Greek art before the Munich School

Ancient Greece is universally considered a cradle of the arts – but, in modern times, arts in Greece were not truly developed until as late as the 19th century. During the intellectually and culturally vibrant times of the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment (and while the spirit of Ancient Greece was a primary source of inspiration in the arts, letters and sciences), Greece was virtually cut off from the rest of the Western world.

Under Ottoman rule, Greece was made up of small rural communities, with people almost exclusively working in agriculture, maritime occupations and commerce, while many were striving financially. The lack of large urban centers and of any form of organized educational institutions led to an almost complete decline of the arts, while at the same time the absence of an organized state and infrastructures led to local isolationism and the subsequent absence of a unified national identity.

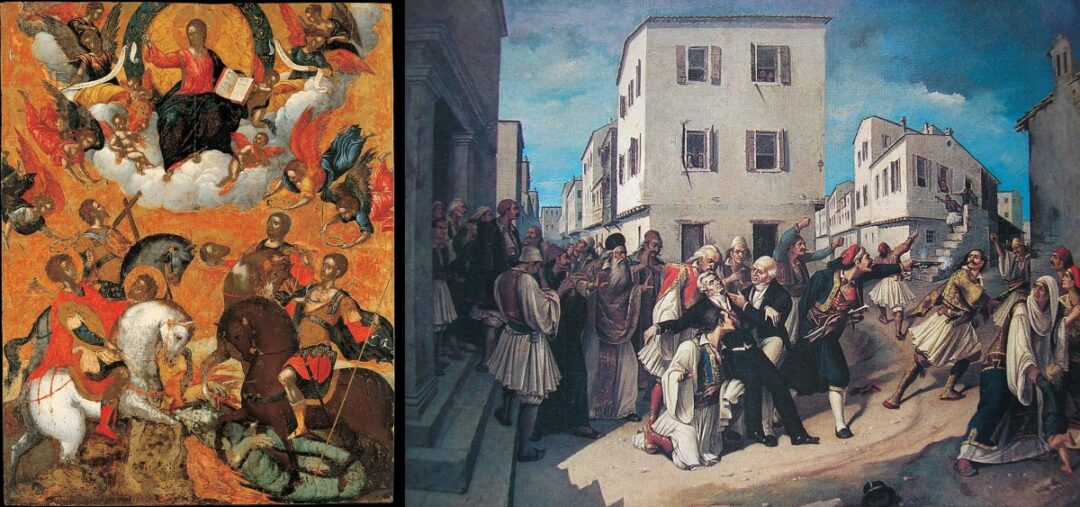

In these circumstances, art -and especially secular art- could not flourish. Iconographers, painting in the post-Byzantine style, still worked, illuminating churches and monasteries. Western art had influenced iconography in parts of Greece that were not under Ottoman rule, especially Crete during the 15th through the 17th century as well as the Ionian Islands, which were overseas possessions of the Republic of Venice. However, the Cretan and the Ionian School still fell under the umbrella of post-Byzantine painting, consisting predominantly of religious works (although portraits and some historic and genre scenes can also be found in the latter), and reached a rather limited audience.

The birth of the Munich School

With the birth of the modern Greek State, and as a national identity was being forged, the concept of “Greek art” was also gradually formed. 1837 saw the founding of a School of Arts, initially focusing on architecture; a graduate school for Fine Arts was established as a department of that institution in 1843, evolving into the Athens School of Fine Arts.

However, anyone with a remarkable talent aspiring to an illustrious career in the arts would pursue further academic training abroad. One of the most common destinations was, understandably, Paris, as a beacon of culture, given also that French was a language widely spoken by the higher classes of society.

Nevertheless, some important factors led to Munich becoming the primary destination for Greek art students at the time; the main and foremost of these reasons was the fact that Greece had formed a special bond with Bavaria and its capital city, since its first king, Otto, came from the Bavarian dynasty of Wittelsbach. Hence, the Greek state actually provided several scholarships to exceptional art students who wanted to continue their studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

Besides, in the second half of the 19th century, Munich was an important center for the visual arts, especially painting. In Germany, “the Munich School” signified a group of painters who trained there and, in many cases, also taught at the Academy, becoming the teachers of the artists that would soon form the Greek iteration of “the Munich School”.

It is worth noting that, under King Ludwig I (father of the King of Greece, Otto), who was a lover of Ancient Greece and a patron of the arts, many grand neoclassical edifices were built in Munich, including museums filled with antiquities and international masterpieces. For that, the city was dubbed “Athens-on-Isar”. That same neoclassical style permeated the design of most public buildings and private mansions in the Greek capital. All this added to the close ties between the two cities at the time, with Bavaria being inspired by Greece’s glorious past, and the Bavarian administration trying to forge the national and cultural identity of the nascent Greek state on that same basis.

Main features

The German Munich school was the most important trend in academic painting in Germany at the time, gaining fame throughout Europe. It was characterized by a naturalistic style, moving away from the Romanticism of early 19th century, and artists depicted primarily history scenes, but also genre scenes, landscapes and portraits.

The style of painting found in the works of the Greek Munich School can best be described as academic realism; people and objects are rendered with naturalistic detail, with artists trying to capture the expressions of the people portrayed and convey their emotions. The balance of light and shadows was also important, with a liberal use of chiaroscuro by most artists. Typical subjects, again, included landscapes, portraits, genre, still-life, and history painting.

Genre painting is particularly associated with the Munich School, especially in Greece, where it was also known as ropographia (“depiction of trivial things”), but predominantly referred to as ethographia (literally “study of mores”), a term borrowed from Greek literary criticism. Subjects are drawn from everyday life, especially in a rural context, with people depicted doing everyday chores, working the land, feasting etc. Seventeenth-century Dutch art and German Biedermeier painting have also been suggested as important influences on Greek genre painting, especially due to their similarities in themes and iconography.

History painting, on the other hand, naturally drew primarily from Greece’s recent history, i.e. the heroes and battles of the Greek War of Independence, which had led to Greece breaking away from the Ottoman Empire and becoming a free country.

Important artists

Among the main representatives of the school, those that have gained the greatest renown are Nikephoros Lytras (1832 – 1904), Nikolaos Gyzis (1842 – 1901), Georgios Iakovidis (1853 – 1932) and Konstantinos Volanakis (1837 – 1907). In fact, these painters were widely recognized outside the confines of the Greek state, and are considered masters of the original Munich School, and not just its Greek counterpart.

Lytras and Gyzis were the most important genre painters in Greece, Iakovidis excelled in portraiture and the depiction of children, while Volanakis’ seascapes and use of light set him apart from the rest of the group. All of them became important teachers at the Athens School of Fine Arts, except Gyzis who actually became a professor at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and mostly lived abroad.

Other important painters include Theodoros Vryzakis (1814/19 – 1878), famous for his depictions of war scenes from the Greek Revolution, Polychronis Lembesis (1848 – 1913), a genre painter, Nikolaos Vokos (1854 – 1902), known for his still lifes, Ioannis Zacharias (c. 1845 – c. 1873), Epameinondas Thomopoulos (1878 – 1976), Ioannis Koutsis (1860 − 1953), Stylianos Miliadis (1881 − 1965), Nicolaus Davis (1883 – 1967) and Nikolaos Alektoridis (1874 – 1909).

Although the school’s influence can be seen in the works of early 20th century painters such as Spyridon Vikatos (1878 – 1960) and Thalia Flora-Karavia (1871–1960), the influences of Impressionism and, especially, Expressionism and Symbolism on Greek painting would signal the end of the movement at the start of the 20th century. Today, works from the Munich School can be found in museums and private collections in Greece and the rest of Europe. The most comprehensive collection can be viewed at the National Gallery of Athens.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Nikolaos Gyzis, the Greek master of genre painting; Nikephoros Lytras, the Artist behind Greek Christmas’ Most Celebrated Painting; Georgios Iakovidis, a painter of childhood; Theodoros Vryzakis, the “painter of the Greek Revolution”; Konstantinos Volanakis and his superb marine world; Discover the National Gallery of Athens

N.M. (Intro image: Georgios Iakovidis, Children`s concert, 1900 [National Gallery of Athens])