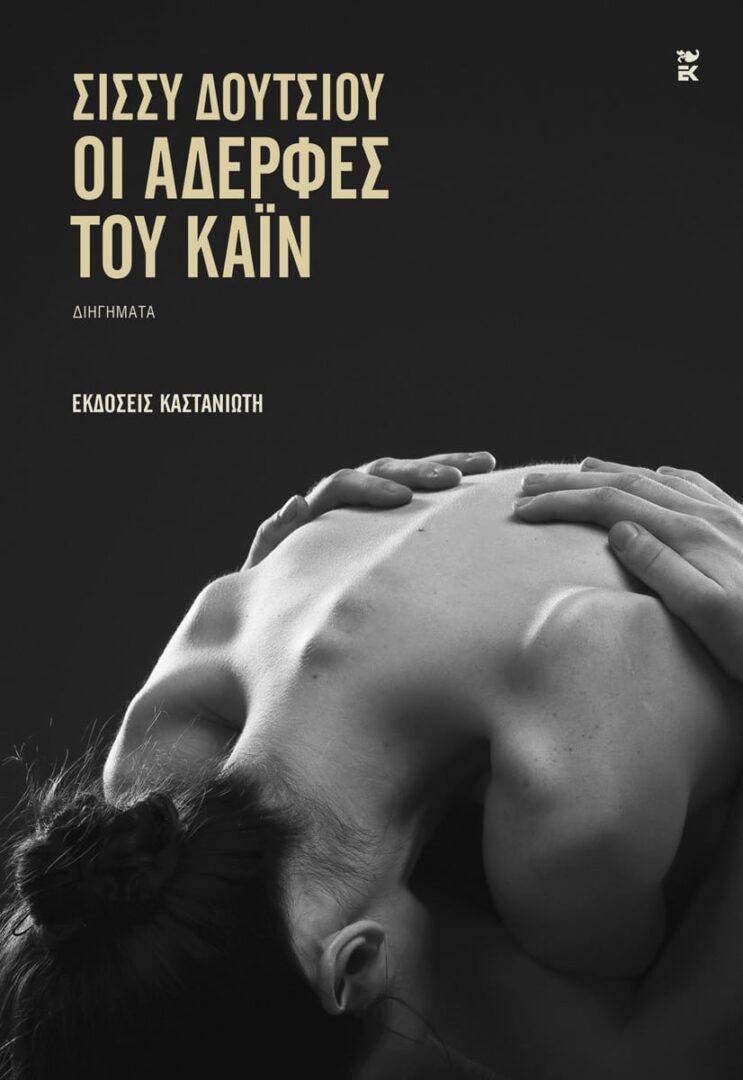

Sissy Doutsiou is an actor, a founding member of the Institute for Experimental Arts and curatior of the annual International Video Poetry Festival in Athens. A spoken word pioneer in Greece. She toured with plays, poetry readings, performances and lectures in Europe, US and Asia. Her latest book The Sisters of Cain was published by Kastaniotis.

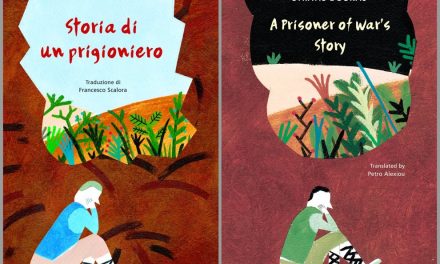

Your latest writing venture Οι αδερφές του Καϊν [The Sisters of Cain] (Κastaniotis, 2023) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The Sisters of Cain consists of four stories written during my travels to far away lands, requiring focused discipline in their creation. By observing romantic dispositions, dark moments in long-term relationships, emotional bonds among my friends, violence against trans individuals, the tedium in heterosexual relationships, the daily life of lower social classes, exploitation, and gender inequality, I wrote “Women in Tucson, Arizona,” “Black Sea Urchin,” “The Ghost in the Foreground,” and “Lady Boy.”

The Sisters of Cain are four tragedies, more than just fascinating portraits of phantasmagorical women. They are revealing stories of liberation from deep trauma that has caused considerable pain. The Sisters of Cain are women who have decided to strip anyone of the power to humiliate them. There is no forgiveness in this book, no mercy, no courage to change life but rather to destroy it. There is jealousy and anger and rage and hatred and the first murder. The Sisters of Cain deliver the heaviest punishment – death, to find rest, to find catharsis. They feel wronged, that their only solution is to devise a plan, a secret of their own, six murders. They choose violence to accelerate justice.

The book reveals moral dilemmas that define our era when we face ruthless injustice and the cruelty of a social system that causes us mental illness, conditions of loneliness, sadness, and disappointment. My writing consistently explores themes of patriarchal oppression, gender violence, the exploitation of vulnerable individuals, class struggles, and the search for liberation through radical means. The stories reveal how everyday life intersects with deeper systemic issues of power, control, and resistance.

These themes are woven through my work whether I’m writing about homeless actors, young servants in South Africa, women in Arizona, or sex workers in Bangkok. Each story examines how individuals navigate and ultimately rebel against systems of oppression.

My involvement with Void Network and the poetry community of Voidness Publications greatly contributed to this journey. My four poetry collections and my first anthology of short stories, our discussions, spoken word events, and poetry festivals provided me with the emotional strength and experience that led to The Sisters of Cain.

Which are the main themes your writings delve into? Are there recurrent points of reference in your work?

My work explores the fundamental themes of eros and critical consciousness, examining how people create lives of meaning beyond prescribed social roles. Like Emma Goldman, I’m fascinated by how passion and desire can break the chains of conventional existence. Anaïs Nin’s profound explorations of feminine sexuality and consciousness have deeply influenced my writing – particularly her courage in depicting women who dare to live by their own rules, outside society’s expectations.

I draw inspiration from revolutionary thinkers like Lucy Parsons, who envisioned and lived a life dedicated to human liberation, showing how personal and societal transformation are deeply connected. Voltairine de Cleyre’s powerful poetry and essays on feminism and free thought illuminate the possibility of creating autonomous spaces where people can fully express their humanity, rather than being reduced to mere productive units in an economic machine.

The raw emotional honesty of Anne Sexton and Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry shapes how I approach writing about personal liberation. Their fearless examination of inner life and desire reflects my own interest in how people break free from social conditioning to discover authentic ways of being. Like Nin, I explore the hidden realms of consciousness, revealing how intimate experiences can spark broader awakening.

Throughout my work, there’s a vital connection between erotic power and critical thinking. I examine how people resist the systems that try to standardize their lives, finding ways to live according to their own rhythms and desires. My writing celebrates those who choose to craft their own destinies, refusing to submit to the dulling routines of conventional existence.

How does literature converse with its surrounding reality? Does it constitute a way to talk about the past and at the same time envision a radically different future?

Literature can increase our capacity for empathy and social understanding. Writers expose us to fictional situations while revealing the secret thoughts of characters. Fiction can help us gain important life experiences without having to endure pain or ecstatic joy ourselves. They offer us simulations of the social world. Literature acts as a bridge between inner truth and outer reality, creating spaces where personal experiences collide with and transform our collective imagination. When we write about desire, freedom, and the yearning for different ways of living, we’re not just documenting the present – we’re actively participating in creating new possibilities.

The act of writing itself becomes a form of resistance when it dares to express what lies beyond conventional thought. By exploring the territories of desire and consciousness that society often tries to suppress, literature creates sanctuaries where forbidden dreams can take root and grow. These dreams, once expressed, begin to reshape our sense of what’s possible.

When we write about the past, we’re not simply recording history – we’re engaging in dialogue with those who dared to imagine and live differently before us. Their courage in breaking from prescribed paths becomes part of our present conversation about freedom and possibility. Through literature, their radical visions continue to breathe and evolve in our contemporary moment.

The future emerges in literature not as mere fantasy, but as a tangible possibility born from our current struggles and desires. By giving voice to what’s silenced or dismissed in mainstream discourse – be it erotic power, radical thought, or alternative ways of living – literature helps us imagine and therefore begin to create new realities. It shows us how personal liberation and social transformation are intimately connected.

In this way, literature becomes both witness and midwife to change, helping birth new ways of thinking, feeling, and being in the world. It reminds us that the future is not a fixed destination but something we actively create through our ability to imagine and articulate different possibilities.

What about the political aspects of gender and their revolutionary potential in literature?

In a cultural environment where hyper-individuality and self-sufficiency are highly valued, we fear the empathy that love requires. Mutual love is difficult in a society obsessed with consumerism, individualism, and self-improvement. Our relationship with ourselves has become our most important project. We’ve long been socialized to consume – we consume material goods, experiences, even people. Sex has been a commodity for centuries, millennia. Romance can be sold – as Valentine’s Day chocolate hearts. Only love is difficult to package: how do you profit from something freely given and, at its best, unconditional?

In a capitalist society, love becomes not only outdated but problematic. Capitalism redefines “love,” distorts its meaning and replaces it with “partnership” or “sex.” These ideas are much easier to sell. Every point of human meeting or connection has been transformed into a battlefield of social war, exploitation, and imposed inequality. Love in modern metropolises has vanished; we see each other as products in a shop window.

The political aspects of gender in literature become a powerful tool for exposing these systemic inequalities. In The Sisters of Cain, the female characters refuse to submit to patriarchal power structures, choosing instead to confront the violence inherent in these systems. They reveal how gender oppression intersects with economic exploitation, showing that the struggle against patriarchy cannot be separated from the fight against capitalism. My writing aims to expose how gender-based violence and inequality are not isolated incidents but systematic manifestations of power.

Literature has the revolutionary potential to imagine different ways of being, loving, and relating to each other beyond the constraints of patriarchal capitalism. Through my characters – whether they’re the women in Tucson, the homeless actress, or the trans individual in Bangkok – I explore how resistance to gender oppression can take radical forms. These stories aren’t just about individual liberation; they’re about collective rebellion against a system that commodifies our bodies, our desires, and our capacity to love. The revolutionary potential lies in exposing these mechanisms of control and imagining ways to dismantle them.

CP Cavafy Professor Emeritus of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature Vassilis Lambropoulos has argued that “the bankruptcy of the revolution, along with the exhaustion of post-colonial emancipation, have inspired in Greek poets a combination of resignation and resilience which I have been calling “left melancholy.” How is this left melancholic feeling imprinted in the work of contemporary Greek poets both in terms of class and gender?

“Left melancholy,” as defined by Lambropoulos, requires a radical re-examination through the prism of underground and radical poetic voices. As Benjamin notes in his theorization of “left-wing melancholia” – a condition where revolutionary defeat transforms into a form of attachment to loss itself – it takes on special significance in the contemporary Greek context.

“Left melancholy” in contemporary Greek poetry intersects with a deeper existential dimension of loss. The slogan ‘No Hope’ left by Void Network on the walls of Athens encapsulates this dialectical relationship between tearful pain and incisive rage, which generates an urgent need for mutual understanding and transcendence of the self’s limitations. Poetic writing articulates a critique that surpasses traditional leftist analysis, recognizing that the state and money are not merely structures of power but weights that crush the very possibility of collective care and freedom. The left, which once promised emancipation, ultimately contributed to the dissolution of the vision – leaving behind a generation seeking not a new ideology, but a way to understand and overcome deep frustration.

In terms of gender, contemporary Greek poetry of the 21st century forms a complex dialogue with dominant power structures. “Left melancholy” emerges as an analytical tool through which patriarchal mechanisms, heteronormativity, and power relations of the post-transitional era are examined. The poetic writing of this period is characterized by an incisive deconstruction of the ways in which collective struggles and political loss are experienced and articulated through the prism of gender identities and sexuality. This process is transformed into a complex field of queer and feminist critique that runs through the entire social sphere, bringing to the forefront the contradictions of gender hierarchies at every level of collective experience.

At the class level, this poetry captures the deep existential trauma of a generation that saw its dreams crushed under the steamroller of crisis. The fear of the suspended, the sense of perpetual anticipation of a catastrophe that has already occurred, penetrates the verses as a dark prophecy that has been verified. However, melancholy here is not just the recording of loss. It becomes a stubborn refusal of resignation, where disappointment becomes raw material for a new poetic language seeking ways to salvage the revolutionary promise.

The intersectionality of gender and class is inscribed in the body of poetry as a multilayered mapping of the contemporary condition. The verses capture the interconnection of oppressions, where labor precarity meets both the violence of normative standards and the possibility of choosing how we want to exist in a world full of stylized bodies and gender identities. Poetic language, measuring itself against the limits of representation, attempts to capture this multiplicity of experience. This search for new ways of expressing collective experience transforms into a deeply political process where individual consciousness meets the collective dynamics of resistance.

The “resignation and resilience” that Lambropoulos identifies thus becomes a continuous negotiation with loss, a refusal to accept it as final. Poetry functions as a kind of dialectical image, where the past of struggles meets the present of defeat to produce a new understanding of the possibilities of emancipation. This poetic confrontation with loss doesn’t offer easy answers but insists on keeping open the question of the possibility of another reality, beyond the constraints of the existing order of things.

Fellow travelers on this melancholic journey are Tasos Sagris, whose wounds remain open and unexplored, offering a poetic contemplation on neoliberal alienation and social cannibalism, posing questions about the present and future, seeking moments of uprising and escape routes, meticulously recording the collapse of a society – the sound of endless metropolitan pressure. Sotiris Lykourgiotis with the power of knowing History that explains our civilization, relationships, cause and effect. Katerina Zisaki describing the yearning, the pain, the personal impasse with no exit; Poppi Delta in a perpetual search for an indefinable hidden happiness, explores in the ruins of defeat for traces of new possibility. Vasso Christodoulou who in her verses captures the weight of silence and the unbearable lightness of absence, documenting love as a revolutionary act and Dimitris Gioulos who crosses the boundaries between personal and political in pursuit of a new language for loss.

Where does the writer meet the actor in your work? Would you say that acting and writing are communicating vessels?

In reality, my theatrical performances with the Institute of Experimental Arts – Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” Sarah Kane’s “4.48 Psychosis,” Jean Genet’s “The Maids,” D. Dimitriadis’s “I’m Dying as a Country” and others – served poetry. My poetry and short stories have a strong performative quality; they’re almost like screenplays for films. Astrophysics and quantum mechanics taught me to analyze the world in depth, not to stay on the surface of things. I don’t feel like I’m dealing with different means of expression; I think I’m using different ways to serve Art.

The intersection of acting and writing in my work creates an alchemy where body and word become one. As an actress, I inhabit characters through physical presence and voice; as a poet, I channel these same energies into language. Both arts demand a deep surrender to desire and truth-telling.

On stage, I explore how a theatrical play carries stories and transforms them into living moments. through the body, the voice and the expressive tools of theatrical action. This physical understanding of how emotion moves through space directly influences my writing process. The stage taught me that truth isn’t just intellectual – it lives in our bones, our breath, our blood. When I write, these embodied experiences flow onto the page.

Both acting and poetry require a willingness to expose oneself, to become vulnerable in the pursuit of authentic expression. In performance, I learn how silence can speak as powerfully as words; in poetry, I bring this awareness of rhythm and pause to my lines. The theatrical understanding of timing and presence infuses my writing with a physical urgency.

There’s a profound connection between inhabiting a character on stage and channeling voices through poetry. Both demand we step outside ourselves while paradoxically diving deeper into our own truth. When I perform, I’m both present and transformed; when I write, this same duality exists – I’m simultaneously myself and something larger, channeling experiences that transcend personal boundaries.

Acting and writing are indeed communicating vessels – each art form enriches the other. The physical discipline of performance brings precision to my writing, while poetic sensitivity deepens my understanding of character and dramatic truth. Together, they create a complete language for exploring human desire and consciousness.

Your work lies at the border between poetry, performance, prose, investigating the connections between language, voice, body and place. Could this combination of dramaturgy and narrative be a way to bridge the gap between the writer and the reader?

The performative aspect of writing, when merged with narrative and poetic elements, breaks down the artificial barriers between different forms of expression. This synthesis reflects how real life refuses to be neatly categorized – our experiences are simultaneously physical, emotional, and intellectual. When we bring dramaturgy into narrative, we’re not just telling stories; we’re creating spaces for collective experience that challenge the individualistic focus of contemporary society. The combination of theatrical embodiment, poetic language, and narrative prose creates a space where both writer and reader can meet outside the conventional market-driven relationship of producer and consumer. This artistic convergence becomes a form of resistance against the neoliberal imperative to specialize and compartmentalize.

This approach allows us to explore trauma, resistance, and liberation in ways that engage the whole person – not just the mind, but the body and spirit as well. It’s a rejection of the patriarchal separation of reason from emotion, of mind from body, of art from politics. Through this integration, we can begin to imagine and create new forms of communication that aren’t mediated by market forces or hierarchical power structures.

My participation in the Institute of Experimental Arts and my long-term collaboration with Void Network has created a broad expressive palette, which includes hundreds of artists. The co-creation of artistic events in Greece and many other countries reveals not only the public’s need to connect with creation free from the laws of the art industry but also artists’ need to meet in fields of free expression, synergy, mutual aid, and mutual inspiration. The success of these actions by these two cultural organizations is based not only on multi-expressiveness but mainly on sincerity.

The poetic element in my literature opens up the possibility for readers to look beyond the surface of things, behind stereotypes, into the hidden sides of our logic. Reality is too complex to be captured realistically. My theatrical performances with the Institute of Experimental Arts – Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” Sarah Kane’s “4.48 Psychosis,” Jean Genet’s “The Maids,” D. Dimitriadis’s “I’m Dying as a Country” and others – have significantly influenced both my literary style and my poetic way of writing.

“Metamorphosis” director Tasos Sagris helped the entire cast reflect deeply on issues of patriarchy, social exclusion, and labor exploitation. Everyone around us feels the need for contemporary artistic works that will meaningfully resonate with our fears and anxieties. My experiences, travels, love, friendship, and self-cultivation form a vehicle of vocabulary and a perspective on life that evolves each time into a final creative work in various fields.

This multidisciplinary approach creates a direct emotional connection with the audience, whether they’re readers, viewers, or listeners. It’s not about using different means of expression; rather, it’s about using different ways to serve Art and the people around us, creating authentic connections that transcend traditional artistic boundaries.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS