Thomas Maloutas is Professor at the Department of Geography, Harokopio University. Former Director of the Institute of Urban and Rural Sociology of the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE) and General Secretary for Research & Technology (2015-2016). His work is related to the changing social structures in metropolitan areas in the era of capitalist globalisation with a focus on issues of segregation and gentrification related to housing and broader welfare regimes. His research and published work refer mainly to the South European urban context and especially to Athens.

Professor Maloutas is the chief editor of the Athens Social Atlas project that aims at highlighting and critically analysing topics concerning the social geography of Athens through multiple perspectives, focusing especially on the past 20 years. It contains texts and supporting material concerning the historical development of the metropolitan area from the 19th century on, the city’s social stratification, its governance, its international economic role, migrant groups, housing practices, the daily transport of its residents.

Thomas Maloutas spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the background and methodology for the “Athens Social Atlas” project, Athens’ isolationist and cosmopolitan characteristics, its social and professional stratification, its suburbanization, the decline of its centre, the high rates of home ownership and how construction in the 50s and 60s destroyed the face of the city. Maloutas underlines that nowadays “Athens has more problems than one can see with the naked eye” and that there is need for a consistent housing policy, as well as new social solidarity policies to accomodate the increasing numbers of refugees living in Greece and those in danger of losing their homes.

What is the level of scientific and public awareness concerning matters of social geography of Greece and most specifically of the city of Athens?

There is an increasing awareness of matters related to life in the city as well as to social geography. The spatial dimension of social issues is more obvious in an urban context, where one could observe contrasting situations juxtaposed in close proximity, as for example, poor neighborhoods right next to wealthy ones, diverse nationalities and people living side-by-side, etc.

As people move around and travel much more than in the past, they are able to directly compare diverse social circumstances, which in turn increase their awareness of deepening inequalities in the last 15-20 years or so. Social issues are thus more visible to the wider public.

What is the purpose of the “Athens Social Atlas” project?

The Athens Social Atlas is a research based project, although not a scientific one per se. All contents originate from serious research projects, small and large, individual and collective. The Atlas is a compendium of work in concise form, where methodological analysis is not excessively detailed and chapters outline the broad shape of the matter, the supporting empirical data, as well as the corresponding political dimensions. It’s a collective effort in which 75 authors have already contributed, with numbers increasing as the project is ongoing.

At the outset we thought we would be making a typical Atlas in printed form. For example, back in 2000, I’d edited what was thought to be the first volume of an Atlas called The Social and Economic Atlas of Greece, which focused on cities, whilst subsequent volumes were to be on rural areas, industrial activities and tourism respectively. Sadly this project was never completed, but a more comprehensive French edition of that Atlas was published in 2003 (with Michel Sivignon, Franck Auriac, Olivier Deslondes and myself as editors) called “Atlas de la Grèce” that included cities, rural areas, industrial activities and tourism.

These days however we can have an online Atlas that can be updated on a regular basis. Hence, this new Atlas is a work in progress, and as such, it functions as a kind of a forum as well. The only limits imposed by the project’s editorial board relate to contributions of material and arguments being founded on research. The Atlas is supported by the Onassis Foundation.

Can you tell us a few words about Athens as a city and an urban phenomenon? What are its special characteristics?

In a very broad sense, each city is unique; however, modern cities studied by disciplines such as urban social geography, urban geography or urban sociology are industrial cities. Moreover, cities like Athens have the disadvantage of not being situated where urban theory is produced. Accordingly, when looking at a city like Athens through theoretical lens developed elsewhere for differenttypes of cities, it is quite likely that what is being seen is not really understood.

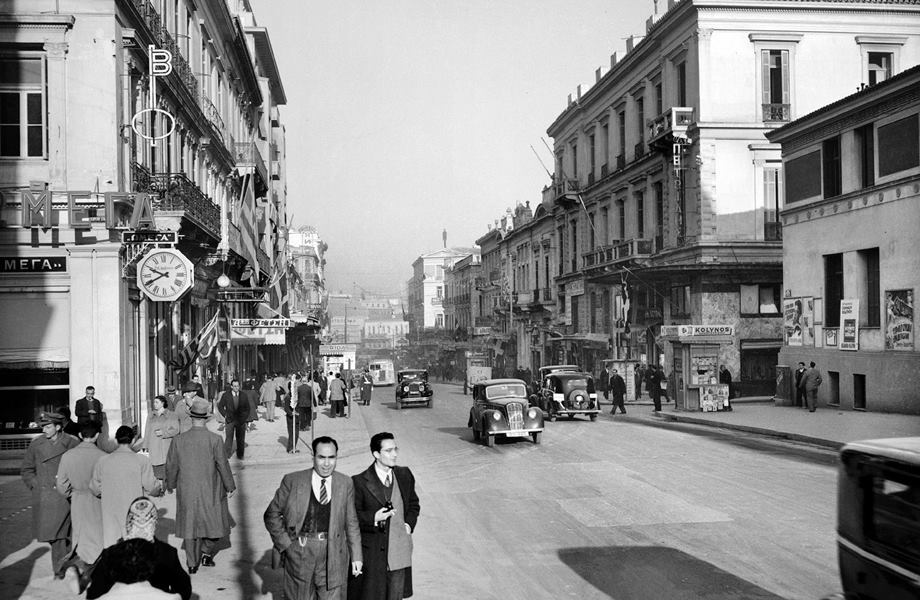

In the course of the 20th century, Athens became a large metropolis of almost 4 million people, evolving from a small town of roughly 100,000 at the turn of the century by way of an atypical process, i.e., insofar as this didn’t take place through the characteristic process of industrialization. Here, other historical factors had been at play, from the designation of Athens in 1834 as the capital of the newly independent Greek state and the subsequent attempts at city planning by the Bavarian monarchs that indelibly affected both the way the city developed over time and how different social groups established themselves in certain parts of the city.

Other major events played part, as for instance the aftermath of the Asian Minor expedition in the early 20th century that led to the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, whereby close to 1.5 million of people of Greek origin from Asia Minor moved to mainland Greece with a vast proportion concentrating in Athens. The sheer scale of this intake as well as the way these refugees were distributed in various neighborhoods surrounding Athens irrevocably affected the social fabric of the city.

This upheaval was followed by World War II, followed by a Civil War and a huge rural exodus mainly towards the big cities and Athens. Thus, in the postwar decades there was an enormous inflow of people from the countryside to Athens and to a much smaller extent to Thessaloniki; at the same time, there was a massive, almost equal in scale, wave of emigration from Greece to West Germany. Moreover, some migrated, either internally or externally, due to political reasons: for those defeated in the Civil War, it was not easy to live in small villages, where they were extremely visible. Another factor driving people out of rural areas were the dire economic conditions that led families to develop their own strategies in orderto help their members get back on their feet: for instance, a part or branch of the family would move to the city, while another would move abroad. These were not necessarily desperate solutions, but choices of accommodation and rational use of resources.

Athens thus became a place that received people fleeing from elsewhere. Whilst in most of Western Europe or North America we observe urban centres attracting people on the basis of their industry and economic development, this was not the case in Greece.

According to French Geographer Guy Burgel, Athens has been “a city of peasants and an introvert national capital” although with some cosmopolitan features. Does this account still hold?

According to French Geographer Guy Burgel, Athens has been “a city of peasants and an introvert national capital” although with some cosmopolitan features. Does this account still hold?

Many things have changes since the mid-70s when Guy Burgel made that statement; I certainly do not believe that this account stands today. Since the 80’s we have stopped witnessing that constant stream from rural to urban areas; there as a geographic stabilization of population within the national territory, and the policies of the governing PASOK socialist party in that decade played a part. Moreover,a society cannot be on the move forever, and eventually urbanization trends become more or less stabilized. In Athens, for the past 20 years the population in terms of Greek nationals has stabilized, if not declined. Overall, there is a small increase in the total population of the city, mainly due to migrant inflows. To a certain extent, it is also the case for other Greek cities. Consequently, we can no longer speak of Athens as a city of peasants. The generation of peasants that came to the city is now at the end of their biological cycle. The new generations are autochthones, Athenians.

As far as the city’s cosmopolitan features are concerned, there is this debate whether Athens is an introvert city, as the capital of a country isolated by its shared borders with countries either till recently in isolation because of the cold war or with which there have traditionally been difficult relations. With the exception of Italy, Athens does not have a hinterland outside the national territory and cannot easily connect with other big metropolises. On the other hand, there is a certain cosmopolitanism because Greek people tend to move for work and studies around the world, experience, bring back and transplant other cultures. So we have a city which is not very well connected globally, but its people have visions and images of the outside world. In Athens you thus have a kind of cosmopolitanism and an isolation at the same time.

With the dramatic increase in the brain drainsince the beginning of the crisis, now there are ten times more young people with high skills leaving Athens to seek work elsewhere; this is an intricate problem. I believe that in the 2021 census the scars of this phenomenon will be visible in the structure of employment, in the economically active population of this country.

What are the main characteristics of social and professional stratification in Athens? How is Athens evolving in this respect?

The general view according to some scholars -as for example Saskia Sassen, who has visited Athens- on the future shape of urban societies is that they tend to become polarized: the wealthy, as well as the poor become more numerous, while the middle class is shrinking and income distribution is taking the form of an hourglass instead of an onion, as it was before. This is interpreted as the result of moving from industrial economies to post-industrial service-based ones. However, this theoretical model has been seriously questioned as to whether it actually applies to all cities or only to very special places like New York or London.

Empirical studies for Athens do not reveal a substantial widening of the gap between the rich and the poor, ad this is so for many reasons: One, because Athens has never been a locus for big corporations to establish their business here or to at least develop important activities. This means that Athens does not attract a corporate elite, young people with very high academic credentials and very good salaries, who form this kind of upper caste in most of the cities discussed in Sassen’s model. In Athens, the corporate elite is anemic. As far as the number of poorer people is concerned, it was shrinking until the late 80s due to upward social mobility. However, with the massive arrival of immigrant groups, poorer classes are becoming more numerous. In a nutshell, even though we don’t have a widening gap between rich and poor, the number of poor people is indeed increasing.

As far as gentrification is concerned, this is mainly a process evident in the English-speaking world, especially in the New World, where the elite, during the advance of the industrial revolution, decided to leave the city centre and live in the suburbs. When industrial development came to an end, it created increasing vacancies in the inner city areas, so you have reinvestment and the return of a portion of the middle classes. However, this happened mostly in the English-speaking world: in cities like Paris or Vienna, the elite had not left the inner city in the course of industrial development, so there was no space for cataclysmic changes through gentrification.

Gentrification in Athens is not related so much to housing, as to the changes of use of public space in some areas like Metaxourgeio, Gazi or Psirri, where local artisans and small scale industry were replaced by leisure activities, such as restaurants and bars. This also changes the city, but it’s not the usual type of gentrification.

It seems that the centre of Athens has experienced a decline after the 1980s…

The decline of the centre of Athens began in the mid-70s, in a gradual process that is still going on. According to data from the last census (2011), the municipality of Athens has lost almost 150,000 inhabitants as compared to 2001. Without the influx of migrants in the city centre, the loss would have been much greater.

Usually, suburbanization is due to industrial development. In the case of Athens, middle and upper middle classes have begun moving to the suburbs because they themselves had overinvested in inner city construction, making it too densely built and insufferable. Construction, since the 50s and during the dictatorship (1976-1974), had been encouraged as a means to heat up the economy and ensure political gains. In 1968 for instance, the military regime, in order to gain the favour of land owners, relaxed prevailing limits on construction space as percentage of land by a further 20%. This was implemented without serious town and street planning. Thus in Athens overall there was short-sighted approach to construction seriously lacking planning, especially during the dictatorship years.

Does this over-construction of Athens begin before the 1967 dictatorship, that is, in the Konstantinos Karamanlis era of the late 50s?

Τhis is an issue of contention: On the one hand, there were very high construction rates in the 50s and 60s that destroyed the face of the city, when neoclassical and other architecturally significant buildings were knocked down and replaced by much bigger modern apartment buildings, while on the other you have the production of very affordable housing. So, there was a socially positive outcome in terms of housing and a socially negative outcome in terms of the layout of the city and living conditions. After over-building neighborhoods like Patissia, Kato Patissia, Kypseli, and a few other middle class and sometimes upper middle class neighborhoods, they became degraded and the more affluent households who were partly responsible for that decline gradually began moving to the suburbs.

In Greece, the housing sector was the driving force of the entire economy. In industrial societies, it is commonly industry that produces goods and creates wealth that triggers construction; in the case of Greece,it was a little bit the other way around. An immense development in construction demanded the production of goods for housing, from furniture to building materials and set the economy in motion.

Crisis-struck Athens is commonly depicted in international media with abandoned buildings, vacant shops and homes. What social problems lie behind these images?

Let’s say that Athens has more problems than one can see with the naked eye. On the Atlas website there is a chapter on vacant dwellings with maps showing not only holiday homes -mainly situated on the coastline of Attica- but for the first time we witness a large number of vacant homes in central Athens. Vacant buildings however could be a resource for the city, creating available space for housing homeless or other vulnerable groups of people.

In Greece, the vast majority of landlords are not companies, banks or corporations but mostly older people who invested in property. The majority of homes also owner-occupied: home ownership is about 70% in Athens and over 80% in Greece as a whole. Overall, landlords do not own more than one or two apartments other than own residence. Such property owners have also been hit by the crisis, losing their income from property either because of loss of tenancies or undelivered back rental payments or serious decreases in rental charges as tenants are unable to meet rental costs.

The existence of many vacant dwellings on the one hand and homeless people on the other begs for a policy that combines needs with remedies. Can homeless people be housed in those empty homes? These properties are privately owned, but owners are themselves in danger of losing their property after years of not being able to pay their property taxes and accumulating debt.

To face this problem, new policies need to be implemented in order to coordinate assistance for people with housing needs, while facilitating small property owners to keep their property. One idea would be to rent these homes at a price much lower than market value and ask tenants to provide another kind of social service for others in need. This way, social relations could be rebuilt on the basis of solidarity rather than just generosity, which I believe is the only way to shield poorer neighbourhoods from the infiltration of xenophobic or racist groups, including neo nazi party elements (Golden Dawn).

I believe we should salvage social relations by implementing social policies that bring people from different backgrounds closer together. Helping each other is something that Greeks do, but it is usually kept inside the family. However, new social solidarity policies are needed at this juncture, given also the large numbers of refugees living in Greece. In this framework, Athens’ empty apartments could also be used as a means of solving social problems, without stigmatizing people or turning whole neighbourhoods into ghettoes.

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis