Sotiris Souliotis (winner of Greek State Award for Translation of a Work of Foreign Literature into the Greek Language for 2023-the novel The other name of the Norwegian Nobel Prize Winner Jon Fosse) is a Greek- Danish translator, born in 1971. He studied Greek Philology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, translation studies at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark), and is now completing a Master degree in “Politics, Language and Intercultural Communication” in the Ionian University in Corfu.

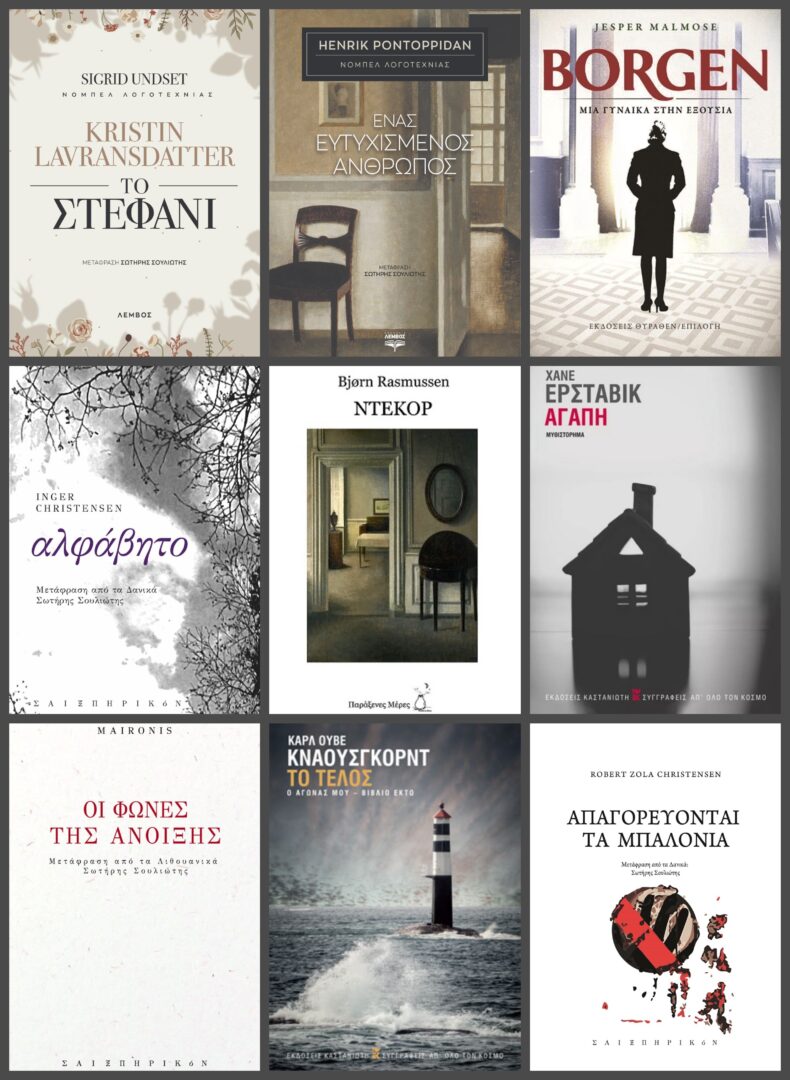

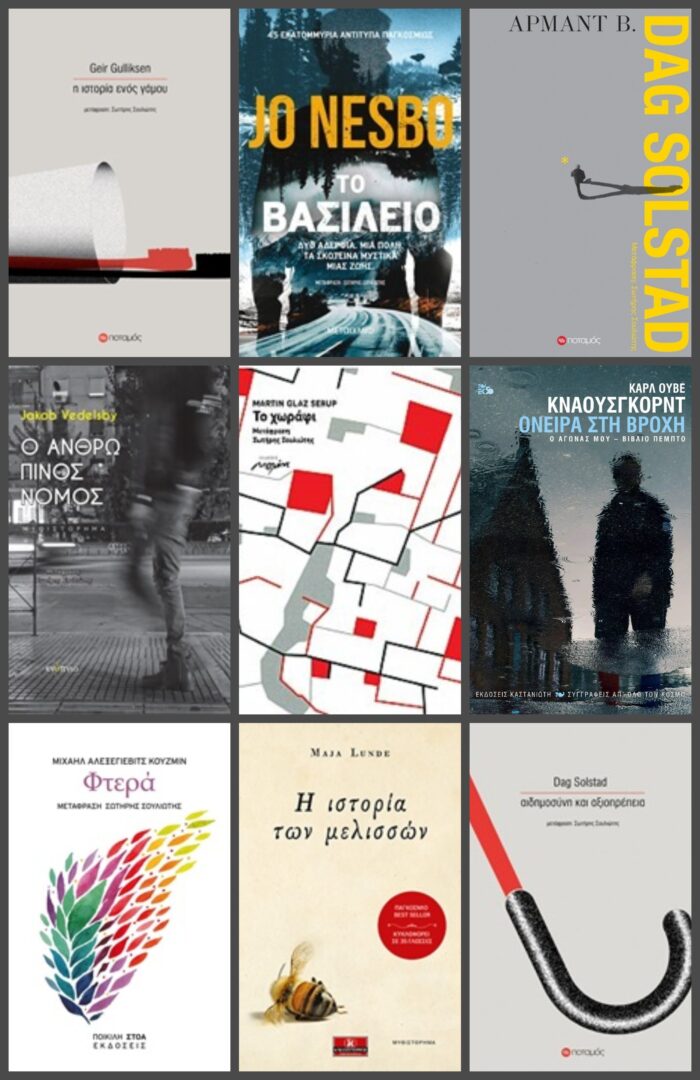

He translates Scandinavian and Baltic literature into Greek, as well as Greek literature into Danish. He speaks 10 languages and has translated more than 70 literary works (both poetry and prose) from Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Lithuanian and Russian into Greek and from Greek into Danish.

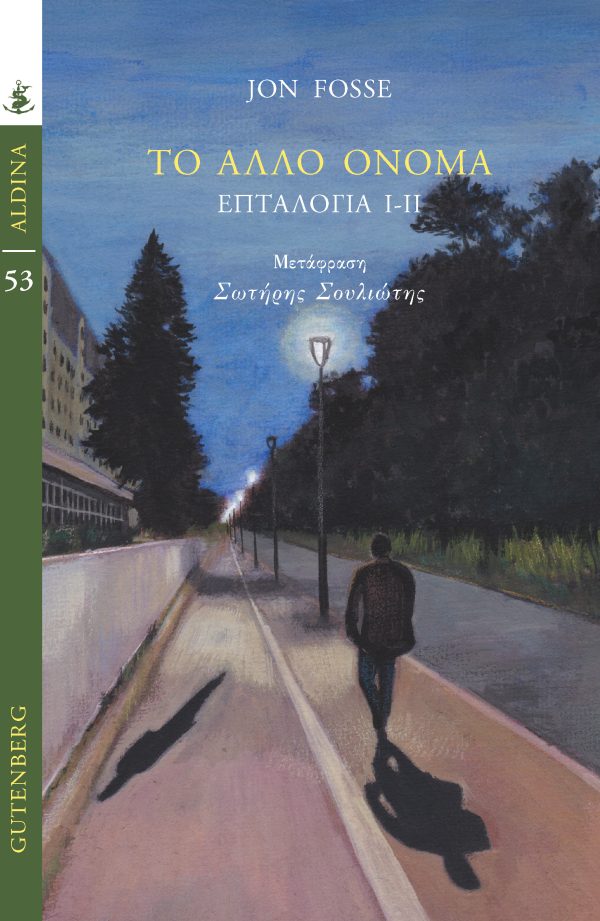

Your translation of The Other Name by Jon Fosse was awarded the Greek State Award for Translation of a Work of Foreign Literature into the Greek Language with the (2023). Tell us a few things about the book and the major challenges you were faced with while translating it.

When I started the translation of The Other Name, published in Greece in 2022, I had no idea that Jon Fosse was going to win the Nobel Prize, just that he was a great Norwegian writer, who until now in Greece was known mainly for his theatre plays, and therefore his prose was practically unknown to the Greek readers. The hero of this novel, the widowed painter Asle, lives in an isolated village in Norway and is about to hold an exhibition in a gallery in Bergen, where he often exhibited. Also involved in the story is his namesake and friend, another Asle, who is also a painter, but lives alone and is an alcoholic. The lives of the two Asles become intertwined to the point where one often wonders if they are one person or two. All this is described in a slow, dreamlike atmosphere, with first-person narration with almost no punctuation, with daily elliptical dialogue and phrases, against the background of the frozen Norway, snow, the raging sea, stories from the past of both Asles, with the persons that surround them, the questions about life and God, and all this in a world that could be today, but maybe not, as neither mobile phones nor internet are mentioned.

The main challenge I had with this book was that the language it was written in was Neo-Norwegian, i.e. Nynorsk, the second official language of Norway. The first is Bokmål, the language created from the time of Danish colonialism in Norway and in the written part is closer to Danish. Neo-Norwegian is more ancient, more poetic and closer to Icelandic and the Old Norse languages, it often has other words, different grammar (i.e. three genders instead of two) and other means of expression. But I easily got into its spirit and the spirit of the author and the translation flowed without problems, since Fosse’s speech is at first sight simple and everyday, the translator just has to have his emotional antennae open, and catch the mood of the author’s characters. It happens in every translation, but in The other Name and the other books in Fosse’s Septology, which I have also translated and will be published soon, it is more pronounced, as it is essentially about an old man of the North who lives alone with his memories.

How did your professional involvement with literary translation begin? What about your interest in Scandinavian literature?

The translations of Scandinavian books for me started in 1996. My first book was the Danish Peter Høeg’s novel The Borderliners (published by Psychogios Publications), at a time when there were neither computers nor Internet. I had written all the translation by hand and had it computerized on a photocopy shop. These were the conditions at that time for all translators, more or less. But I have to say that this story started earlier, in 1992, when I went to Denmark with an Erasmus exchange student program and learned the Danish language, living there for a year. Since then I had done some other translations from Danish, but most translations came after 2001, when I had already moved to Denmark and was now living there, where I lived most of my adult life, around 20 years.

It was the time when the Greek public had begun to be interested in Scandinavian literature, not only Danish, but also Norwegian and Swedish. And since if you know one Scandinavian language (in my case Danish, which I speak as my mother tongue), you can also cope well with the other ones (i.e. Norwegian and Swedish), I translated many works from Norwegian as well. Of course, I also had to immerse myself in Norwegian, as it differs from Danish in many ways and stylistically (as these are completely different cultures: Denmark is a lowland country, while Norway is mountainous, with several similarities to Greece, despite the climate difference). But my countless trips to Norway and my contact with Norwegian writers and non-writers helped me a lot in this.

My own interest in Nordic literature began because I had always been drawn to this region of the world, ever since I was 14 years old, when I would see these then-unknown languages in machine manuals alongside other languages, and tried to decipher them, without help, which I finally did, before I became adult, reason unknown. If you are interested in a place in general, it goes without saying that you are also interested in its literature. However, Nordic literature in itself is very interesting, because it talks about many aspects of modern life, is often globally oriented, while at the same time is unfolded in the local contexts of the North, and has social sensitivities.

What is that makes Scandinavian literature attractive to Greek readers? And, in turn, does Greek literature has the potential to attract the interest of a Scandinavian audience?

Nordic literature started to become attractive to the Greek readers around the early 2000s, when Greeks began to turn their gaze to the Nordic societies and the Nordic welfare states. The Greek reader became curious to know how these people thought and wrote, who created such organized and prosperous societies. A Scandinavian literary work was a journey through these countries, even if it was a mental one. In this way the Greek readers tried to understand Scandinavia of the welfare state, harmony and prosperity. The effort of this understanding continues until now, even though the mood for understanding has somehow softened due to the difficult economic and social conditions in which Greeks live: “What are we trying to understand, since these things cannot happen here in Greece?”.

On the other hand, Greek literature was known in Scandinavia from the time of the Junta, when thousands of Greeks sought refuge in Scandinavia (mainly in Sweden) as political refugees. Poets such as Yiannis Ritsos, Mikis Theodorakis, but also writers such as Antonis Samarakis, Konstantinos Theotokis and others had been translated into Danish. The Nordic audience was interested in knowing who this people was, tormented by dictatorships, wars and other political situations, often relying only on their own hands to move forward. But for a while this course of Greek literature in Scandinavia was left in the middle, as for many years there was no official Greek state body to promote Greek literature abroad, like before the Financial Crisis the Phrasis program (which was abolished during the Financial Crisis) and now Greeklit. Such institutions exist in almost all countries (in Scandinavia they work perfectly) and help a lot in promoting their country’s literature abroad.

However, I have to say that during the Financial Crisis, despite the lack of a Greek state body subsidizing Greek literature, several Greek writers were published, at least in Denmark, such as Nanos Valaoritis, Dimitris Dimitriadis, Christos Oikonomou and others. So this shows that the Danish public was thirsty to know about modern Greece and the Greeks, defying the dominant ideology of the media, who wanted the Greeks to be “lazy”, “spoiled”, “who only know how to ask for money from Europe” etc. An echo of this era is also the publication of Titos Patrikios in Denmark, translated by me into Danish, which will take place in November 2024. Although it is subsidized by Greeklit, the desire of the Danes for it existed before.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

To a point, those who believe this are right: each book is governed by the language that surrounds and composes it. But ONLY to a point. This is because often the reality is similar, or close, despite the language differences, or, even if it is not, the emotional states of the heroes of a work or the authors, it is something, one might say, universal. And this is where the role of the translator lies: to decipher the moods, thoughts, feelings of the characters in a book, to depict the reality of the book in a way that is emotionally and associatively accessible to the audience of the target language (in our case the Greek language). On the other hand, don’t forget that it often describes another reality. It is a balancing act, sometimes a tightrope, but if the result gives an overall picture of the original work to a large extent, then the translation must be considered a success.

Sometimes the editor also plays a decisive role, at least in Greece: no matter how good and correct the translation of the translator is, sometimes the editor, who often does not know the author’s language, changes the author’s style radically, following Greek philological traditions based on atavisms: the Greek writer e.g. can swear all he wants, but a foreigner, especially a Northern European, is considered a being of a higher culture, so “go to bloody hell” becomes “please leave me alone” etc. (There are even worse examples). So we have to see here the role of the editor as well, perhaps even the role of the publisher also, but also of our philological traditions and atavistic instincts about how we are and how foreigners are and expected to be according to our views. I must say though that I have very good cooperation with far the most editors.

I do not agree that the translation is “unethical”. This is because, for me, literature and its value lays precisely in each people getting to know the culture and the mentality of other peoples, and there being an incentive for fruitful and constructive contacts between peoples and countries. In this way, wars, conflicts, the prejudices that create them, etc. are avoided. Otherwise, at least for me, foreign literature has no value in any country. Why should we read foreign authors if we don’t want to get to know their mentality, their culture and their country? Which, in the long run, leads to something even more ground-breaking: why should we read some authors in general, since we are not them? So why read at all if we don’t want to know a thinking different from our own? You understand that such opinions cannot stand, so, yes, both foreign and local authors should be read, in order to learn and enrich our thoughts and knowledge about the world. And if along the way some grammatical formulas are sacrificed, the gain is much, much greater. After all, there are wonderful translations of original works such as e.g. the Iliad in Danish, with hexameter and all the rules of technique, so here you can see the translator’s technique and intuition, how much of a “master” he or she is in the “marriage” of the two languages he or she deals with.

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

Here we do have a point: translators generally remain invisible in relation to authors. But steps can be taken, which must be initiated by the translators themselves: to demand their name to be mentioned, even with one word. This happens e.g. in Denmark, where every book review must mention the translator, even with one single comment, otherwise the medium in question (newspaper or anything else) is obliged to pay the translator a fine of 150 euros. But this was achieved by the Danish translators with much struggle, so it is high time people in other countries (like e.g. in Greece) did similar things. It has often happened to me to read book reviews, where the translator is not even mentioned in the formal details, where it is written about the book title, ISBN, etc. In general, we as translators ourselves must demand what we consider that improves our position, through our professional organizations and with joint action. Strength is always in union.

There should also probably be (just saying) translation awards such as e.g. Nobel Prize in translation, why not? If translation is taught, it is a science, so why shouldn’t it be treated like other sciences? Nobel Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, why not in Translation? At the same time, the money amounts of the translation awards, as well as other literary awards, should be increased. A prize in the Netherlands equivalent to the Greek State Translation Prize is 50.000 euros (fifty thousand Euros). In these ways translators can be seen more and enjoy the fruits of their labor.

Could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

I have answered this question indirectly above, but I am going to answer it now too: yes, of course, translation contributes enormously to the understanding of the culture, situation, living conditions of other peoples and nations. By reading foreign authors, we understand that other peoples are also humans, who have more or less the same concerns and searches as we have, and therefore we focus on what unites us and not on what divides us. It is no accident that, when there is a conflict, sooner or later the literary works of the countries, which one country is in conflict with, are banned or set aside: the purpose is that the people of the other country do not have human status in our eyes, and we can hate him more easily.

Translators are indeed cultural ambassadors between countries, peoples and societies. The reason that e.g. I became a translator, beyond language skills, is to contribute to the Greek public getting to know the Scandinavian reality and trying to transfer this reality – or some important elements of it, such as the welfare state – to Greece as well. I believe that my other colleagues from other countries have similar views: they all want to transfer a way of thinking and acting to another reality, so one nation can get to know another one. And so it should be. There are more things that unite us than those which divide us.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE