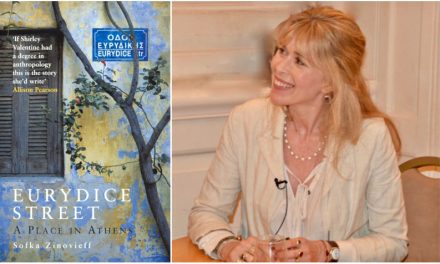

Jennifer R. Kellogg is a literary translator from Modern Greek and holds a PhD in Modern Languages and Literatures from the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). In 2019 she was an Emerging Translator Mentee of the American Literary Translators Association. She was awarded the 2024 Elizabeth Constantinides Memorial Translation Prize for her translation of Book of Exercises II by George Seferis.

How did your involvement with Greek language and literature begin?

I studied Classical Philology in college and came to Athens in 1996 for a year at College Year in Athens. It was the pre-internet era and I learned to speak Modern Greek outside of the classroom, through every day interactions in Athens. At the same time, I had the privilege of studying with some of the great scholars and teachers of that era— Tessa Dinsmoor, Nanno Marinatos, Mimika Dimitra, and Thanos Veremis among others. In Veremis’s class on Modern Greek History and Politics, I learned about the Asia Minor Catastrophe, a historical event that was new to me. The traumatic destruction of Asia Minor Hellenism and the Exchange of Populations were absolutely shocking and became my obsessions and scholarly interests for years after that.

At the same time, I was introduced to Seferis in literature class. I immediately began reading and writing about his poetry, to myself mostly. I left Greece in 1997 resolved to continue my exploration of my three preoccupations: the Catastrophe and its refugee crisis, and Seferis. I then spent years perfecting my Modern Greek and studying for a Masters and PhD; my Masters thesis was about Pontian Hellenism in America and my PhD dissertation was about the notion of a lost homeland in Seferis’s poetry.

You were recently awarded with the 2024 Elizabeth Constantinides Memorial Translation Prize for your translation of Book of Exercises II by George Seferis. Tell us a few things about the book.

This book was always set apart from Seferis’s Collected Poems because it contains political, satiric, erotic, humorous, and experimental poetry. It was published after Seferis’s death, so it has the air of “what was left unpublished.” Yet Seferis himself first edited and collected most of the poems in this book, just after he retired from serving as Ambassador to the United Kingdom, when presumably he felt released from his diplomatic restraints. Before he could finish the manuscript, he was nominated for and awarded the Nobel Prize, an honor that demanded resuming the restraints of the national statesman and literary hero. After the Nobel, Seferis became seriously ill, the Colonels seized power, literature was suppressed, and then Seferis passed away without completing this book. It was published in 1976 with George Savidis’s editorial work.

Most of the poems in Book of Exercises II are specific to a particular time and place in Seferis’s diplomatic career; these poems explore experiences rather than ideas. There are a few interesting drafts from Mythistorema and Thrush that reveal parts of the poet’s creative process. The book is full of humor, irony, bitter satire, and moments of erotic play. There are a lot of emotions and opinions that couldn’t be revealed in other contexts, such as the crushing anguish of living abroad during World War II and the Greek Civil war, a time when so many Greeks perished.

Which were the major challenges you were faced with while translating Seferis?

Before I started on Book of Exercises II, I spent ten years working on my dissertation, where I wrote about Seferis’s poetry and made my own translations. This was a long process of perfecting my “Seferis voice,” or rendering in English the qualities of the voice I heard in Greek when I read Seferis. I looked at words, language patterns, symbols, and images that Seferis used often and came up with my own consistent way of rendering them. I wanted to inhabit the spirit of Seferis within myself, like an actor playing a character, rather than considering each poem its own essence. My translations of Seferis’s poems for my dissertation were private, part of my apprenticeship and learning.

Book of Exercises II offered more challenges on top of perfecting my “Seferis voice,” because in this volume Seferis himself played with voices, characters, and literary translation. Seferis was fluent in English and loved the British tradition of limericks. There are many satiric rhyming poems in Book of Exercises II, as well as imitations of Late Antique literature, mantinades, Kalvos, and T.S. Eliot. There were layers of idiomatic speech and style in the Greek originals that required skill to bring into English. I did my best to adapt my “Seferis voice” into rhyming satire in English.

“May [Seferis’s poetry] remind us that questions of migration, identity, and belonging are perennial and universal, and that self-expression, especially humor, is an adaptive way to cope with trauma, violence and grief,” you write in your introductory note. What is that makes Seferis’s poetry both timeless and timely, as well as appealing to an English-speaking audience?

Many people remember Seferis’s poetry for years without regularly engaging with it.

His voice always throbs with an unfulfilled longing and a sadness that readers recognize within themselves, even if at times the images, references, or context of the poems seem mystifying. His poetry leaves the reader with that unfulfilled longing, which pulls the reader back to the poems to repeat the experience.

There is also the quality of prophecy in Seferis’s work: he is narrating a future—based on the past— which he is powerless to change, despite being one of the few people with the power to be present at key historical moments. His poetry speaks to the way that memory works within us: fragmented, ripe with emotions and details, seemingly present, but inaccessible.

It also must be said that Seferis represents twentieth century Greece in many people’s minds. We non-Greeks also engage in longing for a non-existent Greece, where mythical shadows walk among us in quaint traditional villages, boats ply the beautiful Aegean, and we are enchanted by Greek poetry. Seferis is the Greek national poet par excellence: with him, we recognize that we are all entangled together in the beauty and sadness of the Greek National Myth.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

Language is malleable, not static nor monolithic. It takes on meaning in the mind space of every reader, in a way that is unique to each individual and their personal experiences and perceptions. Language is also the record of a collective agreement to communicate in a particular way that confers cultural belonging.

Translation is an act of valuing and celebrating both the universal and particular beauty of a specific language and work of art. In many ways, it is impossible to remain faithful to the original language when translating into another. Literary translation assumes that the intention and creative work of a writer has value, even when recreated in another language and imbued with that language’s own cultural context and history.

The role of the translator is to trust that the creative act of bringing the original work into a new linguistic and cultural landscape is possible. Without that belief, literary translation becomes mechanical and utilitarian. The “utility” of literary translation is creativity, expansion, and compassion for other people and cultures.

Perhaps an “unethical translation” is one that privilege’s the translator’s personal agenda, rather than the artistic and transformational power of the work of art he is translating.

Could translators act as cultural ambassadors fostering deeper understanding between cultures and nations?

Yes, I think this happens naturally, as translators promote their literary translations. They act as advocates for the languages, cultures or sub-cultures, identities, and points-of-view of their authors and creations.

Translations invite readers into cultural landscapes of the mind, which allows for deeper internalization of others’ realities as well as the history and characteristics of another place or time. With translation, the great literary texts of one culture can be accessible in another. Yet, once a work is translated into a particular language, it isn’t ever permanently finished or “done.” I believe that there is always room for re-translation to introduce a new generation to a particular work, given that language changes rapidly through the generations.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read more: Book of the Month: “Book of Exercises II” by George Seferis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE