Visual artist Theo Bargiotas presents the outlandish universe of his latest endeavor Theogony, currently on view at Alma Contemporary Art Gallery. His paintings allude to a post-apocalyptic setting where humans, depicted as helpless, tragic, psychedelic creatures are struggling with a nightmarish situation. At the mercy of this eerie world, his characters find themselves desperately seeking God.

Intentionally ambiguous, Bargiotas’ works of art are open to various interpretations. The emerging dialectic between naturalism and symbolism invites us to explore various aspects of existential issues and spiritual challenges. Theogony‘s uncanny world reveals the artist’s talent and intentions. Like a storyteller, Bargiotas creates vibrant narratives that blend styles, colors, and emotions, capturing an energy that is strongly evocative and compelling.

Theo Bargiotas was born in 1982. He grew up in Tennessee and Athens, Greece. He graduated from The University of Athens School of Law and holds an LLM from Strathclyde University School of Law. He worked as an attorney in Athens until 2011, when he decided to dive ιντο the world of Art. He graduated from the Athens School of Fine Arts with a distinction and went on to earn his MFA in Fine Art from The University of Oxford. He moved to the American south, Baton Rouge, Louisiana and taught studio art at Louisiana State University, while working on his Doctorate degree research concerning a philosophical analysis of genetics and cloud storage. He has participated in numerous exhibitions in the US, the UK and Greece and published two books (Pernilongo 2012, Marmelada, 2014). After receiving his Doctor of Design, he moved back to Athens, Greece where he now teaches painting and keeps on fabricating myths and drawing them… just like he always did.

Theo Bargiotas talked to Greek News Agenda* about his ongoing exhibition, his pseudo-religious narratives, his beloved back porches of the American South, the absurdities of the world we live in and AI in the field of arts.

Your art, predominantly anthropocentric, refers to an uncanny universe. Its people are passive, frightened. Do you see any similarities between your works and the world we live in?

As a painter who loves creating narratives and populating them with people, I always keep in mind that these inhabitants need to have a personality, inner thoughts, fears, doubts and hopes. I have a special place in my heart and my paintings for facial expressions. They are certainly the gateway to comprehending people. I am especially fond of moderate expressions, not exaggerated appearances. Those in between gazes that you can’t quite read and not an over-the-top gape or scream which is literal and lacks any interpretational wiggle room for the viewer. Sometimes, the stances in my paintings contradict the facial expressions: Baroque poses and glary eyes, movement and theatrical narrative but faces that don’t know exactly what is going on. This way the viewers can place themselves in the painting, in the story and perhaps this is the best way for a storyteller to be heard and for myths to be believed.

As the title of your exhibition indicates, the search for God has a central role in your works. Do we need to believe in something beyond ourselves?

I have created a pseudo-religious narrative about two factions of young people (Lord of the Flies obviously has a heavy influence as well as the works of Henry Darger) which have been arbitrarily placed on a somewhat barren terrain. They are both trying to create or capture a being to believe in and transform that being into a kind of totem, (whether that creature wants to or not is a whole other story).

There are layers of allegory in this series, the most prominent for me being that of creation. How does a creator go about creating? By incorporating elements from other divine creations around him, by fabricating novelties out of thin air or perhaps both? This is an issue that has been ringing in my head a lot this past year because of the new AI text-to-image tools that have been developed and I have experimented with.

Yes, of course, there are heaps of legal issues regarding intellectual property (let the lawyers lose sleep over those) but there are also essential conceptual issues pertaining to self-contained human imagination vs collective consciousness (images generated via visual data banks) that have amusing connotations such as that of the artist that signs their work and flaunts their personal style (which was a concept reborn in the Renaissance) vs the artist who acts as a conduit for a higher power in Byzantine iconography and thus stylization is forbidden.

All these thoughts and the research I’ve been conducting for the past year and a half or so were the underlying inspiration for the story portrayed in the series Theogony, but at the end of the day all these serious, serious concepts are just an excuse to paint.

How important is observation for you during the creative process?

The occupants of my paintings are just like the inhabitants of the actual world surrounding us. There is nothing surreal or out of this world about the scenes I portray – perhaps a glimpse of the uncanny or an inkling of the absurd – and there is no doubt that the world surrounding us is even more absurd than the stories I tell.

In any case, that is what a storyteller must do: observe things around him and reflect these images back at the world through his personal vision. I have to agree with Werner Herzog that “that’s what we are, we are thieves. We get the loot from the most spectacular or scary places. We’re bank robbers. Just hit and run.”

What artistic movements can be traced in your art?

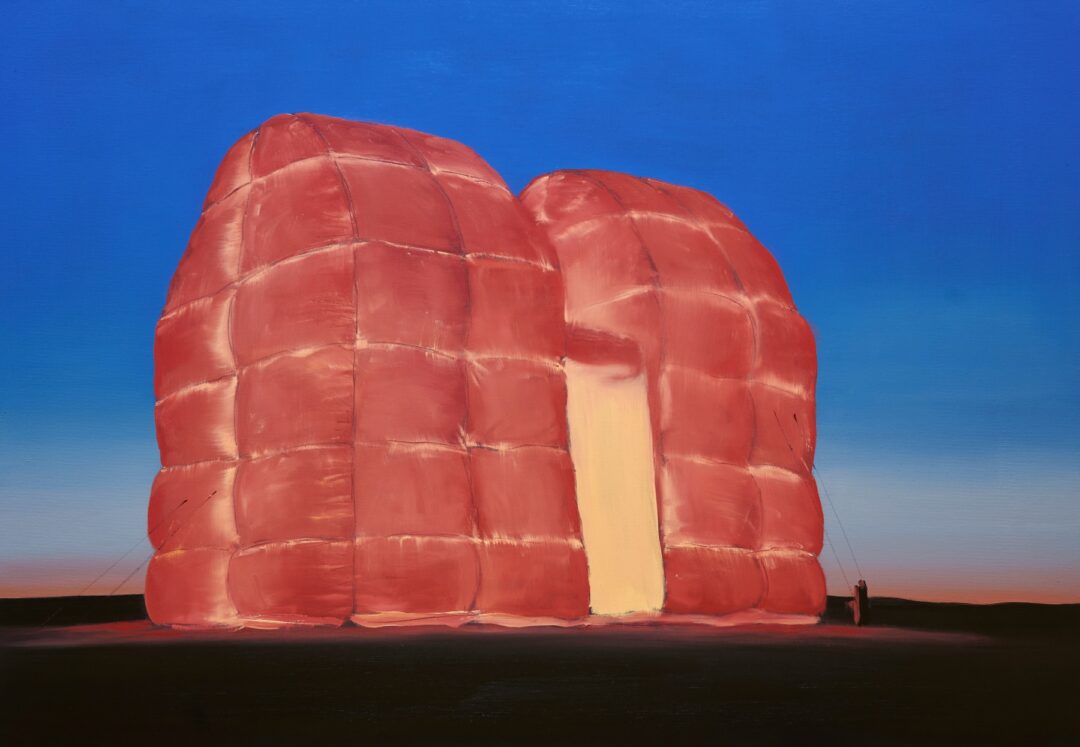

I certainly do love homages! In this series for instance, I pay tribute to many of my favorite painters such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder (I adore Flemish Renaissance grotesqueness), Minoru Nomata (architectural paintings of buildings which are neither here nor there), Henry Darger (who created an absurd universe where children are at war with grownups), Millet (the insinuated religiosity of paintings like L’ Angélus), Moebius’ heavily populated landscapes in works such as 40 days in Desert B or Sidney Nolan’s outrageous tales of a deified thief (Ned Kelly) set in Australia’s vast horizon.

You have lived for several years in the United States. How has this time had an influence on you as an artist?

I grew up in the South of the United States, in Tennessee and then went back and studied and worked in Louisiana, and in between I have lived most of my life in Athens, Greece so obviously there is a recurring theme of the South in my life. And in the South, whether in Baton Rouge, Louisiana or Athens, Greece, religion is a recurring theme. I guess that it’s not surprising that some of my favorite authors are from the South as well. Harry Crews, for instance, who wrote The Gospel Singer, a tale about a (deceiving perhaps) faith healer in Enigma, Georgia but also Kazantzakis whose work is richly saturated by themes of religiosity and God though in both cases through a relentlessly secular prism and elegant humor. On a personal level, having lived in the South, has made me prone to sit on back porches for hours looking at the sky and listening to chirps, twitters, squawks and buzzes.

As a lecturer in the Department of Digital Arts and Film and as a contemporary visual artist, you have obviously experimented with technology. How do you perceive the role of AI in your field?

I try to incorporate digital elements of image making into my curriculum at the University, without jeopardizing craftsmanship. Luckily, I teach both drawing/painting courses and also 2D composition courses so there’s a lot of space for both worlds, the analog and the digital.

For instance, in one course this semester, students are asked to create movie posters using an array of tools from scissors and glue collages, painting, printing, digital manipulation and yes, AI. It’s important that young visual artists experiment with these contemporary tools, even if they decide to ignore them later on. There is a surprising amount of demonization among art students right now concerning AI which is troubling, and that’s why it’s even more crucial for them (and all artists and creatives) to at least understand what is transpiring at the moment on the AI front and then knowledgably decide if any of these tools could be useful. I personally have found them very useful for creating reference material for some of my paintings and at the same time appalled by images and videos which are exhibited as “AI art”, images obviously lacking any craft, knowledge or effort.

The more tricks a visual artist has in their toolbox, the richer their images can become. In the end beautiful visual art depends on personal research/experience, theoretical knowledge of the field and honest infatuation with the world around you combined with a certain skillset as a medium to communicate your stories. I don’t think generating an alligator with the help of AI for a painting is an issue. Plus, I checked, and alligators are expensive to ship to Greece from Louisiana just to pose for one painting.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

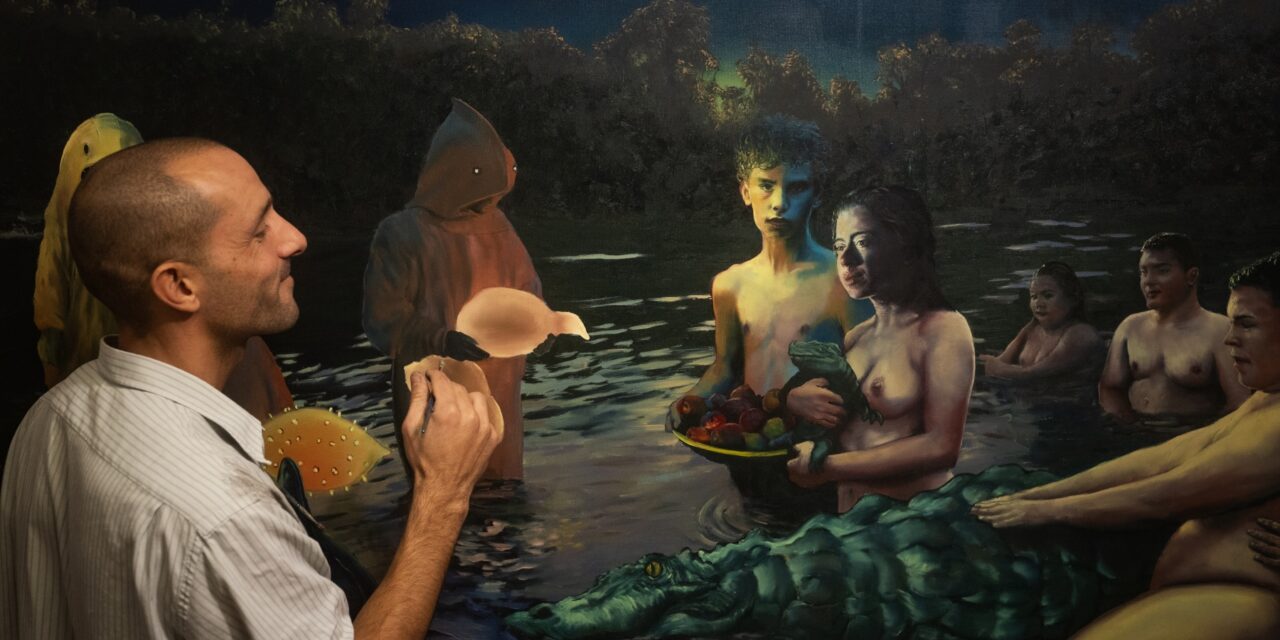

Intro image: Theo Bargiotas in front of his painting Bayou Betrothal ( La Sposa dell’Alligatore)

TAGS: ARTS