Born in Athens in 1952, Veroniki Dalakoura is considered one of the leading Greek poets of her generation. Her writing shows the influence of surrealism and her books often combine verse poems, prose poems, hybrid forms, and longer narratives in provocative ways. Her books Holder’s Painting and 26 Poems were finalists respectively for the Greek National Prize in Prose and the National Prize in Poetry. Dalakoura is active as a literary critic, reviewing books in the leading Greek newspapers, and has translated Spanish, English-language, and especially classic French writers and poets into Greek: Rimbaud, Flaubert, Stendhal, Balzac, Baudelaire, Desnos. She lives in Athens.

Since your first book in 1972 till today, more than fifty years later, what has changεd and what has remained the same in your writing? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

Simple as it may seem, it is really a difficult question. Time is immovable, we are the ones that move within it. Is it possible that my view of the world has not changed in more than 50 years? And again, is it possible that my psyche has been so transformed that my references to events and experiences have become so different, so that the result, in this case writing, bears no relation to what was captured at the time? Remember, you are talking to someone who does not believe in free will. Any changes are merely aesthetic in form.

Surrealism combined with symbolism in the first books; hermeticism in the later ones, because progressively there was a strong desire to hide. Of course, we must not overlook the various readings, the discovery of new sources of inspiration and the attempt to be me without revealing the persons who, through love or friendship, without altering the core of my being, have had a decisive influence on who I am. It was through this process of being that adulthood followed youth, and maturity will meet old age. As points of reference in these endeavors, because that is how I see my poems, there is memory, regardless of whether only a few minutes or an excessively long time elapsed from that something that prompted me to write, to capture it (very selfishly for me first and then for the reader).

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

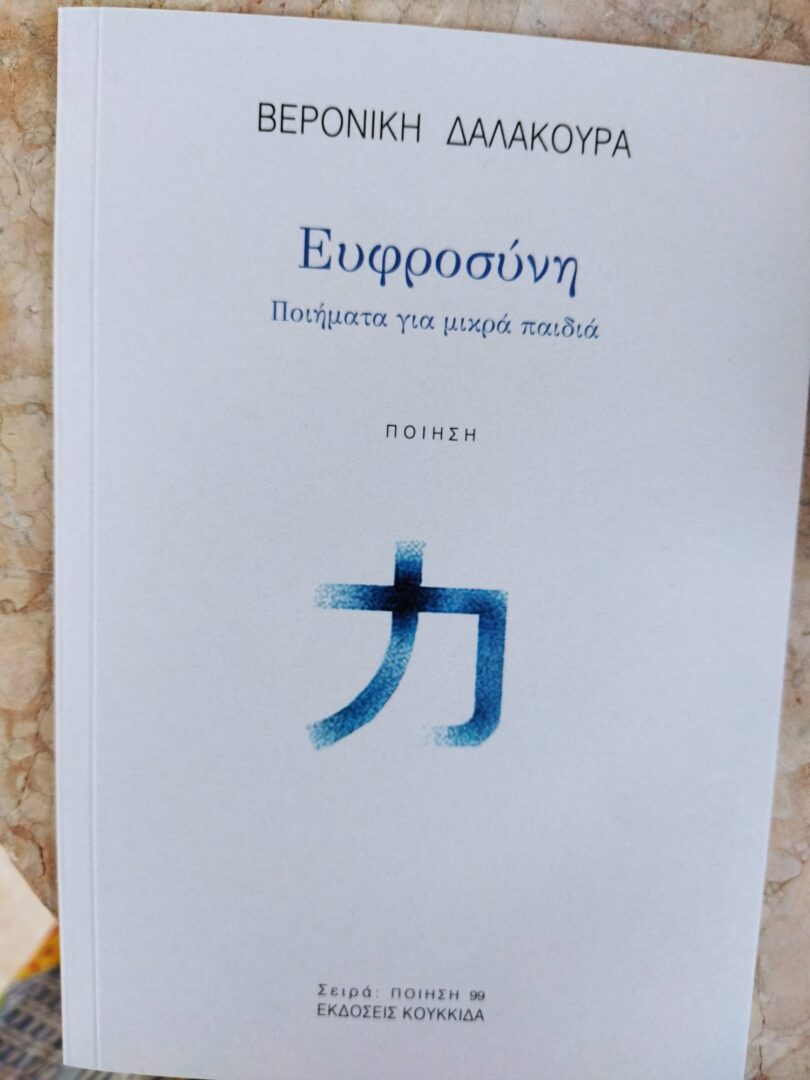

What do we actually mean by “language”? If we refer to writing in good Greek, perhaps I have failed since I am not direct and “understandable”. If we mean the way, the formula, I’m always experimenting. My latest writing venture, Euphrosyne – Poems for Young Children (Koukkida 2024) is about a name, a principal name, of a beloved creature, my niece whom I lost tragically. Our children are not only the ones born of our bodies. I am fortunate enough to have a daughter, whose name Leto refers not only to a mythological deity, but also to stone, a solid, strong material. Euphrosyne, in contrast to her name, which means joy, a feeling of cheerfulness, joyfulness, proved by her painful existence that language is nothing but a game, the sparkle to create a universe that is in itself perishable and corruptive. We certainly have a lot to learn from such experiences, yet learning is not always about knowledge: we rarely come close to the latter; this usually happens towards the end of earthly life.

And to forestall your well-intentioned next question, let me refer to my own stance: although I often swear, especially through writing where boldness is taken as a challenge, this is but the expression of my heretical and perhaps blasphemous side: yes, I am a believer. The approach of universal faith and pain weighs on all living things; the book was written not only for her, E[e]uphrosyne, but also for her parents, her siblings, especially my brother who lived through the fatal fall. James, brother James, was not a disciple of Jesus, yet it was to him that He first appeared after the Resurrection. The cryptic word of the Gospels demonstrates, centuries before epistemology attempted to interpret everything, the multiple forms of biological existence. Even though Euphrosyne no longer exists as a body that we can touch, it demarcates the “euprhosyne” between the future and the present moment of suffering. Poems for Young Children, for this is the full title of the short collection, suggests how inarticulate speech can become when uttered breathlessly in a space of secrecy.

So, what is the meaning of language when it comes to loss? The Mystics (of the East) touched it with near perfection. Western people struggle to exist through what they have not been taught to express with as much simplicity and clarity as possible. So that is why I characterize my poems and what I write in general as “endeavors”. And this struggle, at least as far as poetry is concerned, has come to an end for me.

Poetry, prose, translations, teaching, academic research. Where do all these attributes meet? Which do you consider to be the binding thread?

Let me give you the short version: poetry – prose since the age of fourteen, translation since my twenties (many remain unpublished), teaching (how I hate the word) much later. Technical Vocational School of Kalymnos, Agia Varvara Highschool in Egaleo, Adults’ Schools in the last years: where I keep learning together with my apprentices. The fact that I was not a philologist helped me to approach everything through literature, especially poetry. I consider it a great gift – at least for me. In my free time I do research about refugees, mainly from Pontus. Now, in the hope that time will be kind to me, I am finishing a short study – about the size of the man I have been studying for years – Ioannis Sykoutris.

Through a part of his vast oeuvre, specific articles, studies and journeys, such as that of Cyprus, and the coincidences of space and time, I am trying to unravel what has so far remained obscure. I fear that any simplification, when it comes to Sykoutris, leads nowhere. His regressions were not the result of embarrassment, but rather of a struggle, a condensation beyond the human. Only those who knew him personally, and I was fortunate enough to meet several of them, could give an interpretation regarding his – at first sight – politically extreme views, which – note this – were not life choices. The rest will never be answered. Dimitris Dimopoulos, of KOYKKIDA Publications, was brave enough to accept this little book which, selectively of course, offers some insight into the Deadlocks of the Interwar Period, as the subtitle of the book will be.

In an interview to Michel Fais, you said that “you believe in this invisible bond. The book is the mediator and also the way for readers to bond with each other”. Which writers and books influenced your own writings? How is this influence imprinted in your books?

Thanks to Michel, I had the opportunity, as with this interview, to talk about books in general, but also about my own library. In addition to those that, collected over the years, have been standing lastingly next to me, there are others, many I would say, which I decided at a certain moment to give away. And not only books, but also rare manuscripts of rare people. And this, without expecting any return or even recognition: it is enough for me, as in every gesture, to feel appreciation through this little gift. Of course, there are exceptions, people who, appreciating not the “gift” but the feeling, the love it expresses, the intention of an invisible and strong bond, have stood by my side in very difficult moments.

I should mention my colleague from Agia Varvara Highschool, the mathematician and collector Iordanis Christodoulou, to whom I donated most of my correspondence: letters from Stratis Doukas, Miltos Sachtouris, Nikos-Gavriil Pentzikis, Nikos Engonopoulos, Giorgos Savvidis, Takis Sinopoulos, Nikos Spanias, Michalis Katsaros, Giorgos Chronas and many others, including letters of a very personal nature. And I keep on giving! I am not forgetting my young, dear friend poet Yannis Vitsaras, our Yannos, as he was called by our much lamented friend from my teenage years, Haris Megalynos. Yannis, an important poet also, deserves letters, and notes from poet friends of my generation. And books with dedications! This bond, even if it is not my own books, is a photo-illustration of a period of time that is slowly coming, as far as our walk through it is concerned, to its natural end. Perfectly natural. So, let us offer it to the younger ones.

Don’t ask me about my influences; I’m having a hard time, I can’t lie. I was mainly influenced by foreign poets and writers. With the exception of the writers of the interwar period; I owe my knowledge of them, apart from Karyotakis of course and Giorgos Sarantaris, whom I read as a child, exclusively to a special person, thanks to whom I loved Anastasios Drivas, Mitsos Papanikolaou and so many others. I was late to meet the extraordinary Melissanthi. And belatedly I admired Victoria Theodorou, our later close friend; and I am glad when young people discover them earlier than I did.

What about the new generation of Greek prose writers and poets? Do you have the potential to move beyond national borders and have their voice heard more broadly?

I cannot keep up with the number of new books that are being published. Whatever comes into my hands, believe me, I read it carefully. However, if I mention some names I would be doing an injustice to a young poet or poetess – because there are many more young women writing – since I am not familiar with the work of the others. Considering the fact, a stark reality of our days, that if a writer/poet passes away and does not leave behind a strong group of admirers – supporters of his/her work, he/she is forgotten. So, allow me some exceptions: the wonderful poems of Niki-Revekka Papageorgiou (1948-2000), such as Του λιναριού τα πάθη – Ο μέγας μυρμηκοφάγος [Agra Publications] and the only book οf Penelope Syrmakezi (1949?- 1994) Πρώτη Χρονιά στο Νηπιαγωγείο with poems written in the 1970s and published by her in 1989. Also, the books, those that are now in Diogenis, by Kostas and Petros Kouloufakos, Ioannis Leontakianakos (1954-1974); the work of the unforgettable, legendary Takis Pavlostathis (1943-1999) [Nefeli, 2006] and of course the poems of his dear friend Haris Megalynos (1951-2024) whose poetry, our endless discussions about it and the questions that plagued our youth, had a decisive influence on my own first writing attempts.

A comment: in following, as far as possible, original works and/or translations of contemporary foreign poets, I find a common path with our own 21st century poets; a tendency to internalize emotions leading to an “explosion” whose materials, however, are as cheap and overused as fireworks. An approach, but only external, to elements that have nothing to do with modernism as we experienced it and as it, with all the weight and essence of the word, was and still is. And yet a love for nature and for what we seem to be losing. I am not a literary theorist or a critic, to say more.

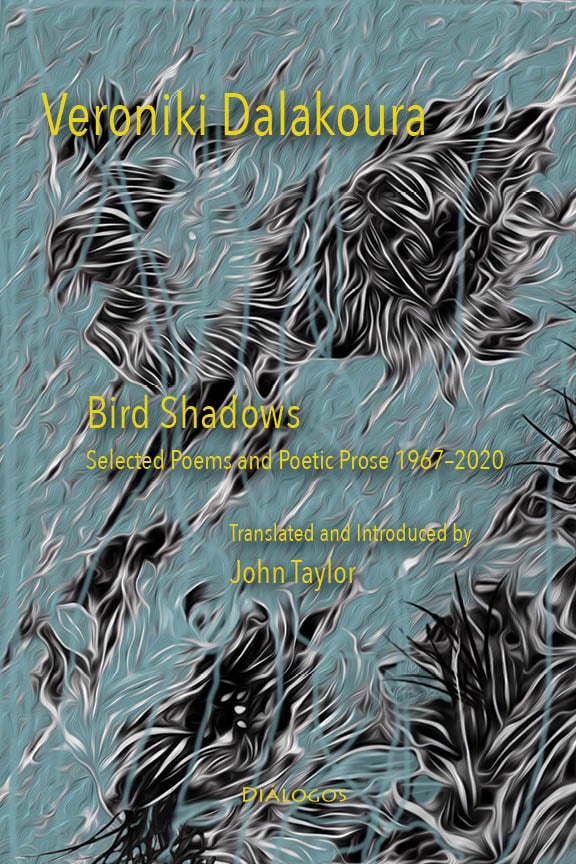

I have been fortunate to have my poems translated into English, after many years of work, by the poet, writer and critic John Taylor. It remains for me to wish, in all sincerity, that in these strange times when a return to – in the broadest sense – tradition (I clarify: of movements) is seen as one of the greatest defects of poetry, even of the poetic text that was once the springboard for the truly modern, they will, sooner or later, be equally lucky.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read also: Book of the Month: “Bird Shadows: Selected Poetry and Poetic Prose 1967-2020” by Veroniki Dalakoura

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE