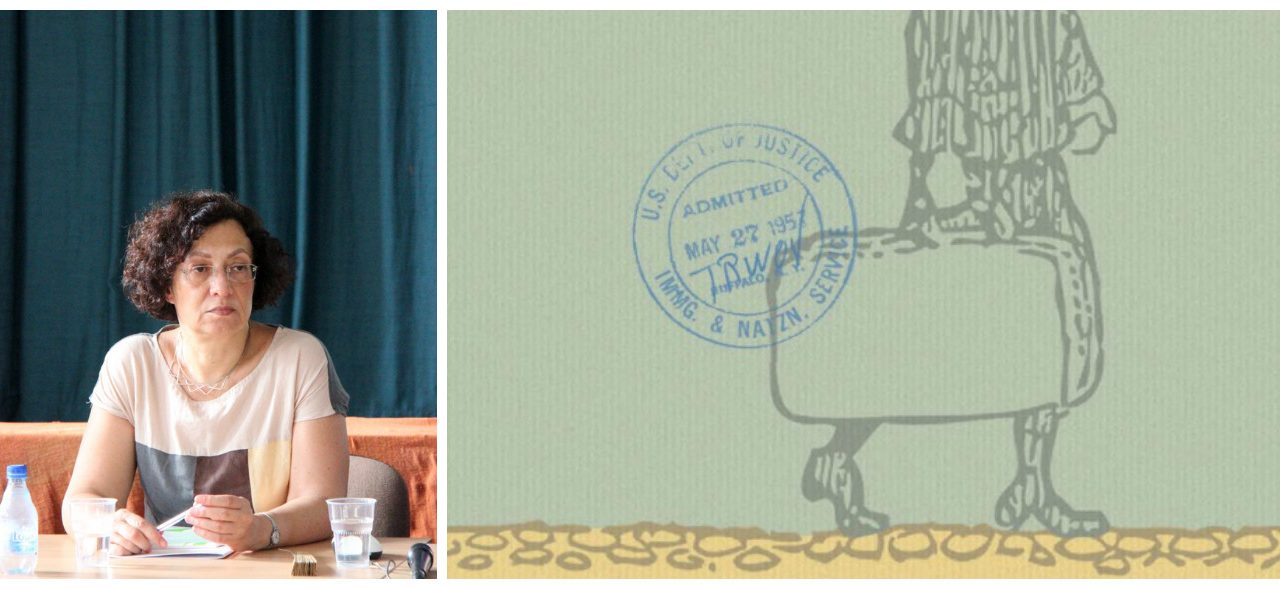

Lina Venturas is director of the Research Unit for the History of Migratory and Refugee Movements at the Panteion University and she has been scientific coordinator of the “Migration Management and International Organizations: A history of the establishment of the International Organization for Migration” (MIMIO) research Programme. She is also head of the Ministry of Education Research & Religious Affairs Scientific Committee for the integration of refugee children in education.

Professor Venturas spoke with Rethinking Greece* about the waves of Greek emigration to the US, Northwest Europe and Australia as part of wider population movements from agricultural economies to industrial countries, the key role human mobility has played in the development of the modern and contemporary world, the programme for integration of refugee children in the Greek educational system and the importance of according legal status and other socio-economic rights to refugees and migrants.

Overall, both the turn of the 20th century movement to the USA and post-war emigration, form part of broader population movements from agricultural economies to countries with a strong and expanding secondary sector. These movements were largely dictated by the receiving states’ labour market needs; they mainly involved peasants from agricultural countries who settled in urban areas of the host countries and were transformed into proletarians. In the post-war era these overseas movements continued; some 140,000 Greek migrants settled in the USA, 175,000 in Australia and 86,000 in Canada. But, after the enactment of the German-Greek migration agreement in 1960, Germany became the main destination of emigrants. 61% of post-war emigrants went to Northwestern European countries, while emigration to West Germany alone accounted for 53% of the total number of emigrants in the period 1960-1977. There was a significant change in the geographical provenance of post-war migrants to Europe as they now departed mostly from the North of Greece: Macedonia contributed 36% of all migrants and 44% of those who went to European countries during the post-war era.

Post-war immigration to Western European countries was subject, much more than migration to other continents, or during other periods, to a policy of organised labour importation, drafted by the host countries’ governments and employers and regulated bya temporary contract labor system, bilateral migration agreements and the implementation of welfare policies. Many young Greeks were persuaded to leave the country through the combination of active recruitment by Western European countries and especially Western Germany, the wages these countries offered (which were three times higher than in Greece) and the relative security of an employment contract and the various social benefits.

Whereas overseas emigration was seen by receiving countries as largely permanent, outflows directed to Germany and other European destinations were intended to be a temporary import of cheap labour. Therefore, although immigrants that settled in European countries were accorded social rights, they were not naturalized, due to the receiving states’ policies. Greek immigrants in European states secured jobs and steady incomes and enjoyed a significant improvement in their standard of living. Nevertheless, deindustrialization and the economic transformations instigated by the oil crisis of 1973, did not allow for significant social mobility. Furthermore, both the receiving states and Greece adopted policies concerning the education of migrants’ children which did not facilitate their upward mobility.

Safeguarding the right of refugee children to education has been a major concern of the Greek Ministry of Education, teachers, academics and many others. The objective of the Greek state is to ensure psychosocial support and to integrate refugee children in the Greek educational system, without burdening schools with an excessively large number of children who do not speak Greek and have not been appropriately prepared to attend a Greek school. In March 2016, the Ministry of Education Research & Religious Affairs set up a Scientific Committee to form a plan for the integration of refugee children in education; this plan had to be designed in such a way so as to increase the chances that refugee children succeed at school and do not abandon it.

For the school year 2016-2017, the Scientific Committee considered the specific need refugee children had due to the fact that they were experiencing a transition from war to normality. Furthermore, owing to wars and being continuously on the move, a significant percentage of refugee children had been outside the school environment for years, and many children had never attended school, although they were of school age. Additionally, many children are burdened by psychological traumas. In order to meet their needs, emphasis needed to be placed on their adaptation and familiarization with the school environment and on cultivating a sense of security, communication and acceptance. A transitional education program was also considered necessary as these children do not speak Greek and many had to cover gaps in their education due to their long absence from schools.

The refugee population living in Greece is quite heterogeneous in terms of characteristics and fluctuating in numbers. So, predicting the exact number of children that will stay in Greece is not easy; neither is the duration of their stay or their place of residence. Therefore, the Ministry of Education Research & Religious Affairs had to take into account the insecurity and instability of the situation and prepared for multiple scenarios in terms of the numbers and locations. An additional issue making planning difficult was the fact that the children who will probably stay in Greece belong to different legal status categories: There are children whose parents have been accorded refugee status; others that are waiting for relocation or family unification without being sure about their departure or the departure date; also children whose families have submitted an application for asylum that is yet to be considered, others who live on the islands, unaccompanied minors etc.

With the exception of the children whose parents have been given refugee status, it is impossible to predict if and when the status of the others will be regulated, or when and how many of them will be relocated. However, given the fact that we are talking about children, the needs of the entire potentially existing population had to be provided for and covered. Furthermore, as shown by a number of studies, the trend in the migration and asylum policies of the EU is the long wait of immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers under a quasi-precarious regime.

How does this uncertainty impact the refugees’ attitudes towards formal education?

Refugees that crossed to Greece did not aim at settling here; fully aware that it is almost impossible to find work, they aimed at moving to other European countries. Remaining stranded for a long time in Greece caused insecurity, either because they were waiting for an answer to their for asylum/relocation request or because those refugees who could not look forward to these solutions were looking for other ways to leave the country. After the closing of the borders and the European Union-Turkey agreement, the legal status and the relocation prospects to another country of the various refugee groups -in mainland Greece and on the islands- started to change. Under these conditions, the refugees’ attitude towards formal education was, and still is, ambivalent. The feeling of precariousness is, still today, intensified by the fact that a significant percentage of refugees still live in Accommodation Centers and, what is more, they are frequently moved from one to another. With a view to remedy this situation, many refugees have been moved for some months now by the High Commissioner or other agencies to flats, hotels and shelters in Athens, Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Livadia, Kilkis, Arta, etc. The Ministry of Migration Policy aims at expanding the accommodation program in such urban facilities and decreasing the number of refugees living at Accommodation Centers.

Now that the school year is over, what is your overall assessment of the program for the education of refugee children in Greece?

The effort to integrate refugee children in the educational system for the 2016-2017 school year, was not without difficulties, mistakes and omissions, there were however, equally significant achievements. The basic omissions concern the non-implementation of the Scientific Committee’s proposals for the operation of kindergartens and non-mandatory education programs for children over 15 years old. The organization and operation of obligatory schooling also faced many problems, weaknesses and delays as all refugee children had to be vaccinated. Furthermore, there was a relatively high percentage of dropouts, while irregular attendance was also registered (although the percentages were number similar to those of other countries), mainly due to the unstable and adverse conditions under which refugees live, which are intensified by institutional and educational omissions and deficiencies.

Finally, there was inadequate and delayed information and sensitization of several local societies and, as a result, there were few, but vociferous local reactions which were reproduced by the media. Nevertheless, in laying down the foundation for school attendance and social connection, the Ministry of Education Research & Religious Affairs took the first step in the integration of refugees. The social and political bet of getting refugees out of the ghetto of camps, bringing back some normality to refugee children’s life, familiarizing them with the school system, and finally, making refugees more visible in Greek society, has been won to a great extent. All this has occurred against a difficult background, if we look at the wider European and international reality right now. These achievements are important, given that refugees have limited opportunities for interaction with Greek citizens and social integration in general. These accomplishments are also of great significance because they constitute a starting point for the greater acceptance of refugee rights and their integration in Greek and European societies.

Thessaloniki Museum of Photography: Another life: Human flows / Unknown Odysseys

Thessaloniki Museum of Photography: Another life: Human flows / Unknown Odysseys

Integration is an open-ending, multi-factorial social process that extends over time. Global and local asymmetries, international and social hierarchies, combined with transformations in the economic sphere and labor markets, play a major role in processes of social and cultural integration. Most of all, integration depends on whether refugees and migrants are accorded a legal status and rights and are able to gain a decent living in their host country. So, residence and work permits, social and other rights, along with economic relations and the structure of the labor market in host countries, are of great importance. It is of great importance that refugees and migrants feel that they are recognized and respected as human beings, like the citizens of the host country: when they are stigmatized and scapegoated, collectively condemned for the acts of an extremist or a criminal with the same national/cultural background, then they rightly feel that whatever their personal views and actions are, they will be excluded from society.

Instead, when people reasonably aspire to live with dignity, safety and make a decent living, when they have opportunities to improve their families’ future, then they are motivated to learn the language of their host country, to adapt to new conditions and to participate in society. Both the UK and France are relatively affluent consumerist countries with a colonial background that, since the 1980s, have adopted economic, social and political measures that lead to the exclusion of a significant part of their citizenry from the labor market and social benefits. Furthermore, the EU, during the last decades has adopted neo-colonial policies vis-à-vis developing countries and a hostile stance towards the refugees and migrants coming from them. In both the UK and France islamophobic discourses have been legitimized by several politicians and media. These factors and their economic, social, political and cultural consequences weigh, in my opinion, more heavily than multicultural or assimilationist policies on social relations and integration processes.

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi