven, then took two semesters of university Greek in high school. When I got college, at the University of Michigan, I couldn’t decide between majoring in classics and economics. I remember sitting in the office of an extraordinary professor there—H.D. Cameron—who told me that classics departments (compared to economics ones) are small and close knit, and if I chose classics I’d always have an academic home.

I was lucky because at Michigan, Modern Greek Studies is a really integral part of the Department of Classics. During my last year, I took Modern Greek History course with Artemis Leontis. That was the course that first introduced me to, among other people and things, George Seferis and Melina Mercouri. I was completely gripped by concepts like Romaiosini and the Megali Idea. Professor Leontis was the one who inspired me to become curious about Hellenism in the longue durée. The first time I ever visited Athens, she was the one who took me to the top of the Acropolis—and she even helped me to get a SIM Card and a metro map!

In your book on Lycurgan Athens you underline that the 4th century BC city invented itself as the “cultural capital of Greece” promoting its theatre industry and heritage together with its imperialist past of the 5th century BC. In what way do you think there are parallels between ancient and modern cultural politics? And “what makes people think that classical Athens is so unique?”

There’s a long history behind the question “what makes people think that classical Athens is so unique,” and much of The Classical Debt is dedicated to tracing that story. But I’ll give two versions of short answers here. First, people think Athens was so unique because the Athenians said that they were unique (Pericles’ funeral oration, as reported by Thucydides, is a critical document here). But today we think Athens is unique also for the simple reasons that we’ve thought that for a long time.

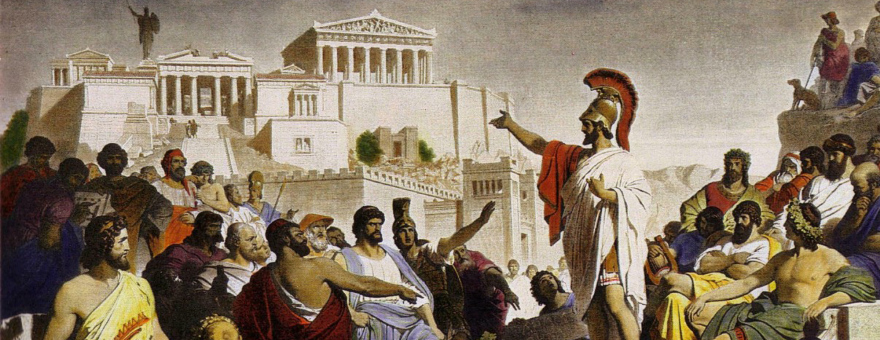

Pericles’ Funeral Oration, 1877, by Philipp Foltz

Here I find a snippet of something written by museologist Peter Walsh very useful. Walsh has argued that the reproduction is what “confers status and importance on the original. The more reproduced an artwork is—and the more mechanical and impersonal the reproductions—the more important the original becomes.” Walsh here is talking about reproductions of material artifacts, but I’m very interested in extending these kinds of critical heritage debates—debates centered largely in materiality—to the world and history of ideas. The more that, say, Athenian democracy gets invoked as a model—gets, in a sense, “reproduced,”—the more prestige accrues to the imagined concept of the “original” Athenian democracy.

“The Classical Debt” traces the ongoing “negotiation” of the Hellenic nation in the present day world arena together with Greece’s attempts to remind the west of its ‘debt’ to the ancient Hellas. How does this translate into practical policy decisions?

To answer that question in this space, I want to consider the negative side of the coin: how is the idea that Greeks today are unworthy descendants of illustrious ancestors—or not really descendants at all—translate into practical policy decisions? This is hard to measure, of course, but I think it’s a very interesting question because it stands at a real intersection between humanities (intellectual history, media studies, even classics) and social sciences (economics, political science, policy).

Mark Blyth, a wonderful colleague of mine at Brown, has repeatedly emphasized that austerity policies do not solve economic crises such as the one in Greece, but turn them into “a morality tale of saints and sinners.” The place where the humanities can shed light here is in unpacking how the Greeks are so easily cast as sinners—while the Icelanders have emerged from their own tale of financial ruin seeming all the more virtuous.

There is a long history of recorded disappointment in “modern” Greeks, and that disappointment—and disdain—has had material effects. The historian Mark Mazower writes of how, during the brutal German occupation of Greece, a “sort of vague classicism was accompanied by considerable ambivalence towards Pericles’ modern descendants.”

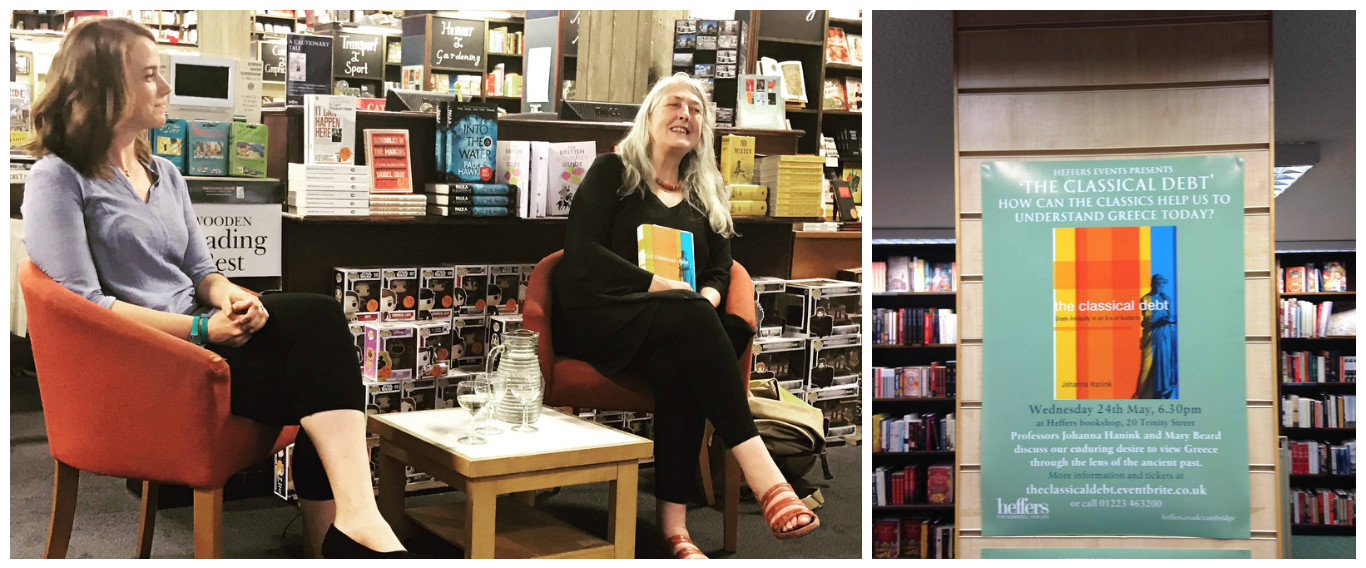

“Hanink helps us see modern Greece through the eyes of a classicist, and ancient Greece through the eyes of a keen observer of modern Greece—a wonderful and winning combination. The Classical Debt is a clever meditation on if, and why, antiquity still matters.”—Professor Mary Beard, Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge

In my answer to your first question I said classicists should stay out of it when it comes to the finer points of economic analysis of the Greek crisis. So let me say what I wish an economist or political scientist would do: I’d be very interested to see work on Greece in light of economist Robert Shiller’s recent drive toward “Narrative Economics.” Shiller debuted some of that work in January, in his Presidential Address to the American Economics Association, a few months after my own book was “put to bed” (as they say in the newspaper business). He calls for economists to pay more attention to popular narratives—to stories and storytelling—and the influence they have in driving economic events and trends. One example, an example that suggests this kind of analysis might be fruitful in the case of Greece, is the narrative that came to see the stock market crash of 1929 as retribution for the decade’s loose morals. Sermons preached the Sunday after the crash cast it as “a narrative of a sort of day-of-judgment on the “Roaring Twenties.”

In the case of Greece, I’d like to see work on “narrative economics” from two interrelated angles: 1) how has the narrative of Greek cultural/civilizational decline affected policy, and 2) how has that narrative affected how the world has perceived Greece and its economy, and what further narratives (about, e.g., the Greeks’ work ethic, spending habits and so on) about the economy have taken root.

The connection between ideas about Greek antiquity and modern economic policy might seem a bit tenuous. But I have heard that the cultural importance of ancient Greece has been raised by economics ministers at Eurogroup meetings!

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis

Read also: On Not Knowing (Modern) Greek

art by Mali Skotheim

N.N.