Maria Petmesidou (Ph.D. Oxford University) is Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at Democritus University of Thrace, and Fellow of CROP (Comparative Research on Poverty) of the International Social Science Council under the auspices of UNESCO. She has published extensively on social policy and welfare reform in Greece and Southern Europe. Recently she co-edited the books: Economic crisis and austerity in Southern Europe: threat or opportunity for a sustainable welfare state? (London, 2015) and Child poverty and youth (un)employment and social inclusion (Stuttgart, 2016). She has also co-ordinated the research programmes “Health and long-term care in Greece” (2013-2015, funded by the Institute of Labour) and “Policy Transfer in the field of Youth Employment Policies” (2014-2017, funded by the Europan Commission under the STYLE project).

According to Petmesidou, despite rising social spending after the 80’s, poverty rates remained high and stable over the last decades: overall, Greece under-spent in social protection in terms of its wealth. The crisis facilitated reforms towards system rationalization but did so under conditions of severe spending cuts and receding public provision, gravely harming the middle and lower-class. In a scenario of increasing social polarization and sharp contraction of the middle class the move towards a mass-supported comprehensive, rights-based welfare state is not on the horizon. Neither are there any signs of reinvigoration of “Social Europe” that could have a positive effect on the welfare state future in the country. It is quite likely that disillusioned and impoverished strata may switch political support to right-wing parties. In conclusion, instead of the trodden path of a tourism-based economy, supplemented by low value-added manufacturing, an alternative scenario would be a move towards a robust industrial structure and innovation system, which would tap into niche-markets for high-value added products, and could support a more socially embedded form of flexibilization, combining flexibility with security:

How do you believe the welfare system in Greece compares to other systems in Europe? Is it a part of a South European model? What are the economic and social factors that can help us understand welfare politics in Greece?

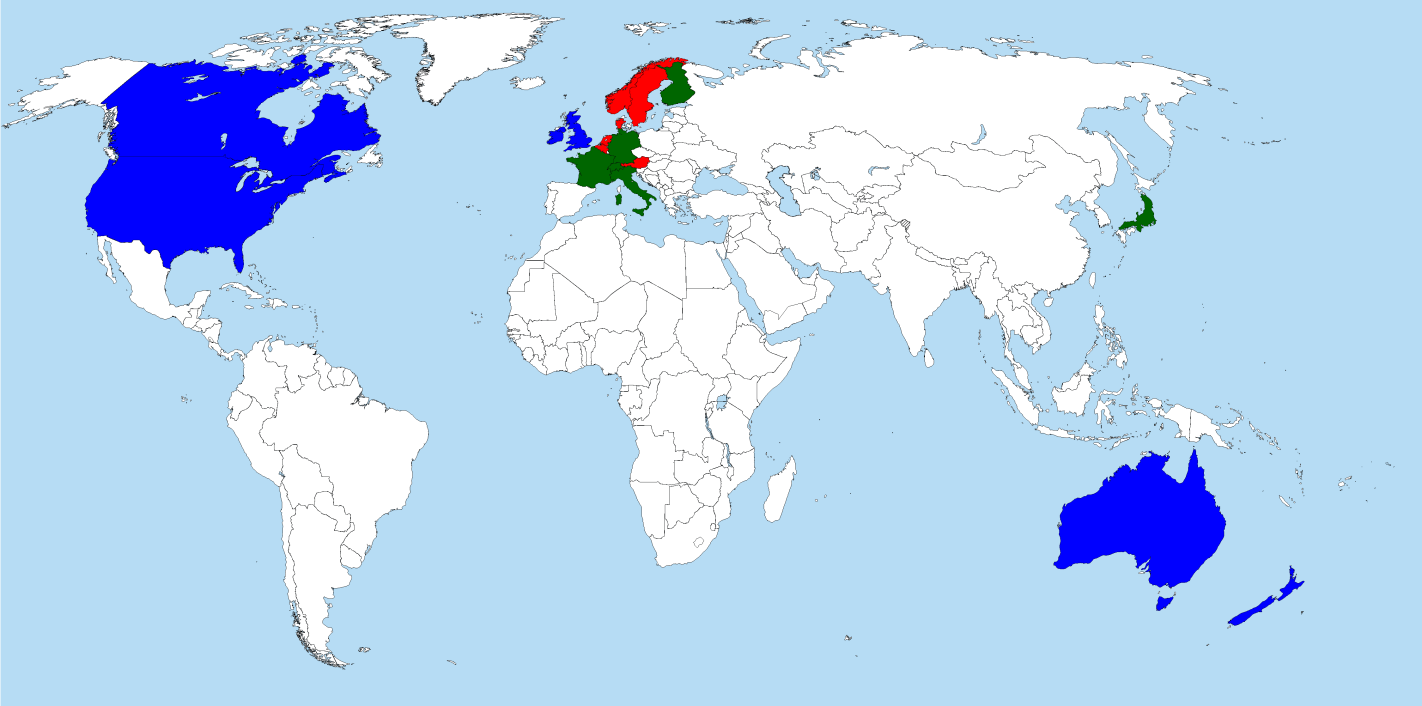

Greece shares a number of characteristics with the other three South European countries (Italy, Spain and Portugal) regarding social and welfare structures. Late industrialization, a record of authoritarian regimes until late in the post-war period and political clientelism (of less prevalence in the Iberian Peninsula though) are among the main features that account for the “lagged” welfare state development in these countries, compared to North-West Europe. In relation to the three welfare state regimes typology –as identified in the well-known work of Esping-Andersen (“The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism”, Polity Press, 1990), welfare arrangements in South Europe have been for a long time characterized by a “hybrid” form that combines elements of all three welfare regimes.

First, income transfers (primarily pensions) developed on an occupational basis, according to the Bismarckian model of continental Europe. But social insurance systems remained highly polarized and fragmented, compared for instance to Germany, France and other countries. Fragmentation has been most prevalent in Greece and this is reflected in the very large number of social insurance funds (about 130 until recently) that are characterized by great inequalities in the scope, generosity and quality of their provisions. Second, between the late 1970s and early 1980s, in all four South European countries, a social-democratic element (a feature of the “social-democratic” welfare regime of Scandinavian countries) was introduced in healthcare with the establishment of a national health system providing health services free at the point of use. Yet in Greece this shift to a national health system remained incomplete until recently. Private health expenditure kept growing and the system has been halfway stuck between a highly fragmented social health insurance and a national health service model.

First, income transfers (primarily pensions) developed on an occupational basis, according to the Bismarckian model of continental Europe. But social insurance systems remained highly polarized and fragmented, compared for instance to Germany, France and other countries. Fragmentation has been most prevalent in Greece and this is reflected in the very large number of social insurance funds (about 130 until recently) that are characterized by great inequalities in the scope, generosity and quality of their provisions. Second, between the late 1970s and early 1980s, in all four South European countries, a social-democratic element (a feature of the “social-democratic” welfare regime of Scandinavian countries) was introduced in healthcare with the establishment of a national health system providing health services free at the point of use. Yet in Greece this shift to a national health system remained incomplete until recently. Private health expenditure kept growing and the system has been halfway stuck between a highly fragmented social health insurance and a national health service model.

Third, social care services and social assistance are under-developed. Scanty provision of social assistance to the neediest through means-testing indicates a liberal orientation (manifest in the liberal welfare regime of the Anglo-Saxon countries). In the other three South European countries, limited statutory coverage in social assistance triggered a more or less dense network of NGOs, with the Catholic Church (through its well-known organization “Caritas”) playing a significant role in this respect. In Greece however third sector social activity remained restricted. This can be partly attributed to the values of Eastern Orthodoxy and its historical limitations of social activism, which hardly provided fertile ground for institutionalized volunteerism. The recent crisis has significantly increased volunteering, as a fast growing number of people struggling for the basics (food, rent and utilities) are turning to charities. Nevertheless, even amidst the crisis, the percentage voluntary work for an organization in Greece is far below, for instance, that in Italy (8% of citizens in Greece, compared to 20% in Italy, and about 25% in the EU27, according to Eurobarometer 2012).

Another major feature of South European welfare states is that they started expanding at the time when economic strains –linked to deepening globalization and the ascendancy of neo-liberal ideas from the late 1970s onwards– had shaken the politico-ideological legitimacy of welfare states, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world. At the same time, demographic ageing, new social risks of precarious employment, long term unemployment, in-work poverty, changing family patterns and gender roles exerted pressures for restructuring and cost containment. Soon fiscal constraints became highly pressing in Greece (and in the other South European countries) particularly under the project of joining the European Monetary Union. In these countries, reform had to confront not only the above mentioned new problems, shared to one degree or another by all European societies.

Especially in Greece, reform equally needed to address the issue of rationalization of the social protection system by tackling extensive fragmentation and deep inequalities, while at the same time expand coverage to a number of deprived social groups for which hardly any social safety net existed (those employed in the underground economy, the young unqualified persons without work experience, the long-term unemployed and particularly unemployed women, old-age people with no rights to social insurance and other vulnerable groups). In the decades prior to the crisis, responses to these pressures by South European countries differed significantly, ranging from minimal change in Greece to more profound reforms in Spain, Italy and Portugal.

Also, I would like to stress that, in order to understand welfare politics in Greece, we have to look at the historical origins of public welfare in the late 19th-early 20th century, when the first social insurance funds were established. These laid the ground for a stratified system where different occupational groups are covered by distinct programmes – consisting mostly of cash benefits – with great differences both in funding and provisions. Well-entrenched legacies of fragmentation, deep polarization and particularism were further established in the 20th century as social insurance expanded. These features are closely linked with the wide legitimation of rent-seeking behaviour patterns, ingrained in statist-clientelist structures and practices, which dominated socio-political integration in the country for a long time. “Political credentials” have persistently functioned as crucial means for the appropriation of resources. They defined access to clientelistic networks (and the “revenue-yielding” mechanisms of the state) by households, individuals and businesses.

These conditions hardly favoured universalistic social citizenship values. Instead they cultivated a perception of social problems in individualist/familialist terms, with the family playing a crucial role in pooling resources from various sources (the formal and informal labour market, welfare benefits, access to public employment and others) in order to provide support to its members. I call this pattern a “male breadwinner/familialist” regime. The term “male breadwinner” reflects women’s “ancillary status” in labour market and social insurance, as most often women are entitled to derived rather than individual social insurance rights. The term “familialism” captures the key role of the family in welfare provision.

Greek political science and Greek public discourse have been strongly influenced by the “underdog vs. modernist culture” paradigm and a general view of Greece as an exception from the European canon. Would you like to comment on this?

In my view, what makes Greece different from the European canon is the historical consolidation of statist-paternalistic structures in the 19th and in much of the 20th century. Socio-political conflicts focused around access to the state and its revenue-yielding mechanisms. I cannot expand on the historical origins of this form of socio-political organization. Suffice it to say that a mode of income generation and distribution, in which the state functioned as a vast apparatus for creating and distributing wealth, income and benefits by extra-economic, i.e. political, means and criteria, has been a prominent characteristic for a long time. This significantly influenced the country’s particular social and economic development. This feature does not limit the pre-eminence of market processes in the economy, but stresses that in some domains these processes were extensively conditioned by political intervention (creating “windfall profits” and “political rents” for those groups that enjoyed access to the poles of political power). In the political history of Greece we find several examples of divisive identity politics that provides political credentials of access to the state to certain groups, excluding others. For instance, during much of the postwar period, the prevailing division was between “Nationalists” (ενθικόφρονες) and “Communists” (κομμουνιστές, μιάσματα). After the restoration of democracy, a new division emerged between the “Progressives” (under the banner of PASOK) and the “Conservatives”, which extensively reshuffled the groups enjoying access to the revenue yielding mechanisms of the state.

Strong forms of statism and paternalistic social organization in combination with familialism and clientelism originate in Eastern autocracy. Political parties dominate civil society and this limits the ability of the latter to create a value system independently of statist practice and ideology. These conditions considerably hindered the development of rational-bureaucratic structures, collective solidarity and universalist social citizenship values. Instead, the dominant culture supported a particularistic/discretionary system of welfare provision. Hence the high degree of fragmentation of social insurance, the great inequalities and gaps in coverage and in the range and level of benefits, as well as the strikingly low redistributive effect of social spending.

Extended social protection in Greece essentially begun in the 80s. What were the characteristics of the welfare system that was established then? What were the obstacles in building a fair redistribution system?

PASOK’s landslide victory in 1981 created a propitious environment for expanding social welfare. Social spending increased rapidly during the 1980s: from 12% of GDP in 1980 to 22% in 1990.Social security coverage was extended and improved (both in rural and urban areas) and the “social role” of the state was strengthened. However, the fast expansion of social expenditure was not accompanied by any changes in the composition of social benefits. Heavy reliance on pensions persisted while social service provision hardly expanded. Also the logic behind the distribution of social benefits did not change. Clientelistic exchanges continued to play a dominant role, further strengthening the unequal distribution of privileges among social groups. Rather than building comprehensive, rights-based welfare arrangements, policy measures provided favourable concessions in a discretionary manner, such as early retirement schemes and various cash benefits for certain socio-occupational groups. These concessions exerted considerable strain on the social insurance funds’ finances. Already by the mid-1980s, the total deficits of social insurance funds reached 16.7% of their revenue and 3% of GDP. Under these conditions, the consolidation of a number of socio-political “veto” points greatly hindered reform towards system rationalization and a fairer redistribution. Markedly, despite rising social spending, the poverty rate remained high and stable over the last decades. This indicates that actual redistribution has been persistently limited.

The attempt to introduce a national health system in the 1980s provides a stark example of the obstacles confronting reform. Law 1397 of 1983, which established the national health system (ESY), purported a radical change towards universal entitlement, linked to citizenship and a fairer distribution of health resources. Major stipulations in the law included uniform funding and service provision for all citizens, the gradual absorption of the private by the public sector and a more balanced regional distribution of health infrastructure and personnel. Yet these provisions largely remained on paper and the implementation of the law did not significantly change the status quo in health insurance. Universal access was limited to hospital care, primary care was neglected (largely provided by the private sector), private spending continued to rise, and many privileged health insurance funds maintained their prerogatives.

The watered down version of reform that PASOK finally implemented was a politically expedient solution as the government was confronted by strong veto points within the medical profession and the privileged health insurance funds. Thus, quite soon after the proclamation of a radical reform, social policy returned to its old patterns. It took a major economic and financial crisis and strong outside pressure by the country’s international lenders (the so-called “Troika” – the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank) for some major provisions of the “path shift” introduced in 1983 to be progressively materialized (namely, the unification of health funds, the standardization of contributions and of the benefits package across socio-occupational groups etc.). Albeit, under conditions of harsh cuts in funding and receding public provision.

The watered down version of reform that PASOK finally implemented was a politically expedient solution as the government was confronted by strong veto points within the medical profession and the privileged health insurance funds. Thus, quite soon after the proclamation of a radical reform, social policy returned to its old patterns. It took a major economic and financial crisis and strong outside pressure by the country’s international lenders (the so-called “Troika” – the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank) for some major provisions of the “path shift” introduced in 1983 to be progressively materialized (namely, the unification of health funds, the standardization of contributions and of the benefits package across socio-occupational groups etc.). Albeit, under conditions of harsh cuts in funding and receding public provision.

According to some analysts, rising social spending during the last three decades has contributed to the crisis, in the sense that the Greek welfare state grew to a level the country could not afford. Do you agree with this assessment?

Ι do not fully agree with this statement. The problem is perverse redistribution, reflected in the persistently high poverty rates. For a long time, acquiring resources through rent-seeking statist-clientelistic practices functioned as a substitute of a welfare state, and this has perverse distributional effects. It is true that profligate borrowing by successive governments in order to fund “clientelistic” pay-outs, has contributed to the sovereign debt crisis. But this does mean that there was an overgrown welfare state. On the contrary, Greece lagged behind other EU countries in developing welfare state institutions, particularly social services.

Social spending rapidly increased over the last three decades prior to the crisis, and EU funding flowing into the country significantly contributed to this. However, we must keep in mind the following: First, Greece started from a comparatively low spending level in the early 1980s (12% of GDP) and at the onset of the crisis it still lagged behind the EU-15 average (24% of GDP in Greece; 27% in the EU-15, in 2007). Second, even though per capita GDP (measured in purchasing power standards for reasons of comparability) in Greece eventually converged to the EU-15 average, reaching about 90% when the crisis broke out, per capita social expenditure (also measured in purchasing power standards) hardly surpassed 80% of the respective EU-15 figure. Third, employment in public social services has been persistently low in Greece (11% in 2008, compared to 15% in the EU-15, not to mention Sweden where the corresponding rate stood at 25%).

These findings run counter to the “growth to the limits” argument, which is supported by some colleagues in the debate on the causes of the current crisis. Rather, the findings indicate that Greece under-spent in social protection in terms of its wealth. Another side of the same coin is the very low level of state revenues in Greece (37% of GDP in 2008, compared to EU-15 average of 44%) and the highly regressive fiscal policy pursued, given extensive reliance on indirect rather than direct taxes, the comparatively large informal economy, and the persistently huge tax evasion, particularly from the well-off groups. All these considerably limit the size of the social budget. Just to give you an indication of foregone revenue by the state due to black economy payments and fraud in the health sector: according to a recent study by colleagues from the Faculty of Nursing of the University of Athens, at the time of the eruption of the crisis, the sum of such payments was estimated to about 50 billion euros, an amount that equals the cumulative public deficit for the period 2003-2009.

How did the crisis and the subsequent rescue deals impact welfare in Greece? Could the crisis be an opportunity to rationalize and modernize welfare?

For the reasons I briefly discussed above, when the crisis broke Greece was characterized by a “gridlocked” social protection system. Rationalizing a fragmented and polarized system has been long overdue. The crisis brought reform to the top of the agenda of the successive “rescue-deals”. Indeed, some reforms are in the right direction. These include the amalgamation of social and health insurance funds into two single units respectively, the standardization of provisions for all socio-occupational groups, the equalization of pensionable age in the public and private sector (and between men and women), stricter conditions for early retirement, as well as a shift from derived to individual rights for women.

However, the question is whether the prevailing priorities of harsh fiscal consolidation can allow reform measures to redress inequalities by upgrading social provisions. Or, instead, a downwards equalizing attempt to a common low denominator will prevail. So far, the balance sheet of the reform indicates a downwards levelling of public provisions across the board.

However, the question is whether the prevailing priorities of harsh fiscal consolidation can allow reform measures to redress inequalities by upgrading social provisions. Or, instead, a downwards equalizing attempt to a common low denominator will prevail. So far, the balance sheet of the reform indicates a downwards levelling of public provisions across the board.

We could briefly argue that, so far, two types of reforms have taken place. On the one hand, radical institutional reforms have been introduced in the fields of social insurance and labour market policies. A wholesale pension reform strengthened the insurance principle and significantly decreased the generosity of the public scheme. Labour market reform dealt a serious blow to labour rights and increased “flexicarity”, that is flexibility without security. On the other hand, in healthcare, drastic spending cuts and receding public provision have been pursued in the name of saving the national health system. But the diminishing scope and quality of services has already jeopardized universal access. This is reflected in rising unmet healthcare needs among middle and low-income groups, for reasons such as cost, long waiting lists and distance. According to the latest Eurostat data, in 2015 about a fifth of the population with an income that falls in the lowest income quintile declared unmet needs for medical examination compared to 0.6% in Spain and 6.4% in Portugal. But even among middle-income groups, the respective figures ranged between 10 to 15% in Greece. Unmet needs among middle income groups were negligible in the other two countries.

The change in the structure of pensions led to the replacement of the single-tier public pension scheme by a multi-tier system (for a long time advocated by the OECD, the IMF and other international bodies) consisting of a basic (quasi-universal) non-contributory and a contributory pension. Given the drastic cuts in replacement rates, these two tiers will need to be complemented by funded pension schemes and private savings, in order for future pensions to ensure a decent living. But a funded, occupational tier has been very little developed in Greece so far. We also have to mention also that a considerable length of time is required for a system of funded occupational pensions to mature. Undoubtedly, inequalities of access to an occupational scheme (as well as to private insurance) will further increase poverty among the elderly and erode collective solidarity.

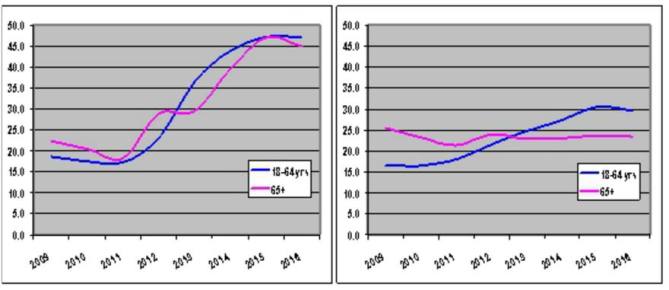

Current pensioners’ incomes have been severely affected too. Successive rounds of pension cuts – up to 40-50% for certain categories of pensioners-, in tandem with significant hikes in indirect taxes and special levies, hit disproportionally middle to low incomes. Strikingly, the justification for the successive pension cuts under the bailout deals is that pensioners are at a lesser risk of poverty in comparison with the working-age population. This may be true with regards to the relative poverty rate, which has increased faster for the working-age population, due to rapidly rising unemployment and precarious work. But the relative poverty rate is very much affected by the range of incomes, given that the poverty threshold is defined as a percentage of the median (equivalized) income. If there is a fall of incomes across the board and a diminishing range of differentials, the relative poverty figure may even decline. In this case a better indicator for the living standards would be the poverty rate measured at a fixed moment in time, namely in 2008 when the crisis erupted. This indicator clearly shows that, during the crisis, poverty increased equally sharply among pensioners and the working-age population.

Hence, any claims that there is still room for reduction in pensions, because retirees have been less severely hit by poverty is totally unfounded. It is interesting to compare Greece with Spain, which experiences equally high unemployment. In the latter country, poverty among the working-age population (measured on the basis of the 2008 threshold) increased to a lesser extent in comparison to Greece. But the most striking feature is that, in Spain, pensioners were sheltered from the adverse distributional consequences of austerity measures (see Figure below).

In a nutshell, the crisis facilitated reforms towards system rationalization (e.g. standardization of contributions and of the basket of benefits and services) but under conditions of severe spending cuts and receding public provision. Suffice it to mention as an example the reform of primary care that is underway by the Ministry of Health. Developing a unified network of public primary care units has long been overdue. As mentioned above, this was a major provision of Law 1397/1983, which never materialized. Hence any attempt to improve statutory primary care provision is in the right direction. Yet, if, as announced by the Ministry, the planned units are targeted mainly to one third of the population who experience poverty and social exclusion, universal access will be jeopardized.

You have claimed that underlying the reforms imposed by the memoranda is an attempt to redirect the Greek economy towards greater openness, through labour market liberalization and internal devaluation. Do you think this approach will bear fruit? Is there an alternative scenario for achieving this openness?

The structural reforms set forth in the memoranda aim largely at liberalization and an internal devaluation within the constraints of the Euro-area regulations, in tandem with the rationalization of public administration and the shrinking of the public sector workforce. These reforms are held to increase competitiveness and support outward-facing, market-based policies. As I stress in a recent publication, the tradeable sector in Greece has been persistently small and has failed to become a catalyst of growth. Indicatively, between 2000 and 2007, when the country experienced sustained economic growth of over 3% annually, growth had come almost entirely from the “non-tradeable” sector, namely locally rendered services and construction. This sector has been persistently larger than tradeables, which include manufacturing, agriculture and raw materials.

Of crucial importance is how greater openness will be sought when the economy recovers. Will it be sought along the trodden path of a tourism-based economy supplemented by low value-added manufacturing? Can an alternative path be followed towards a robust industrial structure and innovation system, which would tap into niche-markets for high-value added products in Europe and elsewhere? Following the trodden path implies a gloomy scenario of a race to the very bottom: wages will further shrink to match those in the neighbouring Balkan countries and the welfare state will contract to the most meagre means-tested social assistance benefits. This scenario is more or less evident in the international lenders’ approach: they advocate wages to match those of the neighbouring Balkan countries, and strongly support means-tested programmes to the neediest (e.g. a minimum income scheme) instead of universalist welfare policies addressed to the entire population.

A different scenario, of a move towards a high-skill, high value-added economy, may support a more socially embedded form of flexibilization, which combines flexibility with security. This is a “social investment” approach, which, for instance, has been a long tradition in the Nordic countries. This approach places a great emphasis on the prevention of disadvantage through quality childcare, family support, education and training. It favours the development of universal social services rather than rudimentary, means-tested provisions and balances flexibility to security. However there are no signs of a move in this direction.

The structural adjustment recipe has gravely harmed the middle and lower-class. A study carried out by a foreign research institute in 2015, has shown that middle class households lost over 40% of their wealth between 2007 and 2015. A re-composition in the occupational/employment and earnings distribution within the middle class is highly likely. This will consolidate a divide between the upper ranks of the middle class that will comfortably increase their earnings, and a large majority who will be the losers facing persistently unemployment and insecurity. This looks more like a kind of “Latin-American” future, with rigid and permanent socio-economic divides in the EU southern periphery in tandem with a bleak scenario of a two (or multi)-speed Europe, which has recently resurfaced in the debate on the future of the EU after Brexit.

What do you believe is the future of the welfare system in Greece? How will it affect the middle classes and their political alignment?

In a scenario of increasing social polarization and sharp contraction of the middle class it is highly likely that the individualization of risk will prevail, under conditions in which great strains will also be exerted on the traditional family model of care provision. A move towards a mass-supported comprehensive, rights-based welfare state is not on the horizon. Neither are there any signs of reinvigoration of “Social Europe” that could have a positive effect on the welfare state future in the country. The recent effort by the Commission to develop a European Social Pillar has not so far contributed to a refocus on the EU’s social dimension. It remains a rather rhetorical proclamation. Besides, the ongoing refugee crisis fuels political divisions between and within EU countries and highlights the big obstacles towards interstate solidarity and adherence to the values of “Social Europe”.

Of significant importance is the sharp decline in trust in the political establishment (including the trade unions). This brought the party system in a deep flux in Greece. Support for the two main political parties (the right-wing New Democracy, and the centre-left PASOK), which have alternated in power since the restoration of democracy in 1974, reached record low levels, and new parties, both on the far-right, centre and left have emerged. It is difficult to predict how mass social discontent will be channeled at the political level. When in opposition, SYRIZA’s platform for a fightback approach (against austerity) garnered considerable support that propelled it to power. However, the harsh reforms of the third bailout deal of July 2015 and the refugee crisis are increasing disillusionment. Whether SYRIZA will continue to be a credible voice to address discontent (and deliver on its promises) is an open question. It is quite likely, though, that disillusioned and impoverished strata may switch political support to right-wing populism. This will play the role of an “exhaust valve”, which, albeit, will intensify institutional frustration in the country.

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi

Read more about the Greek welfare state and its characteristics via Rethinking Greece interviews: Rethinking Greece: Christos Papatheodorou on the impact of austerity measures, poverty and social protection; Rethinking Greece: Manos Matsaganis on the Greek welfare state and its under-protected outsiders

Read also Maria Petmesidou’s recent paper “Can the European Union 2020 Strategy Deliver on Social Inclusion?” (Global Challenges – Working Paper Series, June 2017)