Learning from documenta is an independent research project situated between anthropology and art and brings together researchers from several other fields of interest. The project critically engages with the presence, impact and aftermath of documenta 14 in Athens, with reference to other artistic, economic and sociopolitical developments in Greece and internationally. documenta 14 was an art exhibition held between April 8 and September 17, 2017 in various venues in Athens, Greece and Kassel, Germany. In its 60-year history, this was the first time that documenta, one of the world’s most prominent artistic events, took place in two locations simultaneously, and the first time that it involved the Greek capital, with the phrase “Learning from Athens” in its title.

The project is an initiative of TWIXTlab, with the support of the Department of Social Anthropology at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences and of the Athens School of Fine Arts. The team behind the project is coordinated by Elpida Rikou, Adjunct Lecturer at the Department of History and Theory of Art of the ASFA and founding member of TWIXTlab, and Eleana Yalouri, Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Anthropology at Panteion. Learning from documenta held various open events within the context of the Athens Arts Observatory, a platform for public debate on current issues of art, culture and politics, which culminated in a closing event on October 2017.

Greek News Agenda and Grèce Hebdo, our sister French-speaking publication, held an interview* with one of the two coordinators, Elpida Rikou, on the nature of this pioneer project; she shared her thoughts on the presence, impact and aftermath of documenta 14 in Athens and informed us on the team’s plans for the future. With studies in sociology, social psychology and visual arts, Rikou has been teaching Anthropology of Art at ASFA since 2007.

Greek News Agenda and Grèce Hebdo, our sister French-speaking publication, held an interview* with one of the two coordinators, Elpida Rikou, on the nature of this pioneer project; she shared her thoughts on the presence, impact and aftermath of documenta 14 in Athens and informed us on the team’s plans for the future. With studies in sociology, social psychology and visual arts, Rikou has been teaching Anthropology of Art at ASFA since 2007.

What is documenta 14’s legacy for Athens? What are the main conclusions drawn from the Learning from documenta project and in particular from its closing event (4-8.10.2017)?

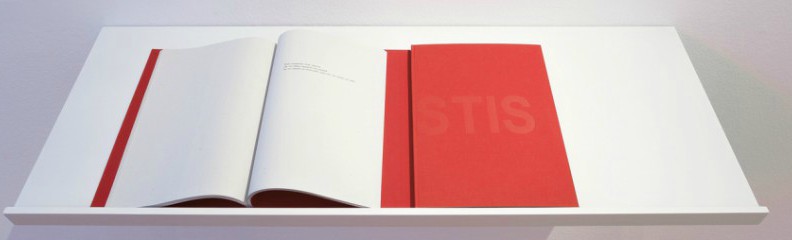

The significance of documenta is undisputable on an international level, and it is known for focusing on political issues, so of course its partial relocation to Athens is important for a number of reasons, such as, for instance, that it could help promote contemporary art in Greece. Regarding its legacy, I must say it is still early to reach any conclusion. Our project commenced two years prior to the exhibition and followed it through its various stages of development. The closing event marked the completion of our public events programme, and we are working towards a publication.

It is important to know that this is a collective project. Until the publication of our work, we can only comment on different aspects of this event, each from their own perspective. In my opinion, it is interesting this major event, which took place at such a critical time for Greece, created a field of tension that helped people, at least those already engaged in this type of pursuit, to define their own position in relation to the contesting sides emerging through these debates and controversies, and sometimes to express their views in public. And thus it helped shape the arts sphere in Greece in new ways, especially within an international context – regardless of whether this result was included in the original intentions of the organisers. On the other hand, it has perhaps disrupted some local initiatives that had started to develop prior to the event, and which are now in a restructuring process.

As far as larger audiences are concerned, I don’t think the event truly reached them, but maybe it wasn’t aiming at that to begin with. It did help contemporary art to be taken seriously, something that was not a given in Greek society. Apart though from this legitimisation, it didn’t do much to change the general public’s indifference or skepticism towards contemporary art. It has of course been noted that many young, aspiring artists, art historians, curators etc who engaged in the event gained valuable experience and yet,Greek artists were not given an important, decisive role.

It can be argued that Greeks were appointed mainly to operational posts or as intermediaries between the organisers and the local scene, with rather few instances of actually being involved in the curatorial process. I believe that Adam Szymczyk, the artistic director of documenta 14, was interested in Athens as a symbol for the South and the hardships it goes through, rather than a real, contemporary city. It also remains unclear whether the organisers’ collaboration with Greek institutions helped shift the state’s priorities regarding the promotion of contemporary art, as opposed to the traditional prioritisation of ancient culture. In short, documenta 14’s legacy for Athens is rather ambiguous.

What have been the main goals of the Athens Arts Observatory? Is it an ongoing project?

What have been the main goals of the Athens Arts Observatory? Is it an ongoing project?

As I said, the Learninig from documenta closing event signaled the completion of our public events programme, which aimed at openly discussing this subject. We continue our work with the intent of publishing a volume (hopefully a bilingual English and Greek edition) recording activities linked with documenta 14, but also including additional data. It might take one or two years before the publication is ready, which will give us time to process and evaluate our studies and observations.

I think that ours has been a worthwhile project, combining artistic and anthropological approaches and, compared to other initiatives of clearly more artistic nature, it caused a sort of uneasiness to documenta’s organisers. Of course Mr. Szymczyk participated in our first event, and other people involved in the documenta 14 took part in some of the events that followed, and we deeply thank all of them for that, but a comprehensive dialogue was never truly achieved. We did, however, manage to continue with our research and make the best of it.

We are not strictly focused on documenta 14, but instead use it as a starting point to study and evaluate international tendencies in the field of the arts and the way they influence local scenes, especially the Greek scene. At our closing event we tried to address all the possible important subjects in question, from art and politics to ethnic and gender issues. I can certainly not draw a specific conclusion from this event now, but what I can say is that I found very interesting how the panels of these open discussions consisted of people working in the artistic workshops during that same period.

As far as the Athens Arts Observatory is concerned, this initiative (one of several that emerged within this context) will continue as part of TWIXTlab, a long-term project of an artistic, educational but also political nature, bringing together anthropology, contemporary art and everyday life. We are based in Pangrati, Athens, where we hold various workshops and events and conduct research working in the same direction as we did in Learning from documenta.

In your research activities, you use methods and tools from anthropological studies in order to assess the relationship between society and arts. Would you like to elaborate on this?

In your research activities, you use methods and tools from anthropological studies in order to assess the relationship between society and arts. Would you like to elaborate on this?

As I said before, documenta 14 is basically an occasion for linking social sciences and contemporary art in order to observe the political and social results this could produce. I have a particular interest in this, especially since I began teaching at the Athens School of Fine Arts. Eleana Yalouri, the co-coordinator of Learning from documenta, is the head of the Anthropology Research Lab at Panteion University. Another member of our team -who also co-coordinated the closing event- is Apostolos Lampropoulos, Professor at the Department of Literature at the University Bordeaux-Montaigne, and there are many more members including anthropologists, art historians, artists and others, from Greece and abroad. The project gave us the opportunity to meet and collaborate with scholars conducting researches in these fields on an international level.

As was also evident in some projects within documenta 14, the existence of links between the social sciences, especially anthropology, and contemporary art is now widely accepted. This could also be traced in the discourse used by the organisers, although never in an explicit manner. This interaction is very fruitful, I believe, but it also produces conflicts, often creative but occasionally just jarring, i.e. when an artist uses a hand-held camera for impromptu filming, and anthropologists raise the issue of intrusion on privacy.

One of the most interesting contributions of this correlation is, I believe, that it offers tools for the consideration and study of society via an artistic project. Often art, especially in its more politicised form, seems to just “produce ideology”, in a rather superficial way, without really taking into account the actual impact this could have, or not have, in the actual society. This was one of the problems with some of the ideas expressed in documenta. Personally, I wish to contribute to an art making which is more situated.

Contemporary art: is it a matter exclusively linked to traditional Western metropolises or is there something changing with the emergence of new capitals such as Athens, or other non-European cities?

Contemporary art certainly has its roots in a Western, and particularly western European view of reality, and so also carries a colonial heritage. I believe that this is where its basis still stands, and since the 80’s there are constant efforts to handle this legacy, with documenta being one prominent example. The intentions of deconstructing these structures are surely honest, but the results are often questionable. New art capitals emerge often, following certain trends and fads. A few years back it was Istanbul, now it’s Athens; there is a constant quest for innovation and trailblazing. But this can end up in exploiting areas in crisis and also exoticising societies. By trying to better understand how art production functions in relevance to society, we hope to contribute to the discussion of these subjects.

Greek cultural identity was until recently strongly associated with antiquity. This approach was also evident in the Greek state’s cultural policies. Are there new trends emerging as far as Greek cultural identity is concerned? Can Athens be a cultural and artistic hub where international artistic movements meet with “Greek” art?

Greek cultural identity was until recently strongly associated with antiquity. This approach was also evident in the Greek state’s cultural policies. Are there new trends emerging as far as Greek cultural identity is concerned? Can Athens be a cultural and artistic hub where international artistic movements meet with “Greek” art?

The question of whether and how we can define a Greek cultural identity is very difficult. In any case, it doesn’t only have to do with culture, but also economy. If Greece today continues to depend symbolically as well as financially -through tourism, for instance- on Ancient Greece, could contemporary art provide a viable alternative? One of the things I realised during our research on documenta 14 is that we have been naïve to isolate art from economy – especially at this juncture, taking into account the country’s situation. Art is not disconnected from society.

Now, regarding the notion of national identity, any anthropologist, myself included, would deem problematic both the concept as well as the singular number of “identity”. Let’s say that many people feel they can relate to certain social constructions. documenta 14 was not very successful in challenging these links between Greek identity constructs and antiquity; it actually promoted a number of stereotypes, drawing parallels between contemporary and classical Athens. The so-called “crisis” has put Greece in the centre of international attention, either in a bad or good light, and this is sometimes used for marketing purposes. There are developments and initiatives in the field of contemporary art, but whether this will have any effect on society remains to be seen.

There is definitely an interaction with international movements and networks that did not exist a few decades ago. We used to be much more isolated. What I am not sure about is whether we can talk about “Greek” art. In the 80’s (as well as before, obviously) there were some examples of artists trying to combine contemporary influences and some form of “Greekness”. Today’s artists are rather trying to deconstruct this type of identity creation. I don’t think this is a time that encourages self awareness through a national identity. Certain artists are still interested in forming identities, but these have to do with different types of identity politics: gender identities, or being part, for example, of the LGBTQI community, etc.

Read more about the Learning from documenta project: Article at the international web journal ONCURATING; Audio: Athens Arts Observatory / Learning from documenta on Mixcloud

Read more on documenta 14 via Greek News Agenda: documenta 14: Learning From Athens; documenta 14 Starts Gradually Unveiling; (Un)learning from Athens: documenta 14 Inauguration; documenta: art in a southern state of mind

See also on Greek News Agenda:

Athens as a cultural spot: Nikos Souliotis on Athens’ modern cultural identity; Marina Abramović: Athens grows as a major cultural spot; Ares Kalandides on rebuilding the country’s reputation; Katerina Koskina on the need for cultural dialogue & EMST’s role as an arts capsule for the city branding of Athens

Arts in Greece: Denys Zacharopoulos: A museum should function as an open window between the private and the public life of people; Alexandros Psychoulis on the idea of symbiotic bliss & the reality of working as a visual artist in Greece; Gary Carrion-Murayari on “The Equilibrists” & the contemporary arts scene in Greece; Efi Kyprianidou on Art and Compassion; Athens School of Fine Arts celebrates 180 years

*Interview and translation by Nikolas Nenedakis, Magdalini Varoucha and Nefeli Mosaidi