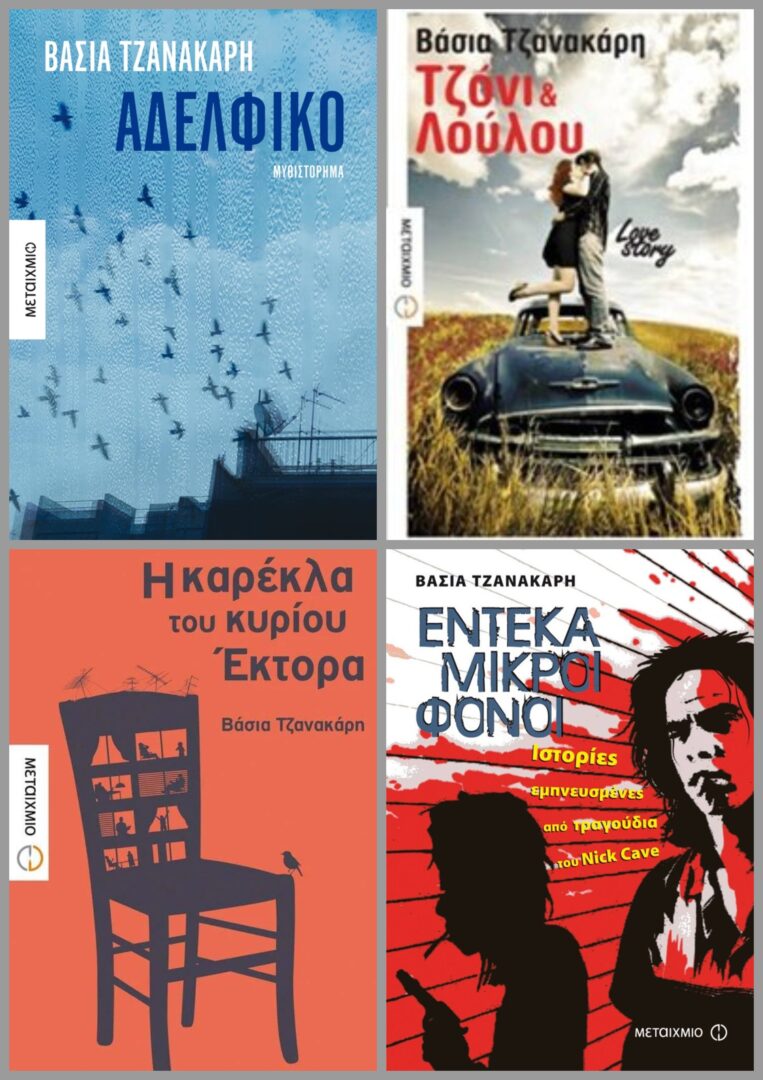

Vasia Tzanakari was born in Serres, Greece. She studied English Literature in Thessaloniki and continued with postgraduate studies in Translation-Translation Studies in Athens. She published her first book, Έντεκα μικροί φόνοι: ιστορίες εμπνευσμένες από τραγούδια του Nick Cave [Eleven Little Murders: stories inspired by Nick Cave songs], in 2008. She went on to write another short story collection, two novels and a children’s book. Her latest book is a short text narrative, called Γεννιέται ο κόσμος [The world is born]. She has been nominated for various literary awards, including Best new author by Diavazo Magazine for her first book, as well as for her 2020 novel, Αδελφικό [Adelfiko], nominated for Best Novel award by O Anagnostis magazine, the Athens Prize of Literature for Best Novel, and Best Novel by Klepsydra magazine.

As of 2010 she works as a translator, having translated works by Virginia Woolf, Margaret Atwood, Ian Rankin etc. She has received awards for the translation of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own by the Association of Greek Translators of Literature, Ian Rankin’s Saints of the Shadow Bible by Public Book Awards and Kimberly Brubaker Bradley’s Fighting Words by the Greek Ibby-The Circle of the Greek children’s books. She lives in Athens.

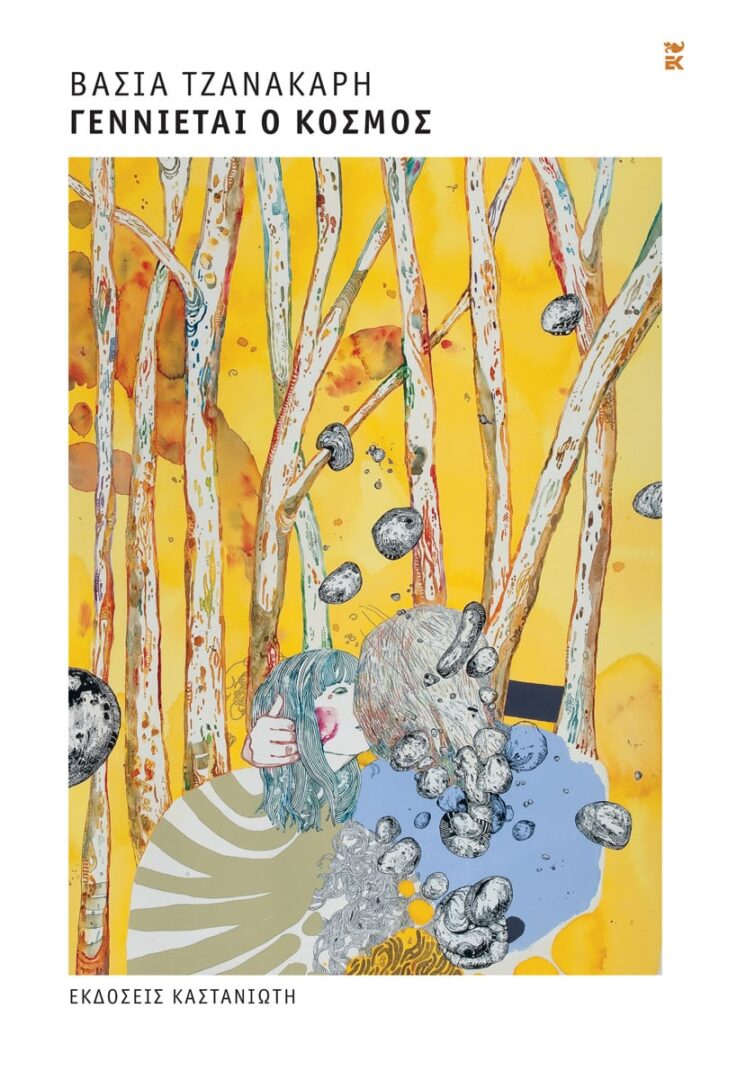

Your latest writing venture Γεννιέται ο κόσμος [The world is born] has just been published by Kastaniotis. Tell us a few things about the book.

My new book is the story of a budding love narrated in fragments. It is basically about how love changes the way we perceive the world, how a universe of two is born when two people meet. This is a really exciting notion for me. So, a man and a woman in their forties meet and unexpectedly fall in love. The narrator of the story is the woman, and what she does is that she practically expresses her love for the new man in her life through short texts, ending up describing their first year together. She has all these thoughts and feelings she hesitates to share with him so it’s like love letters meant to be read by him, but somehow they end up in the readers’ hands. The title comes from a lyric by Octavio Paz, made into a song by Thanasis Papakanostantinou. The book is divided into four parts, four seasons or the four sides of a double LP. The world is born is quite different from anything I’ve previously done, short form, more poetic style. The cover is a 2015 work by renowned artists Stefanos Rokos — I could not think of a more suitable cover, capturing the essence of the book.

Which are the main themes your writings touch upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

Love in all its forms, I guess, human relationships, the internal journey to the realisation of the self, the battle between light and darkness, hopefulness and despair, optimism and pessimism. I’m also interested in the idea of place, whether writing about a magical village in my hometown, Serres, in the case of Adelfiko or about Athens and its myriad intricacies. I love my neighbourhood, Kypseli, it plays a vital role in The world is born. I think that I’m forever writing about feelings, probably because it’s one of the hardest things to figure out and express, so it’s like an exploration for me.

Death is also a recurrent theme in my books, I find it to be so overwhelming, I touch upon it in my writings because it terrifies me. I’m thinking that maybe that’s the reason I was so into gothic music and Nick Cave-ish stuff, love and death, the two main poles of life. Speaking of music, that’s another theme in my books. Music is my favourite form of art and it keeps finding its way into my books. Sometimes it’s the main inspiration (my first book is inspired by the works of Nick Cave) others the heroes voice their musical tastes and listen to music. In The world is born, apart from the title, there are also some hidden references to Lena Platonos and Pavlos Pavlidis, but I also think the texts themselves have a melodic quality.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is equally important as the story I want to narrate. I always try to work on it as much as I can. I think I finally found my style in Adelfiko and my new book is a more refined version of that language. The texts are short, some of them two or three lines, and the rhythm, the melody, the sound of the words are very important for the vibe, the feeling of the book and my personal aesthetics. I read quite a lot of poetry, I think it shows, but I am not interested in writing poetry. Somebody told me once that fiction writers should read poetry and vice versa. I don’t remember who said that to me but they were right! There are some poets referenced in the book, particularly Ritsos, Cavafy, Kavvadias.

Where does the writer meet the translator in your work?

It’s quite common in Greece for writers to work as translators because you can’t possibly make ends meet through writing. It’s quite a challenging combination. On the one hand it’s a constant exercise in language and ideas, so that’s a good thing. On the other hand, you kind of lose your own voice in the process, especially when writing a novel, you have to leave one world, so to speak, and enter another.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

That is quite the case. When translating, quite a lot of things are inevitably lost. I think Frost’s famous quote about poetry getting lost in translation describes pretty accurately the challenging nature of translation. Poetry is a literary genre so language-oriented that it constitutes a perfect example for the difficulties encountered when trying to transfer a text into another language. Translating a novel, a poem or a short story means creating a new text in another language, that will be added to the literary canon of the translated literature of the target language. However, it is forever intrinsically tied to the original.

Therefore, it is a translator’s ethical obligation towards the text and the writer to try and maintain the rhythm, the melody, the puns, the tone, the style, the form, the meaning. To do so, translators have to be up-to-date with the source language and its changes (English for example changes rapidly), the surrounding culture and the writer’s works, as well as with the changes in the target language.

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

The translator’s transparency has been a controversial issue in translation studies, based on Venuti’s theory. Venuti holds that it’s quite problematic to focus on the ‘fluency’ of a translation in the sense that in order to achieve this fluency, certain aspects of the source language are disregarded, leading to the illusion that the translation is not a translation, rendering the translator invisible. This idea has been the subject of a lot of debate. All theory aside, I think there has been some change, readers are becoming more interested in translators and publishers actually put their names on the covers more often than not. However, what is not understood is that it is a very demanding job and a great responsibility, and for this it should be also a better paid job. As translators we must come together and fight for our rights. It is a solitary job but we’ re in it together.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE