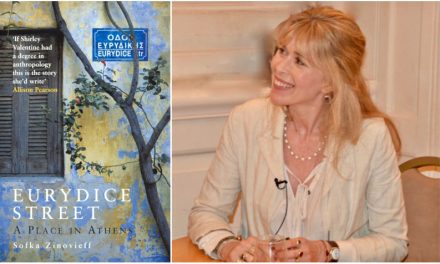

Nadi Chatzigeorgiou grew up in Syros Island, Greece. She studied Philosophy and then German Language and Literature at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. She steadily studies anthropology, music and dance. Her first poetry book ήδη προς εξαφάνιση (Thines, 2022) has been awarded with the “Anagnostis” Literary Prize for New Poets (2023). Writings and drawings of hers have been published in print and online magazines.

Your first writing venture ήδη προς εξαφάνιση (already about to go extinct) (Τhines, 2022) received the “Anagnostis” Literary Prize for New Poets (2023). Tell us a few things about the book.

This is my first poetry collection which I have been working on for about ten years, guided by that sentence which eventually became the title, already about to go extinct, which is untranslatable, since you lose the double entendre: in the original Greek “already” and “species” sound exactly the same.

It is a book made of creatures with wings, with roots, or creatures aquatic, creatures that appear fleetingly and escape the world of transactions. During their brief lives, they wander wantonly, they seek questions, they build bridges.

The book opens with the “fisherman” and ends with the “hunter,” as perpetual human conditions. Both of them are tragic figures, since they face a dilemma of life and death. By answering the dilemma, they show us how one can be saved by saving something.

Τenderness, innocence, empathy, and a strong underlying sense of justice seem to be among the main traits of the poems. Where does the personal meet the political in your poetry? Is tenderness another way to talk about broader social concerns?

The individual cannot be separated by their social and political context. This is what shapes them, this is what they partner with, and this is what they resist.

Remaining innocent and gentle while faced with the world’s cruelties is a difficult mission, a mission that we can fail at any time. But at the same time, it is also a political stance.

I am not talking about an utterly individualistic redemption devoid of political aspirations, struggles, or ruptures. In our day and age, the logic of a personal identity and of an individual happiness as an end in itself, is a fantasy that we pay for with terrifying levels of inequality, poverty, and savagery.

“… what if we had / noble sentiments/ and had to / against our very nature/ turn our weapons/ on the enemy,” as the poem says.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Contrary to other arts, which demand the use of specialized tools and implements, poetry is created with a tool that everyone knows how to use: language. What many, though, may not realize, is that poetry is as universal as language. Because of the nature of language, the poetic is constantly on the tongue of people, albeit not always consciously. The work of those who write is a more systematic approach to this human tendency for the poetic game, placed on the page.

No matter how important the content of poetry, poems are written with words. They are perceived as such, because of the special way with which they express things that have been written dozens of times in the past. Poems have verses, to which one returns, like the way that one returns to songs or the favorite lines from a movie. One often says, “I don’t remember precisely the line, I shouldn’t say it and spoil it,” and consults the book again.

For me this is a good poem, this is how I treat it and this is the way that I’d want my language to affect people.

In his review of the book, Argyris Dourvas highlights some political aspects of ecology in your book. How does the book delve into the relationship with the natural environment? Is this relationship a political relationship par excellence?

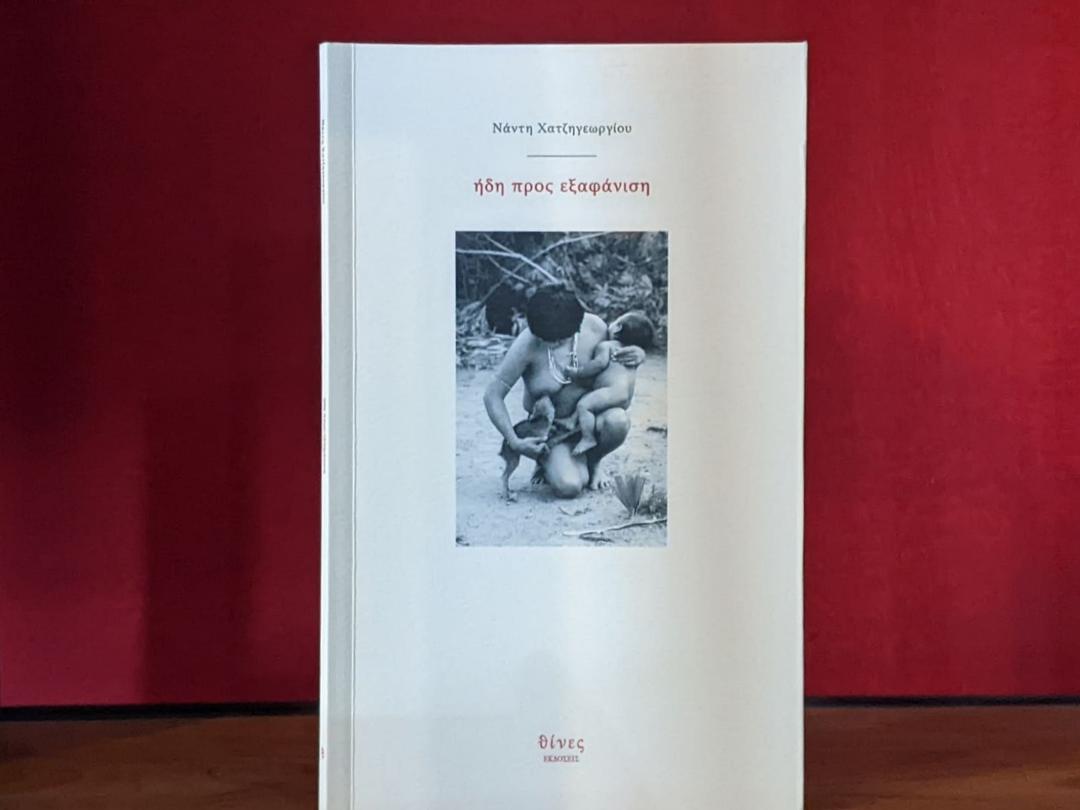

In his review, Argyris Dourvas roots out, correctly, many of my hidden references. The book was written during a period when I was studying anthropological texts. I read about the potlatch, about the nature of the gift, and the construction of canoes in Melanesia. I read about the tribes of the Amazon, where women give suck to wild animals, or for tribes in Indonesia who live on water and walk on the seabed as if it was land. It is certain that these ethnographic studies influenced the way I perceive the world, and consequently, my writing.

That’s how I chose the photograph on the cover of the book, which was taken in 1992 by Pisco del Gaiso in the Brazilian Amazon. It was him that graciously gave me permission to use it, after he confirmed what I had read. A woman from the tribe of Awá Guajá is nursing her baby, while at the same time nursing a baby boar with her other breast. The women of the tribe routinely nurse wild animals whose parents have been killed by the hunters. These animals are considered members of the family and are never slaughtered for food.

I consider this a profound example of coexistence and cooperation. You eat the meat, you give the milk, you become for a while the parent that you have taken away. This cruelty coupled with care seems to contain the many contradictions of the human condition. In the world of streamlined industrial rapacity, hypertourism, and the exploitation of man and nature alike, such a thing seems completely unheard of, if not something out of a saccharine postcard.

I tried, as much as I could, to avoid exoticism and the Enlightenment idea of the “noble savage,” which probably accompanies the narrative of a person who writes in Greece in 2024 about such a distant reality. I know for a fact that gestures such the one in the image, gestures that break the vicious circle of progressive destruction, can be found much closer than the ends of the earth.

More generally, how does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Every person occupies two places at the same time. The one they are living in and the one they imagine. In what place is someone when they are listening to music, when they are peeling potatoes, or when they are sleeping?

Literature is a way to enter through the use of imagination into a world that someone else has created for you. Seen this way, if its creator wishes it so, the literary world can be a radically different world than the real one.

Such a literary world, as all utopias, moves along this spectrum: it can serve as a call to overthrow the real or as a passive escape from it.

How are young writers related to the global literary trends? Where does the local and the national intersect with the international and the universal?

We are living in a country with an old and tried language, but at the same time a “small” one. Very few Greek writers are translated abroad, since they are is no state cultural policy on this front. These writers have access to the books that get translated into Greek. At the same time, they read much in the original, especially in English, something that at times means that they have a limited exposure to different linguistic and cultural environments.

Compared to the previous century, the internet and the great number of translations into Greek have brought about major changes. Today we have access to texts that up to relatively recently we couldn’t even dream of reading, something which has proved decisive for contemporary literature. Therefore, it could be said that some Greek translators have been more influential to Greek poets or writers than the latters’ colleagues.

Furthermore, literary festivals and residencies provide a way to meet young writers from all over the world. Sadly, they are few and far between, with many requirements and therefore exclusions. The state cultural policy is lacking, something which can be inferred by the fact that working as writer in Greece is not considered a proper profession, and it is difficult to practice as such.

In closing, I believe that every language carries in itself something of human experience in a way, let’s say, universal. Even when things are lost in translation, what remains may concern us personally, as if it was written for us or for the person next door. The important thing is for the text to reach us. Unfortunately, this is dictated by the laws of the market and promotion, which means that many texts that concern us will never reach us.

Luck and the writer’s tenacity often disprove this fate.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

**Translated from Greek into English by Panagiotis Kechagias

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE