Henriette-Rika Benveniste is Professor of European Medieval History at the Department of History Archaeology and Social Anthropology of the University of Thessaly. She studied History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and completed her doctoral studies in Medieval History at the Université de Sorbonne (Paris I, Panthéon). Her research interests include Historical Anthropology of the Middle Ages and Jewish History and Historiography.

Professor Benveniste has been the Academic Head of the Project: “From Between the Wars to Reconstruction (1930-1960). The Experience of the Jews of Greece in Audio-Visual Testimony”. (Database of Greek-Jewish Survivors’ Testimonies, University of Thessaly). Her recent book “Those Who Survived: Deportation, Resistance and Return of the Jews of Thessaloniki in the 1940s”, (in Greek: Αυτοί που επέζησαν, 2014; in German: Die Überlebenden. Widerstand, Deportation, Rückkehr. Juden aus Thessaloniki in den 1940er Jahren, 2016; English and Hebrew translations forthcoming) received the National Book Award for Promoting Dialogue on Social Issues in 2015.

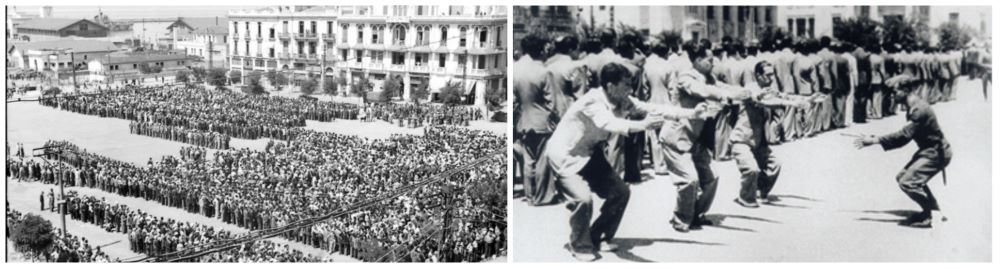

Rika Benveniste spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the long process of making Greek Jewish communities visible again in Greek history and the Greek public sphere after decades of silence, the need for research on Greek Jewry that challenges Greek exceptionalism and espouses a transnational perspective ― as “the history of the Jews of Greece is a Jewish history, a Greek history, a Mediterranean history and a European history all at the same time”. Regarding the social and cultural diversity of the Jewish population of Thessaloniki, she points out that their political beliefs run the whole spectrum; from those who advocated assimilation to Greek language and culture, to Zionists with visions of a national homeland in Palestine, to Liberals and Socialists leading the worker’s movement of the city. Benveniste stresses the importance of encouraging complex narratives on the Shoah, instead of simplistic ones that ignore the indifference or the betrayal of collaborators, or moralistic ones that emphasize a generalized abstract “shame”, while omitting the fact that some were really guilty, in very precise and concrete ways.

Professor Benveniste emphasises that, while the extermination of the Jewish communities was a Nazi project, its implementation “was, at every step, relative to the obedience of Jews and non-Jews, the collaboration of the politicians and local authorities, the passive or active support of the Jews’ neighbours, the desire of the victims to gain time and their room for action”. Finally, she asserts that studying Greek Jewish history may serve as a “referential framework” for developing historical sensibility and a critical mind, in order to resist both the racist and antisemitic discourse in Greece as well as the rise of the extreme right and the alarming rate of normalization of historical and political revisionism that is taking place all over Europe:

Jews were almost invisible in Greek history, until the 1990s, when we witnessed what you have described as the ‘coming out’ of Jewish history. Why do you think deliberations on Jewish communities and the Shoah in Greece had been absent in Greek historiography for so long?

In the article you mention, I was pointing to the fact that, for a very long period, Greek historiography had erased Jews from the Greek national entity -considered to be homogeneous. To a reader of Greek history Jews were “invisible”. When Jews, occasionally, appeared in the Greek history of the Ottoman period or the Greek nation state, they were perceived as a force disrupting the nation. There was practically no historical research conducted outside the Jewish milieu, and it was conducted mostly outside Greece. On their part, historians of Jewish history were mostly interested in the religious and intellectual aspects of the history of Jewish communities.

The interest in Greek-Jewish history coincides with the breaking of the silence on Shoah. The absence of Jews in the Greek public narratives of the post-war period was determined by a will to silence the destruction of Greek Jewry. However, we should not dismiss the fact that this was by no means a Greek particularity. In the political climate of the Cold War, German atrocities were downplayed, while the scope and the significance of the Holocaust was not understood. The victors of the Second World War were unwilling to realize that the war was not over for the Jewish survivors, whose lives had been saturated by the loss of their families and their communities. In countries like Netherlands and France, the experiences of Jewish victims were subsumed into the narrative of national heroism that pervaded postwar reconstruction. In Germany, deep-seated feelings of resentment towards the post-war political and social environment accompanied oblivion and silence about the crimes and a too quick will to leave the past behind.

In Greece, political persecutions during and after the Civil War were coupled with censorship on the memory and history of the Resistance and the genocide of the Greek Jews. The right-wing victors of the Civil War imposed silence because Greek collaborators of the Nazis were quickly incorporated into the anti-communist state and their crimes remained unpunished. Later on, the 1967-1974 military dictatorship and its slogan “Greece of Christian Greeks” tried to impose the idea of an exclusively Christian Orthodox character of the Greek society. In other words, beyond the moral and material annihilation, the haunting feelings of loss, the pressing demands of rebuilding a “new life”, the unwillingness to listen to their sufferings -characteristics which were common to survivors all over the world- Greek Jewish Holocaust survivors faced also the terrorism and censorship exercised by the victors of the Civil War.

The first chronicles of the Occupation and the deportation, at the crossroads between history and testimony, were published by Jews in the first post-war years. However, these first attempts to write the history of the Holocaust in Greece remained locked inside the Jewish community. Again, there was no willingness to hear the Jewish sufferings when the victors of the Civil War had imposed silence. The silence on the destruction of Greek Jewry imposed a silence of the communities’ pre-war history as well.

Historiography turned to the study of the destruction of the Greek Jewish communities with a delay. It was as late as 1986, when a book by Hagen Fleischer on the Nazi Occupation (“Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte: Griechenland 1941-1944 -Okkupation, Resistance, Kollaboration”, translated as “Στέμμα και σβάστικα” in Greek) devoted detailed chapters to the Holocaust; this was followed in 1993 by Mark Mazower’s book “Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44”. In 1996, the Society for the Study of Greek Jewry organized a conference which dealt with the Jews of Greece under the Occupation; its acts were published in 1998, edited by me.

The breaking of the silence on the Shoah on an international level had sparked interest in Greek Jewish communities’ past. Moreover, during the 1990’s, the voices of Greek Jewish survivors were heard in a new environment dominated by the rise of identity politics. Hesitantly, Greek Jewish communities adopted a policy of cultural presence and turned towards the surrounding society. Projects of collecting and publishing oral and written testimonies were a major aspect of that decade and Fragiski Abatzopoulou’s work was an important contribution in this field. In a new space of public history, the collective memory of new comers or older ethnic groups met with official history.

The first international conference on “Jews in Greece. Questions of History in the longue durée” took place in 1991 and its proceedings were published some years later. The conference was held in Salonika and had been organized by the “Society for the Study of Greek Jewry”, which remained active for about ten years. The “Society” was run mostly by academics and it had absolutely no institutional basis. This first conference aimed at showing the complexity, the continuities and the ruptures in a long Jewish presence in Greece. It opened the new historiographical era in which the Jewish past became more visible. Up to that time, historians provocatively ignored Salonika’s Jewish past. Rena Molho’s book on the particularities of the Jewish community of Salonika (Οι Εβραίοι της Θεσσαλονίκης 1856-1919) published in 2001 was the result of the first systematic research on Salonika’s Jewish past.

After this “coming out”, Jewish history has become more visible in the Greek public sphere, with the proliferation of academic projects and relevant publications. What are the dominant narratives that have emerged and what has been neglected?

It has been demonstrated by Odette Varon-Vassard and other scholars that Jewish presence has become more visible in the public sphere with the erection of monuments, the organization of commemorative events and educational projects. This is partly due to the international conjuncture of the rise of identity politics and memory studies, which has also influenced Greece. It is also true that since 2000, people from various disciplines contributed with their work and queries in mapping the Jewish presence in the Greek past. Publications in the field of history have proliferated and we may even say that Greek Jewish History has gained some legitimacy.

This has been the result of debunking old dominant narratives regarding Greek society as culturally and ethnically homogeneous, of studying antisemitism in historical terms, of revealing differences between various traditions in the Greek Jewish communities, of working on sensitive subjects of the Holocaust such as the Collaboration and so on. Holocaust studies and memory studies prevail. This is an international trend but the hesitation in studying earlier periods is also related -though only in part- to the difficulties of accessing sources composed in different languages and researching archives located in different places.

I believe that it is too early to judge the historical work produced up to now. It is nevertheless necessary to reflect on the current historiographical situation in order to see the research’s lacunae, constraints, stakes, and perspectives. The accumulation of historical publications does not necessarily correspond to an advancement of historical knowledge or understanding. Much of this historical work is presented in meetings which stand halfway between academic events and memorial practices, between research and political conformity, between sensibility and the needs of funding an academic career. The quality of the works varies greatly, going from narratives full of platitudes (sometimes erroneous) to deeply researched, original and thought-provoking contributions. Unfortunately, monographs are still rare, but some PhD dissertations, which are now under preparation, will probably make up for this scarcity.

If you ask me what directions research should take, I would insist on the need to encourage monographs that would take into account regional factors, challenge Greek exceptionalism and espouse a national as well as transnational perspective. The history of the Jews of Greece is a Jewish history, a Greek history, a Mediterranean history and a European history, all at the same time. The research should engage with the history of the Sephardic and Romaniote Jews in the Ottoman era (today mostly conducted outside Greece) and the Greek state. A new history of the Jews of Greece under the Occupation should take into account the diversity of the history of the Greek Jewish communities and attempt to integrate it into the context of the European war. Maria Kavala’s work on Salonika and the fate of the Jews during the Occupation and in the aftermath goes in this direction. Research would benefit by seeking the continuities and raptures between the Interwar years, the Shoah and the post-war period.

We still lack bottom-up approaches; we still need to appreciate Jewish communities as multi-class entities, composed by men and women, who interacted with each other, with non-Jews and with the state. We have to examine the communities’ heterogeneities and the cultural changes they went through. We still have to study the complex Jewish-Christian relations and not only antisemitism, while at the same time we need to historicize it, to avoid a “lachrymose perception” of Jewish history. Archives wait to be researched. We have to keep in mind that research has its own slow rhythms and work has to be carried out less loudly and independently of the mass media’s own purposes. Last, but not least, the practice of historical research should go hand in hand with a critical stance towards public history.

You have said that “it is very difficult to speak in general terms about the extermination of the Jews of Greece during the Occupation.” What were the particular elements of the persecution and extermination of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki?

Nazi ideology was responsible for the Holocaust, but the extermination of European Jews is strongly related to the war’s progression, the attitudes of their fellow citizens, the role of the Resistance, the different choices that Jewish groups and communities faced. The deportation and extermination of the Jews was a German project, but without local collaboration the numbers of the deported would have been lower. There are questions which are hard to answer: What information existed and how wasit perceived and evaluated in a universe of fear or hope? What were the possibilities for protest and expression of solidarity on the part of the fellow citizens? In Greece, the three occupation zones (German, Bulgarian and Italian) had determined the temporality of the deportations. When the Germans invaded Greece, the decision to exterminate the Jews had already been taken, and in procedural terms it was formulated in January 1942 at the Wannsee Conference. However, anti-Jewish measures increased only gradually and the deportation of the Jews of Thessaloniki began only in March 1943. At that time the Resistance movement was only in its beginning. Let us recall that Athens’ Jews were deported one year later, in March 1944, and the deportation of the last Jews of Greece took place in the summer of 1944, when the Reich had already collapsed.

The case of Thessaloniki, with its large Jewish community and extremely high rate of losses, has -partly rightly- dominated the study of the Holocaust in Greece; it still presents unexplored aspects. The implementation of the German measures was, at every step, relative to the obedience of Jews and non-Jews, the collaboration of the politicians and local authorities, the passive or active support of the Jews’ neighbours, the desire of the victims to gain time and their room for action. Institutions, networks, rivalries and solidarity played a dynamic role.

In the introduction of your book “Those who Survived: Deportation, Resistance and Return of the Jews of Thessaloniki in the 1940s” you write that your research is “a methodological proposal for a new history of the extermination of the Jews of Greece”. Could you expand on that?

In my book, “Those who survived” as well as in “Louna. An Essay of historical biography”, I make some methodological assumptions. When you think about it, survivors’ trajectories are always extraordinary. Nothing is normal in the Shoah and every story of survival is exceptional. I don’t dismiss the possibility of documenting Holocaust by testimonies, nor the insight provided by a witness’s story.

However, to what extent can one accumulate stories that are always exceptional and normal at the same time, each one with its own particular sufferings, cruelty, compassion and accidental encounters? Do we risk falling into the trap of a litany of repeating motives that crushes us? Are we motivated by a residue of positivist illusion that drives us to record all cases exhaustively? How does this influence historical understanding? It seems to me that an answer lies in a historiography that seeks a narrative of a collective history in which we will manage to integrate, in a meaningful way, the stories of cases that diverge.

The modalities and the suffering of deportation are not limited to a single theme with variations. Our understanding depends on our ability to take into account the differences in space and time of the persecution, the need to approach our subject by reducing the scale of observation, only to rethink again on a macroscopic level; a focus that shifts from collective Jewish destiny to the observation of a group that shares a common experience or to individual trajectories (sometimes within the same family) allows us to better understand the spectrum of constraints and risks, dilemmas and choices, while remaining inscribed to a much larger historiographic body. Archival documents, oral archives, private documents: from the administrative bounds to the common experience, from the reconstruction of a collective story to the individual case and then back to the collective. The Holocaust, a German crime conducted on a transnational level, reduced the importance of national borders. If we want to imagine a total history of the Shoah, the postwar traces of a whole generation of Jewish survivors should be taken into account as well.

Thessaloniki’s Zionist associations in the 20s and the 30s tried to forge a new Greek-Jewish identity, a “supplementary nationality”, sustained by the belief that one could be both “a good Jew and a loyal Greek”. However, these efforts were cut short by the WWII and the Shoah. How has Greek-Jewish identity evolved since then?

During the Interwar period Greek governments recognized the Jewish community of Salonica as an institution, accepting its political autonomy and its members’ equality before the law. The Jews of Salonika had initiated the process which led to the law that formalized the structure and rights of Jewish communities as religious minorities. Before the war, almost all the Salonika Jews observed the Sabbath and the religious holidays. However, this did not make the Jewish population socially and culturally homogeneous nor did it reduce their self-understanding to religious terms.

Language, for instance, played an important role. The old aristocracy spoke Italian; the educated bourgeoisie had adopted French; the language that united them all, rich and poor, was Judeo-Spanish, the Castilian of the immigrants from the Iberian Peninsula. Proletarians and petty merchants lived in poor neighborhoods, at the 151 and the Regie Vardar, in wooden houses with a common courtyard. Rich merchants lived in imposing edifices at the suburb of Campanias. The community was characterized by cultural variety and social conflicts. There were Jews faithful to tradition but open to modernity, and Jews covering the whole spectrum of political tendencies and currents: those who advocated assimilation to Greek language and culture, Zionists with visions of a national homeland in Palestine as well as Liberals and Socialists leading the worker’s movement of the city. All this has been extensively discussed in the works of scholars such as Minna Rozen and Rena Molho.

In other words, Zionism was only one among the different ideological tendencies and cultural associations that characterized the Jews of Thessaloniki. It was formed in communication with the international Zionist movement, in opposition to competitive currents that penetrated the Jewish population, in opposition or in harmony with the new Greek nation-state and responding to the social and economic conditions as they were perceived by its members.

Despite obstacles arising out of political tensions and antisemitism, 1912 paved the way for the emergence of a dynamic Greek Jewish culture in Salonika. The Italian attack of October 1940 brought young Jews fighting with their Christian fellows as brothers in arms against the invader. A trajectory with many conflicts but vivid nonetheless, wastragically cut short at the time of the German occupation, as the overwhelming majority (95%) of the Jews in the city were deported and exterminated in the Nazi camps. In the war’s aftermath, the old identities such as Zionists or Socialists took different meanings, became permeable one to the other, interchangeable. They were affected by the traumatic common experience, by the State’s policies, by economic needs. Immigration to Israel, for example, was by no means the choice of the Zionists alone. To my opinion, and contrary to K. E. Fleming’s argument, the Holocaust did not complete the formation of a Greek Jewish identity; on the contrary, it made it even more complex. After all, the Germans and their collaborators persecuted Greek Jews for being Jews. More than ever, I think, today one can be “a good Jew and a loyal Greek”. However, only the second part of the phrase has a clear, literal meaning. Considering myself Jewish, I see many ways of being a “good Jew”.

Last year, the mayor of Thessaloniki, Yannis Boutaris, gave a widely acclaimed speech on the occasion National Holocaust Remembrance Day and the inauguration of the project for a Holocaust Memorial Museum in Thessaloniki. The mayor talked about the importance of remembering and honoring Thessaloniki’s Jews and the Museum as a symbol of “shame for what happened, for what we did, and especially for what we couldn’t or didn’t want to do”. Would you like to comment?

I cannot but recognize the mayor’s courageous role in making the Shoah an issue of public concern in the city. However, as a historian I feel quite unease with the rhetoric of his speech. We often overlook the fact that silence, forgetfulness or concealment are always linked to people and causes; in other words, concrete people forget, omit or conceal for very specific reasons, under specific circumstances. There are variations of silence. I already mentioned the censorship on the history of the genocide imposed by the right-wing victors of the Civil War, the unpunished collaborators of the Nazis who were quickly incorporated into the state machinery.

On the other hand, as we know today, those who survived the Holocaust had not forgotten anything; they had not stopped talking about itand commemorating it inside the Jewish world. It is just as likely that the witnesses of those times remembered as well the Jewish drama, with either indifference or compassion. There were also all those who had economic, political and social interests to keep quiet. The “shame” and the blame should fall on those who deserve it. In other words, in a city like Salonika, the generation of those that witnessed the deportation, knew facts, people and names.

Today Salonika is inhabited by new generations and newcomers. It is therefore time to think historically, to put an end to dominant and complacent narratives of any kind: narratives that ignore the indifference or the betrayal of collaborators, but also, the more recent moralistic rhetoric emphasizing a general “shame” which implies that all were guilty in the same way (all ultimately equals to nobody), while omitting the fact that some were really guilty, for complex reasons (which combine antisemitism and personal interests) perhaps, but in very precise and concrete way. The same goes for the state institutions. Andrew Apostolou‘s deep historical research on Collaboration goes in this direction, i.e. against simplifying narratives.

I feel equally unease regarding the ambitious project of the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Thessaloniki and I certainly don’t agree with the mayor’s rhetoric statement which decontextualizes (in an almost sacrilegious way) Primo Levi’s saying on Auschwitz: “here there is no why”. Because, on this specific issue, there must be answers to many questions: Why (another) Museum? Why not another Institution, or the reinforcement of the existing ones? Why so little is known on the planning, on the content, on who and how is taking care of all that? Why the Museum’s Institute should be based in Brussels? I think I am not alone in posing these questions.

In conclusion, what can the study of Greek Jewry and the Holocaust tell us for contemporary Greek society and the various political issues it is faced with?

Free from moralizing conformism, the study of Greek Jewry and the Holocaust may positively complexify history writing and nourish a more self-consciously critical stance towards phenomena such as antisemitism, the rise of the extreme right and revisionist trends in politics. In other words, Greek Jewish history may serve as a “referential framework” for developping historical sensibility and a critical mind.

A critical stance coming from historical sensibility, i.e. the ability to recognize and interpret phenomena from the past may help us on decide how to react on various issues. For instance, to resist the racist and antisemitic discourse that spreads through many channels and in various areas of social life, disseminating poisonous prejudices. In Greece these prejudices often pertain to ideas on order and security, which justify exclusion and violence -against refugees for example. There are also conceptions of society imagined in terms of health and illness, conceptions that are discriminatory and destructive. There are stereotypes of Jews pulling the strings behind the bankers or/and behind the Left, working together for the destruction of the Greek nation. In all these fantasies, in all these discourses -coming sometimes from official lips- we recognize the language of fascism and antisemitism. This is extremely dangerous; Golden Dawn is just the top of the iceberg.

For about forty years after World War Two, no respectable scholar or public figure would have thought to attempt a rehabilitation of fascism and antisemitism. Today, the normalization of revisionist discourse is shocking: for example, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s national conservatism claims to reconnect Hungary with the so-called ‘natural course of events’ and to stigmatize the Left as supporters of a hated history; the ultra-nationalist Polish right is engaged in a policy which aims to conceal the antisemitic dark past of Poland. No doubt, critical alert against historical and political revisionism is much needed today.

Interview by: Ioulia Livaditi and Nikolas Nenedakis