The Balkan region has long been associated with violent conflict, ethnic unrest and the fragmentation of states. Political scientist Vassilis Maragos’ recently published the book «Only of this boast I: that I loved the fatherland». Romantic patriotism and transformations of the fatherland in the case of Grigor Pûrlichev(1830-1893), (Herodotos publications, Athens 2018), sheds light on a historical figure representative of his time, the mid-19th century, which saw the birth and consolidation of nationalist ideals in the Balkans.

Grigor Pûrlichev, also known by his Greek name, Grigorios Stavridhis, was a poet born in the city of Ohrid (part of present-day North Macedonia). He had a Greek education but later espoused pan-Slavic ideals and played a part in the forging of ethnic identity for Slavs and Bulgarians. This switch in languages and identities is illustrative of the volatile nature of ethnic and national consciousness at the time, hence Maragos’ interest in his life and thought.

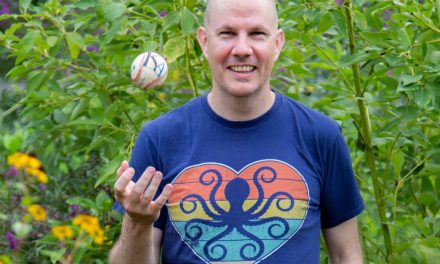

Vassilis Maragos has studied law, international politics and holds a PhD in political science. He has been living in Brussels since 2005, working for the European Commission. He has published a study on the formation of modern Bulgarian identity (Paisii Hilendarski and Sofroni Vrachanski. From Orthodox Ideology to the formation of the Bulgarian identity, in Greek, Athens 2009), a book of poems (Το προσωπείο του χρόνου / The mask of time, Athens 2010), essays on historical and national identity issues and he has translated poetry from Bulgarian and Polish.

Maragos spoke to Greek News Agenda* on the remarkable case of Pûrlichev, the nascence of nationalism in 19th-century Balkans, the fluidity of identities in the region and the way we can benefit from studying these issues today with an open mind.

Who was Grigorios Stavridhis or Grigor Pûrlichev? Why a book about him?

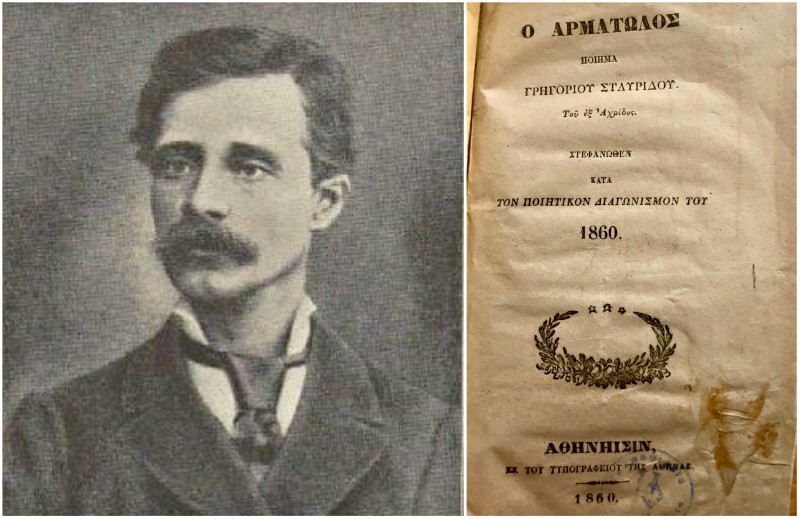

Grigorios Stavridhis or Pûrlichev was a poet in the Balkans in the 19th-century. He wrote poetry mainly in Greek. In 1860, while a student at the Athens University Medical School, he won the first prize at the National Poetry Contest held annually by the University, with his patriotic poem O Armatolos (The Armatole, a Greek mercenary under Ottoman rule). This contest was an institution of major cultural and national significance for Greece at the time. His victory stirred quite a debate in the Press (he was even described as a “modern Homer”!), as did his feud with Professor of Botany and senior prominent poet Theodore Orphanidis, who accused Pûrlichev of being a Bulgarian and an instrument of anti-Greek propaganda having used fraudulent means to win the award. It is quite telling that the Press almost unanimously rose in defense of the “young and virtuous Stavridhis “, given that Bulgarians were considered to be “dear brothers” of the Greek people, who had shed their blood for Greece’s freedom in 1821!

Left: Grigor Pûrlichev, Right: Title page of The Armatole

Left: Grigor Pûrlichev, Right: Title page of The Armatole

The fame and popularity brought to him by obtaining the laurel at the contest, however, was not enough for the young poet from Ohrid to make a caerer in Greek letters. At the next National Poetic Contest, which took place in 1862 – sponsored by the Odessa Greek merchant Ioannis Voutsinas – Stavridhis submitted a more ambitious poem, Skenderbeis (which was Skanderbeg, a Christian Albanian leader who rebelled against the Ottomans) but he did not manage to win the award. He thus returned to his hometown of Ohrid, and around the mid-1860’s he embraced Bulgarian nationalism and put himself at the forefront of the movement for the ecclesiastical and educational autonomy of the Bulgarians.

His ambition to pursue a literary career, writing in Bulgarian, led him to the Principality of Bulgaria, which was founded in 1878, but despite his efforts he never fully mastered the use of literary Bulgarian. Under the influence of pan-Slavic theories of the time, it appears he even tried to invent a pan-Slavic idiom (based on the Bulgarian vernacular) – perhaps inspired by Homer’s Greek as well as the Katharevusa Greek which he’d mastered – but after a poorly received attempt to translate Homer’s Iliad in this idiom (which he called Bulgarian), he abandoned his plans and returned to Ottoman Macedonia where he continued to work as a teacher in Bulgarian schools. He also left behind an interesting Autobiography in prose, written in Bulgarian, published posthumously.

Whilst not the only example of fluid ethnic consciousness at that time, Pûrlichev was an extraordinary case: originally a member of the Eastern Orthodox community (Rūm millet – Roman or Romaic nation), whose ideology he articulated in his poems, he initially – and perhaps somewhat hesitantly – moved towards a Modern Greek identity, which he probably perceived as compatible with the Bulgarian element of his genealogy and his Slavic local idiom) before moving on to a Bulgarian Slavic identity. This concept of a fluid homeland that we find in Pûrlichev, along with its romantic patriotism, is of immense importance for the understanding of Balkan nationalisms.

Besides, there has not been enough research into the relationship between the weak but culturally and ideologically ambitious Greek state of the mid-19th century with its “irredenta”, i.e. the variety of “unredeemed” populations of the Balkan hinterland, who had a complex relationship with Greek culture that had still an important influence in the region. Moreover, the 1860s turned out to be a milestone for the separation of the Christian population into the modern national communities of Greeks and Bulgarians. April 1860 marks the first attempt by the Bulgarian clergy in Constantinople to challenge the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and throughout the decade there were movements in several towns of the Balkan hinterland with a Slavic population defying the Greek metropolitan bishops appointed by the Patriarchate.

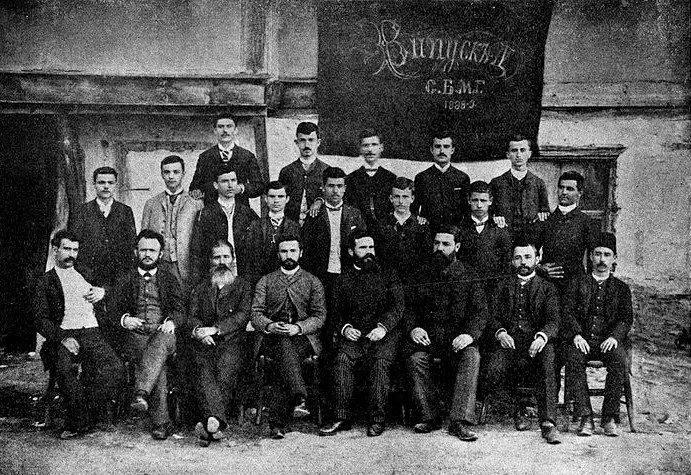

Pûrlichev (third from the left) among other teachers and students of the Bulgarian highschool in Thessaloniki (Wikimedia commons)

Pûrlichev (third from the left) among other teachers and students of the Bulgarian highschool in Thessaloniki (Wikimedia commons)

In short, this is a personality whose paradigm (and when compared with other figures who, despite their different native languages, did not renounce their Greek culture and identity) takes us back to the question of relations of Hellenic culture and ideology, in the course of the 19th-century with the diverse anthropogeography of the Balkan hinterland, highlighting ties and conflicts but also challenges which, to some extent, still affect us today.

It is also worth noting that Pûrlichev is among those figures which Bulgaria and North Macedonia have recently agreed to honour jointly in the context of good neighborly relations, as part of a recently ratified friendship treaty.

You discuss the national phenomenon in the 19th-century Balkans. At the end of that century, do subject peoples of the collapsing Ottoman Empire put their traditional religious identity first, or do they espouse the supremacy of a national identity?

By the end of the 19th century, this shift was largely completed especially in urban areas, yet the religious identity remained strong and continued to shape the increasingly national consciousness of the various groups. Despite their differences, the emerging new ethnic communities are based on the common framework of their preexisting religious identity. All Christian nations of the Balkans have some common features, since they come from a common melting pot, the Orthodox community. In fact, the severity of ethnic conflicts in the Balkans among Orthodox Christians who were previously united as the great Christian nation of Romaioi or Greeks in the pre-national meaning (the Rūm millet), with its predominantly Greek culture, is akin to a civil war. The partaking of all Orthodox Christians in this wider community is clearly asserted in various writings of the time presenting either the perspective of the Enlightenment, as in Rigas Velestinlis’ works (especially the New Political Constitution), or a defensive stance against modern nationalist ideology, as is the case with Historical and critical defense of the clergy of the Eastern Church, published in Pisa in 1815.

Can you elaborate on the subject of fluid national consciousness in the Balkans, allowing for easy moving from one to another, different identity? From what point in time onwards do national identities consolidate?

This fluidity is characteristic of Pûrlichev’s generation, especially for the region of Macedonia where we encounter many such examples. Comparisons with some of his fellow Ohrid townsmen – such as jurist Michael Potlis, who served as Minister of Justice under King Otto, and philologist Margaritis Dimitsas, who both chose to remain in Greece and embrace Greek culture – underlines the fluidity of individual and collective consciousness at the time. In fact, Ohrid’s “Bulgarisation” (a term used by acclaimed Bulgarian historians to define the process of imposing the use of the Bulgarian language in the city which had played such an important role in Medieval Bulgarian history) was initially challenged by a part of the city’s urban population, who wished to maintain their contacts with the Greek merchants of Thessaloniki and of Durrës in Albania. It was a time when the term “merchant” was often perceived to have an “ethnic” character as most merchants were considered to be Greek.

However, after a period of fluidity, national identities crystallized through the creation of state structures and the existence of national institutions meant to consolidate national identity (e.g. schools, national churches and so on).

Thessaloniki Bulgarians (late 19th century) by Paul Zepdji (Wikimedia commons)

Thessaloniki Bulgarians (late 19th century) by Paul Zepdji (Wikimedia commons)

At this point I would like to emphasise the relationship of the Bulgarians in particular with Greek culture. Until the mid-19th century, many Bulgarian scholars had received a Greek education and had often been taught the concept of the nation in Greek schools, which they later tried to apply to their own nation. Moreover, those who did not renounce Greek culture were assimilated into the Greek “imagined community”. They were the ones dubbed “Grecomans” regardless of whether their family or local environment was originally Bulgarian or Slavic-speaking, Albanian or Arvanitic-speaking or even Aromanian-speaking. Stavridhis, however, although having been accused as a “Grecoman”, later turned against Greek culture, which he sought to besmirch in various writings he intended either for publication or for teaching. It is in fact interesting that – apparently influenced by the ideas on the continuity of Greek civilisation since the antiquity – he tried to invent a rival Bulgarian tradition originating in antiquite times, centred around historical phenomena of the northern region of Greece and Thrace (Alexander the Macedonian , Orpheus, the Pierian Muses, etc.).

When and why do Slavic-speaking populations diverge from Bulgarian and Serbian nationalism and claim a distinct national identity? Do you consider the ethnicisation process of Slavic-speaking Macedonians to be successful?

This issue is very delicate and of crucial importance for comparative Balkan history, but it is not addressed in my study which focuses on the previous period, when the key issue was the connection between Greek culture and the ethnic emancipation of populations turning to their Slavic vernacular in search of a distinct identity centred on the general concept of a Bulgarian historical nation. It is quite revealing that Pûrlichev wrote initially his speeches (which were intended for rallies) in the local Slavic vernacular of Ohrid, which he calls “Bulgarian”, actually using the Greek alphabet. My research highlights Pûrlichev’s difficulty in embracing Bulgarian identity, since he was not happy with the way this identity was handled in the newly-founded Bulgarian state. I believe that, though he remained loyal to this identity, he never fully identified with Bulgarian ideology the way it was shaped by a new generation of scholars and politicians in Bulgaria, in the later period of his life.

To address your question, I think that this ethnicisation is the result of historical and political developments in the region, especially in the early 20th century. There is of course a prehistory of distinct cultural or territorial elements on which this effort is being founded. In this context, I think we ought to study, through a new unbiased perspective, the various processes of ethnogenesis so that we can better comprehend – beyond clichés – the identity of our neighbours, with whom we coexist and cooperate in order to meet the challenges facing today’s world. This is an issue of substance that can contribute to the modernsation of our Balkan mentality and to the stability of our region, which is a prerequisite for our prosperity and security. I also believe that future cooperation can be inspired from older forms of cultural and social coexistence.

Pûrlichev’s bust at his house in Ohrid (Wikimedia commons)

Pûrlichev’s bust at his house in Ohrid (Wikimedia commons)

In your opinion, does the agreement on the name of North Macedonia appease or aggravate aggressive nationalistic views today?

The comprehensive and comparative evaluation of the history of nations and national movements in the Balkans shows that these are communicating vessels. Various national movements (in their pursuit of self-determination) have at times tried to appropriate elements of their neighbours’ heritage (and Greeks, having the oldest civilisation in the region, have been subject to such appropriation). We have very close bonds with all our neighbours due to our previous coexistence within the community of the Orthodox or Romaioi, but also because of Byzantium, Christian Orthodox culture and the influence of Greek language in the region since antiquity. What is needed today in the Balkans is developing a joint historical consciousness that transcends the limits of each distinct national history, placing the peoples of the region within the broader history of empires and other formations in this part of Europe. After all, every people benefits from a deeper understanding of its neighbours. We enrich ourselves spiritually and we benefit politically when we understand and compare our identity with the identities of others without arrogance and narrow-mindedness. And the generosity of Greek civilisation is undeniable. Let’s not forget the enormous contribution of the classical Greek culture (a quintessential part of our identity) to the formation of modern Europe.

My personal view is that the Prespes agreement represents an approach for the conciliatory resolution of historical disputes, which could and should prove to be mutually beneficial by future developments, in the context of a clearly positive perception of interdependence in the region, contributing to regional stability and cooperation, within the framework of European integration. Let us keep in mind that the unification of Europe is principally a peace project, based on compromises and amicable relations and cooperation between neighbouring peoples.

*Interview by Costas Mavroidis. Translation by Nefeli Mosaidi. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this interview are strictly personal.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Agreement on the name issue ends disputes between Greece and FYROM ; International leaders and press on the Prespes Agreement ratification by Greek Parliament; Rethinking Greece: Alexis Heraclides on foreign policy formation in Greece, the Macedonian Question and the need for a secure national identity; Othon Anastasakis: We must focus on the positive outcomes of the Prespes Agreement; Loukas Tsoukalis: The Prespes Agreement puts an end to a long and divisive dispute; Miroslav Grchev: the Prespes Agreement leaves the faux-patriots without fuel; “The name issue and the inescapable national road” by Prof. Nikos Marantzidis