Eveline Mineur (1997) is a translator of modern and contemporary Greek literature and an independent editor for various cultural institutions. She studied Literary and Cultural Analysis and Modern Greek Studies under the supervision of Prof. Maria Boletsi, who holds the Marilena Laskaridis Chair of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Amsterdam. Early 2022, she was selected by the Dutch Expertise Centre for Literary Translation for its development programme for promising novice translators. Since then, her translations have been published in leading literary magazines in the Netherlands and Belgium, such as Poëziekrant, tijdschrift Terras, Kluger Hans, Revisor and Awater.

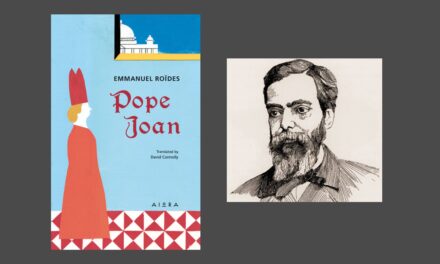

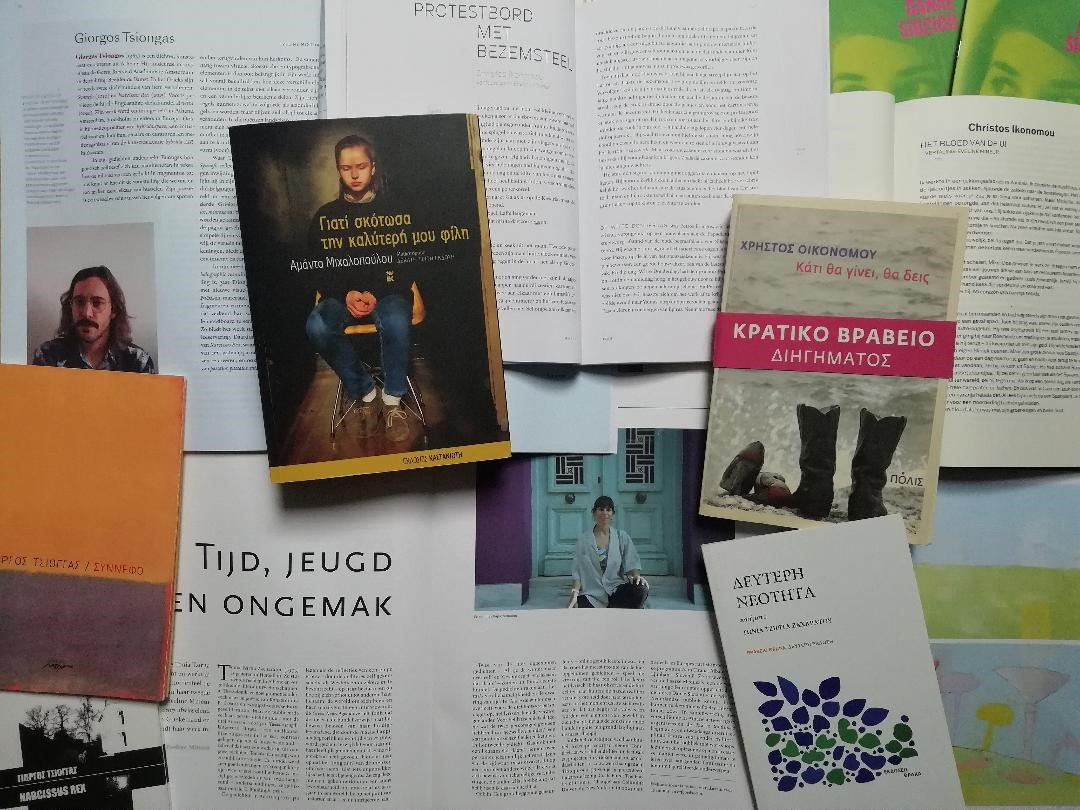

In 2023, she was approached by Poetry International, an international poetry festival that takes place annually in Rotterdam, to translate the poems of Danae Sioziou, the first Greek poet programmed at the festival since 2003. That same year she translated an adaptation by Konstantinos Vasilakopoulos of Yannis Mavritsakis’ play Fucking job, which received an excellent review in the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant. In 2024, Eveline received a grant from the Dutch Foundation for Literature to produce a translation sample of Christos Chrissopoulos’ novel The Parthenon Bomber. She is currently working on her translation of Amanda Michalopoulou’s novel Why I Killed My Best Friend (Kastaniotis Editions, 2003), which is scheduled to be published by Uitgeverij HetMoet in May 2026.

How did your involvement with Greek language and culture begin? What about your interest in Greek literature, both prose and poetry?

I have relatives in Greece and during my childhood we used to visit them every summer. Before starting my studies in Amsterdam I spent a couple of months on Rhodes and started to learn the language. Every Friday the whole family would gather at my cousins’ grandparents and we would eat together. My desire to follow their conversation and properly thank them for their hospitality led me to take Greek lessons and my love for and interest in languages did the rest. As a visitor, I also considered it a sign of respect to approach my then neighbours, local shopkeepers etc. in their own tongue. I enjoyed how people’s attitude changed when I approached them in Greek. This very quickly gave me a feeling of belonging. I was also lucky enough to be taken up in a group of friends who had – and still have – the patience to explain Greek phrases to me and teach me new words. This was the beginning.

Once I had returned to the Netherlands to study comparative literature, a friend gifted me two volumes of Cavafy’s poetry. I started translating some of the poems in order to read them. You could actually see the influence of Cavafy’s writing on my early Greek: I once texted a friend επεράσαμε ωραία. Perhaps little surprisingly, I missed the life I had left behind on Rhodes, and learning Greek became a way of staying connected and curing homesickness. During my studies I stumbled upon a minor in Greek studies, which allowed me to practice the language on a daily basis. Eventually I did the whole bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in translation studies. Thanks to the efforts of Tatiana Markaki, the University of Amsterdam still has a department of modern Greek studies, despite severe budget cuts. I have had excellent teachers there, who have further inspired my interest in Greek prose and poetry and always encouraged me, such as Maria Boletsi, aforementioned Tatiana Markaki, Despina Moysiadou and Arthur Bot.

Translations and Publications

Which have been the major challenges you have faced so far while translating Greek literature into Dutch?

After being selected for a development programme for promising early-career translators, I got off to a flying start. With the help of experienced translators Katelijne de Vuyst and Hero Hokwerda my translations quickly appeared in a number of literary magazines in the Netherlands and Belgium. Contemporary Greek literature is very niche here and people seemed eager for new stories. The next step, finding a publisher who would let me translate a Greek novel, proved more challenging. It took a lot of perseverance to find a publisher who was willing to take the financial risk of publishing a contemporary Greek author as of yet unknown in the Netherlands.

Alarmingly, translated fiction has been under pressure in the Netherlands for at least a decade. Whereas a decade ago more than 10 of the 100 best-selling books here were literary translations, in recent years this number has dropped to only 2. When it comes to the selection of foreign titles in such a climate, publishing houses tend to avoid (financial) risks, which results in a lack of diversity in translated fiction and an absence of new voices. The past couple of years, the only translations of Greek books that have been published by traditional publishers were either non-fiction bestsellers, such as Stefanos Xenakis’ The simplest gift and Ted Papakostas’ How to Fit All of Ancient Greece in an Elevator, rediscovered modern Greek classics like Margarita Liberaki’s Three Summers or books that have won an international literary award, such as Christos Chomenidis’ Niki.

Fortunately, both the Dutch and Greek Ministries of Culture offer grants that encourage the publication of literary translations. I could not stress enough how important this type of financial support is. Thanks to these grants, a number of smaller, independent publishing houses in the Netherlands is able to invest in translations of unknown foreign talent, resulting in a more diverse Dutch literary landscape. I am confident that when Dutch readers will discover what contemporary Greek literature has to offer, the demand for translated fiction from Greece will grow. More visibility quite simply creates more demand. An example would be the poems of Danae Sioziou that I translated for the Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam last year. They made such an impression on Dutch poet Ingmar Heytze that he read some out loud on a national radio show. Soon after I was approached by poetry magazine Awater, who asked me if I knew any contemporary Greek poetry similar to that of Danae. I took the opportunity to introduce them to Tonia Tzirita Zacharatou. In this way, one translation at a time, I hope to give Dutch readers an impression of contemporary Greek literature.

Danae Sioziou and Eveline Mineur at Poetry International

Does Greek literature have the potential to move beyond national borders and attract Dutch readers? Which are the main difficulties in this process?

Absolutely! Εvery country has books that transcend the cultural specificity of the society in which they were created. The short story collections Something Will Happen, You’ll See and Good Will Come From the Sea by Christos Ikonomou come to mind. Even though the topics tackled in these stories are framed by Greek circumstances, they are also universal: financial struggles and unemployment, the search for meaning in life, the experience of loneliness and hope for a better future against all odds. Such topics are recognisable to readers all over the world, including a Dutch readership.

I don’t think that there is some aspect particular to literature produced in Greece that prevents it from moving beyond national borders. What might slow down the dispersion of Greek literature in the Netherlands, though, is the current lack of connections between the Dutch and Greek literary fields. In my experience, language and cultural differences can still be a barrier for Dutch publishers when approaching Greek literary institutes. For instance, if a Dutch publisher is interested in purchasing a Greek title, they would probably reach out by e-mail rather than picking up the phone. If that e-mail is never replied to, for whatever reason, the lack of response would likely be taken as a sign that the people on the other end are either not interested or difficult to reach. Personally, I often assist Dutch publishers in establishing relations with Greek publishers or authors by picking up the phone or even going to Greece to meet people in person. Of course this is not a reply to what the main difficulties are in Greek literature attracting Dutch readers, but what stops it form reaching them in the first place.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

It is commonly agreed that the translator has a responsibility to stay true to the ‘essence’ of a text and to respect and reproduce the style or ‘voice’ of the author. I like to think of it as an unwritten contract between the translator and the reader: when a reader picks up a translation, they should be able to trust that the text in front of them is to a certain extent interchangeable with the source text, because intuitively they will treat it that way. People will form an opinion of the author and their work, based on the translation they read. Willfully changing elements in the text that will impact the overall style or content of a work could in that sense be seen as unethical.

Since literary translation is a form of artistic writing it is not always easy to tell at which point the interventions of a translator – or of any of the other actors involved in the process of production of a translation, such as authors, rights holders, agents, editors and publishers – become unethical. I recently read about the reception of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin in Greece: apparently the Greek translation downplayed or left out fragments that shone a bad light on the Greek communist movement during the occupation by the Axis powers. Without knowing the details of this specific case, I would call downplaying or outright censoring certain style or factual elements an example of unethical translation. After all, if the author took a certain political position that is seen as unfavourable in the target culture, the reader still has the right to know.

Detail of Christos Ikonomou in literary magazine Kluger Hans

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

Embedded in this question lies another, perhaps even more pressing, question: why is visibility so important? Raising awareness of the role of the translator, both with publishers and the general public, will lead to the recognition that translators deserve as co-author of the translated work. Consequently, it will help translators to improve their financial situation, for literary translators are still direly underpaid. Increasing the translator’s visibility will give them a more powerful position when negotiating pay, royalties, deadlines etc. Besides visibility, the issue of fair pay calls for solidarity: colleagues who are not solely dependent on the income of their translation work, should not accept low rates. Of course, publishing houses are not our enemies here: translators should educate themselves well and inform their publishers of funding possibilities. Fair pay is an important aspect of the professionalization of literary translation and increased visibility can help us achieve this.

I do believe that, thanks to the efforts of a number of activists and unions, translators in the Netherlands are slowly gaining visibility. Unlike before, mainstream news outlets now publish articles about translators and translation. More literary translators have started to engage in public discourse and some translators have found ways to increase their visibility through social media. Recently, a talented young translator here in the Netherlands has even hired a manager to see to his affairs, just like a successful author, musician or actor might do. These are all steps in the right direction.

In the Netherlands we see many good examples of bringing translators to the forefront: they are invited as speakers at literary events and festivals and a growing number of publishers include their name on the book cover. At times you will even find the translator’s biography beneath that of the author. It is a good development that more and more publishing houses and book sellers start to realize that translators can be valuable partners, acting as ambassadors of the books that they translate, who can help to promote their books and bring them under the attention of a wider audience.

Could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

Certainly. You asked me earlier if Greek literature has the potential to move beyond national borders and I replied that certain stories are not confined to a particular culture, because they address topics that speak to readers all over the world. At the same time, precisely those elements that set contemporary Greek stories apart from the stories a Dutch audience might be familiar with is what makes them such valuable additions to the Dutch literary landscape.

One of the things that drives me as a translator is exposing Dutch readers to a different mentality and to the different approaches to life, family, work and the state that the works I translate might offer. After all, literature has the potential to inform people of views different from their own and make them reconsider pre-existing beliefs. Reading (translated) fiction is a way to train your empathy, it inspires a sense of cultural curiosity and humility – as opposed to dangerous ideas of cultural superiority or indifference. Ultimately, I believe that reading translated literature makes us better people, in the sense that it cultivates empathy and fosters cultural open-mindedness. And this is exactly what we need in times of growing polarization.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE