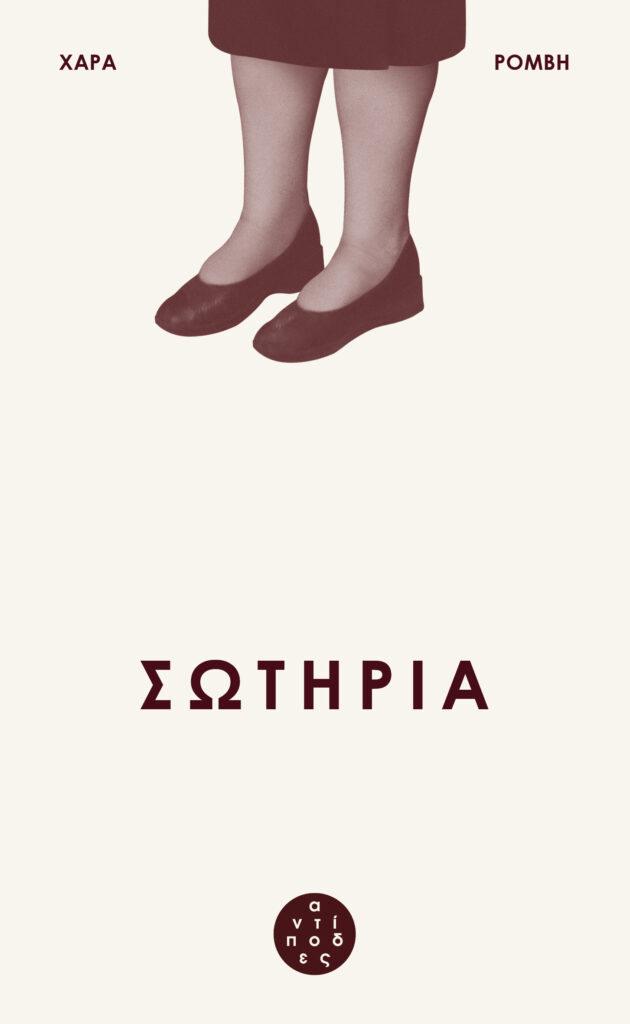

Chara Romvi was born in 1985 in Athens. The short story collection Sotiria [Antipodes, 2023] is her first book.

Your first writing venture Σωτηρία [Sotiria] (Αntipodes, 2023) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

Sotiria is a collection of six short stories, the stories of six heroes taking place in the 1980s and the 1990s. I didn’t initially intend to make a collection; my intention was to write a story that I had in my mind for quite some time, the story of Sotiria, which is the second story of the book. Actually, Sotiria was my first attempt to write in prose, my start in writing. Upon finishing this first story, a new concept opened up in my mind, which whetted my appetite to write more. The rest followed. It was a process which took around four years. However, when I started writing, I didn’t imagine that I could someday have a finished work that would be published. The beginning was a sort of experiment, I just wanted to challenge myself I could make it.

“I think that all six heroes, in one way or another, are concerned with salvation as a concept, whether they are saved or not saved”. Tell us more.

The heroes of the book are faced with an event, part of it tragic, part of it fatal, part of it like a prank, and part of it just awkward. However, in all six stories the concept of salvation plays a role, at times decisive and at others latent. I think that usually salvation as a concept is mainly associated with difficult situations, especially with life-threatening situations. Nevertheless, I think it’s a concept that applies to us whenever we feel stuck or trapped in a problem. Therefore, I would say that in a way we spend our lives trying to save ourselves from something, big or small. Given this thought, the title of the book [‘sotiria’ means ‘salvation’ in Greek] was an easy case for me. So deep and wide is this concept that I could imagine it as the title of most books I have read.

The book takes place in the 1980s and 1990s, a period of affluence, followed by the years of the financial crisis. What made you turn to this period? Was the past a way to talk about the present as well? Is tenderness a way to talk about a, sometimes, repressed collective past?

The financial crisis we experienced in the last years made us all, more or less, turn to our collective past, focusing on the decades of the 80s and 90s. Undoubtedly, it was an era where profound changes occurred. Most people lay emphasis on the affluence characterizing that period, which is why we see strong nostalgia manifested in many ways. At the same time, there is a widespread belief that this period was phoney and essentially was the root of all evil, that is the financial crisis. This contradictory discourse regarding this era interests me a lot, I would say fascinates me. I set my stories in the 80s and 90s to examine these contradictions and try to understand how this era addresses the present.

How does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Where do the personal, individual micro-stories meet the collective History of the world?

I believe that literature provides the deepest understanding of society and the human condition. And that’s because the reader is emotionally involved. Of course, we can understand society through other disciplines, such as History and other social sciences, but never in so comprehensive a way, as is the case with literature. The main goal of a book is to move the reader through the stories of the heroes and not to simply provide the reader with information. Well, knowledge coupled with feeling is the most essential knowledge. Literature, unlike History, talks about the world through personal stories. Usually made up, but that’s the amazing thing about literature; it manages to create reality through fiction.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is writing itself. I cannot think how one can write literature without grappling with language in all possible ways. In literature there are no compelling stories but compelling narratives. No story is witty or original unless it is written with style. Even the most common story, if told in literary language, can be unique. One thing that I have observed lately is that the concept of “spoiler” has become a common thing when talking about books. Obviously, this is directly linked to the habit of watching TV series. But I don’t think spoilering has a place in literature. In literature that notion of delight and surprise lies in words. That is, in language.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. Would you agree that earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

The vast majority of writers in our country cannot make a living through writing. Writing is a very tough and demanding job needing time, and in fact quality time. Writing is not a leisure activity. On the contrary, writers in Greece write by sacrificing their free time. This definitely makes their life far more difficult. Unfortunately, in Greece the book is not a cultural product bringing profit, neither for writers nor for publishers. If the percentage of readers were not that low, things would be much better. Things would definitely improve if there were a provision from the state – a comprehensive policy for the book. Indicatively, grants to new writers and financial prizes would be beneficial.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE