Dimitris Mamaloukas (1968) was born and lives in Athens. He is a writer and a translator. He has written nineteen novels, eleven for adults and eight for children, short stories, articles and two plays. Among them, the crime novels The great death of Votanikos (translated into Italian as Dracme di Sangue), The abduction of the publisher, The lost library of Demetrios Mostra [shortlisted for the 2007 EKEBI – ERT Readers’ Prize], The loneliness of the road, as well as the novels A girl called Fini (translated into Turkish) and Hold my hand. His first book As long as there is alcohol there is hope, was adapted for the big screen and his short stories have been included in several anthologies. His crime novel The hidden cell of the Red Brigades won the 2016 Best Novel Award of the literary magazine O Anagnostis and was translated into Turkish. His novel Kill like Stephen King was published in Italian (Uccidere alla Stephen King) and will come out in Turkish within 2025. His latest book The strange Christmas of Mr. Sherriman was published by Monocle.

© Orestis Karlis

Your latest writing venture Τα παράξενα Χριστούγεννα του κυρίου Σέριμαν [The strange Christmas of Mr. Sherriman] was recently published by Monocle. Tell us a few things about the book.

It is an existential book that flirts with the supernatural. Mr. Sherriman is a man who lives a colorless life and a routine with which he is perfectly content. Until one day an unusual young man, Pascar, announces something to him that will turn Mr. Sheriman’s life upside down forever. Pascar will announce that he has been selected to be a chosen one. He is given the gift (or an unbearable task?) of being able to save a life, someone, anyone, that has just been lost. And the price of this act is that Mr. Sherriman himself will die soon after.

“Life is after all the fear of death and its counterweight: the hope that burns to the end, that dies last.” How is this emotional balance and all the underlying dilemmas depicted in the book?

Mr. Sherriman quickly realizes that the gift he has been given is not easy to handle. His life is turned upside down; of course, he doesn’t want to die, but he feels that he was chosen for a reason and slowly he begins to see the world in a different perspective. He discovers that until his encounter with Pascar he didn’t know how to live well. He didn’t know how to appreciate every moment or the health he enjoyed until then. For several days he wavers and doesn’t know how to move on. So, he slowly realizes that he has been permanently cut off from his previous life and the routine he loved so much. His long walks will lead him first to a hospital and then to a paediatric oncology unit. And there he will meet little Madeleine. And at last his life will make sense and his dilemmas will end.

How did your involvement with crime fiction begin? What remains your driving force decades later?

When I was seventeen I started reading literature avidly. At eighteen I seriously fell in love with crime fiction, a time which coincided with the greats of the genre being published in refined editions with a full bibliography and professional translation by Andreas Apostolidis. This love simmered inside me (I read countless crime novels) until I was thirty-five when my first crime novel, Ο Μεγάλος Θάνατος του Βοτανικού [The great death of Votanikos] came out. It turned out so good that I too thought I should pursue this genre. And since then I’ve had six more crime novels. Along with children’s and existential books.

Today, I continue to write my books in obedience to an irresistible inner instinct. I don’t know which one will be next, whether it will be a detective story or an existential one. With each passing day, instead of feeling tired, I feel that this was my mission on earth: to write my books. Fortunately, more and more readers are enjoying my work, even outside the borders of my country. It is a great satisfaction to be recognized.

What has changed and what has remained the same in these more than 25 years since the publication of your first book? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

I now have more confidence in myself. I know my worth and I don’t need any reassurance. In the early years you’re a bit like a ship without a compass, you’re going, but you don’t know where exactly to or if it’s worth the journey. I also know now how to recognize envy; I could never understand it of course, and I am happy inside with what I have achieved. Even the process of writing has changed, it has become easier, a task I have learned the tricks and secrets of. What has stayed the same? The longing when your book comes out. You love and care about it the same.

Of course there are writing obsessions, my books are full of my obsessions. The confinement of the heroes in various claustrophobic places. Bibliophilia in many variations: lost copies, rare editions, lost collections. The unusual heroes who are all hiding something. And then: expensive watches, rare and luxurious cars. Italy also features prominently in many of my books.

Since the mid-1980 there has been a revival of crime and noir novels in Greece. How is this trend to be explained? Does crime fiction also constitute a way to talk about contemporary social issues?

Crime fiction in Greece found its way after 2000, with a new generation of writers, including myself, that wanted to serve the genre by breaking away from the heavy legacy of Yannis Maris, who for better or worse limited it. A new generation that dared to set their books in foreign countries and admit that their influences were from French or American crime writers. To some “critics” this caused a shudder of horror, but sooner or later Greek crime fiction had to establish an international, contemporary, I should stress that, presence. At the same time many crime stories highlighted social problems (racism, xenophobia, trafficking, poverty). Perhaps some people wrote crime fiction having as their first priority to bring social problems to the spotlight. I am not one of them. But in every crime story I write, society and its problems are in the background.

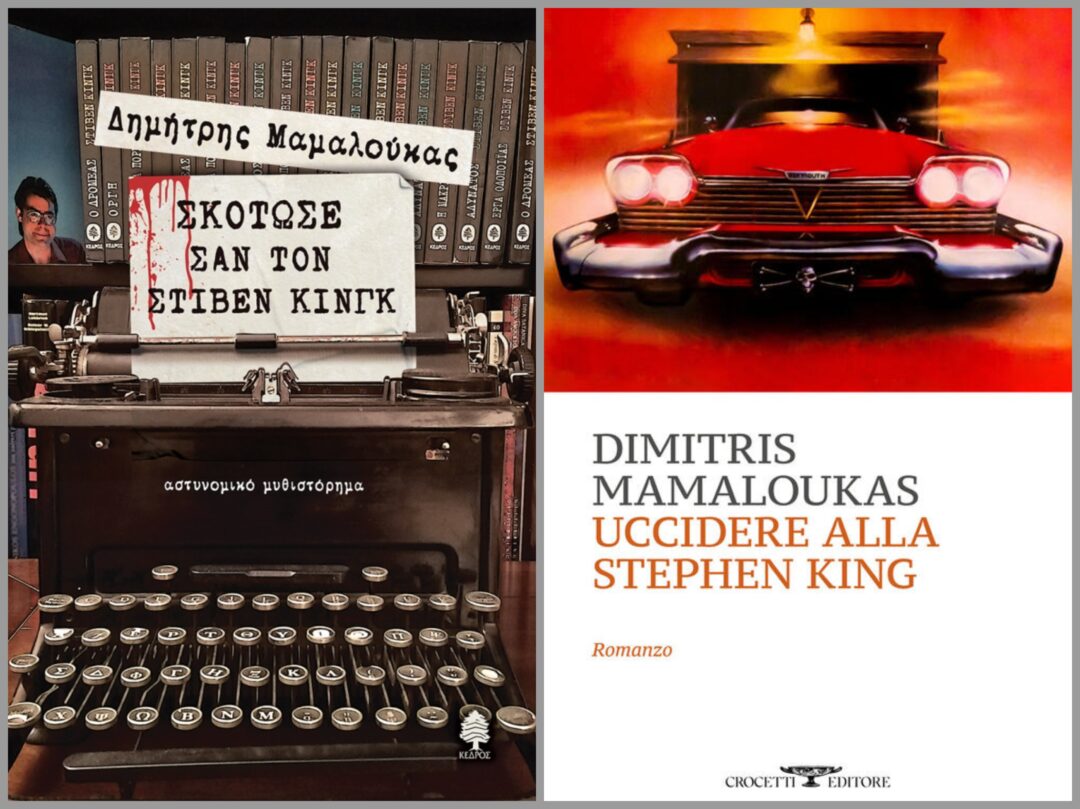

Your book Σκότωσε σαν τον Στίβεν Κινγκ [Kill like Stephen King] was recently published in Italian. How was the book approached by Italian readers?

I would say that it was met with disbelief at first, but it was then quite well received. Anyone who knows of King greatly appreciates the book, recognizing in him the admirer and, most likely, collector of King. King is even more famous in Italy than in Greece and many books have been written about him, mostly essays; so, a novel was a bit of a turn-off.

In the chapters of my book I gave titles of short stories and novels by King. Some thought I wanted to steal King’s glory (I reminded them that I’ve written nineteen books) or that I didn’t know how to put my own titles in my chapters. Whereas what I wanted to show (and find out at the same time) was whether a King title would fit in the case I was making, in my chapters. I had said to myself that if I couldn’t find enough titles I would give up on the project. But they were found. And this is proof that King has written about everything. The book is very close to having an international career as it will be released in Turkish in 2025. Turkey is a country that seems to suit me as three of my novels have been translated and I have a fanatic readership there.

Does contemporary Greek literature have the potential to move beyond national borders and attract foreign readers?

Definitely so, as long as there is state support for translations. Authors are essentially fighting on our own to get a book translated into a foreign language. I feel proud that five of my books are published in foreign countries solely through my own efforts and those of friends. I believe that several books of Greek crime fiction, and Greek literature in general, deserve to be published abroad.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

**Intro Photo by Antonis Tsokos

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE