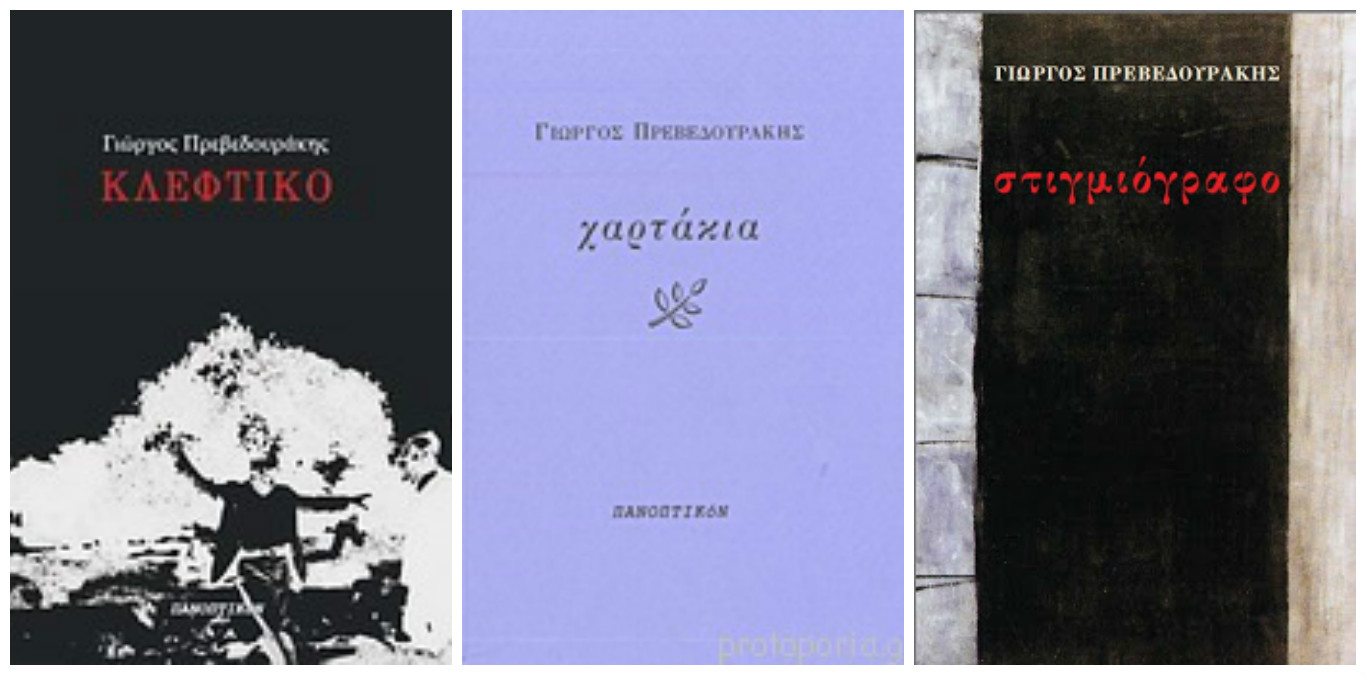

George Prevedourakis (1977) is the author of three collections of poems: Στιγμιόγραφο (Planodion ed., 2011), Κλέφτικο (Panoptikon ed., 2013) and Χαρτάκια (Panoptikon ed., 2016). He has also translated poems by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, which were included in the History of Clouds and other poems collection published last spring by Panoptikon Editions.

George Prevedourakis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest collection of poems, Χαρτάκια, ‘a series of untitled, brief fragments and meditations’ resembling ‘the ambiance and feeling of an empty room’. He comments on how the notion of time is imprinted on his work, noting that it has treated time as ‘the fleeing moment’ in his first collection, a ‘series of moments-incidents’ in his second and an ‘empty signifier’ in his third. He also talks about Kleftiko, a transcription of Howl by Allen Ginsberg, as well as his translation in Greek of Hans Magnus Enzensberger’ s poems and how he was fascinated by the latter’s ‘elegant, cosmopolitan wit, playful spirit and persevering, all-embracing social criticism’.

Asked about whether poetry can act as a political paradigm, he comments that “once we decide to communicate our writings we should do it foremost as readers-citizens and not as a bunch of uninformed, detached and uninterested, self-proclaimed priests of some obscure religion, that are in a state of privileged communication with God himself”, concluding that luckily, “our current psychological state, where despair and/or determined anger, fear, confusion and/or passive withdrawal are most probably the prevailing sentiments” is adequately represented by an abundant number of contemporary poets.

Your third collection of poems titled Χαρτάκια was recently published. Could you tell us a few things about the book?

With Χαρτάκια I wanted to produce a work that closely resembles the ambiance and feeling of an empty room. The book consists of a series of untitled, brief fragments and meditations, with the notion of time comprising the predominant axis around which these fragments revolve. I approached this material in the same way that one processes a long, yet interrupted synthesis. In other words, my aim was not to present a series of short poems that stand autonomously from one another —though some of them unintentionally do. My principal intention was to take the minimalist form to its extremities, to condense the already condensed, in a non-linear, abrupt manner, while also conveying an intact and coherent gesture to the reader. I don’t know if I have accomplished this rather ambitious goal, yet I have the impression (or perhaps the illusion) that with this small book my initial objective has been met. After all, it was the room I was interested in, not its decoration.

In his review, Antonis Psaltis wrote that “five years after capturing and recording the moment as the eternal imprint of the presence of time in ‘Στιγμιόγραφο’, the question in ‘Χαρτάκια’ seems to shift as to whether the current, inconceivable and increasing speed allows for integral moments”. How is time, in all its forms, imprinted in your work?

I suppose that time must have been a personal obsession of mine, even before I had the slightest desire for writing, let alone publishing, poetry. A somewhat commonplace obsession, I must admit, yet obsessions are to be followed and carried out meticulously, to the degree that one, literally, collapses upon them. In Στιγμιόγραφο (Planodion ed., 2011), as the title suggests, the main focus was placed upon the fleeing moment, trying to seize and depict the instantaneous within the instant, in an almost ‘photographical’ manner. In Kleftiko (Panoptikon ed. 2013), time is rather dispersed and extended, stretched out of its original proportions, engulfing a series of moments-incidents. Lastly, in Χαρτάκια, I’m treating time as an ‘empty signifier’. In reality though, it is time that treats me as such. A gesture of inadequate and futile retaliation had to take place, and, up until now, it has.

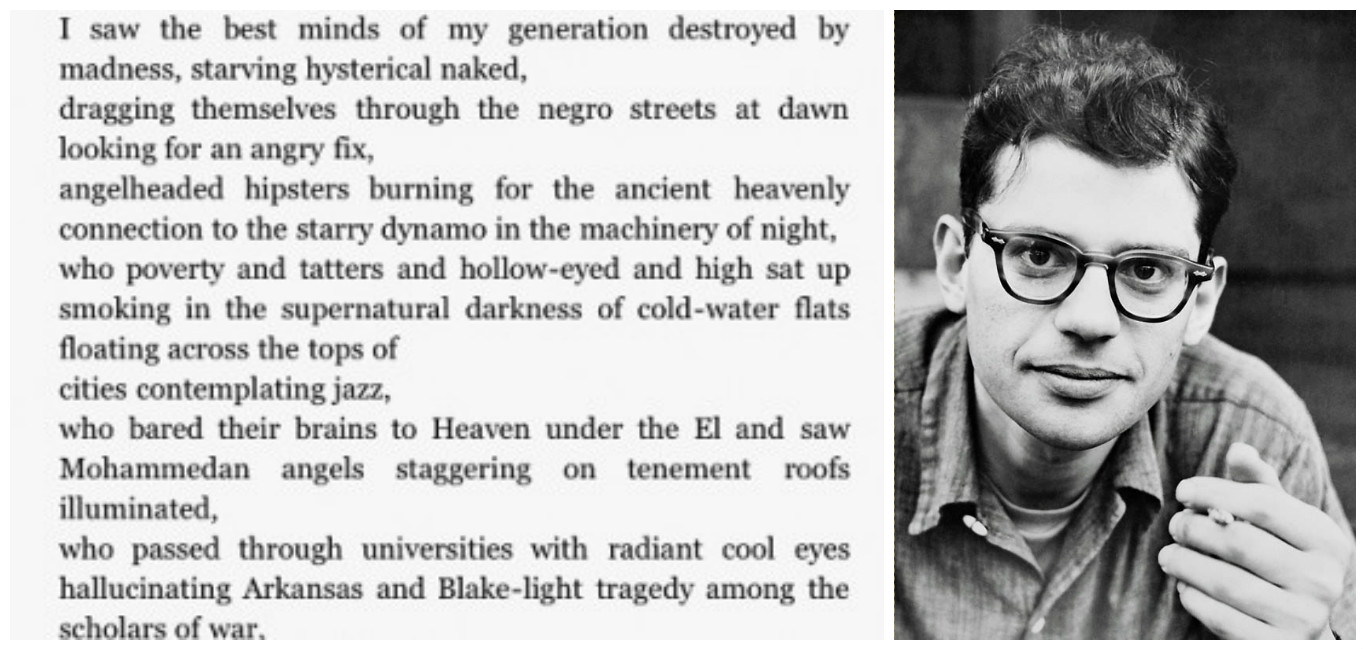

Your second collection of poems Kleftiko is a take on Allen Ginsberg’s Howl set in Greece amid the crisis. How was the title inspired? How does ‘kleftiko’ fit in the context of modern Greece?

The title was inspired instantaneously, as most things that get inspired usually do. I was looking for a three-syllable word that would directly lead the reader to ‘Ουρλιαχτό’ (the Greek translation of Howl) while also suggesting a series of other meanings, open to interpretation. For example, the title functions as a hint to the gesture of ‘μεταγραφή’ (transcription), given that I kindly yet unreservedly robbed poor old Ginsberg’s Howl (parts I+III), America and Aunt Rose framework, rhythm and form so that I could put into words my own, personal howling. In addition, Kleftiko is a part of the Greek folk music genre (indicative of the flamboyant, long-winded form and articulation of these particular poems). Kleftiko is also a traditional recipe for cooking lamb, but perhaps this is completely irrelevant.

In relative terms, Kleftiko has fitted quite comfortably within the context of modern Greece; it has been widely read, critically praised and/or refuted, while, to my surprise, it has interacted with other arts; theater, music and, lately, even film. One cannot complain.

Although I was never a devoted ‘fan’ of the great Allen Ginsberg, the idea of a meta-writing/transcription of Howl has been occupying my mind since the early 00s, when (according to some, at least) we were supposedly enjoying ‘the long summer of our content’. My points of reference, the imagery and the material which comprised the background and the basis of this book, derived rather from the sociopolitical setting of my puberty (i.e. the 90s) and not from the blurred, violent and disturbed scenery that we’ve become accustomed to calling ‘Greek crisis’. Hence, I would have written this book even if the entire issue of our current misfortunes had proven to be a major hoax, a flick played out for a short time, instead of the aggressively metastatic cancer it proved out to be.

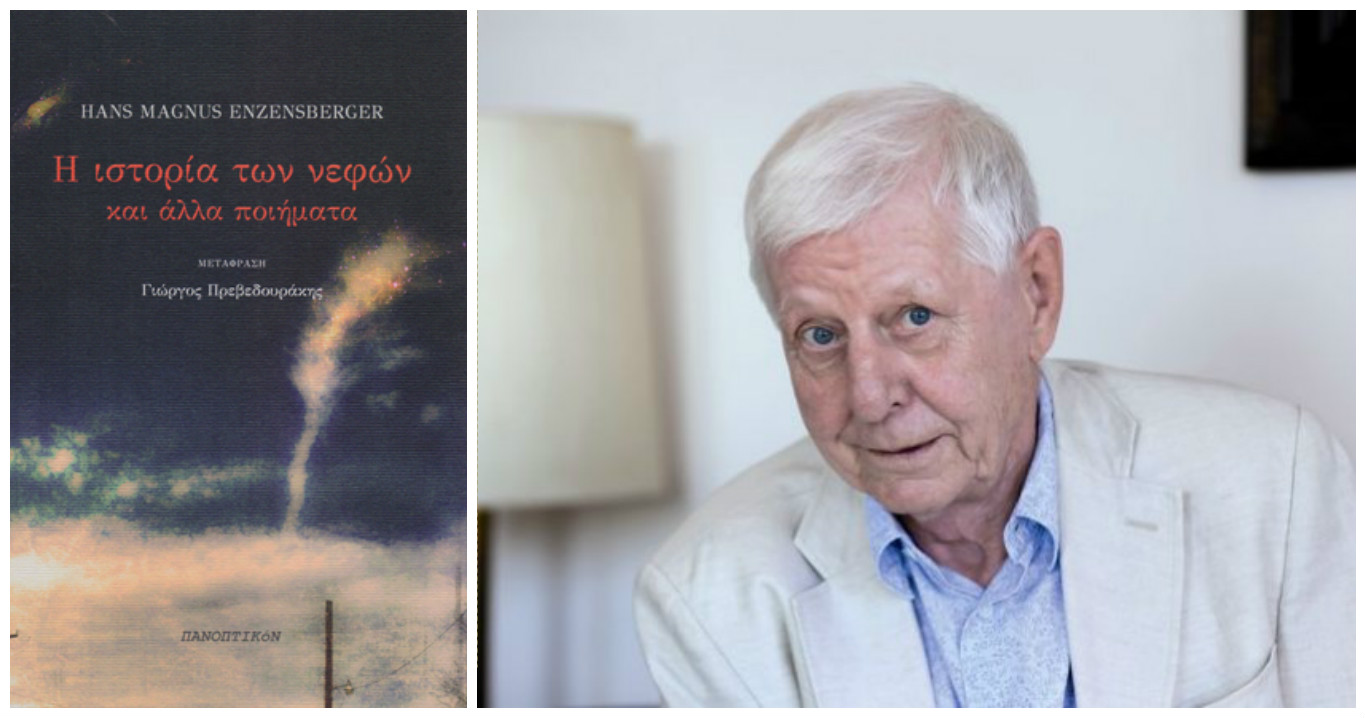

How challenging was it for you to translate Hans Magnus Enzensberger, one of the greatest living German poets?

Η.Μ.Enzensberger once stated that he is the “saboteur’ of his depression”. Having logged countless hours in exploring and translating his poetic work over the past 6 years (a work that spans the course of more than 7 decades) I could say that translating Enzensberger has become my own, highly effective antidepressant. Furthermore, as I am sure you know from your own experience, translation is a process that teaches humility and cultivates a dual sense of respect: you have to respect the writer but also the reader. In other words, there isn’t much room for your private experimentations, the borders and the setting cannot be twisted in accordance to your personal taste and beliefs. Additionally, a certain kind of mutual trust is gradually established between the poet and the translator. As commonplace as it may sound in the face of H.M. Enzensberger I have discovered a true friend and a faithful companion.

Having been acquainted with his works since my late teens, when I was a student in Britain, I was instantly fascinated by his elegant, cosmopolitan wit, playful spirit and persevering, all-embracing social criticism. I translated few of his Lighter than Air poems back then, more as an exercise, with no real intention in publishing these translations. It was almost ten years later (with his History of Clouds collection) that I began to steadily plunge into his work. To my surprise, I realized that his poetry has never been systematically translated into Greek, besides a wonderful translation of some of his younger works that was published way back in 1978, along with some scarce poems found in literary magazines and websites. I therefore chose to provide the reader with a detailed illustration of his works and not a “best-of” type of anthology. Enzensberger is a protean poet, constantly changing angles, methods and forms. As mentioned above, I had to respect and pay dues to my ‘friendship’.

History of Clouds and other poems was hence published last spring by Panoptikon editions and it includes 109 poems from 4 different collections; History of Clouds (Die Geschichte der Wolken, 2003), Lighter than Air (Leichter Als Luft, 1999), Kiosk (Kiosk, 1995) and Music of the Future (Zukunftsmusik, 1991). A second anthology focused on his earlier works, titled The Defense of the Wolves and other poems, is currently on the making, covering the time period 1957-1980. I sincerely don’t know what will become of me once I’ll have completed this 2nd anthology. It’s hard to look for alternatives once you’ve thoroughly translated a poet of such magnitude. Let’s just hope I won’t start popping pills in order to accommodate my frustration.

Your work has been included in Futures: Poetry of the Greek Crisis, which features some of the most daring new voices in Greek poetry “that mourn the fall, damn the greed, and pound a drum for change”. Can poetry act as a political paradigm? Is it in the capacity of poetry to be ‘politically militant’?

I am very suspicious of those who pound a drum. Usually they are the first ones to conform and willingly pound the same drum for others. At the same time, one does not necessarily need to be “politically-militant” to acknowledge that we are in a state of sociopolitical (and hence, ideological) war, one should not even be considered “political” if he/she chooses to occasionally remind us of that fact. Nonetheless, highlighting and diving into the inherent contradictions and adversities of our times is one thing. Writing within the safe and predefined confinements of dominantly constructed fanfares is another. Literature walks hand in hand with history, ideology and desire, all these are known. Reading, writing and publishing poetry may very well mean that you are unconsciously or intentionally joining a foreign legion of some kind; it never presumes, however, that you are a member of an armed militia charged with the divine duty of ideological safekeeping and guidance.

Simultaneously, we are constantly ideological, drenched in the waters of our times, shaped and fashioned by the circumstances of our era. I believe that once we decide to communicate our writings (be it furious confessions, existentialist prayers or mere letters to a honeybee) we should do it foremost as readers-citizens and not as a bunch of uninformed, detached and uninterested, self-proclaimed priests of some obscure religion, that are in a state of privileged communication with God himself.

On a final note, and since you’ve mentioned this anthology, I would like to congratulate the translator and editor Theodoros Chiotis for his excellent work; some of his translations are even better than the original and I can honestly say that this applies for the samples of my work included in this volume.

Writing about the ‘generation of the crisis’ (poets maturing in the 2000s), Vassilis Lambropoulos notes that in the verses of this generation “political hopes have inspired no emancipatory visions”, while it characterizes their poetry as “the poetry of left melancholy”. How would you comment on that?

With all respect to Dr. Lambropoulos, I find the term ‘left melancholy’ rather mild and problematic in describing the harsh reality we are experiencing in the last 10-15 years. And I consider the application of this term into the modern poetic field, even more problematic. One does not have the luxury to comfortably sink into his/her melancholic sentiment while living amidst a collective (and often interpersonal) collapse. To paraphrase William Blake: “the crushed bee has no time for melancholy”. There is a sense of warmth and serenity attached to melancholia, attributes totally incompatible with our current psychological state, where despair and/or determined anger, fear, confusion and/or passive withdrawal, are most probably the prevailing sentiments. Luckily all this range of emotions is adequately represented by the abundant number of contemporary poets along with a subsequent variety of psychological maladies that overwhelmingly transcend the sphere of melancholia. And if I may add, some of them are right-wing, if not in theory, then definitely, in praxis.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE