Antoine Cassar is a Maltese author and translator, with roots in activism for universal freedom of movement and other causes. He writes in Maltese, English, and Twanniż (a mix of both with Italian, intermediate Greek and other tongues), mostly about maps and islands, language and music. Forty Days (Ede, 2017), a book-length poem on walking as therapy, was awarded the Malta National Book Prize, and shortlisted for the European Poetry of Freedom award. Passaport (2009), printed in the form of an anti-passport for all peoples and all landscapes, has been published in over a dozen languages; adapted for the stage by theatre groups in France, Belgium and Canada; and set to music in France, Italy and Australia. Proceeds from the sale of the booklet are donated to grassroots associations supporting refugees in the community.

How did a Maltese poet, editor and translator choose a small village in Ithaca to create Biblioteca Francesco?

I disembarked in Itháki at the end of the first covid summer, by accident, and by magic. It wasn’t Homer’s epic that led me here, but my own painful, crazy odyssey. Not shipwreck, but earwreck.

Long winding story short, I was stuck in Luxembourg, where I worked as a translator for twelve years. As happened to many of us, lockdown brought ancient traumas to the surface, manifested in my case by the onset of hyperacusis. The phone and tablet speakers, rustling plastic or paper, water on the boil – simple everyday sounds began to hurt. Not to mention noise from the road, and the nearby cargo runway. When the borders opened, I didn’t think twice. I put a few clothes, books, and my three-month-old kitten Don Pablo in the car, and left. I couldn’t drive home to Malta – I have a highly vulnerable close family member and they instructed me to stay away –, and so, lost and depressed, I ventured haphazardly south, mostly at night when the roads were quiet.

Two months later, at a strange crossroads in a seaside town in western Greece, my ears finally broke. Every motorbike, every starting car, the tv of a kafeineío were suddenly twenty, thirty times louder. I desperately needed an island. I went to the beach and looked at the map. Several Ionian islands to choose from. Don Pablo was drinking from his white paper bowl, and somehow it capsized. The water stain on the ground drew a shape very similar to Itháki, with its isthmus and peninsulas. Bravo, Pablito. Three stormy days later we crossed to Vathy, and three days after that, a magical encounter orchestrated by Don Pablo led us to our final destination, Exogí. Out of this land. Population, six (today four).

We stayed in Exogí for two years. I bought a little ruin in Limourata, the hamlet on the path below Exogí, and began renovating it into a library house. But I was too depressed to make much progress. When my ears healed, I finally returned to Malta. After a year working there as a book editor, my mother, best friend and last grandparent died in quick succession, and the earache came back with a vengeance. My own village, Qrendi, became too dangerous, not only due to the noise. Luckily I had a refuge to go to, half-ready. It was for sale, so I bought it from myself for one koukouvágia (€1). I’ve been here since July, and I will stay. With Don Pablo, and Rokku, my deaf-mute peimenikó dog from Samos. No traffic, no neighbours next door (except in summer), nothing but goats, an owl, rain filling the sterna, the trees and Afáles Bay when it’s windy. Only a three-minute walk from the road, where I park the bibliomobile.

As you describe it, Biblioteca Francesco is “a Mediterranean library on Homer’s path, in Limourata, Ithaca”. Can you tell us more about this venture of yours?

It has long been my dream to open a library close to the sea, with a little shop selling books and literary souvenirs. I can no longer do so in Qrendi – too loud, too expensive, and in any case, in Malta there is no whistleblower protection (another long story), so I won’t be visiting home for some time. But I’m in the right place, not only for health-related reasons.

Mediterranean, opposed in some way to European, a term which tends to favour the north. That doesn’t exclude Joyce, Hesse, Dostoevsky from the library, let alone authors from other continents! Francesco, after my Nannu Frank, the only other bibliophile in the family, who like me suffered from hyperacusis. He used to read to me in French (he grew up in Montpellier, and returned to Malta after spending WW2 in hiding), to soothe his ears and my depression. Saint-Exupéry, Rimbaud, Maupassant. Memories I had been brainwashed to forget, from the age of 11, due to family wars. When I saw him again in my mid-20s, it was too late, deafness and dementia had taken hold, flow in conversation was impossible. He passed away in 2015. During the first lockdown, it took me a while to realise that my new hypersensitivity to noise was a physical, atavic manifestation of that particular trauma. One evening, a distant friend recounted her childhood memories of her giagiá (‘grandmother’ in Greek) reading to her in French, and the recollections all came flooding back. At the age of 42, I finally started to feel my nannu’s presence again. Today, I try to live the creative life that he could not.

Homer’s School is a twenty-minute walk away, down the path through the forest. In the summer months, tourist pilgrims following the trail pass by my house. They will be welcome for a refreshment, to rest or swing on the avlí (‘courtyard’ in Greek) looking out to Afáles and the Akarnanía mountains, and to borrow a book for the remainder of their stay on the island. But the library caters mostly for the north Itháki locals, who have been borrowing books since September.

What kind of books can readers find in Biblioteca Francesco?

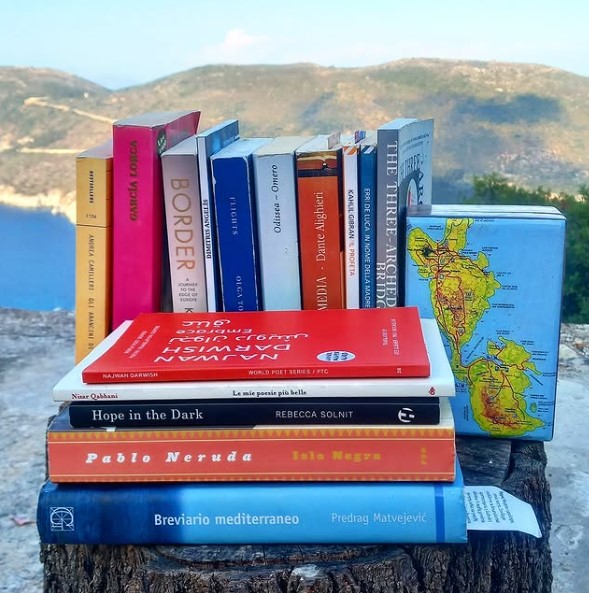

We have books in many genres – particularly novels, poetry, children’s literature, geography –, and in several languages. Greek, Italian, French, Spanish, English of course, Albanian, Turkish and more. Some books were my own, many were bought or found on my travels, others were donated by friends and former colleagues. I’m always on the lookout for books, second-hand especially. I would like to expand the music, philosophy, graphic novel, and football sections. One day I’ll collect my books from Malta, including the old French ones inherited from my nannu.

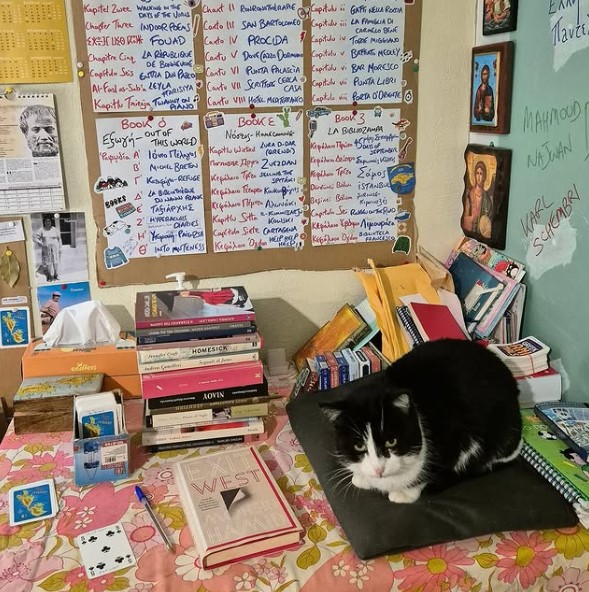

Dewey classification didn’t seem to make much sense for a non-academic library, so I use the BibFran-ΒιβΦραγ system. Each ‘tmíma’ and language are denoted by a Greek letter (ζ for pezografía, ε for elliniká ktp.), followed by Latin letters for the author initials, and a sequential number. This makes book cataloguing so much more fun and interesting. Don Pablo, who likes to spend hours sitting on the desk, has become a cataloguing expert. Rokku takes care of the hospitality side, surveys the valley and monopáti (‘trail’ in Greek), and – despite being deaf – approves the newly arrived comics I read to him. He’s not too keen on Spiderman or Disney, but he adores Corto Maltese, Popeye, and of course Rantanplan.

Which are the challenges you are faced with while compiling the library?

Carrying kaláthia (‘baskets’ in Greek) full of books down or up the monopáti, the equivalent of twelve flights of stairs! But this keeps me fit, and the colours are different every day. When the path is blocked by goats or sheep, ypomoní (‘patience’ in Greek), but that only happens once a month.

Sourcing books isn’t a problem, I have a mailbox at the post office and I’m never in a rush for packages to arrive by sea. The biggest challenge is perhaps encouraging more residents of Odysseus’ island to find a book and read. There is only one (decent) bookshop in town, which draws most of its income from photocopies and selling toys. Most of the population work in tourism, and it pains me to see how their life revolves around improving their product, then slogging non-stop from Monday to Sunday for seven or eight months. This is what Itháki has been reduced to by consumerism and economic bullying – a servant of the yachts, a waitress enhancing the northerners’ sacred holidays. “It’s sooo much cheaper than the UK!” Good for you. The girl you just said that to, with a masters or Phd, is working for minumum wage in order to save up for the winter. It’s little wonder many Thiakoí seem to have lost touch with the true spirit of the island.

Cavafy wrote that the journey to Ithaca is more important than the arrival. I disagree. It is better to be here, especially in the late autumn and winter. But the locals deserve a better quality of life, with more leisure time to read and chill.

What is that you find appealing in Greek literature? More generally, are Maltese people acquainted with Greek culture and vice versa, are there Maltese writers that have become known in Greece?

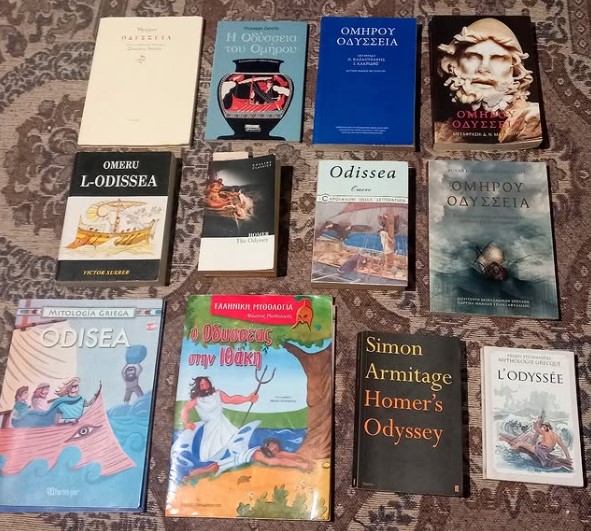

I’m still becoming acquainted with contemporary Greek poetry, but in what I’ve read so far, there is a certain economy and clarity of structure that I don’t find in other tongues. I recently began translating some poets into Maltese – Karagiorgi, Gkioulos, Pastakas and others –, and I look forward to exploring more. I’ve also co-translated some Seferis, Ritsos, Cavafy with a friend who used to work at the Maltese embassy in Athens. I adore Karyotakis– his sonnet to the piano, for example! –, and I closely relate to his story with Polydouri. But the book I’d most like to translate is the Odyssey. I’ve read it in several languages and adaptations, and when my passive Greek is good enough, I’ll try Kazantzakis’ version. Victor Xuereb’s rendering, in Maltese endekasillabi, is precise, but not very musical. First, however, I’d like to adapt the work for young Maltese readers. Calypso most likely lived on Gozo, Malta’s second island, and I’d like my youngest relatives to read about that in their own language. The biggest challenge, I imagine, will be deciding what details of the epic to leave out.

As far as I know, the only living Greek poet published in Maltese is Katerina Iliopoulou, in an anthology of the Inizjamed literature festival. Vakxikon have published three books of Maltese poetry in recent years – Immanuel Mifsud (a towering influence on my own writing), Elizabeth Grech, and an anthology of young poets. Unfortunately, despite the geographical proximity, cultural bridges between Malta and Greece have long been lost. That’s something I’d like to work on. Beyond yachts with Maltese flags of convenience, and the (interesting, nostalgic) experiences of Greek ship and dockyard workers in 1970s Valletta, the two countries see each other as little more than holiday destinations. They exoticise one another, as if peering down from the north rather than across their common sea.

What are your future plans?

First of all, grafeiokrateía (‘bureaucracy’ in Greek)! My brothers and I are slowly setting up the Fondazzjoni Francesco, starting with a small inheritance from our grandparents, and we’d like it to be active in both countries. Through the library and online, the foundation will seek to encourage reading and music as therapy, and raise awareness on ear conditions, societal noise and their effects on mental health.

Soon I’ll publish the first booklet by Ekdóseis Frangískos – Rokku’s Itháki Phrasebook. Followed by Don Pablo’s Library Handbook. After that, I’d like to specialise in bilingual books, of poetry and short stories. For that, I’m going to need Greek help.

The renovation and extension of the library should be ready by June, then I’ll start organising events – readings, games nights, concertini, outdoor film projections. I’m also planning an online audiolibrary, and podcast channels on books, translation, classical music, and other subjects by friends of mine, supported by the foundation. And later, starting some time next year, a monthly writer’s residence, for authors seeking a peaceful place to ruminate and work.

And how about a little poetry and piano festival on Homer’s mountain? So many possible venues around north Itháki. So many possibilities, provided I don’t let depression win again this time round. Rokku and Don Pablo won’t let that happen, and I know how to live with my ear condition now. ‘Ola tha páne kalá. Or as my Thiakí giagiá Dionysía says in her beautiful syntax, tha páne kalá óla. Sigá sigá (‘ Ιt’s gonna be all right, little by little’ in Greek).

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE