An exquisite exhibition, bringing together an impressive range of artworks by the acclaimed Greek painter Markos Kampanis, is currently on view at the National Library of Greece.

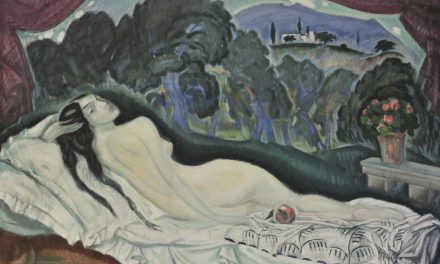

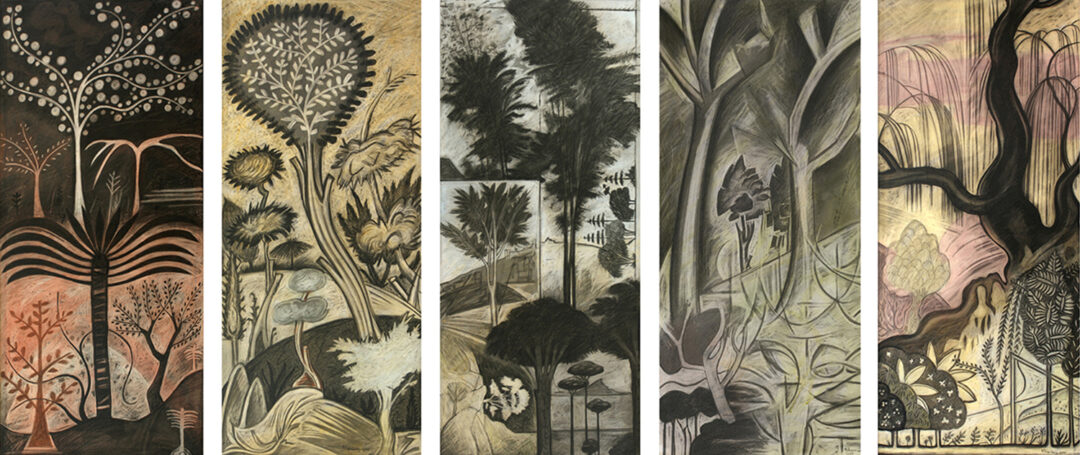

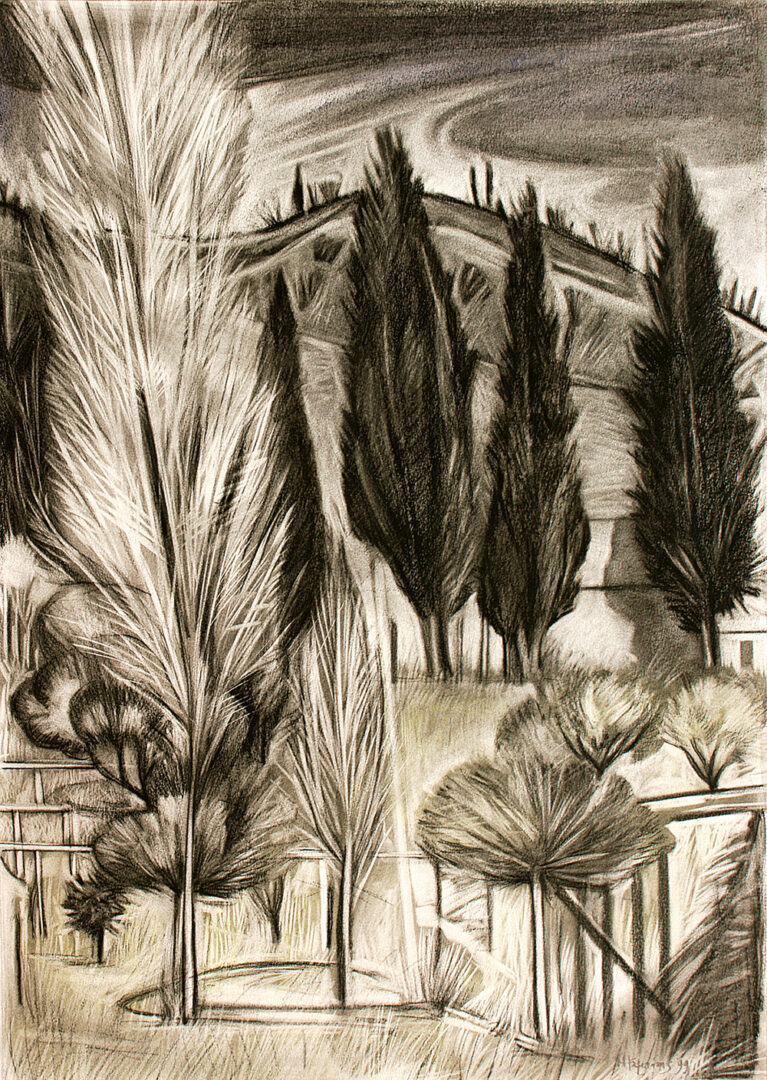

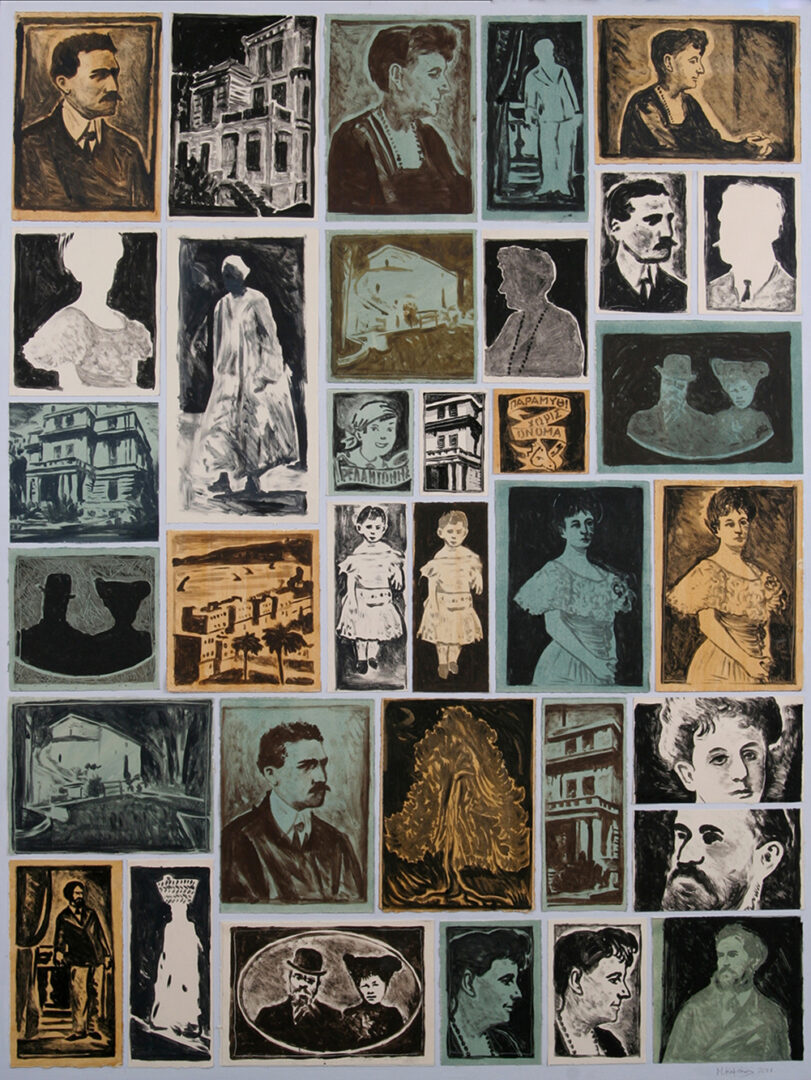

The artist’s work beautifully unfolds through painting, engraving, icons, and book illustrations, revealing an insightful, multifaceted, and artistically solid painter.

Organized thematically and inspired by the artist’s inquisitive approach to art, the exhibition captures a style that knows no boundaries, reflecting the painter’s unpretentious personality and generous spirit. Artistic expression is perceived as an evolving journey. Markos Kampanis skillfully integrates contemporary elements with traditional themes. His artworks, spanning across different times, reveal a distinct visual idiom.

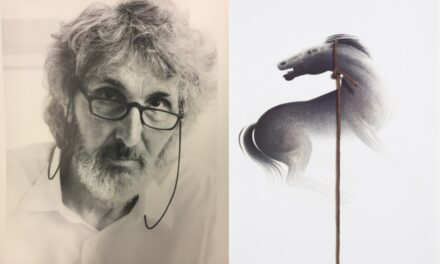

Markos Kampanis was born in Athens in 1955. He studied painting in London where he lived until 1980. He is mainly a painter but has also worked with printmaking, book illustration, church murals, and icons. He has extensively exhibited in Greece and abroad. In 1984 he participated in the 15th Biennale of Alexandria. His art focuses on landscapes, still life, and trees but also on the actual process of painting itself and the world of his painting studio.

Markos Kampanis kindly shared his thoughts about art and life with Greek News Agenda*.

Alternation is a feature that defines your art. How would you explain this constant, creative quest throughout your artistic trajectory?

This is due to my psyche and to the fact that I am not interested in creating a recognizable style to serve it. I like to experiment and explore variations not only in art but also in life itself. A typical example is my musical preferences. The very same day, I can easily listen to Callas or Kazantzides, hard rock or medieval madrigals, and pre-classical music or Indian music without feeling confused. In any case, I am more interested in ethos than style.

You have studied in London. In what way, your stay there has contributed to your artistic development?

I believe the time I spent in London defined me to a great extent. I just loved the city, the teaching system, and, of course, the daily contact with museums and exhibitions. I learned a lot in London. The academic perception was in line with my temperament, I fitted right in. It focused mostly on the daily, disciplined engagement with painting rather than what we often call “inspiration”, a situation I don’t believe much in, anyways. Furthermore, we were not limited to a single teacher and we were exposed to a variety of different views and techniques.

At some point, in the 90s you visited Mount Athos. How did it influence you, as a person and as an artist?

I have always been interested in Byzantine painting, both as an aesthetic concept and as content. Therefore, I had to go there once to see in person what I had admired in books. That was the occasion. Then I became enchanted in a way and began frequent visits. As a result, I had the opportunity not only to paint what I saw. Ι was also commissioned to do some work there, mainly murals, but also to edit books and publications. I have now developed a very close relationship with Mount Athos, both at a personal and artistic level.

In your works one can trace elements of the Byzantine tradition, the influence of Spyros Papaloukas, and, at the same time, more recent artistic styles. What, in your opinion, were the most important influences on your artistic idiom? Would you say your art belongs to a specific artistic movement?

I do not think it does. There are no clearly defined movements these days anyway. Papaloukas certainly had a great influence on me; after all, I have studied his work extensively through books and exhibitions. He is a painter who appeals to me not only aesthetically but also ideologically in the sense that, based on the Byzantine tradition, he created his own unique contemporary visual language.

Let’s not forget that he spent a year painting on Mount Athos. But there were certainly many other influences. I have always liked and studied painters who have nothing to do with my own visual idiom. I would add that the Byzantine aesthetic tradition has a lot in common with all modernism. It was not only Papaloukas who argued that Byzantium had the answers to the problems of modern painting. Many modern painters have also agreed to this, not only theoretically, but also through their actual influences. From painters like Matisse, Klimt, and the English Bloomsbury group to the Russian avant-garde.

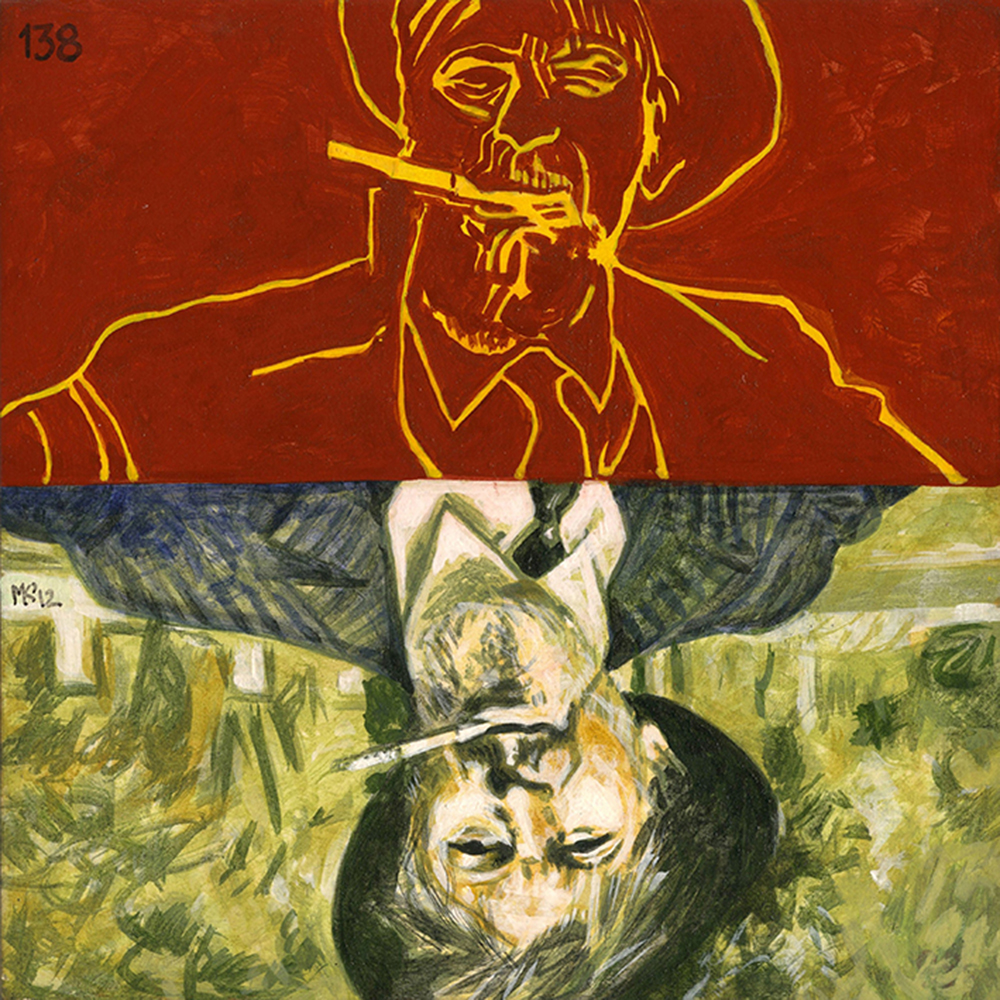

Looking at your art, especially “365” and “The Museum of Trees”, one can see incredible diversity. The overall result also reveals an artist who is organized and disciplined. How did you manage to impose on yourself the rule of creating an artwork every day for 365 days and how did the idea of telling the story of art history through trees come about?

I am a very organized person, that is true. Studying in the UK certainly contributed to this, but also my interaction with the monks on Mount Athos, which is a disciplined society. Discipline for me is not opposed to freedom. The history of art through the Trees reflects my love of nature on one hand and my parallel interest in art history and theory on the other.

I would say that at the same time, I am a painter of nature, of a studio and libraries. In all three, I feel at home. The narration of the trees through timeless artistic representations has also allowed me to interact with seemingly different or even hostile aesthetic approaches and to discover common elements in approaches that at first glance did not seem to fit together.

Your art, almost emphatically, focuses on landscapes and still lifes. Where does the human figure stand in your work?

The human figure has indeed only occasionally caught my attention. However, I would argue that my engagement with ecclesiastical art, whose subject matter is almost exclusively the human being, in a way, restores the lack of anthropocentric themes in my painting.

After all, I believe that what matters in painting is the way and not the subject. To further elaborate on this, let me tell you something about the new series of works I am already preparing for the next exhibition, which will take place almost immediately after this retrospective. My upcoming exhibition pertains to the journey and adventures of Odysseus. Nevertheless, I abstractly approach the Odyssey. The human figure is absent.

Your works are in a constant and coherent dialogue with tradition and several artistic movements of the 20th century. What do you think of contemporary art? What is your reaction to installations, performance art, etc. as opposed to representational art?

I have no objection to any form of art as long as it is authentic. Representational as well as non-representational art equally appeal to me. Both approaches have produced great painters as well as bad ones.

Regarding installations or performances, I would say, they are definitely beyond my immediate interests. Although some amazing works have been created in this field, still it does not appeal to me. In my opinion, it lacks aesthetic emotion and interest in what we call “beauty” since what they usually prioritize is their ideological or social content.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

TAGS: ARTS