Yannis Palaiologos is a journalist for Kathimerini daily. Having completed his academic studies in Oxford (PPE and B.Phil in Philosophy), he started his career in journalism in 2006. He is a 2015-6 Marshall Memorial fellow for Greece and the 2012 Winner of the Greek edition of the Citi Journalistic Excellence Award. He has also collaborated in the writing of a series of satirical sketches and comic plays about the corruption in Greece during 2008-9 entitled “Mama Greece2”.

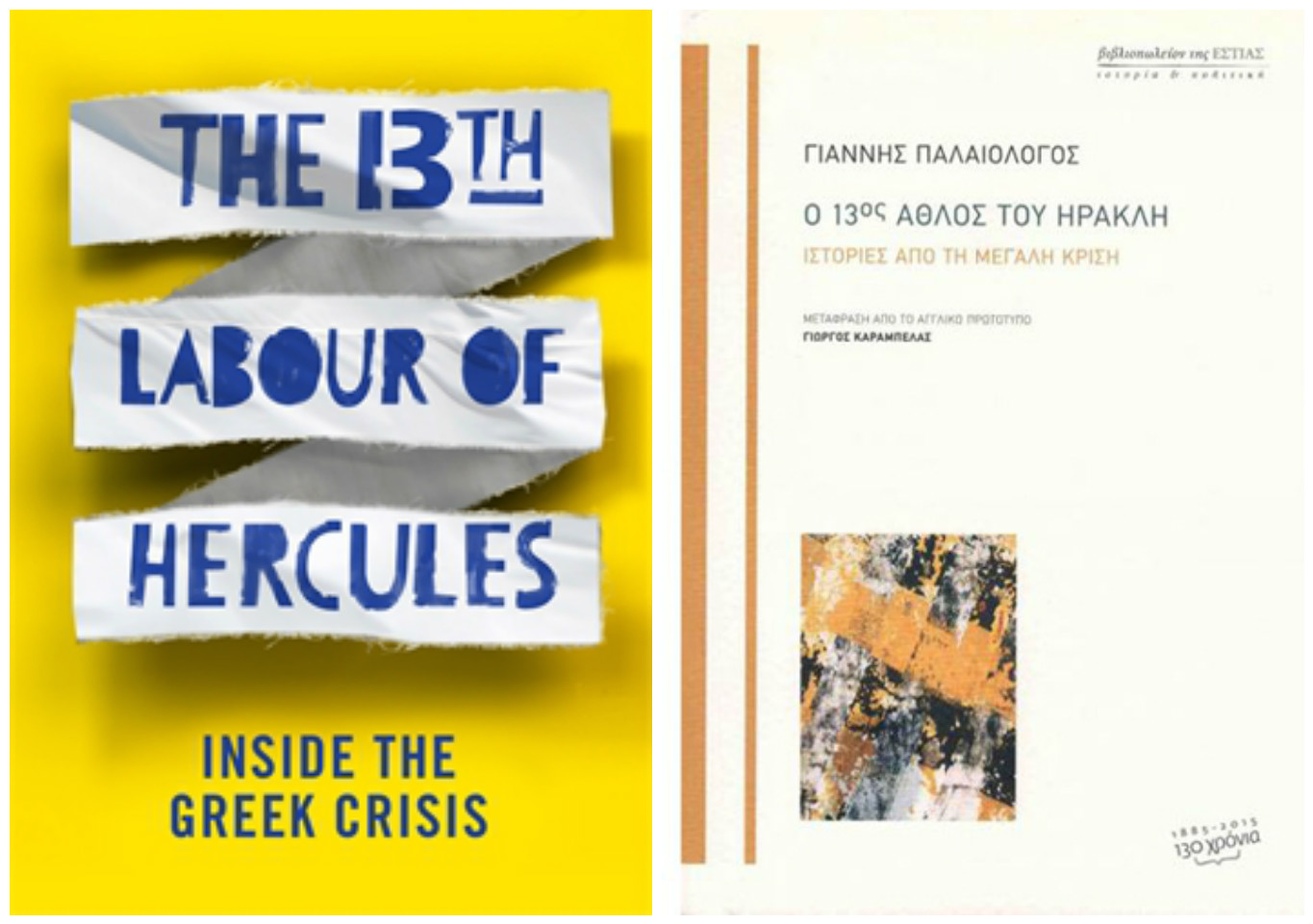

His book “The 13th labor of Hercules”, published by Portobello Books in 2014, was placed in the category “Debut of the Year” in the UK’s Political Book Awards and received very positive reviews. He currently works as a features reporter for Kathimerini Newspaper where he documents on stories related with financial, foreign and domestic political affairs, including interviews with major public intellectuals and political figures. He also contributes to other international media, among which The Wall Street Journal and to the websites of, Time magazine and Politico Europe (and, in the past, of the American Prospect and the New Republic) .

Yannis Palaiologos spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the current approach of the financial crisis by domestic and international Media, the issue of “mistrust” in crisis stricken societies- and particularly in Greece, the ‘vicious cycle’ of the Greek debt and the prospects of implementing Greece’s program agenda in the absence of “faith” in its principles, and the future of Greece in post-Brexit Eurozone.

What led you to choose a career in journalism after having pursued a demanding course in philosophy at Oxford University?

A lack of insight into the future, and a disregard of the advice of the serious people I consulted! To be slightly more serious, I discovered something of an affinity for writing, and I was always interested in public affairs – my first degree, aside from Philosophy, included the study of Economics and Politics. So I decided to give journalism a go – and have never really looked back.

How would you assess the way that the Greek Media report on the Greek and International Financial crisis? Are there any differences in their approach? How do they relate to one another?

Well, one critical difference is that Greek media have limited resources in foreign capitals, so much of their coverage of the global financial crisis is second-hand – we simply don’t have people on the ground. In the coverage of the homegrown crisis, I would argue that few media have been able to retain a decent level of objectivity in their reporting. It’s been an extremely polarizing period, and there has been no small amount of biased reporting catering to the interests of this or that political party, or of the specific business interests of this or that owner. The dramatic deterioration in the finances of most media companies, as bank loans dried up and ad revenue collapsed, and the fear of unemployment among journalists, have also contributed to the drop in quality. Having said that, there have been interesting and informative new efforts, in particular on the web, and many reporters have outdone themselves in offering honest, hard-hitting reporting, often in very difficult circumstances.

As for the relationship between the national and the intenational crisis coverage, I would say that the level of coverage of financial difficulties abroad depends directly on how significantly that crisis will affect Greece. So we cared a lot less about Gordon Brown bailing out British banks that we did about Ireland, Portugal or Spain.

Your book “The 13th labor of Hercules” which emphasized the lack of trust within the Greek society has been well received abroad. Is this “lack of trust” a particular Greek trait or does it apply to all crisis stricken societies?

I think lack of trust is a feature common to all societies with weak institutions, regardless whether they are in crisis or not. Weak institutions entail discretionary application of the rules: certain groups have enjoy preferential treatment by the state, whether its access to public sector jobs, first dibs on public contracts, immunity from the taxman or the public prosecutor etc. This breeds an unhealthy competition to enter the privileged groups, and a growing sense of disaffection among those left on the outside. Success is viewed with suspicion, as the product of the right connections instead of innovation and hard work. Mistrust becomes the common currency of everyday life. In times of crisis, the situation gets even worse, because the well-connected are better protected from the consequences, and do not really share in the burden of adjustment.

What does Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ rise to the helm of the main opposition party bring to the Greek political culture? What can we expect to be the new synergies amongst representatives of the “old guard” with the party’s new leadership?

Mitsotakis is a liberal who believes in evidence-based policy-making, and someone who seems personally dedicated to uprooting the clientelist system that has done so much to poison Greek politics and public administration. The fact that he was elected leader at all is positive news for Greek supporters of liberal reform and the open society. Of course it remains to be seen whether he can impose himself on his party, still dominated by stale thinking and the corrupt practices of the past. And even if he achieves that, he will still have to appeal to a wider public hostile to social liberalism and the free market, and navigate extremely treacherous international waters in order to put Greece on a path of sustainable prosperity.

In your analyses you often discuss the origins and future of the Greek debt. Do you think that the Greek economy can escape the vicious cycle of debt?

The Greek economy will find it very difficult to grow robustly given the fiscal straightjacket it is in with the third rescue programme. Primary surplus targets of 3.5% of GDP year after year from 2018 onwards put a real squeeze on economic activity. There are some encouraging signs on the horizon that this reality is finally sinking in official circles. The IMF has been arguing for most of this year that Greece cannot achieve these targets and that it needs further debt relief, such that it will allow to cut the surplus target to 1.5% of GDP. Yannis Stournaras, the governor of the Bank of Greece, has also argued in favour of a lower target, and even Eurogroup chairman J. Dijsselbloem has accepted that the current targets are not realistic. Berlin, however, remain silent on the issue – and keen not to discuss it before next year’s general election. So the escape from the vicious cycle seems some way off yet.

At the last Eurogroup meeting, Greece secured a deal with its peers following the adoption of its latest bill that included further taxes and more austerity reforms. Is Greece ready to follow a “conservative” economic adjustment plan led by a left government or is this a bet to be won by a centre-right political collaboration?

The current programme, as I explain above, is not sustainable. It needs lower surplus targets, which necessitate further debt relief. Having said that, I think that a liberal centre-right government, one which believes in privatization, free competition, flexible labour markets and so on, will be much better placed to implement the programme agenda, especially in looser fiscal conditions, than our current governing coalition. It’s very hard to make something this challenging work when you have no faith in it.

The pressure has increased for the EU to reinvent itself after the outcome of the UK referendum. How can we envisage Greece’s future in a changing Europe? What could Greece’s contribution be in a new European project?

At this point, with Britain in chaos and Europe in shock, it is hard to envisage anything. Nevertheless, we can say the following: if Britain’s referendum does not lead to some new, inclusive thinking among the European leadership, and especially the Germans, which will allow southern economies like Greece and – more importantly – Italy to prosper within the euro, then the populist backlash against the Eurozone and the EU will grow. There will be more referenda, and Greece will be a prime candidate for a voluntary departure. The best contribution we can make to a more cohesive Eurozone post-Brexit is to finally do the things necessary to modernize our public administration and increase the productivity and competitiveness of our economy. But these efforts will not be enough to keep us in the Eurozone if the dogma of permanent austerity is not meaningfully amended.

*Interview by Vassiliki Ch. Diagoumas

TAGS: CRISIS | EU POLITICS | GOVERNMENT & POLITICS | MEDIA