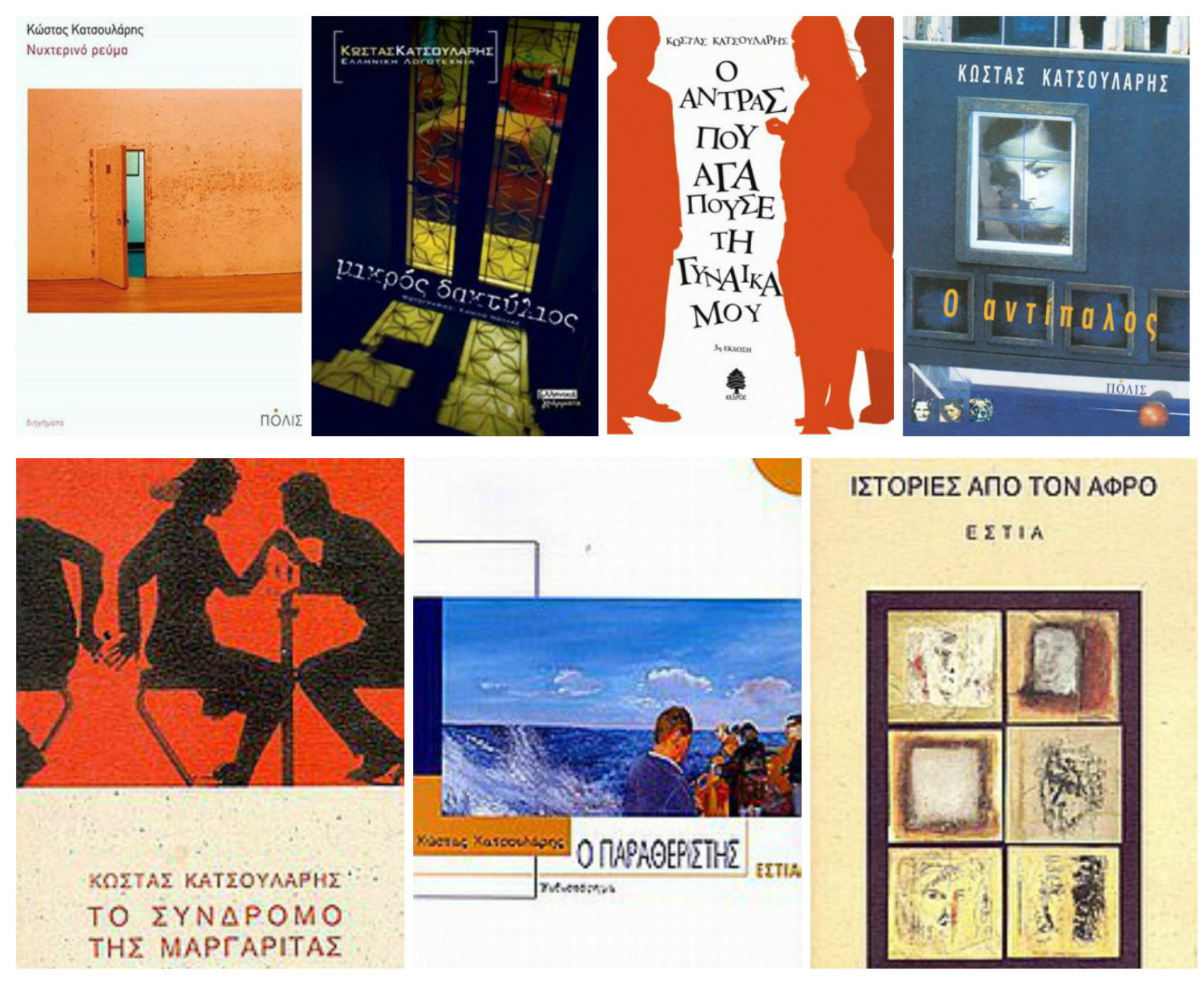

Kostas Katsoularis was born in Arta in 1968. He studied in Athens, Thessaloniki and Paris. He is the author of three novels – To Syndromo tis Margaritas (1998), O Paratheristis (2001), O Antipalos (2005) – two novellas – Istories apo ton Afro (1997), The Man who Loved my Wife (2010) and two collection of short stories – Mikros Daktylios (2007) and The Night Current (2015).

His short story, “The shoes and the Trousers”, from his collection Mikros Daktylios, was included in ATHEN. Eine Literarische Einladung, published by Wagenbach in 2008. His novella, The Man Who Loved My Wife –a deep exploration of male jealously– was translated into Turkish by Heyamola Yayinlari in 2011. His latest book, a collection of short stories titled, The Night Current was the recipient of the Anagnostis Literary Review Award 2016 for Best Short-Story Collection. The novella “Dead Dog at Midnight”, which forms part of the collection, was translated into English, Spanish and Hebrew for online literary magazine, Maaboret, The Short Story Project in June 2016.

Kostas Katsoularis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book, Athens as the backdrop of his stories, his heroes who “deal with reality as a mystery that needs to be resolved”, while also commenting on what makes a good book, his stance towards literary critics, and people who read literature, “an ‘anthropological type’, a ‘species’ in danger from the onslaught of easy readings and of technological facilities that indeed need some kind of protection”.

Your short-story collection Night Current has just won the 2016 O Anagnostis Literary Award for Best Short-Story Collection, while one of the stories, “Dead Dog at Midnight”, was the first Greek short story to be selected, translated and published by the Short Story Project. Tell us a few things about the book.

The Night Current is composed of four, quite long short stories. One of them, the one you mentioned, “Dead Dog at Midnight”, would come close to being called a novella. I begin with this observation, given that this is rather unusual in Greek literature, where there is noted preference for shorter stories that in a wink of an eye narrate their subject. On the other hand, I am more attracted to prose that focuses on characters, plot, on multiple levels, on the development of secondary characters. All four stories are irrigated by the big and mysterious current of realism, even if internal realities are more highlighted than social ones or even dictate them.

Amir Tzukerman has described you as an “Athensnographer”, since the plots of many of your stories take place in the heart of Athens, and your central characters are residents of the city centre. What do you find intriguing in Athens? How has the Athenian way of lifeevolved in the last decades?

It is true that all four short stories, as well as those in my other books, take place in Athens and are in an open dialogue with the city in multiple and unforeseen ways. I live in Athens and I like to think of the city as a «scene» where all the action relating to my characters takes place. Very often, I like to restrain them in city centre, in places of strong social and historical impact, like Exarcheia, Kolonaki or Kypseli. That said, I would not adopt the characterization of Athensnographer for myself. The term implies a sort of genre approach, a kind of old fashioned prose which I do not think suits me.

In his review, Alexis Panselinos wrote that you are “a master in describing people”, commenting on your accuracy in “understanding and expressing the inner voices of different characters”. How would you characterize the protagonists of your books?

Alexis Panselinos, a very good writer himself, was quite courteous and generous in his comments. Anyway, if there is something specific that characterizes my heroes it is that they deal with reality as a mystery that needs to be resolved. Usually, towards the end of the story – whether a short story, a novella or a novel – my heroes realize that the enigma they are trying to solve does not have a single answer and that everything is constantly changing depending on what stance they take on every occasion. On top of that, they are people with moral concerns that try to do the right thing, despite the confusion they are often led to

“Good books are living organisms, they change as we do. Each time we open a book is never the same as the previous one”. What makes a good book? How would you characterize the new generation of Greek writers? Have they managed to overcome stereotypes, ‘writing’s biggest plague’?

I absolutely agree with this ascertainment. This is what books do. Books actually reborn each time they are read, which is something wonderful because it gives good books the chance to live hundreds or even thousands of lives, to converse with many and very different people through time. In that sense, ‘good books’ are those that can unlock various and quite unexpected readings. They are the books that challenge the reader to talk on topics apart from their subject, topics that their reader would never even think about if it had not been for a certain book. Finally, as far as contemporary Greek writers are concerned, I believe that we are going through a phase of fermentation that has already led to the production of very promising results.

You have stated that the quality of book reviews in a country reflects the quality of its literary production. What is your personal stance towards literary critics? Do negative reviews influence you?

Not all literary critics are the same, as not all writers are the same. Some critics are the best and most profound readers I know, who write reviews that are a pleasure to read, even when they include negative comments. There are others, fewer, who use clichés, as if they write about the same book ever time. I follow critical discourse closely and I am quite concerned about its retreat, while brief reviews and book presentations or notes not requiring full justification are more frequent. More traditional critics, although they may have many flaws, are by far more preferable.

What about book readers? Are they “a species facing extinction”? If this is the case, what may or should be done at an institutional level to ensure their ‘survival’?

Readers in general are not a species under extinction. The question concerns a certain number of readers, those who read literature. Those readers are able to receive a text that does not flatter them or that might even create a feeling of estrangement but in the end rewards them abundantly. I refer to those book lovers who read a considerable number of books every year and do not jump from page to page with their mind flying elsewhere. In that sense, people that read literature – a few thousand in Greece – are more or less an “anthropological type”, a ‘species’ in danger from the onslaught of easy readings and of technological facilities that indeed need some kind of protection. That ‘protection’ is not something that can be given in a simple way. Multiple interventions are necessary from state institutions, with campaigns and coordinated actions similar to those the National Book Center used to organise in the past.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE