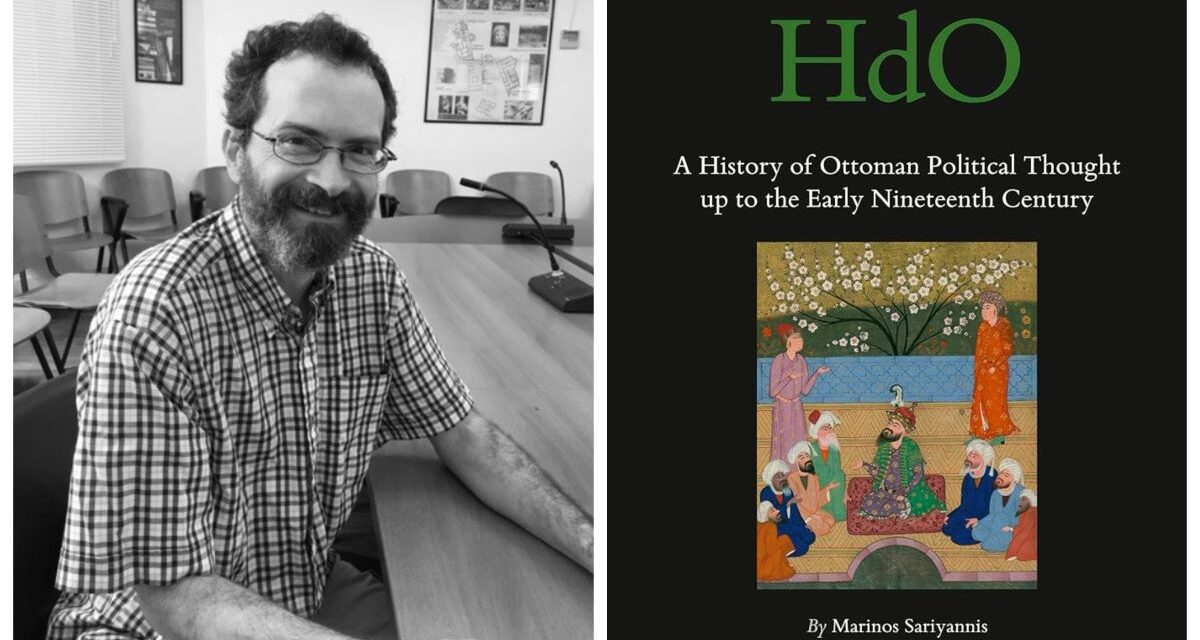

Marinos Sariyannis has been working as a researcher at the Institute of Mediterranean Studies/FORTH since 2007, specializing in Ottoman social, cultural and intellectual history. He is deputy director of the Institute for Mediterranean Studies/FORTH and member of the Editorial Board of Archivum Ottomanicum (Wiesbaden) and of Bulletin de Correspondance hellénique moderne et contemporain (Athens – Paris). He has published more than fifty articles and chapters in journals such as Turcica, Archivum Ottomanicum, International Journal of Turkish Studies, Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient, Turkish Historical Review, and others. His monograph entitled “A History of Ottoman Political Thought up to the Early Nineteenth Century” was published in 2019.

Sariyannis spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the shift in the perception and study of the Ottoman past in Greek historiography and the emergence of a new generation of Greek Ottomanist scholars, whose ease with both Greek and Ottoman sources allows them to examine Ottoman realities in the Greek lands in a multifaceted way; on the main fields of Ottoman Studies research in Greece (urban history, agricultural realities, the peculiarities of islands, the commercial and maritime activity, monasteries); on the project GHOST, an effort to explore the meaning and content of what the Ottomans meant by “marvelous”, “strange” or “extraordinary”, and whether the Weberian notion of “disenchantment” can be applied in an Ottoman context; and finally, on his monograph “A History of Ottoman Political Thought up to the Early Nineteenth Century,” claiming that “the Ottomans had their own share in the ‘Age of Revolutions,’ although a very sui generis one.”

Up until the 1980s-1990s, the Ottoman period (termed Tourkokratia or ‘Turkish rule’) was seen generally by Greek scholars as a period not worth studying. Why do you think this perception had remained prevalent for so long in Greek historiography? What was the shift that caused this perception to change?

Undoubtedly, this perception was primarily a result of the prevalent nationalist foundations of Greek historiography. Greek historians felt their duty was to study the development of the ‘Greek nation’ throughout the centuries; the Ottoman period was considered a lacuna of sorts, a dark space of yoke and repression between two brilliant periods of independent glory (the Byzantine Empire considered a predominantly Greek formation). Being a pillar of the ideological foundations of the Greek state, this concept remained prevalent for more than one hundred and fifty years. The Ottoman period was seen as a foreign rule, an occupation that lasted centuries and prevented any kind of intellectual and social development, during which nothing mattered but the efforts of the Greeks to revolt.

By the end of the 1970s, however, after the fall of the nationalist military junta, a new generation of historians had begun studying this period in its own right, focusing in its economic and social realities and trying to take into account the few translated Ottoman sources. It was in this context that the first generations of Ottomanist scholars, trained in the UK, the USA, Austria or France, begun exploring and publishing Ottoman archives on the history of the Greek lands. Some of them inspired young students to pursue Ottoman studies, and with the help of some financially happy years that allowed several posts of Ottoman history to be created in universities and research centers all along Greece in the 2000s the field is now thriving.

What did the Greek perspective bring to the field of Ottoman studies? And on the other hand, how has the inclusion of Ottoman studies influenced our understanding of modern Greek history?

The main advantage of Greek Ottomanists over their peers is exactly their ease with both Greek and Ottoman sources, which allows them to examine Ottoman realities in the Greek lands in a multifaceted way. Their emphasis on the hard data is dictated both by their training in the intellectual climate of modern Greek historiography and by the nature of the Ottoman sources, i.e. mainly tax registers or judicial proceedings. The combination of Ottoman administrative sources and Greek communal narratives and archives leads to an emphasis in “history from below” and has perhaps contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the coexistence of religious groups under Ottoman rule. On the other hand, the work of Greek Ottomanists showed that no history of the Greek lands can be written without studying Ottoman sources and without taking into account not only the Ottoman institutions, but also non-Greek populations. What is more, the Ottoman period is not any more seen as a static context of a dynamic Greek nation; we now understand that the institutional and social realities of the Ottoman Empire developed considerably from the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries.

What can you tell us about Ottoman Studies in Greece now? What are the principal fields of studies?

Ottoman studies are blooming in Greece: there are professors and researchers of Ottoman history in almost every university and research center, and postgraduate students often choose an Ottomanist direction. Greek Ottoman scholarship has been predominantly occupied with economic, demographic and social history: this is only too natural, given the multitude of such sources preserved in Greek archives. Urban history, agricultural realities, the peculiarities of islands, the commercial and maritime activity, monasteries – these have been the main topics that occupy Greek Ottomanists. Furthermore, some scholars have addressed wider topics that apply to the Ottoman Empire as a whole, such as revolts, centre-periphery relations or issues of cultural and intellectual history.

You teach at the Department of Ottoman History at the Institute for Mediterranean Studies/FORTH in Rethymnon. How has the history of Crete during influenced research in the Department? What are the particular sources that a specialist in Ottoman history can study οn the field?

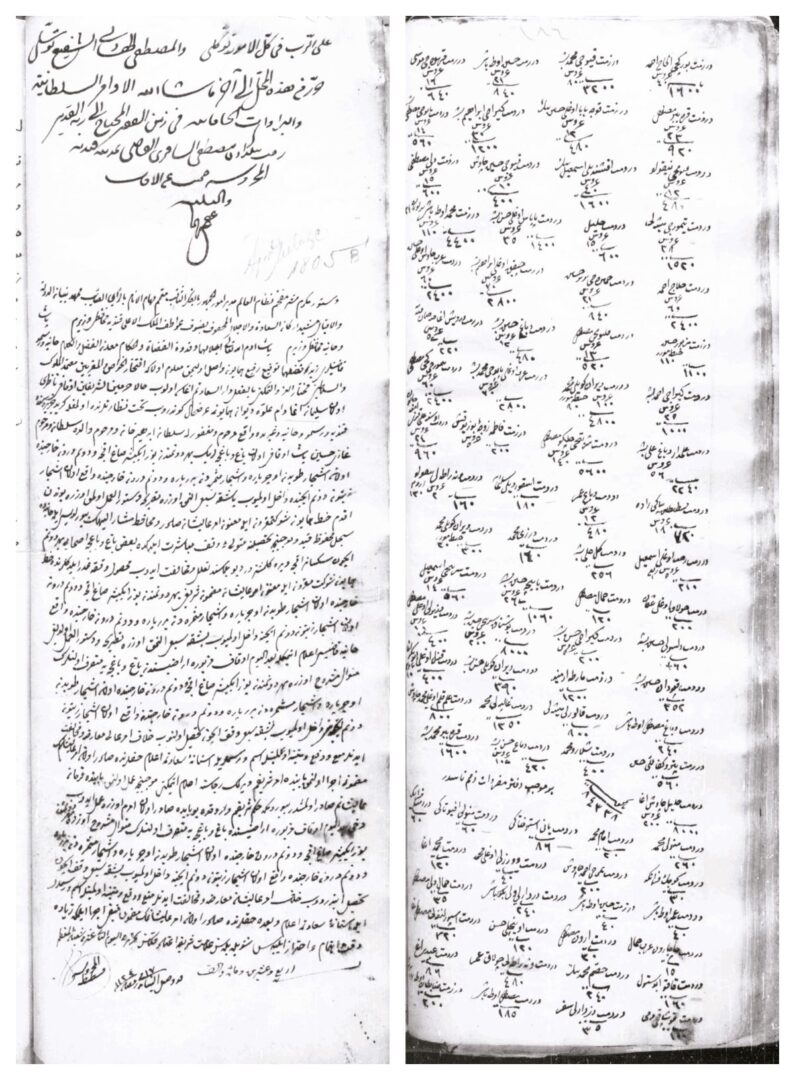

To be more precise, I only teach in the postgraduate program which is run jointly by the Institute and the University of Crete; the Department at the Institute mainly deals with research, rather than teaching. That said, ever since its creation in the mid-1980s the Department has been focusing in Cretan history, engaging in a long-time project that aims to publish the huge Ottoman judicial archive of Iraklio/Kandiye (Candia) since 2000. All of the members have also dealt with various aspects of the history of Ottoman Crete. However, in the last ten years our research directions have moved toward other sources and topics as well, ranging from the study of other places in Ottoman Greece to the janissary networks in the Eastern Mediterranean, not to mention my own musings in cultural and intellectual history. At any rate, Crete remains a favorite object of our research, not least because of the wealth of archival sources available. These include the voluminous judicial registers, but also tax registers and other documents preserved in Istanbul.

Since 2018 you direct the project “GHOST – Geographies and Histories of the Ottoman Supernatural Tradition: Exploring Magic, the Marvelous, and the Strange in Ottoman Mentalities”. Can you tell us more about this fascinating premise and the insight it brings to Ottoman studies?

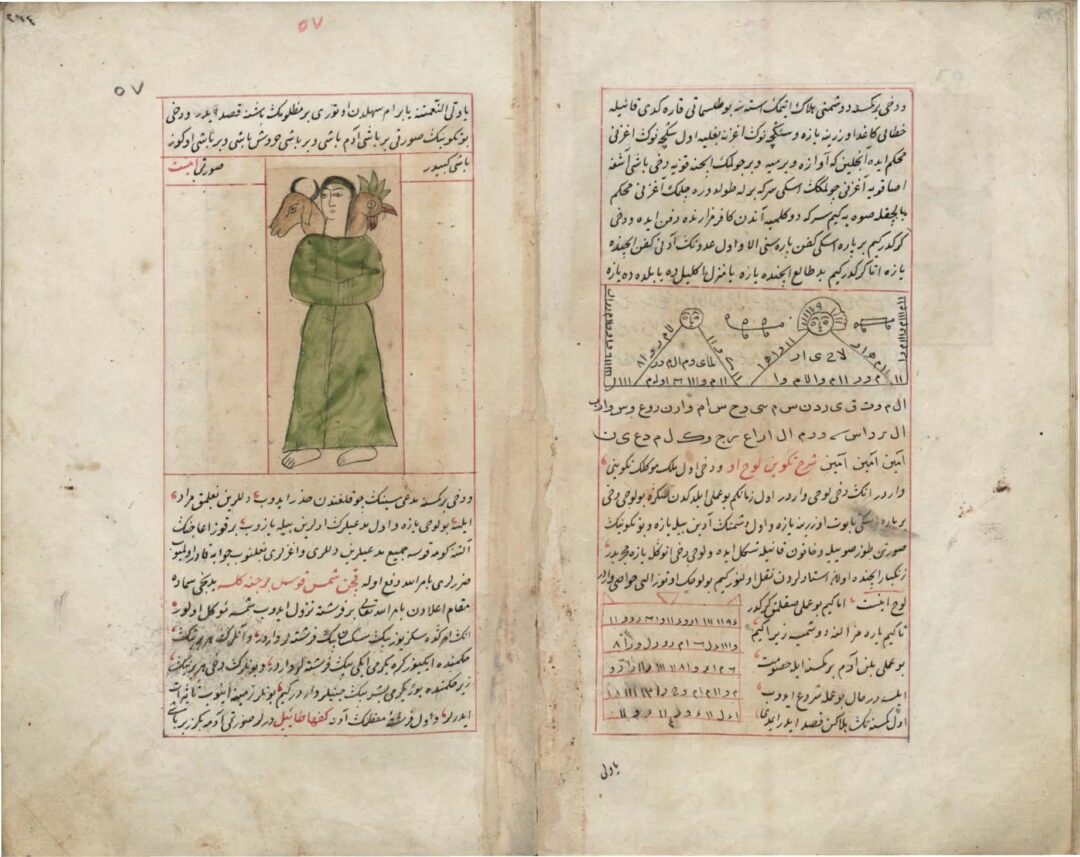

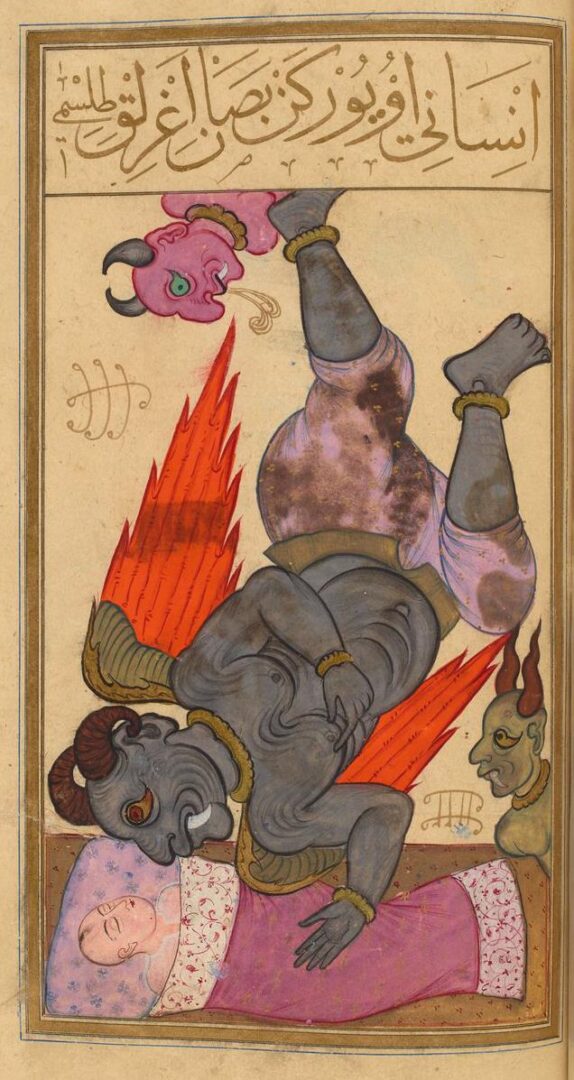

The GHOST project, which now comes toward its end, is an effort to explore the meaning and content of what the Ottomans meant by “marvelous”, “strange” or “extraordinary”, and, vice versa, the correspondent notions that covered what we now describe as “supernatural/preternatural” and “irrational”. We seek to specify the Ottoman attitudes against beliefs in such phenomena or practice of such methods, both holy (e.g. miracles of dervishes) and suspect (magic, witchcraft). Various authors might attribute such phenomena to actions by the jinn or, alternatively, to a secret interaction of the cosmic elements. A major aim of the project is to analyze the various ways changes took place from the mid-seventeenth century onwards: for instance, we tried to study whether certain phenomena were pushed from the field of “inexplicable” to the field of “marvelous”, whether we can speak of any trend to “rationalize” the image of the world, or, in other terms, whether the Weberian notion of “disenchantment” can be applied in an Ottoman context.

To this aim, we sought to trace the semantic shifts in terms denoting nature, miracles, magic and so forth, examining miracles, dreams and the various beliefs concerning the role of stars and the homologies and hierarchies of the microcosm and the macrocosm. There is also the “preternatural”, i.e. what is deemed natural (not miraculous) but inexplicable (the “paranormal” in modern terms): wonders of the world, hermetic knowledge, the jinn, and of course the shifting ways to interpret natural phenomena. Furthermore, we analyzed efforts and techniques designed in order to establish human control over such phenomena: in other words, Ottoman occult sciences, such as divination, magic, astrology, alchemy and so forth.

The results of the project can be seen in more detail in our publications: mainly, the papers published in our online, open access journal called “Aca’ib: Occasional papers on the Ottoman perceptions of the supernatural” and in a monograph I wrote, Ottomans and the Supernatural: Nature, the Hereafter, and the Limits of Knowledge in the Ottoman Empire, which is hopefully to be published soon.

Υou are the author of the book “A History of Ottoman Political Thought up to the Early Nineteenth Century.” What are your thoughts on the existence of “Ottoman Enlightenment?” Can you identify any enduring legacies of Ottoman political thought in modern political theory or practice?

This book was the result of another research project, back in 2014-2015, which sought to trace the history of Ottoman political ideas and their relationship to social and political developments. Now, this project had no aspirations of making any connections with the present; it aimed in mapping the intellectual trends from the fourteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, seeing them in the background of previous Islamic thought, rather than modern ideas. There has been a lively discussion about “Ottoman Enlightenment”, indeed, or if you prefer an “Islamic Enlightenment” of the eighteenth century. This has less to do with political ideas than with a democratization of knowledge and a legitimization of individual thought, which in my view was linked somehow paradoxically with the influential fundamentalist movement of the seventeenth century, the Kadızadelis. Indeed, if Islamic fundamentalism is a recurrent idea in modern political realities it has its origins in the Ottoman era. But in my view it is more interesting to examine certain political developments of the eighteenth century, namely the self-legitimization of the janissary networks seeing themselves as representatives of all Muslims and thus legitimate members of the political nation (the community which could claim a share in political deliberation). It can be said that the Ottomans had their own share in the “Age of Revolutions”, although a very sui generis one, and that the internal dynamics of Ottoman society were less “despotic” than we usually tend to think.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Greek News Agenda:

- Restoration of Ottoman monuments in Greece

- Remembering the Ottoman Past

- Antonis Hadjikyriacou on the Ottoman period, the Greek Revolution of 1821, and new paths in Greek historiography

TAGS: MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES | MODERN GREEK HISTORY | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | OTTOMAN PAST | OTTOMAN STUDIES | RESEARCH