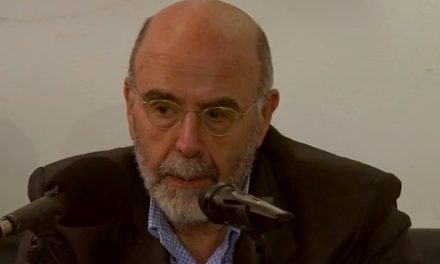

Louis A. Ruprecht Jr. is the inaugural holder of the William M. Suttles Chair of Religious Studies in the Department of Anthropology, as well as the Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia (USA). Professor Ruprecht’s latest book is Reach Without Grasping: Anne Carson’s Classical Desires (Rowman and Littlefield, 2022). He is currently working on a new book project tentatively entitled The Renaissance Sappho: Fulvio Orsini’s Songs of Nine Illustrious Women (1568). For his work bringing ancient ideas to modern-day scholars through the Georgia State University Center for Hellenic Studies, Dr. Ruprecht has been granted Greece’s order of merit, the Gold Cross of the Order of the Phoenix.

Professor Ruprecht spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the concept of “cosmopolitan Hellenism” utilized in the Center for Hellenic Studies at Georgia State University as a way to re-imagine the Greek experience as an essential piece of world heritage, belonging equally to everyone; on the transformative moral value of Greek tragedy and its political consequences in modern democracies; on how religious concerns with “pagan art” were transcended by belief in the the virtues of classical art; on Sappho’s understanding of the tragic and transformative dimension of eros; and finally, on the future of Classics departments in U.S. Universities. As professor Ruprecht notes, “most successful Classics programs seem to me to have moved beyond strictly philological and strictly classicizing approaches to the ancient world, and to have harnessed the resources of anthropology, among other disciplines, to enable ancient materials to speak to more contemporary concerns. Particularly noteworthy has been the application of the categories of identity to the ancient world: race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, and class.”

You have been the director of the Center for Hellenic Studies at Georgia State University since 2012. What is the place of Hellenic Studies in a modern University? How can ancient Greek culture and history illuminate contemporary concerns?

The term “Hellenic” is ambiguous, but this ambiguity can be both fruitful and productive. The term is far less familiar to the North American public than “Greek,” and thus it tends to need some explanation. My own view is that the term properly encompasses everything from the earliest Bronze Age Mediterranean materials, the marvels of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, the uncanny encyclopedic celebration of Greek culture and language in the Roman period, the crowning Byzantine achievements, and so on, up to and including the modern poetic contributions of Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933), George Seferis (1900-1971) and Odysseas Elytis (1911-1996), not to mention stunning contemporary Greek achievements in cinema, music and theater. It is a rich and expansive legacy, indeed.

From an institutional perspective, this legacy has tended to be divided between Classics and/or Classical Studies departments, which cover the antiquities, and Modern Greek Studies departments, which cover mostly the previous two centuries. The Byzantine material has tended to be short-changed by such institutional arrangements.

There is a curiously religious reason for some of this, I believe. If we look at the way religious history is taught at most Protestant seminaries in the US, then we will see that there is great attention paid to origins: to the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, to early church history, and to the history of early social and institutional formation. But then we leapfrog ahead to Luther, Calvin and the moderns. The Middle Ages tend to be short-changed since, from a Protestant perspective, this period is largely seen as the history of a series of excesses and errors. You see that prejudice alive and well in Edward Gibbons’s comments about the Byzantine Empire.

When I was appointed as Director of the Center for Hellenic Studies at Georgia State University, I was concerned to work against this sort of compartmentalization. I wanted to integrate Archaeology, Classics, Film, History, Literature, Music and Theater more seamlessly in an ambitious series of public programs. I also wanted to consider Greek materials in the broadest possible terms: Bronze Age, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, Byzantine, and Modern. Of late, we have even pushed the historical frame back into the Mesolothic and Paleolithic periods, since there have been so many exciting pre-Neolithic archaeological discoveries in Greece, both on the mainland and in the islands, over the past twenty years.

In order to celebrate this range and to express our expansive Hellenic commitments, I established “cosmopolitan Hellenism” as the Center’s thematic centerpiece. The idea is a product of the vast expansion of Hellenistic culture in the wake of Alexander’s conquests. A simplified form of koine Greek became the language of diplomacy and commerce. Greek culture became a sort of “umbrella culture,” one that held an ethnically and culturally diverse empire together.

The great philosophical schools that emerged after Aristotle (who had been Alexander’s tutor)-especially the Epicureans, Skeptics and Stoics–all emerged as attempts to think philosophically in terms broader than the more narrowly Greek perspective of Aristotle permitted. Egypt, Mesopotamia and India were not only important points on the Hellenistic map now; they were philosophically significant in novel and creative ways.

Diogenes of Sinope, who died in the same year as Alexander (323 BCE), was famously complimented by Alexander for his fierce independence, autonomy, and seemingly devil-may-care moral attitudes. Diogenes also famously coined the term kosmopolitês, or “citizen of the world.” He did so in response to the question of where he was from (he was from Sinope in Asia Minor). His answer–“my city (polis) is the world (kosmos)”–was intended to escape the power and prominence of the question of where we come from. Where we are from, he suggested, was less definitive, less philosophically interesting, than where we wish to go. Our world is supposed to grow larger and more philosophically expansive. Where we begin does not limit or determine where we may end up.

It is illuminating to imagine this as the statement of a Greek philosopher from Asia Minor. In short, Greeks had always traveled; their self-identification with a seafaring culture had something to do with that. The Greek colonization of the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts created a network of port cities throughout the Mediterranean that enabled such travel and even celebrated it. The Greek diaspora is one with a very long and very rich history indeed; cosmopolitanism is one of its chief virtues.

Today, the Greek diaspora is impressively global, of course. Toronto and Melbourne are enormous, and enormously significant Greek cities. Even Atlanta is home to tens of thousands of Greeks who have called the city home for more than one hundred years. It hosts an important and energetic Greek Consulate. It is an Orthodox Greek Metropolis with more than 70 parishes. It is, in all of these ways, a thrilling illustration of Greek internationalism and its cosmopolitan commitments.

In an historical moment when US universities have intensified their commitments to internationalism, and have opened their doors to permit a far larger percentage of their student bodies to come from abroad, then the moral commitments embodied in Hellenism, both historically and philosophically, seem uniquely well suited to the moment.

Here in Atlanta we have utilized the concept of cosmopolitan Hellenism as a way to re-imagine the Greek experience–Hellenism in the fullest sense–as an essential piece of World Heritage, belonging equally to everyone. It is here, I believe, that we find the most productive “elective affinity” between Hellenism and the modern research university.

What does “Hellenism,” “Greek thought” or what you have termed “the Greek phenomenon,” mean to you?

I provided some sense of my answer to this question in my previous response. In my own work, I have tried to sketch out the long historical arc of Hellenism, one that draws on Greek archaeology, to be sure, but that focuses more on how the tropes of Hellenism have been adapted and translated into later historical periods and other cultural environments.

In Was Greek Thought Religious? On the Use and Abuse of Hellenism from Rome to Romanticism (2002), I attempted to show how the very terms, ‘Hellenism’ and ‘Hellene’, had shifted in their Greek meanings, and been subject to varying translations in Latin and later Romance languages. Religious changes had a great deal to do with these shifts in meaning. One of the things that Hellênes and Hellênismos were later taken to mean were “pagans” and “paganism,” respectively. The shift from “paganism” to Christianity thus represents a seismic cultural shift in the history of the Mediterranean basin.

Yet what is most striking to me is how, while viewed one way, the transition from traditional Greek religion to Christianity changed everything, viewed another way, it changed very little. Christianized Greeks in the Roman Empire continued to dress, to eat, to engage in philanthropy, and to marry much as they had done before. A distinctively Christian culture that altered these traditional life-ways would not emerge until many centuries later.

What this suggests is that we will do well to attend to the simultaneous continuity and discontinuity in the long history of Hellenism. The continuities are highly suggestive to me. That is why much of my scholarly research has attended to the later iterations of Hellenic tropes in areas as diverse as art and artistic display in museums, democratic culture and democratic politics, erotic desire and moral psychology, as well as to theatrical concepts like tragedy and comedy, about which I will have more to say below.

I concluded Was Greek Thought Religious? with a chapter devoted to the revival of the Greek Olympics in 1896. The Modern Olympics seem to me to be the most dramatic and global example of a Neohellenic movement in world history. It is remarkable for this very reason that the history of the Olympic Revival has been so largely forgotten in little more than a century. Religion, as it turns out, is shot through Olympic history.

The ancient Olympics were established as a religious ritual event at the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia in (or around) 776 BCE. They were prohibited by the Christian emperor, Theodosius, for religious reasons in 393 CE. An essential part of the case for their revival in 1896 was also religious, as is clear in the speeches and writings of their “Renovateur,” Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937). In short, the Olympics were created, then cancelled, and then revived, all for religious reasons.

What those reasons were is a fundamentally historical question. As I noted above, Hellenism-viewed as a vast archive of cultural experience–also provided a spiritual foundation for modern internationalism and cosmopolitanism, alike. In the specific case of the Olympics, we may notice that sport trades in the currency of limitation: limits imposed by rules; limits imposed by lines and boundaries; limits imposed by our physical embodiment itself. It is the careful choreography of such limits that enables transcendence to come into view. We must have something to transcend, after all. This, I suggest, is one reason that athletics was an important cultural site as well as a source of reflection among philosophers and religious thinkers alike in antiquity, and why it continues to be so today.

© Topical Press Agency—Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In your speech accepting Greece’s order of merit, the Golden Cross of the Order of the Phoenix, you noted that “Greek tragedy was intended to be a raft of democratic hope.” Could you expand on that?

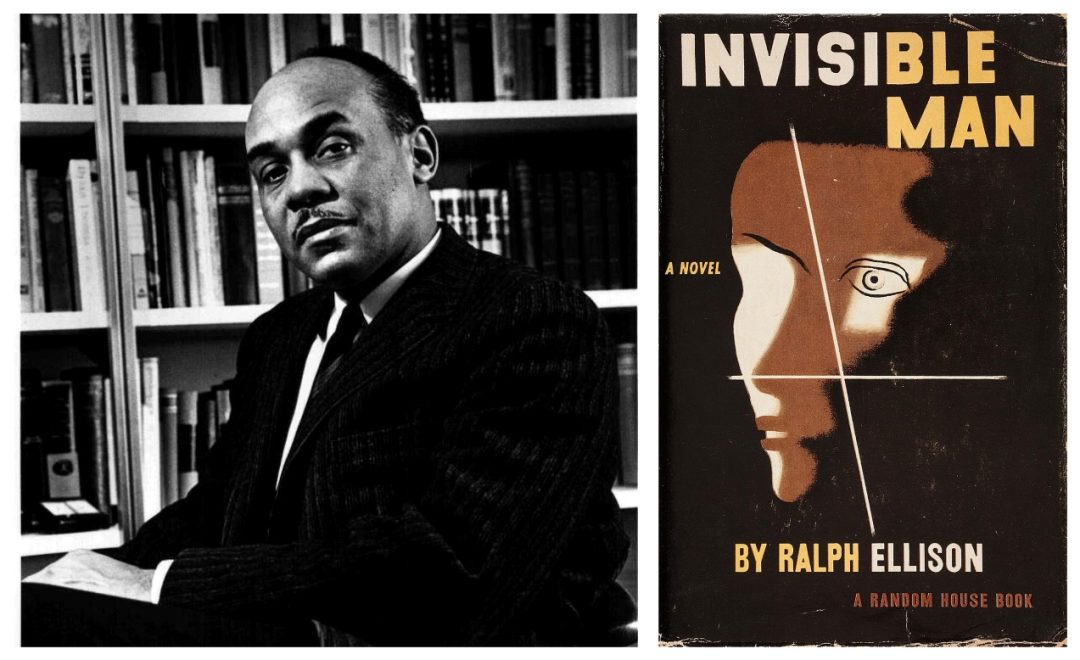

The phrase, “a raft of hope,” comes from Ralph Ellison (1914-1994), in the new Preface he composed for the 30th anniversary edition of his classic novel, Invisible Man. In addition to being the author of powerful fiction examining the dynamics of race and ethnicity in the United States, Ellison was arguably the finest democratic essayist the US produced after the Second World War. Here is the passage in question:

“So if the ideal of achieving a true political equality eludes us in reality–as it continues to do–there is still available that fictional vision of an ideal democracy in which the actual combines with the ideal and gives us representations of a state of things in which the highly placed and the lowly, the black and the white, the Northerner and the Southerner, the native born and the immigrant combine to tell us of transcendent truths and possibilities such as those discovered when Mark Twain set Huck and Jim afloat on the raft.

Which suggested to me that a novel could be fashioned as a raft of hope, perception and entertainment that might help keep us afloat as we tried to negotiate the snags and whirlpools that mark our nation’s vacillating course toward and away from the democratic ideal1.”

It seems to me that what Ellison saw as the role of the novel in modern democratic societies was fulfilled in the ancient Athenian democracy by their dramatic festivals. In the Poetics, Aristotle’s reflections on ancient Greek tragedy, he observed that tragedy is an imitation of an action that is:

“serious, complete, and has a certain magnitude. It takes the form of showing rather than telling. Through pity and fear [di’eleou kai phobou] it manages the katharsis of these emotions. (Poetics 1449b25).”

There has been a great deal of discussion of that term, katharsis, which was partly a medical term that suggested a purging, or cleansing, in the medical context. That cannot be the meaning here, since tragedy does not eliminate the emotions of pity and fear. We still pity Antigone at the end of her tragedy, and we still fear the awful fate that led Oedipus to disaster. I prefer to think of katharsis as “transformation” in relation to tragedy. The Greek audience that witnessed the plays of Sophocles and others left the Theater of Dionysus with their pity and fear transformed into something else, something we might best think of as “compassion.”

That is the transformative moral value of Greek tragedy, and it suggests that tragedy explores a very particular kind of pain and suffering. Tragedy explores the full range of possibilities of what free human beings may choose to do; there is often a great deal of pain created by their choices. But pain and suffering are tragedy’s first word, not the last. Tragedy is ultimately a hopeful genre, since tragedy puts forms of suffering on display, like Oedipus’s, that can be redemptive. Sophocles shows us that, after all of his ordeals, Oedipus became a god of sorts in the sacred grove at Colonus, and his spirit became an enduring blessing to the city of Athens. His suffering was transformed into redemption, and the horror that people first felt when confronted with Oedipus’s fateful curse was transformed into compassion and care.

The superb Broadway theater critic, Walter Kerr (1913-1996), published a ground-breaking study entitled Tragedy and Comedy in 1967. His argument sounds counter-intuitive until you think about it. Tragedy, he argues, is prior to comedy. Historically speaking, the tragic festivals in Athens were created more than one generation before the comic festivals. Kerr also insists that tragedy is philosophically prior. His reasons for saying so are complex. Comedies do not end well, and tragedies do not end badly. Tragedies, in fact, may end in all sorts of different ways; the ending is not the point of a tragedy. In reality, tragedies point beyond their endings to a new and more open future. They transcend the boundaries of the stage where they are performed. Comedy, by contrast, remains on stage and is rooted to the ground. Comedy is fundamentally cruel; it invites us to laugh at what terrifies us. Comedy offers no future; it simply grinds to a halt and the curtain closes. Without a future there can be no hope. “Tragedy is the genre than promises a happy ending,” Kerr concludes. “It is also the form that is realistic about the matter2.”

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the concept of tragedy in ancient Athens, in early Christianity, and in modern moral philosophy. I was fortunate to have been able to live in Athens for the two years that I was researching and writing. That work eventually became my first book, Tragic Posture and Tragic Vision: Against the Modern Failure of Nerve, published in 1994. I was especially struck by the way Athenian tragedy provided a model for the Synoptic gospels. There, too, we witness tremendous suffering in the depiction of Christ’s Passion, but the form of suffering placed on display, as awful as it is, was believed to point to redemption. That is the mystery of transformative katharsis, and it has both political and religious consequence. The early Jesus movement was a community grounded in compassion and reconciling love. Modern democracies are grounded in compassionate social practices designed to elevate the values of equality and fraternity, to unleash the full possibilities of all our citizens.

The ancient Athenians saw the political and religious purposes of tragedy very clearly. The city sponsored the festivals each year and attendance was considered a civic duty. I have long wondered what a modern democratic analogue to that spirit of marvelous dramatic occasion in the Theater of Dionysus beneath the Athenian Acropolis might be. Ralph Ellison, as well as Cornel West, see this spirit of tragedy alive and well in the musical tradition of the Blues. Blues music also grew out of the tradition of Gospel music. These musical notes are all tragic, which is why they are ultimately grounded in compassion and hope, and why they may lay claim to redemptive love as a transcendent value.

One of your basic fields of research is religion and you have written on the complicated relationship between religion and art. Can you tell us more about that?

An older theory of “secularization” in the 1950s and 1960s suggested that religion was destined to go away in the modern age. Somehow, it was thought that traditional religious belief could not withstand the challenges of the new sciences of Astrophysics, Cosmology and Evolution. The social scientists who believed this had a very hard time explaining the rise and renewal of political religion around the world in 1979-1980. This did not happen only in India, Iran and Israel; it happened at the Vatican and it happened in the US as well. My former professor and close personal friend, Bruce B. Lawrence, wrote the first comparative study of this phenomenon, Defenders of God: the Fundamentalist Revolt Against the Modern Age, in 1990. Another close personal friend, Jeffrey Stout, has written the finest study yet produced on the limitations of this version of secularism and secularization, in a book entitled Democracy and Tradition, in 2004.

Clearly, religion has not simply gone away.

My own view of the modern era is that it represents a revolutionary period in which religion goes elsewhere, not away. Religious impulses and spiritual energies are never strictly contained within churches, synagogues, mosques, temples or what have you. I am especially struck by the ways in which traditionally religious energies have been placed in the service of art–both for artists who produce their works and for the viewers who make pilgrimage to see them. In a word, public art museums are one of the exceptional and novel places where religion has gone in the modern period.

Few contemporary visitors to public art museums today consider the religious curiosity of the collections at their inception. From the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum, to the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre, the Apollo Belvedere and Laocoön Group in the Vatican Museums, and the Aeginetan Sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia now housed at the Glyptothek in Munich, Classical statuary constituted the heart (if not actually the soul) of most public art museums in the first several generations of what I consider to be the “museum era” (1767-1830).

In my book, Winckelmann and the Vatican’s First Profane Museum (2011) , as well as in subsequent articles published in 2018 and 2022, I have presented the archival evidence from the Vatican Library and the Vatican Library’s Secret Archives which confirms that Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), better known as a Neoclassical evangelist and Art Historian, was also the semi-secret curator of the Vatican’s first “Profane Museum.” I was delighted that last special exhibition the Vatican Museums curated before the COVID lockdown focused on this story. “Winckelmann: Masterpieces Throughout the Vatican Museum” was on public display from November 9, 2018 through March 9, 2019.

Founded in 1767, expanded and completed in 1792, looted by French Revolutionary forces under Napoleon in 1796, and then later repatriated back to the Vatican in 1818, Winckelmann’s small museum first “curated the profane,” which in turn enabled the cultural and art-historical domestication of what until then had mainly been seen as “pagan idols.” I think that it is important for us to remember that these statues had not changed, in most cases, for several thousand years, except in those rare cases when they were restored. Rather, our ways of seeing these statues, the manner of our looking, has changed dramatically.

And so it was that these statues of Greek gods, goddesses and heroes, most of them rendered in the nude, were legitimated and domesticated in the symbolic capital of the Christian world (Rome). This happened in stages, but stages that were cumulative and that developed with surprising rapidity. These “pagan idols” would first be seen as “fine art,” then as exemplars of “ideal beauty,” then still later as “national treasure.” After Waterloo, all of the previous religious concerns about the Vatican’s Museo Profano had disappeared; the cardinals and the Pope simply wanted their national treasures back.

What Hans Belting has called the Era of Art, which was also the beginning of what I am calling the Museum Era, thus offers a surprising case study of the casual flirtation with pagan form that would have a very long subsequent cultural reach and influence, both in the Mediterranean world and beyond it. Religious concerns with pagan art were transcended by belief in the spiritual power of ideal beauty and the transcendent virtues of Classical Art.

Your work focuses on how Greek cultural forms have been adapted in later historical periods, and the subject of your seminar at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens next year will be Eros. How has the concept of Eros morphed since ancient times?

For many years I have taught a course entitled “Religion and Sexuality”; I think “Eros in Antiquity” might be a better name for the course, since the mystery with which I begin involves the question of how best to translate the Greek word, eros. It is striking, though unfortunate, that the term ‘erotic’ in modern English has a more narrowly sexual connotation. By contrast, the ancient Greek terms, erôs and ta erôtika, implied something like passionate and overwhelming desire, a desire that has the power to undo completely the person who experiences it.

Ta aphrodisia referred to a person’s sexual experiences in ancient Greek; ta erôtika referred to something else, something far more mysterious, and even sacred.

Sappho of Lesbos (who was poetically active sometime around 600 BCE) was famous, among other things, for her uncanny ability to coin new terms. She was the first to call eros “bittersweet” (literally, her term was “sweet-bitter,” glykypikron, in Aeolic Greek). In that poetic fragment (#130), Sappho also refers to eros as a “limb-loosener” (lusimelês).

The term is a rhetorical echo of the Homeric idiom for death, where a warrior who is struck by a javelin or a sword is said to have their limbs “unstrung.” The body collapses, no longer in control of itself, and the soul escapes groaning through the portal of the dying person’s mouth. Sappho takes this image off of the battlefield and places it dramatically within the human heart. Eros is not in our control; eros often seems to control us.

Sappho, like other Archaic Greek lyric poets, analogizes such an erotic experience to death. In her equally famous Love Triangle Fragment (#31), she says explicitly that the sight of her beloved speaking to someone else drives her nearly mad with physical symptoms, such that she seems nearly dead in her own mind. As Anne Carson puts this point, “change of self is loss of self to these poets3.”

Sappho’s genius, like Socrates’s, was to see change of self also as a form of soulful transformation. The power of eros lies in its capacity to transform us. This is a transformation that is painful, no matter how blessed it may also seem. Sappho’s term, ‘sweet-bitter’, captures this tragic and transformative dimension of ta erôtika quite well. The idea culminates in Socrates’s astonishing claim in the Phaedrus (244a-245c), that eros is indeed a madness, but that some forms of madness are actually gifts from the gods. Passionate desire is precisely such a gift, one that expands our moral and emotional horizons, generating new dimensions of compassion, and care. One can passionately desire another person; one can passionately desire a divine being. Ta erôtika possesses a vast range and a sacred symbolic dimension. Thus, even in antiquity, religion went elsewhere.

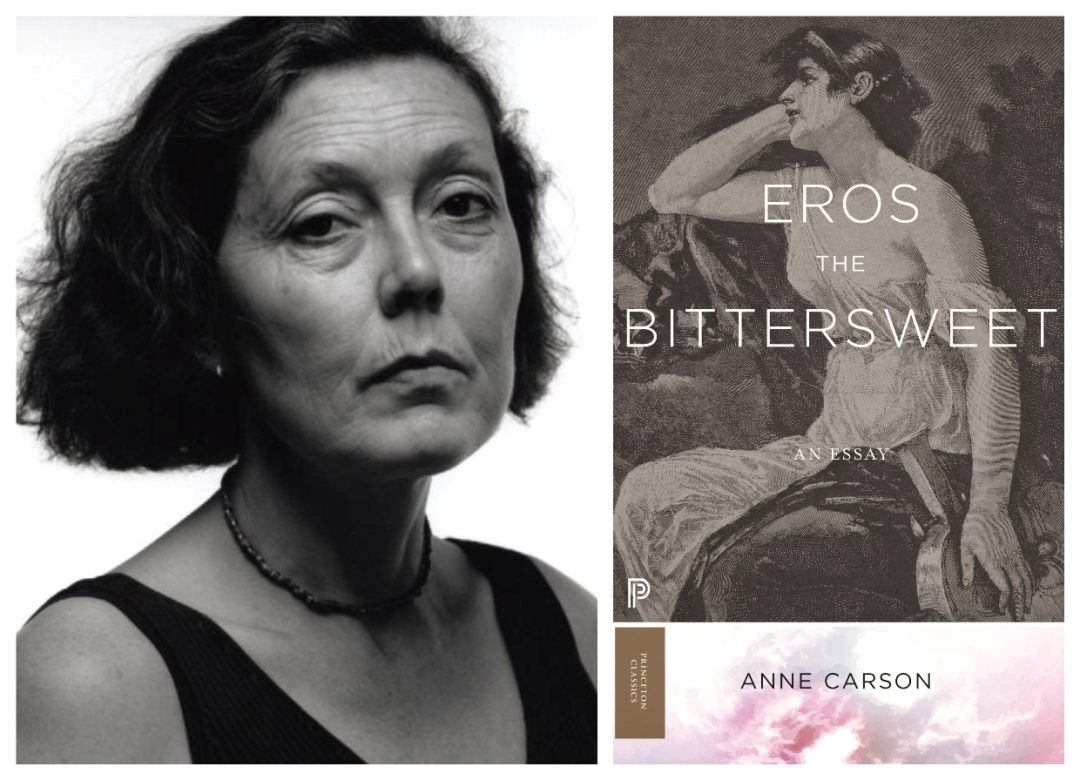

Anne Carson, whose Eros the Bittersweet I cited above, developed an entire philosophy of eros that was grounded in Sappho’s poetic fragments and Plato’s Phaedrus. She offers a lovely analogy between the wooing of knowledge and the wooing of love. Coming to love and coming to know both involve passionate desire; both necessarily transform and enlarge the self. These are experiences where the head and the heart are interwoven, and our attention becomes infinitely finer.

It would be hopelessly reductive to equate eros with sex, as some modern thinkers nonetheless attempted to do. We owe our modern conception of “sexual identity” to modern psychology, which became preoccupied with the concept in the later 19th century. The transformations involved in such a concept are extensive. Sex, after all, is something many people (not all) do. Sexual identity, by contrast, is something all people are (even “celibate” is a sexual identity).

The distinction between being and doing was a very significant one in ancient Greek philosophy. What I wish to point out is that our current version of the “culture wars,” at least in their sexual dimension, makes more sense if we pay attention to this distinction. Laws are designed to regulate activity, not identity. But the moral stakes of a debate necessarily increase when we are discussing our identity, who we are, rather than what we may or may not choose to do.

Ironically enough, when classical philology and psychology both emerged as university disciplines in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, then questions concerning Sappho’s sexuality became central, and newly controversial. Since she was from the island of Lesbos, and since she mused so passionately about the young women in her circle, the term ‘lesbian’ became associated with the new psychological category of sexual identity. Some Romantics lauded Sappho’s passions, whereas some Victorians found creative ways to de-eroticize her poetry, when they did not condemn it outright. This seesawing use of an ancient Greek poet to affirm or to counter contemporary moral views of human sexuality continued in subsequent centuries.

Michel Foucault’s four-volume History of Sexuality (1976-1984) attempted to tell that story. While it is a complicated story in Foucault’s telling, I think its moral is very elegant and quite simple. The sexual subject, Foucault concluded, is distinctively modern, a product of psychology and its interest in sexual identity formation. But the desiring subject is perennial. Sappho and Plato are two of desire’s most eloquent ancient proponents. As they knew well, eros changes the self, expanding its boundaries and its spiritual possibilities. We are rendered a larger and more encompassing self, one more capable of compassion and care.

What does the future look like for Hellenic Studies in US Universities?

In 1903, just seven years after the Modern Olympic Revival, the Sophomore women at Barnard College in New York City challenged the Freshmen women to a series of athletic and artistic competitions. Thus “Greek Games” were born at Barnard. They developed into an extraordinary cultural phenomenon, and were wildly popular with the broader public; they became one of the most sought-after tickets in Manhattan. The Barnard women dedicated the Games each year to a different Greek god, they composed music and poetry, they designed costumes, and even built chariots, all new for the competition each year.

In the revolutionary spring and summer of 1968, university students all across Europe and the US petitioned for radical changes to university curricula and other educational practices. At Columbia University, just across the street from Barnard on Broadway, university students occupied the administration buildings and held out for weeks before being forcibly expelled. Their demands were many, including: better wages for university staff; more just university practices of acquiring property in the Morningside neighborhood; disengagement of the university from its military contracts; and the creation of new curricular programs in African American Studies and Women’s Studies.

The student occupation at Columbia just so happened to begin on the week in April when Greek Games were scheduled to be held at Barnard College. In solidarity with their students across the street, the Barnard women cancelled their 1968 Greek games. The following year they cancelled Greek Games permanently, deeming them “no longer relevant” to student concerns.

At this historical remove, we can well understand what the Barnard women were thinking. They were rejecting the traditional ways in which Greek had been taught at Barnard and elsewhere since Classics was established in the 19th century and Greek Games were established in 1903. They rejected the antiquated rhetoric claiming Greek civilization as the “greatest culture” and ancient Greece as the unique “childhood of Europe.” They rejected the implicit classism and elitism of classical learning. They wished to replace these classicizing sensibilities with more multicultural and multi-ethnic ones. We have these students to thank for the creation of African American Studies and Women’s Studies departments throughout the US (and also in Europe). But one of the unintended consequences of these curricular reforms was the marginalizing of Classics and Classical Studies.

It was never an Either-Or proposition, but it began to seem that way. Now, more than a generation after those crucial curricular reforms, we are in a better position to re-frame these curricular proposals in the form of a Both-And question. There is no incompatibility between having robust programs in African American or Africana Studies, in Women’s Studies, and in Classical Studies.

For the past thirty years, the most successful Classics programs seem to me to have moved beyond strictly philological and strictly classicizing approaches to the ancient world, and to have harnessed the resources of anthropology, among other disciplines, to enable ancient materials to speak to more contemporary concerns. Particularly noteworthy has been the application of the categories of identity to the ancient world: race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, and class. Ancient Greece provides a marvelous and extensive archive of reflection on all of these concepts and concerns. I suggested an important dimension of Greece’s different-ness in its erotic reflections in my previous remarks, for example.

The goal now is to present Hellenism’s continued relevance in new terms: as decidedly cosmopolitan; and as an essential piece of World Heritage. That is how we have attempted to present Hellenism at Georgia State University under the aegis of our Center for Hellenic Studies. The proposal continues to bear fruit.

- John F. Callahan, ed., The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (New York: The Modern Library, 1995), 482-483, italics mine.

- Walter Kerr, Tragedy and Comedy (New York, NY: Simon and Shuster, 1967), 35.

- Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay (Princeton University Press, 1986), 39.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: ANCIENT GREECE | CLASSICS | HELLENIC STUDIES | POETRY | RELIGION