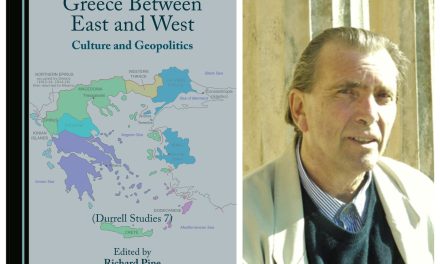

Dimitris Papanikolaou is Associate Professor in Modern Greek and Fellow of St. Cross College, Oxford University, UK. Papanikolaou’s research focuses on the ways Modern Greek literature opens a dialogue with other cultural forms (especially Greek popular culture) as well as other literatures and cultures; the other important strand of his research focuses on queer theory and Greek queer cultures.

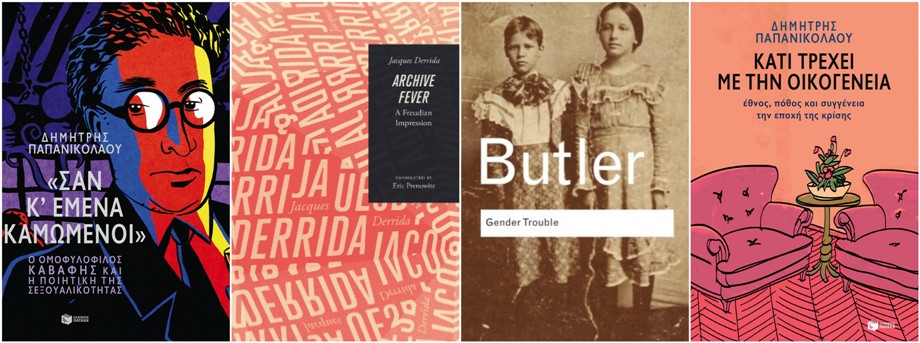

Professor Papanikolaou’s book on C.P. Cavafy‘s homosexuality and the poetics of sexuality (“Made just like me”: The homosexual Cavafy and the poetics of sexuality“, Published in Greek: “Σαν κι εμένα καμωμένοι. Ο ομοφυλόφιλος Καβάφης και η ποιητική της σεξουαλικότητας”, 2014) has been widely discussed in Greece by literaly critics and Cavafy scholars, while his latest monograph (“There is something about the family: Nation, desire and kinship at a time of crisis”, Published in Greek: “Κάτι τρέχει με την οικογένεια: Έθνος, πόθος και συγγένεια την εποχή της κρίσης”, 2018) is largely an extended comment on the increased production of cultural texts on the dysfunctionality of the Greek family.

Papanikolaou has also been a regular contributor of political commentaries in Greek in Unfollow leftwing monthly review, as well as in Enthemata weekly. His next big projects include: a book titled Greek Weird Wave: A Cinema of Biopolitics; and a longer project provisionally titled ‘Queering Hellas: Movement, sexuality and the place of Greece between the wars’, which looks into expressions of queer desire by writers who moved in and/or out of Greece in the 1920s and 1930s.

Dimitris Papanikolaou spoke to Rethinking Greece* about his work on C.P. Cavafy from the perspective of queer theory; how Greek art under austerity is becoming political in unpredictable ways; Greek exceptionalism and his idea of a minimal or a ‘strategic exceptionalism’ as a useful weapon; the narrative power of the “Holy Greek Family”, as well as the concept of the family as biopolitics and the term “archive trouble” he develops in his latest book. Papanikolaou also addresses the huge impact that the new LGBTQI and anti-racist legislation has had and how the LGBTQI movement in Greece now has the power to be even more intersectional and more inclusive. He finally advocates for the support of departments of Greek language and Literature as hubs that can further foster what is already happening: a real resurgence of wider Modern Greek Studies and “a radical reappraisal of what it means to be Greek in a globalized, glocalized, overmediated, contingent, inconsistent, precarious and simmering world”:

Your work engages with ‘Cavafy and the discourses of sexuality’. Can you tell us a few words about the importance of sexuality in Cavafy’s work and its contemporary relevance?

Many years ago I decided to address what I had felt as a lacuna in Modern Greek Studies, indeed, its most obvious lacuna: to tackle the word of C.P. Cavafy, a well-known poet of the early 20th century who wrote about homoeroticism and homosexuality in ways that were groundbreaking for his times, from the perspective of queer theory and the history of sexuality. In the years that it took for this project to take concrete shape, I realized that it had two separate, important, facets.

One was the new perspectives it could give to the actual poems, as well as the comparative dimensions it was opening them up to. Our slowness in addressing the queer dimension in the work of one of the major figures of Modern Greek letters, had also meant an unease in bringing him closer to authors such as Proust, Whitman, Colette, Gide, Rachilde, but also John Addington Symonds, Edward Carpenter, the Uranians and so on. It had also meant a certain unease in synchronising our readings of Cavafy with debates and developments about writing and sexuality, queer modernity and the autobiographical expression of non-normative sexuality. Yet they were all there: the importance of Cavafy’s work for modern queer cultures; its links to other archi-texts of that tradition; its potential dialogue with more subcultural texts and contexts (such as the Roman d’un inverti, the turn-of-century sexological writing, or the photography of Von Gloeden); last, but not least, its spectacular ability to anticipate newer debates about closeting, sexual citizenship, queer time, cultural dissidence and its impact on sexual identity and desire.

One was the new perspectives it could give to the actual poems, as well as the comparative dimensions it was opening them up to. Our slowness in addressing the queer dimension in the work of one of the major figures of Modern Greek letters, had also meant an unease in bringing him closer to authors such as Proust, Whitman, Colette, Gide, Rachilde, but also John Addington Symonds, Edward Carpenter, the Uranians and so on. It had also meant a certain unease in synchronising our readings of Cavafy with debates and developments about writing and sexuality, queer modernity and the autobiographical expression of non-normative sexuality. Yet they were all there: the importance of Cavafy’s work for modern queer cultures; its links to other archi-texts of that tradition; its potential dialogue with more subcultural texts and contexts (such as the Roman d’un inverti, the turn-of-century sexological writing, or the photography of Von Gloeden); last, but not least, its spectacular ability to anticipate newer debates about closeting, sexual citizenship, queer time, cultural dissidence and its impact on sexual identity and desire.

The second element related to a potential queer reading of Cavafy, had to do with the specific politics, within Greek academia and institutional criticism, that had precluded such a reading, or had tried to preempt it as narrow and unworthy. My work alongside that of other scholars stood against this tradition and tried to critically unmask it as a suppressive genealogy, fully recognizing that this was not only a critical, but also a political project. Apart from the enthusiastic reviews (of which there were plenty), I received, of course, also virulent, vituperative comments and attacks, unfortunately not all of them impervious to the homophobia that they were always fast in announcing that they had denounced.

“The Greek arts scene flourishes in midst of economic crisis” has been a common understanding/scheme/cliché but how did the economic crisis really affect art and artists in Greece?

Art needs money and institutions – and Greece has, recently, been running low on both. On the other hand, art needs challenges and an environment where its interventions would matter: of that, Greece had plenty.

This is how Athens became, for many “the new Berlin” (a term that I personally dislike, for various reasons), this is how some of the most challenging new European art (especially in performance, in cinema and in graffiti) started coming out of Greece, this is how some of the best debates on culture and politics took place in Greek fora, often with the participation of internationally renowned intellectuals who came to Greece not only to speak, but also to hear and listen.

Not that all this surge in interest came without its problems. The Documenta 14 exhibition, for instance, curated by Adam Szymczyk with an impressive series of public programmes curated by Paul Preciado, became a contentious arena, critiqued by many in Greece as ‘orientalist crisis chic’, and defended by others (including myself) as a very productive opening of the Greek scene (including the less heard arguments of the Greek political debate) to the world.

In poetry, the successful English collections on “Poetry and the Crisis” (for instance, the one edited by Karen Van Dyck for Penguin, and by Thodoris Chiotis for Penned in the Margins), found an uneasy reception in Greece, with authors arguing that they are misrepresenting the actual currents of Greek poetry.

And Greek cinematographers, living through one of most internationally accommodating periods for Greek film, never felt at ease with the label ‘Greek Weird Wave’ that was imposed on to their work, neither were they happy with the immediate link that critics seemed to establish between the ‘Weird Wave’ and the sociopolitical context of the Crisis.

All this points to anxiety about being pigeonholed and marginalized, an anxiety often expressed by artists and cultural agents in the periphery. It also points, however, to an unquestionable reality: Greek art is now becoming political in ways that sometimes supersede specific movements or intentions; it participates in an intensive politics of everyday life under austerity and heightened biopolitical governance, even when/where this is not its absolute choice.

Exceptionalism seems to have been the dominant narrative not only for Modern Greek Studies but also for Greek political science, history and more recently, political economy. Should we question its academic/political agenda and rethink Greece beyond its discourse?

More than a decade ago (I think it must have been 2006 or so) two colleagues from Princeton (Constanze Guthenke and Effie Rentzou) and I, all in the early stages of our careers, started a project under the self-evident title ‘Questioning Greek Exceptionalism’. For us the target was obvious: we had been trained by humanist and national(ist) education in thinking that Greece (ancient and modern) was somehow exceptional; yet when we searched for the tools to undermine that type of cultural exceptionalism, we were also faced with theories and analyses that, again, treated Greece as an exceptional case (even in its “belatedness” or “anti-modenity” and ethnonational fixation). We should have known better; it is one thing to critique traditionalists for exceptionalism, and quite another to wag one’s finger at everyone (including oneself). The project, even though discussed at the time, failed to gain traction.

I was reminded of that experience when more recently Greece was, on the one hand singled out in a global financial crisis as the eye of the storm (and Greek society was singled out as the sole reason for its own financial woes), and on the other, Greek political science and sociology joined the discussion arguing that there is something exceptionally different in the case of Greece (a strategy shared by commentators on both sides of the political spectrum).

Of course we need to rethink Greece beyond these wildly exceptionalist frames; we ought to see recent events as well as social developments in a wider context and drawing the widest possible parallels.

Having said that, and based on my experience as a cultural critic, I have also reached the conclusion that there is a level of analysis, let’s call it minimal or strategic exceptionalism (echoing Gayatri Spivak’s concept ‘strategic essentialism’), that can be useful and, indeed, a necessary weapon in putting forth one’s argument in the global arena. Exceptionalism, even though always problematic when it becomes dominant ideology, could perhaps, in its minor and strategic versions, also turn into a tool for cultural resistance and speaking out, a creative force for marginalized voices and disavowed cultural archives. There is some sense, in other words, in showing the exceptional impact the recent crisis has had on Greek society and culture, while also looking for parallels and points of comparison, and critiquing any effort to create out of that exceptional situation a dominant and stagnant ideology.

Speaking of Greek exceptionalism, is there something exceptional about the Greek family? In your latest work, the monograph ‘There is Something about the (Greek) Family’, you talk about the increased production of cultural texts on the dysfunctionality of the Greek family, especially since the eruption of the crisis. Why do you believe Greek artists have turned to the family, and have done so in such a way?

Early in my new book, I felt the need to address this issue, the ‘exceptionality of the Greek family’, or its opposite, the possibility that, in the final analysis, the Greek family might not be exceptional at all. I was confronted with two discourses, both solid and culturally significant. On the one hand, a long tradition that insists that the Greek family (in the mainland, in the diaspora, in the real conditions of people’s lives as well as in their fantasies about them) is indeed exceptional; too patriarchal but also with a very strong role for the Greek mother (who often is the one fighting to safeguard the rigid traditions of the family, including its masculinist bias); too firmly based on extended kinship networks of help and support, but also extremely oppressive; an institution of excellence and national pride, but also the hotbed of nationalism and national intransigence. At the same time, on the other hand, there were those who claimed that all these characteristics are to be found also in other family traditions too, and most of them, perhaps, all over the world.

I address those two opposing narratives in my work, and see both their insights and their limits. There are, obviously, specificities in the Greek family (including historical specificities for the role played by extended kinship networks in Greek cultural, public and political spheres, as well as internal differences in what we sometimes too easily conceptualize as ‘the Greek family’). And there are also similarities with the kinship structures elsewhere in the world, starting from the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean basin.

However, an axiom I have followed in my work is that, even when we realize that some of the characteristics of the Greek family are, in the final analysis, not so exceptional at all, it is still analytically productive to track them and discuss how much cultural work they have been doing as exceptional. What I mean by this is that even the widely held narrative about the exceptionality of the Greek family (what in Greece in popular discourse is often referred to as ‘the Holy Greek family’ – η Αγία Ελληνική Οικογένεια) can be powerful and productive as a narrative, in that it frames institutional analysis and policies, deeply held beliefs and ideologies, political positions and practices.

It is also for this reason that I have found recent Greek cinema so fascinating. In many of the films of the Greek Weird Wave, you see the effort of directors to speak about the wider issue of family oppression and violence, sometimes in an obviously allegorical tone that is trying not to be limited by any Greek specificity. Yet, the reception of these films, still, in Greece and abroad, happened in the context of the ‘exceptional Greek family’. The families in Yorgos Lanthimos’s Dogtooth and Alps, or in Athina Tsangari’s Attenberg and Alexandros Avranas’s Miss Violence, are not specifically Greek (and they try not to be specifically Greek, the setting of these films deliberately not recalling recognizable Greek settings). Yet these directors were called upon time and again, by Greek and international commentators, to discuss their films as a commentary on the Greek family specifically; and, what is important, more often than not, they all decided to play ball.

The Greek paterfamilias appears often in these cultural texts as an oppressive, almost tyrannical figure. What about the infamous figure of passive-aggressive, almighty, loving but overbearing and emasculating Greek mother? This dominant “Greek mother” is a very popular figure in popular discourse, however she is largely absent from these cultural texts, or shown as powerless, silent and almost always overpowered by the father. Could you comment this disparity between popular discourse and cultural texts?

Contrary to expectation, these recent cultural texts are more invested in thinking about power dynamics, control and biopolitics, than about a sociological exploration of the specific gender and affective structures of Greek kinship. In other words, they are not performing a sociology, but a political economy of the Greek family. They are also, as cultural texts, active in the Greek public sphere, inciting discourse, producing new modes of engagement and critique. This might explain the point you raise, the absence of ‘the domineering Greek mother’ in some films, novels and theatre in Greece of the last decade. There have been important exceptions, of course (eg. films such as The Matchbox by Yannis Economides), however what you point out might be right, it is mainly the tyrannical father that takes centre stage in many a Greek cultural text of the last decade.

What for me is the most intriguing about these cultural texts is that they turned towards complex modes of allegory when everyone was expecting them to offer realistic portrayals. For this reason, their obsession with tyrannical (or undermined) father figures seems understandable: they want to show that the centre (of a symbolic, a national, a cultural, an affective system) does not hold any more.

It is interesting, within this context, to review what happens in the film Miss Violence: when the father’s abusive tactics get out of hand, it is the mother who plots to kill him; in the last scene, however, we see her fully assuming his position after he’s gone, as she once again orders the members of the family to lock the door of their apartment and stay inside, now under her power. Mothers can be patriarchal too (and this does not mean that they cannot also be resistant to patriarchy).

In your book, you talk about the family as a biopolitics and also introduce the term “archive trouble” in the context of studying family histories. Can you expand on these concepts?

Indeed, biopolitics and archive trouble are the analytical foundations of the argument in my book. The first is the well known concept popularized in the last decades thanks to the work of Michel Foucault and the criticism that came on its heels. Biopolitics (the politics of/over life) is a concept that helps us better understand how the contemporary world is governed, how the lives of individuals and of populations are organized, projecting liveability to specific groups of people and condemning others to a slow death, reorganizing the protocols of what it means to be human, which humans can have what type of protection and access to supposedly common human achievements (such as medicine and health care, education, freedom of movement, clean water and sanitation, ‘human rights’) and who will be deprived of them or given a different, ‘lighter’ version. Crucially, biopolitics also organizes not only forms of governance and the development institutions, it also frames self-governance, it impacts on the ways we internalize doctrines, ‘economic plans’, ideologies, body images, psychosocial demands, limitations, prohibitions and incitements. It is not an exaggeration, therefore, if we claim, as so many of us do in our work, that we live in a culture of biopolitics; that we speak from within an intense biopolitical present.

I coined the term Archive Trouble, as a result, in order to describe a larger apparatus, a certain mode of understanding, of reacting, of making culture within, and making do with, this biopolitical present. It is an obvious pun bringing together the recent interest in archives and archivality (part of which stemming from Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever), and the post-Judith Butler thinking of the performative constitution of gender and sexuality encapsulated in seminal works like Gender Trouble. Archive Trouble is a constant questioning about our forms of participating in the political present, through a parallel inquiry about the past and its cultural and ideological impact. Archive Trouble is the effort to reconstitute the archival at a moment of crisis, an effort that, more often than not, becomes evident through the emergence of embodied acts, of bodies that show anxiety, show affective attachment and emotional release, show the explosive potential of a present experienced in the need for embodied counter-memory and radical understanding.

Archive Trouble is a modality that we witness, expansive and engaging, in Greece today. I have documented it in art, in disparate and diverse examples, which, however, show some common features: their pervasive feeling of urgency; an iconoclastic return to the past; a dense biopolitical thinking; a central role for the body in/as performance; an attempt to create, out of all this, a new political and widely participatory art in the present. Archive Trouble performs genealogical exercises and issues constant demands for a history of the present, one that foregrounds our intersecting demands and identities, our intersectionality, as present continuous; our need for historicization as present archival; our expansive citizenship claims as present processual; and our multilayered precarity as present biopolitical.

In the four years since SYRIZA has been in power, we have seen progressive legislation being passed on sex and gender issues, such as the right of same-sex couples to form a civil partnership and to foster children and transgender people’s right to change their legal gender freely. Will these changes function to remove some of the deadlocks of the Greek family? What do they mean for the LGBTQI / human rights agenda and the expression of ‘other’ sexualities in times of crisis?

In many ways the passing of progressive legislation on human rights, including LGBTQI rights, and the fight against racism and entrenched forms of misogyny and homophobia, became for SYRIZA the platform to prove itself as a left-wing government. Let us not forget that at the same time other decisions the same government implemented, mainly related to austerity measures and the undermining of workers’ rights and union power, have been clearly anti-Left. That said, one should not underestimate the huge impact the new LGBTQI and anti-racist legislation has had, not only on people’s dealings with officials and the state, but also in everyday life, on public opinion, in the public sphere. Greeks are now more cognizant of homophobia, more intolerant of the various forms of racism, more alert to supporting victims of bullying. Internalized and institutionalized (esp. by the Greek church) homophobia and chauvinism still exist, of course; and forms of extreme nationalism are, once again, on the rise.

Yet, as someone who has often offered opinion and has discussed LGBTQI legislation in Greece in various capacities, I have to admit that I had not expected so much to happen in so little time (especially on issues like homoparentality and gender identity declaration). This puts the LGBTQI movement in Greece now in a very advantageous position: it now has the power to be even more radical and more intersectional, more inclusive, more demanding. The rights of migrants (including queer migrants), the rights in the workplace (which include gender rights in the workplace), the rights to assembly as well as the rights to free education and healthcare (which affect everyone, and LGBTQI people know that intimately), the fight against all forms of racism, are all today resurfacing as the new (who would have thought!) fronts to fight, and I can’t see why they shouldn’t frame the central demands of the LGBTQI movement too. And of course, let us not forget the obvious: the LGBTQI movement is also a crucial agent in the fight against the recurrence of racism, ultra-nationalism and fascism which we see today in Greece, after 10 years of intense crisis.

Yet, as someone who has often offered opinion and has discussed LGBTQI legislation in Greece in various capacities, I have to admit that I had not expected so much to happen in so little time (especially on issues like homoparentality and gender identity declaration). This puts the LGBTQI movement in Greece now in a very advantageous position: it now has the power to be even more radical and more intersectional, more inclusive, more demanding. The rights of migrants (including queer migrants), the rights in the workplace (which include gender rights in the workplace), the rights to assembly as well as the rights to free education and healthcare (which affect everyone, and LGBTQI people know that intimately), the fight against all forms of racism, are all today resurfacing as the new (who would have thought!) fronts to fight, and I can’t see why they shouldn’t frame the central demands of the LGBTQI movement too. And of course, let us not forget the obvious: the LGBTQI movement is also a crucial agent in the fight against the recurrence of racism, ultra-nationalism and fascism which we see today in Greece, after 10 years of intense crisis.

What is the future of Modern Greek Studies outside Greece? In what terms to you think scholars and students (re)approach the Greek path to modernity after the crisis, in the UK and internationally?

Since I was a graduate student, the major complaint in our field was the ‘imminent death of Modern Greek Studies’. All of us, scholars of CompLit and ModGreek Studies, have at some point in our careers written articles with titles such as ‘the need to reinvent Modern Greek Studies’, ‘the crisis of Modern Greek Studies’, ‘save Modern Greek Studies’, ‘Modern Greek Studies at a crossroads’ and so on. And it is true that some of the old and traditionally acclaimed departments of Modern Greek Studies outside Greece have closed down in recent years, or have had a difficult time remaining open.

However, at the very same time, our professional organizations grow; academics writing and teaching on Greek subjects take illustrious chairs all over the world; new academic journals (such as the Journal of Greek Media and Culture) become the platform for publishing new interdisciplinary work and the older and established journals in the field are read more than ever; and never before was there such an interest in Modern Greece by publishers, academic fora and interdisciplinary research bodies. To keep complaining about the ‘decline of Modern Greek’ would just mean that we focus on a part and keep failing to see the whole picture.

Let it be clear: What is under threat today is the existence of specialized departments of Greek language and Literature, and these are precisely the departments and centres that need institutional and financial help. The reason is simple: it is precisely because Modern Greek Studies as a whole is in such a dynamic state at the moment, that it is also in the best interest of everyone to support these few more specialized departments of Greek language, literature and history, since they act as the necessary hubs for the field at large. They can nurture new talent, become the centres of publishing and academic debate on Greece, and create important ports of contact for academics working in Greece. If we focus on supporting these few centres for Greek language and literature around the world, then we can be free to celebrate what is also happening recently: the real resurgence of the wider Modern Greek Studies, a genuine reinvigoration of analytical debate on Greece and its diverse paths to modernities, as well as, for the first time, a radical reappraisal of what it means to be Greek in a globalized, glocalized, overmediated, contingent, inconsistent, precarious and simmering world.

*Interview by Julia Livaditi and Nikolas Nenedakis

Watch Dimitris Papanikolaou lecture on “New Queer Greece?” (Enjoy (y)our State of Emergency: art and activist strategies in times of crisis, 2014):

Read also via Greek News Agenda: New Queer Greece: Performance, Politics, Identity; Rethinking Greece: Stella Belia on Civil Partnership Rights, LGBT claims and human rights agenda in times of crisis; Maria Yannakaki, Secretary General for Human Rights on the legal recognition of gender identity