A new literary magazine, “To Parasito” (The Parasite) dedicated to the practice of literary translation and the various journeys literary forms can take was recently launched by Nissos Publications. Its editorial team consists of both writers and translators, that is Marina Agathangelidou, Panagiotis Arvanitis, Giorgos Giovanidis, Krystalli Glyniadaki, Anna Griva, Efstathia Dimou and Eftychia Panayiotou.

Cover design by George Triantafyllakos

Reading Greece* spoke to The Parasite’s editorial team about the scope and contents of the first issue, the transformative relationship between “poetry and the parasite of translation”, translation as an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value, and the crucial role of translators as mediators between different languages and cultures.

“To Parasito” is a new literary translation magazine, a magazine dedicated exclusively to the translation of literary works (poems, short stories and essays). What’s the story behind this venture of yours? What about its title?

“To Parasito” (The Parasite) is a new, biannual literary magazine dedicated to the practice of literary translation, to translators themselves, to the channels of communication and the intersections between different languages, and to the various journeys literary forms can take. We began discussing the idea about a year ago and wouldn’t have succeeded in bringing it to fruition without the unreserved support of Nissos Publications. As an editorial team, we thought it was appropriate, perhaps necessary, to create a fresh and welcoming space for highlighting contemporary international literature. And, given that the role of the translator has become more important and more visible in Greece in recent years as a new generation of translators is graduating to the forefront of the profession, foreign translations have become increasingly important for the domestic book industry. So we’re trying to create a dedicated meeting place where new, or even older, translating voices can present their own interesting suggestions in the field of translated poetry, short stories, and essays.

Now, when it comes to the title: as mentioned in the editorial note, we’re referencing Michel Serres’ landmark theory of communication in Le Parasite, where “the parasite” can become the protagonist of public dialogue through interference, noise-making, and beneficial contagion. By transplanting Serres’ idea to the core of the function of translation, we wanted to emphasize the principal role translation plays within world literature: there are no “perfect” original works, nor “imperfect” translations out there; there’s a grand Host (world literature itself) and the various Parasites representing ethnic literatures that both feed on and nourish back the Host, both linguistically and semantically. Despite the negative connotations the word may have in current discourse, as a metaphor for translation it’s not to be understood as a loss of meaning or as a freeloading practice on the original text. The opposite, rather: it is the noisy communication of journey-making, cultural exchanges and confluence.

As we read in the editorial note, the magazine “intends to (re)introduce us to writers and texts from all over the world, mainly focusing on contemporary literature, on the literary present, while also looking back to the short twentieth century”. Tell us a few things about the scope and contents of this first issue.

Our aim, indeed, is to present to the Greek-reading public contemporary voices of world literature, writers who have not really been translated into Greek before – but without excluding older or established writers. The very first issue is dedicated to “Poetry and the parasite of translation”, which harks back to the title of the magazine of course, and the concept of translation as a “parasitic” process, but focuses clearly on poems written about translation and translators. So one can find therein, for example, a poem by the Italian poet and translator Valerio Magrelli together with an interview where he speaks with great shrewdness on the crucial dual identity of the poet-translator. Then there’s a series of translated poems from America (by Adrienne Rich, Tess Gallagher, Yusef Komunyakaa, Rita Dove, Charles Simic, Billy Collins, Elaine Equi, Charles Wright, Idra Novey, and John Freeman), as well as poems by Cristina Peri Rossi, Uljana Wolf, and Yasmine Seale. Beyond this specific theme, one can read poems by Fanny Howe, an excerpt from the larger poetic synthesis entitled Advice from 1 Disciple of Marx to 1 Heidegger Fanatic by the Mexican poet Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, literary companion to Roberto Bolaño, as well as short stories by Adelheid Duvanel and Juan Rodolfo Wilcock.

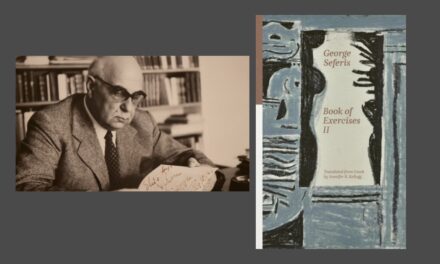

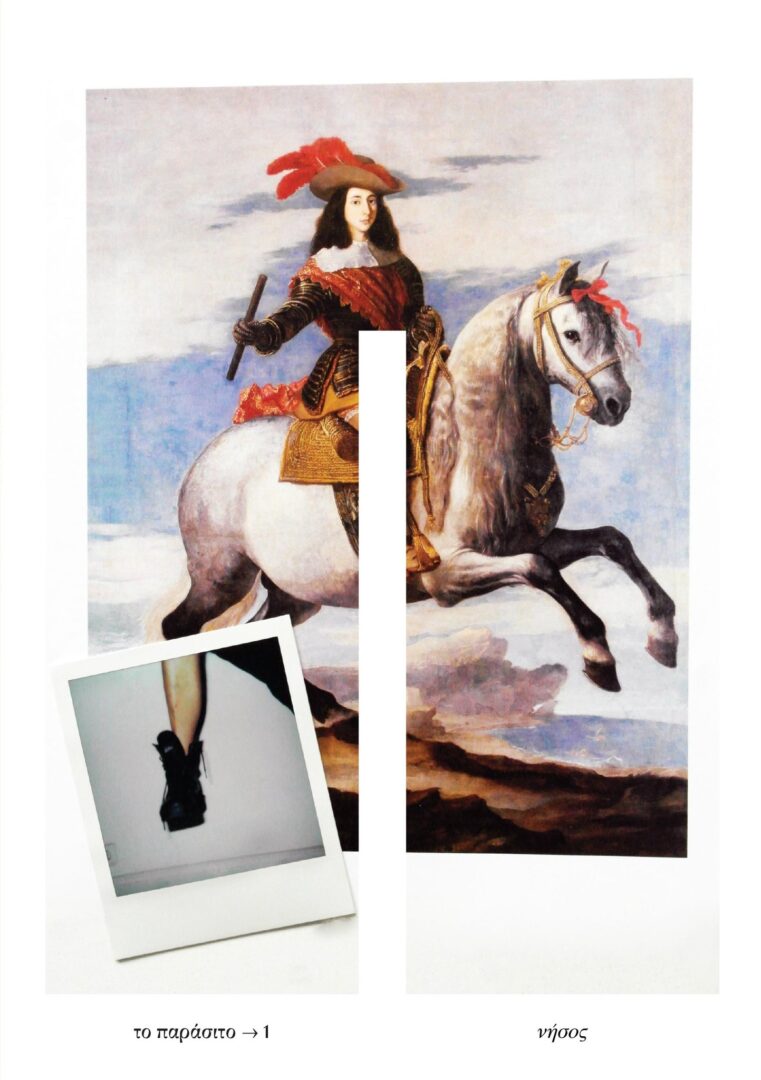

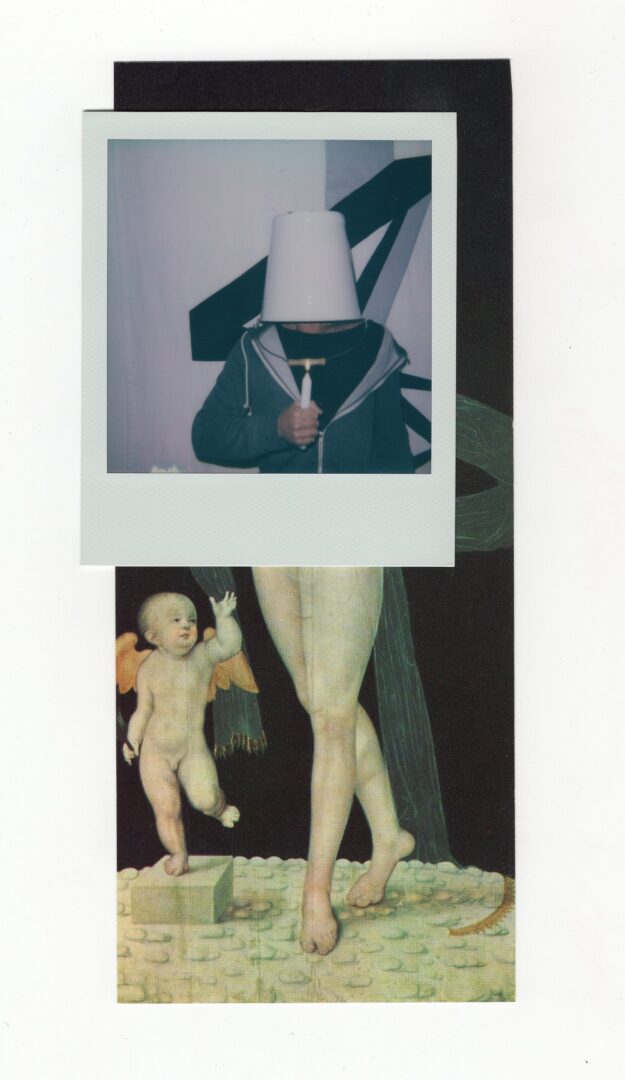

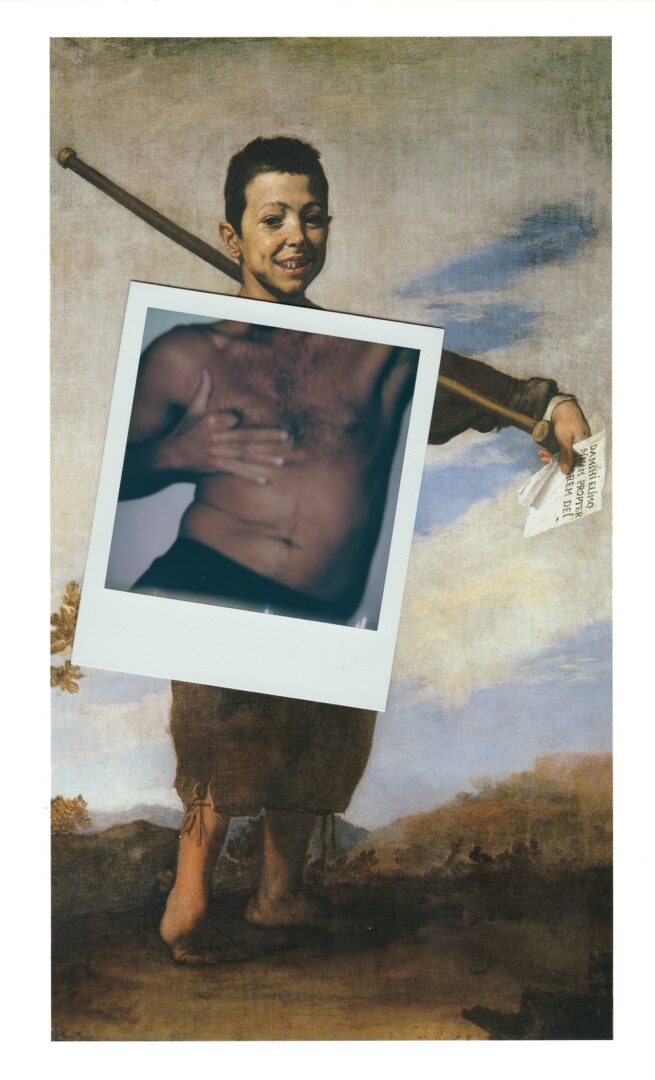

In the essay section there’s a small excerpt from Borderlands/La Frontera, a book by Gloria Anzaldúa, as well as an essay by the German translator Esther Kinsky, and a mini essayistic memoir by the British writer Ned Beauman. And because we have founded this magazine as a translators’ meeting place, we’re aiming to interview at least one translator per issue – and in this first issue, we’re talking to Jan Henrik Swahn, who is the Swedish translator of the Nobel laurate Olga Tokarczuk. A small critical section in the end presents reviews of translated books, whilst we’ve reserved a special place for the aesthetics of the magazine by calling upon a visual artist to contribute original work for every new issue: their work appears on the cover of the magazine, as well as in a “gallery” at the end. For the first issue, we’ve had the honour to be entrusted with 7 collages by the Berlin-based visual and performance artist Yiannis Pappas.

Lucas Kranach, Secchio e Amore 1540-2024/ © Yiannis Pappas

Could you elaborate on this transformative relationship between “poetry and the parasite of translation”? Does translation constitute both an interpretative means and a poetic metaphor?

Translation is obviously a means of interpretation; and yes, it can equally be a means of metaphor. But let’s put this another way: moving actual furniture from one place to another can be a wonderful metaphor for translation. So says Valerio Magrelli’s poem included in the first issue: moving places, packing, unpacking, relocating (foreign) words about as objects.

Now, is this relocation of words a poetic, a creative, and perhaps even a transformative experience? Without doubt. But translation is not just that, given how poetic discourse can speak about the practice of translation. And this can be seen in the poems that fall under the first issue’s special theme: they reflect the very act of translation itself; they explain how poetry “freeloads” on translation and vice-versa. Their subject ranges from the linguistic, emotional, and reading challenges faced by translators to their political and personal implications. Other poems salute translators as a troop of meticulous readers and interpreters who can navigate linguistic and semantic complexities; and as carriers of words that can cross cultural and temporal boundaries, influencing the reception and interpretation of original texts.

So “poetry and the parasite on translation” focuses on how poetry and translation meet; on poetry as a parasite that transforms and is transformed by the original text; and on the means by which translation –by making noise– can lead to new interpretations. This “noise” can thus be considered a type of interpretation in itself, where the translator’s choices and the cultural context in which they operate influence the way in which the original text is rendered in the target language. A parasite, after all, is a metaphor for how the original text can relate to its translated versions. And as a parasite depends on their host to survive and simultaneously transforms that host, in a mutualist interaction, so does a translation depend on a host original, in a mutualist interaction that transforms them both.

Would you agree that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value?

Absolutely. First and foremost because a translation can be good, and it can be bad –as in accomplished or not– and so it demands an evaluation on its own right, rather than solely as a means to another work of art. It is also subject to rules and assessments that are tied to the target –rather than the original– language, and so creates an entirely different space for understanding and critique within that language, a space that did not previously exist without it. Transcriptions of symphonic pieces for piano obviously demand appraisal on their own artistic and aesthetic terms; often, they can be even more appealing than the original. Translations are like that too: if they’re good, they can replicate the exaltation the original text produces in the original language; if they’re bad, they condemn even the best of texts to boredom and confusion. It’s hard to think of a more surgically important act than that.

Jusepe de Ribera, Der Junge mit dem Loch im Brustkorb 1642-2024/ © Yiannis Pappas

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

We fully agree with this view. Especially when it comes to literature, what’s crucial is not only what a text says, but how it is said. The identity of a text is constituted by the relevance and interplay of form and content, and should be thus kept intact when the text is transferred into another language. The translator, therefore, is called upon, first and foremost, to be a trained and attentive reader: to identify the stylistic elements of a text (e.g. irony, ambiguity, plain or restrained expression, humor, word games), its linguistic peculiarities and its various linguistic levels, to feel the musicality, rhythm, and pulse of the language, and to understand the ways in which all of the above interact with the content. Furthermore, they are called upon to reproduce these elements in another language, which inherently functions differently from the original language, which means that the translator must find solutions, be inventive, take liberties, so as to convey not just the meanings of a text but its particular character, its distinct identity. Now, failure to meet such a requirement, given the responsibility and risk involved, does not automatically mean that one’s translation will be unethical (which is a heavy word, as it suggests an intention); but it is very likely to be inadequate.

What is to be expected from the magazine in the issues to follow?

The contents of the next issue are already assembled to a satisfactory degree. There will again be translations of poetry, literary prose, and essays published for the first time in Greek, as well as original interviews conducted with Greek and foreign translators, critical presentations of translated books, and the work of a cover-gracing artist. But we are particularly interested in and excited by the special theme of issue 2: poems and essays relating to what self-identifies as “poetry of disability” and is theoretically often referred to as disability poetics – poems that not only thematize the experience of disability, but also reclaim the gaze on its behalf, by subverting eons of stigmatization, marginalization and oppression, and by restoring what is marginal, derided, and invisible to the forefront.

In general, we’re hoping that our future issues will be numerous and flourishing, that they will become a welcoming presence in Greek publishing, and that they will manage to establish a meeting point for interesting interactions between writers and poets, fortuitous collaborations between new and more experienced translators, and a fecund field for discussions on the art of translation.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE