“For poetry there exist neither large countries nor small. Its domain is in the heart of all men”

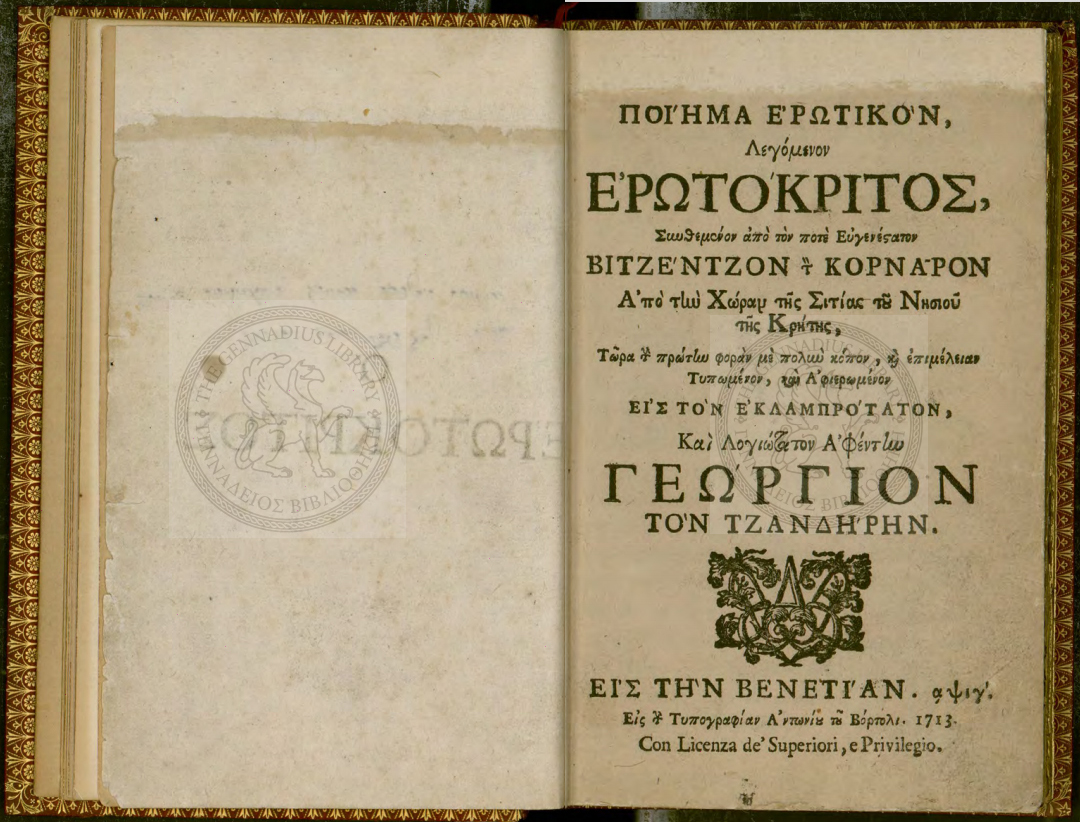

Giorgos Seferis

Throughout the centuries, the Greek language has been the quintessence of the Greek nation, the core of the Greek civilization and culture. It’s exactly this language, and more specifically the first literary text written in demotic Greek – that is the epic of Digenis Akritas (late 10th- early11th century)– that marks the first phase of modern Greek literature to last until the early 17th century when Vitsentzos Kornaros wrote his masterpiece Erotokritos. Indeed after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Greek literary activity continued almost exclusively in those areas of the Greek world under Venetian rule. It’s the Great Age of Cretan Literature (1570-1669), a golden period in the history of modern Greek literature, during which the Italian heritage was molded within the local fabric, elevating the Cretan dialect into an elegant literary language. Meanwhile, in the Ottoman-ruled areas, the folk song, which conveyed the aspirations of the Greek people of the time, became practically the sole form of literary expression.

Note: Erotokritos was first printed in 1713 in Venice. Three copies still exist from this first edition, one in the Gennadius Library in Athens, one in the Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana in Vicenza and one in the Public Central Library of Grevena.

It’s only towards the end of the 18th century that a number of intellectuals emerged who, under the influence of European ideas, set about raising the level of Greek education and culture, thus laying the foundations of an independence movement. The strong and recurrent moral support of the so-called ‘Fanariots’, namely the Greek minority living in Constantinople, invaluably helped materialize the cause, while it was the ‘Fanariotic literary school’ that introduced romanticism in prose and verses, epics and feuilleton story telling. The participants in this Greek Enlightenment also brought to the fore the language problem, each promoting a different form of the Greek language. Adamantios Korais is the leading Greek intellectual of the early 19th century, arguing for a form of Modern Greek ‘corrected’ according to the ancient rules, thus establishing “katharevousa” which was to become the official language of the newly born state.

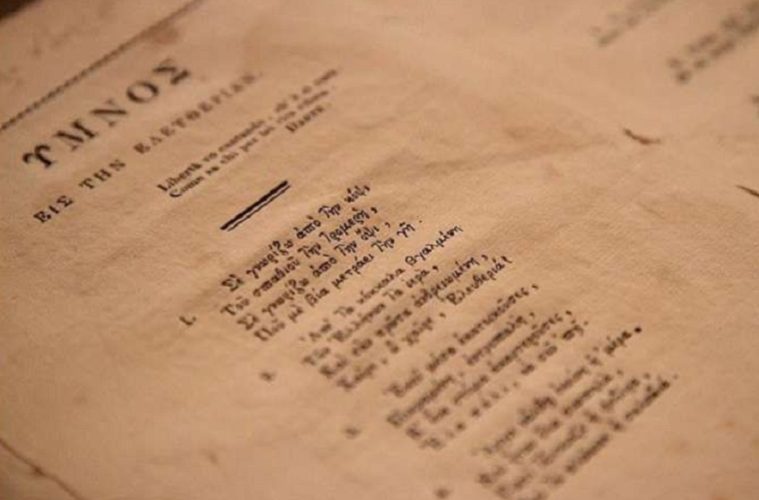

Meanwhile, interesting developments were taking place in the Ionian Islands where Romanticism acquired a broader signification, turning into a way of life as well as a school of aesthetics and social renewal. The leading figure of this romanticism are Andreas Kalvos and Dionysios Solomos, who gave birth to the Heptanesian School (1824-1910) and went on to become one of the greatest modern Greek poets. His Hymn to Liberty was widely acclaimed and gave extra strength to the philhellenic movement. Soon afterwards, Nicolaos Manzaros put the poem into music and the Greek national anthem was born.

Note: At 158 stanzas, Hymn to Liberty was written by Dionysios Solomos in 1823. Inspired by the Greek War of Independence, Solomos wrote the hymn to honor the struggle of Greeks for independence after centuries of Ottoman rule.

When Athens became the capital of Greece in 1834, it gathered together the literary voices of the periphery, thus turning into a hub of cultural activities. An “Athenian literary school” is formed promoting a late romanticism with strong French influences, while quarrelling about literary styles and more important about the language to be used in literature. During the same period (1830-1880) prose was dominated by two opposing trends: the historical novel, exceptionally represented by Emmanuel Roides and his masterpiece Pope Joan, and novels that are set in the present and tend to be satirical or picaresque in nature. Loukis Laras by Dimitris Vikelas is a case in point.

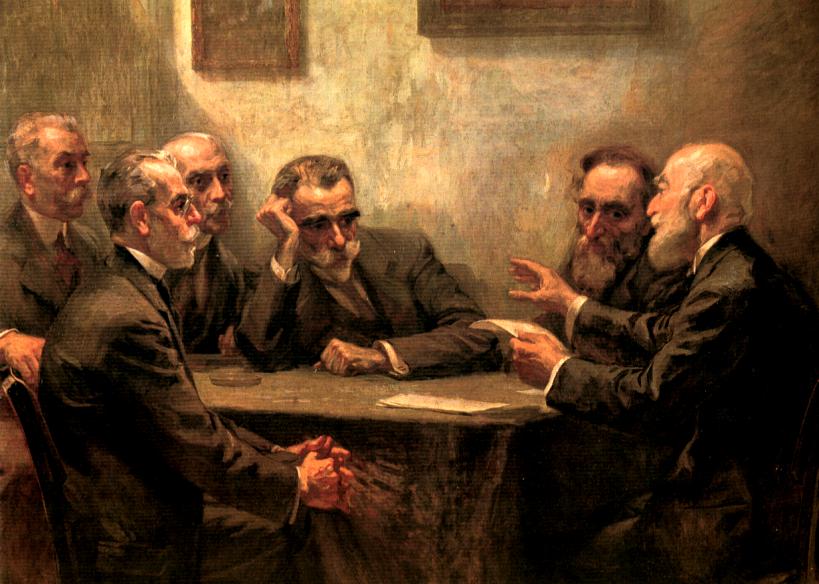

During the last two decades of the 19th century, Greek society began to set itself more realistic goals; a new bourgeoisie began to demand better state organization and to place faith in the parliamentarianism and in democratic principles. Within this framework, a “new” Athenian literary school will emerge. An outstanding member of this so-called generation of the 1880s is Kostis Palamas, who decisively contributed to the foundation of the new real literary environment, very close to the idea that the writer has a mission within society: to help it improve.

Note: “The poets” painted by G. Roilos depicts some of the most important representatives of the New Athenian school of poetry, also known as the Generation of 1880. In the middle, Palamas leaning on his hand. Depicted from left to right: Georgios Stratigis, Georgios Drosinis, Ioannis Polemis, Kostis Palamas, Georgios Souris and Aristomenis Provelengios reading a poem.

Poetry up to the first decades of the 20th century is represented by major Greek poets, such as Constantine Cavafy, whose one of a kind poetry exerted great influence on the generations to follow, Angelos Sikelianos, a visionary who attempted to revive the Delphic celebrations, Kostas Varnalis, greatly influenced by the Parnassians an Symbolists, Kostas Ouranis, who brought a cosmopolitan spirit into literature and of course Kostas Karyotakis, the link between the declining romanticism and the modernistic trends. Meanwhile, in prose, there appears the short story genre, which focuses on the depiction of traditional rural life, sometimes idealized and sometimes viewed critically by the authors. Georgios Vizyinos is considered the pioneer of the Greek short story, while Alexandros Papadiamantis is among the most prolific short story writers, whose work is considered a true literary gem.

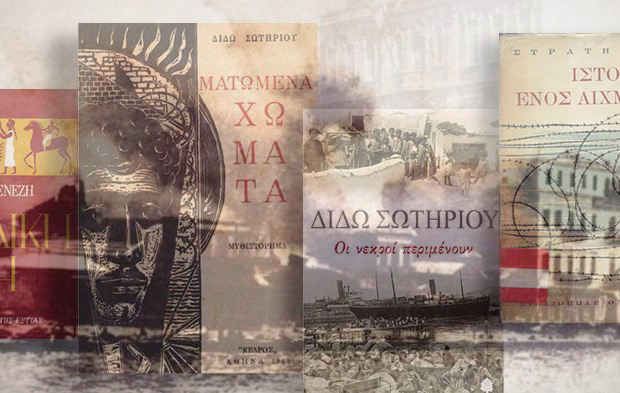

One of the milestones of 20th century Greek national narrative is the Asia Minor Catastrophe, i.e. the defeat of the Greek Army in the Greek-Turkish war (1919-1922) and the resulting wave of refugees of Greeks from Asia Minor to the Greek state. Literary representations of life in Asia Minor and of the refugee experience played a crucial role in that. Indeed, a significant number of widely-read and influential novels and short stories concerned with this experience have appeared since 1922. Some of these texts are central to the canon of modern Greek literature, namely Land of Aeolia, Number 31328 and Serenity by Ilias Venezis, Farewell Anatolia by Dido Sotiriou, A Prisoner of War’s Story by Stratis Doukas, At Hadzifrangou by Kosmas Politis etc.

Greek literature will enter modernism with the so-called “generation of the 1930s”, a group of writers who sought to combine European influences with the best of what was Greek, opening new horizons in literature. Giorgos Seferis, awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1963, is the leading figure of this generation, adapting and incorporating new literary trends in his poetry. Odysseas Elytis, the second Nobel laureate 1979, celebrates the Aegean scenery as an ideal world of sensual enjoyment and moral purity, while Andreas Embirikos stands as the emblematic figure of surrealism in Greece. And, of course, Yiannis Ritsos, one of the most prolific poets of modern Greek literature, deserving for himself the role of the bard, fighting for the dignity of the individual. The most famous novelist of the period is beyond doubt Nikos Kazantzakis, a prolific and versatile writer, traveler and poet.

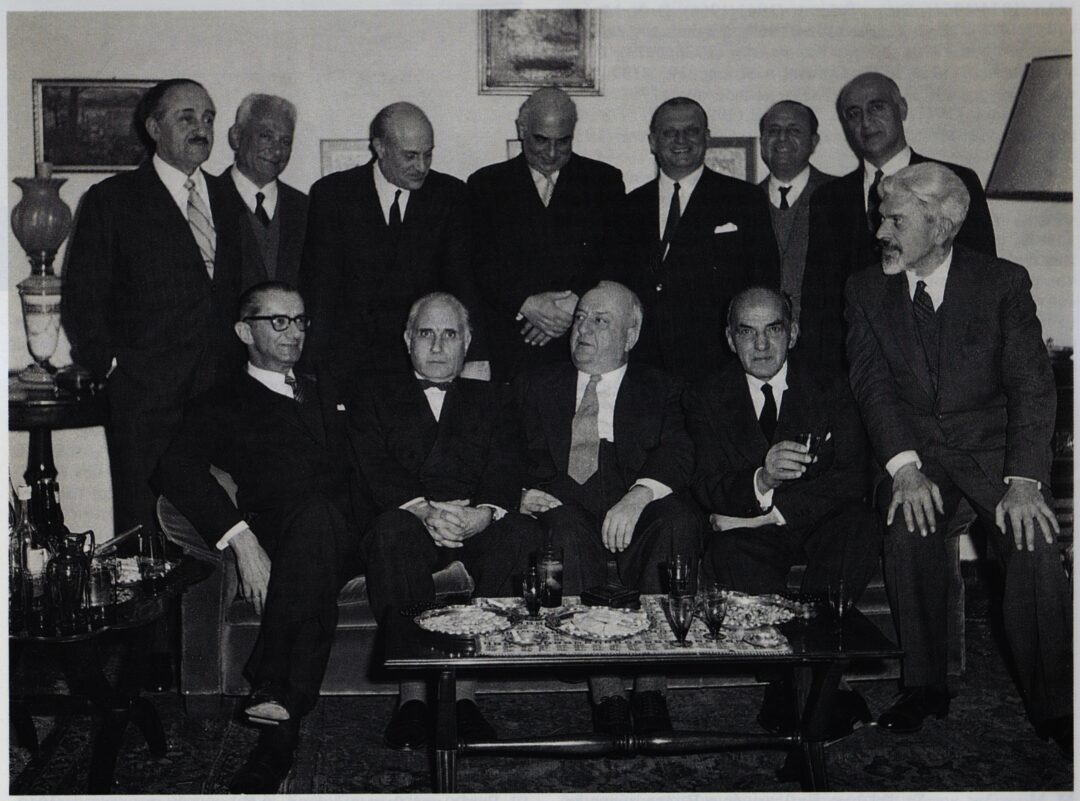

From left to right/ (Standing) Τhanassis Petsalis, Ilias Venezis, Odysseas Elytis, Giorgos Seferis, Andreas Karantonis, Stelios Xefloudas, Giorgos Theotokas. (Sitting) Angelos Terzakis, Konstantinos Dimaras, Giorgos Katsimbalis, Kosmas Politis, Andreas Empeirikos.

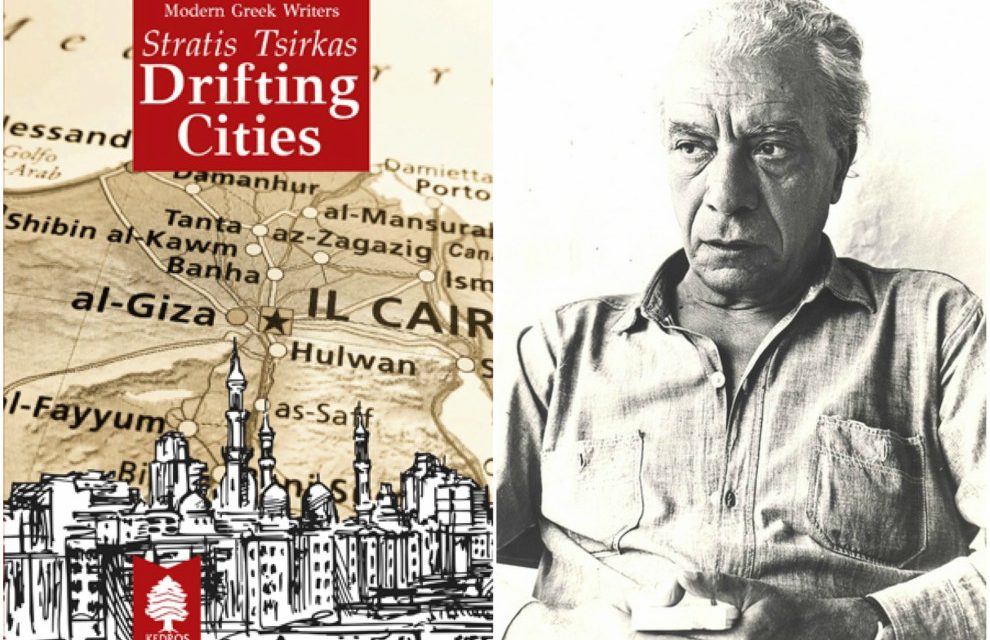

The second half of the 20th century is marked by a series of events that left deep wounds in the social fabric. The Second World War, the German Occupation, the Civil War that came immediately after, the dictatorship of the colonels in 1967 are the main historical events that poisoned public life. Within this framework, during the 1960s writers attempted to explore the historical factors underlying the contemporary social and political situation. Dimitris Chatzis, Kostas Tachtis, Yorgos Ioannou and of course Stratis Tsirkas with his masterpiece Drifting Cities are among the most prominent representatives of the period. As for poetry, although no individual poets of the postwar generations tower above the rest, Manolis Anagnostakis, Miltos Sachtouris and Takis Sinopoulos are among those with the greatest reputations.

Note: Drifting Cities, the emblematic trilogy of Stratis Tsirkas, is considered one of the most popular and widely read works of literature in Greece. The trilogy (The Club, Ariagni, The Bat) is a saga of three cities: Jerusalem, Cairo and Alexandria, drifting toward chaos in a war-torn Middle East.

Yet, those who began writing immediately after 1974 hastened to disengage their work from the drama of politics and history and clearly differentiated themselves from the attitudes and choices of their predecessors when literature was translated into a political act. During the 1980s, the novel will take over from poetry as the most prestigious genre in Greek literature. Indeed, while the generations of the 1970s and 1980s produced a handful of exceptional poets, poetry underwent a fundamental crisis of public meaning, overshadowed by the Greek postmodern novel, exceptionally represented by Aris Alexandrou, Thanassis Valtinos and Maro Douka just to name a few prose writers, which earned critical and popular recognition.

On the threshold of the 21st century, a new kind of literature is flourishing, attempting to change the arts landscape in Greece. Well educated and with a strong civic presence, global and with an artistic fervor, these young poets and prose writers dominate the public sphere, with their work popping up not just on magazines, small presses and websites, but on graffiti walls, in music, film and art. Narrating their hopes and fears, unfolding their dreams and expectations about the future, they certainly manage to debunk stereotypes and help form a new Greek identity. Supposing it marks the coming of a new area, one has to be confident, as Andreas Embirikos said, “we are all within our future”.

A.R.

Read also: ‘Hymn to Liberty’ by Dionysios Solomos; “The Free Besieged” by Dionysios Solomos; The Olympic Hymn by Kostis Palamas; ‘Ballad for the Unsung Poets of the Ages’ by Kostas Karyotakis; “Christmas Short Stories” by Alexandros Papadiamantis; A look back at Greek writers nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature; A Tribute to Odysseus Elytis and his Chef d’ Oeuvre ‘The Axion Esti’; ‘Body of Summer’ By Odysseus Elytis; ‘Summer Solstice’ by Giorgos Seferis; A Tribute to C.P. Cavafy; ‘Moonlight Sonata’ by Yiannis Ritsos; “The Body and the Blood” by Yannis Ritsos;The Asia Minor Catastrophe in Modern Greek Literature; “Farewell Anatolia” by Dido Sotiriou; A Prisoner of War’s Story by Stratis Doukas; Drifting Cities by Stratis Tsirkas; Land of Aeolia” by Ilias Venezis;Manolis Anagnostakis: A poet of defeat and infinite hope; ‘Winter 1942’ by Manolis Anagnostakis; “The Carnival” By Miltos Sachtouris; ‘Mission Box’ by Aris Alexandrou;‘Data from the Decade of the Sixties’ by Thanassis Valtinos; Maro Douka on the Conversation between Literature and History and the Decisive Role of Language

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE