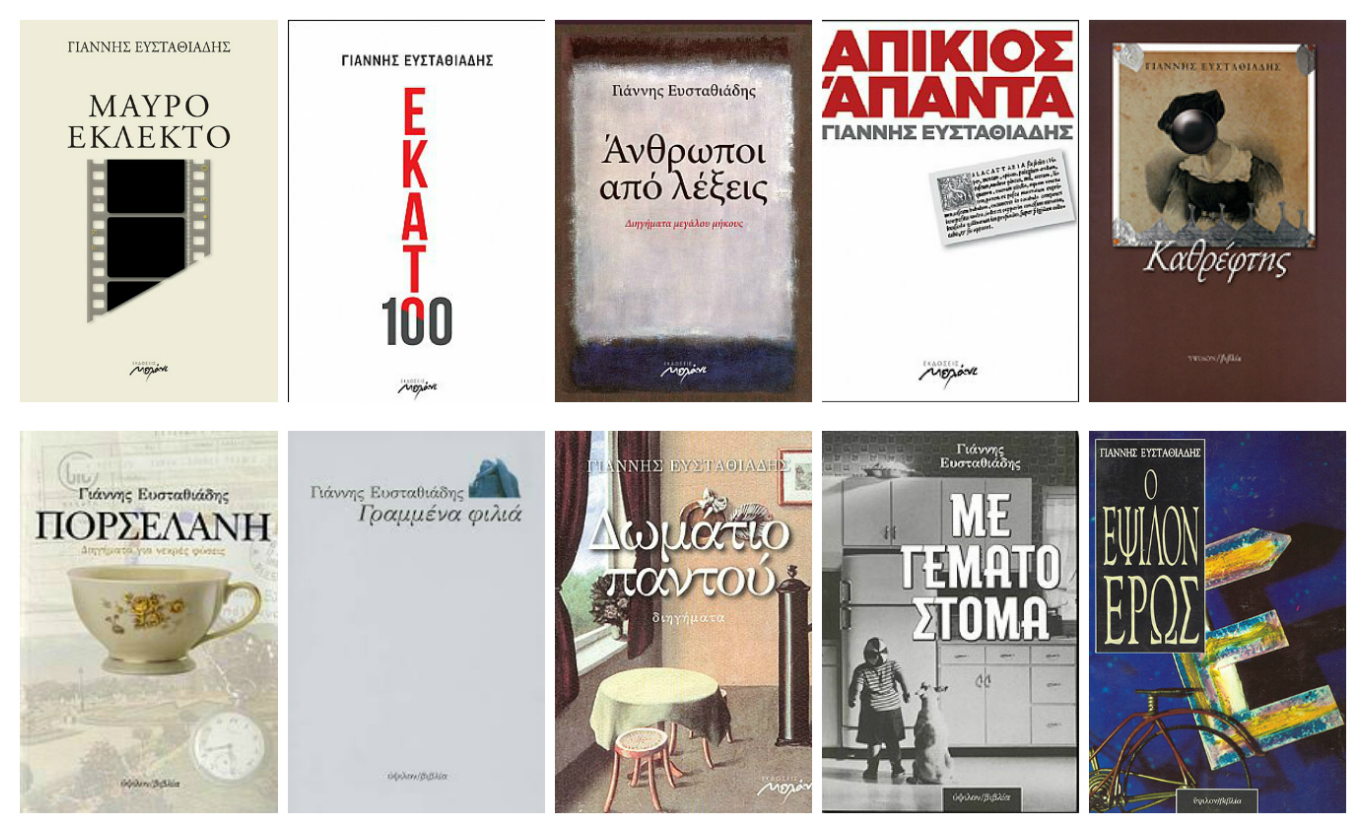

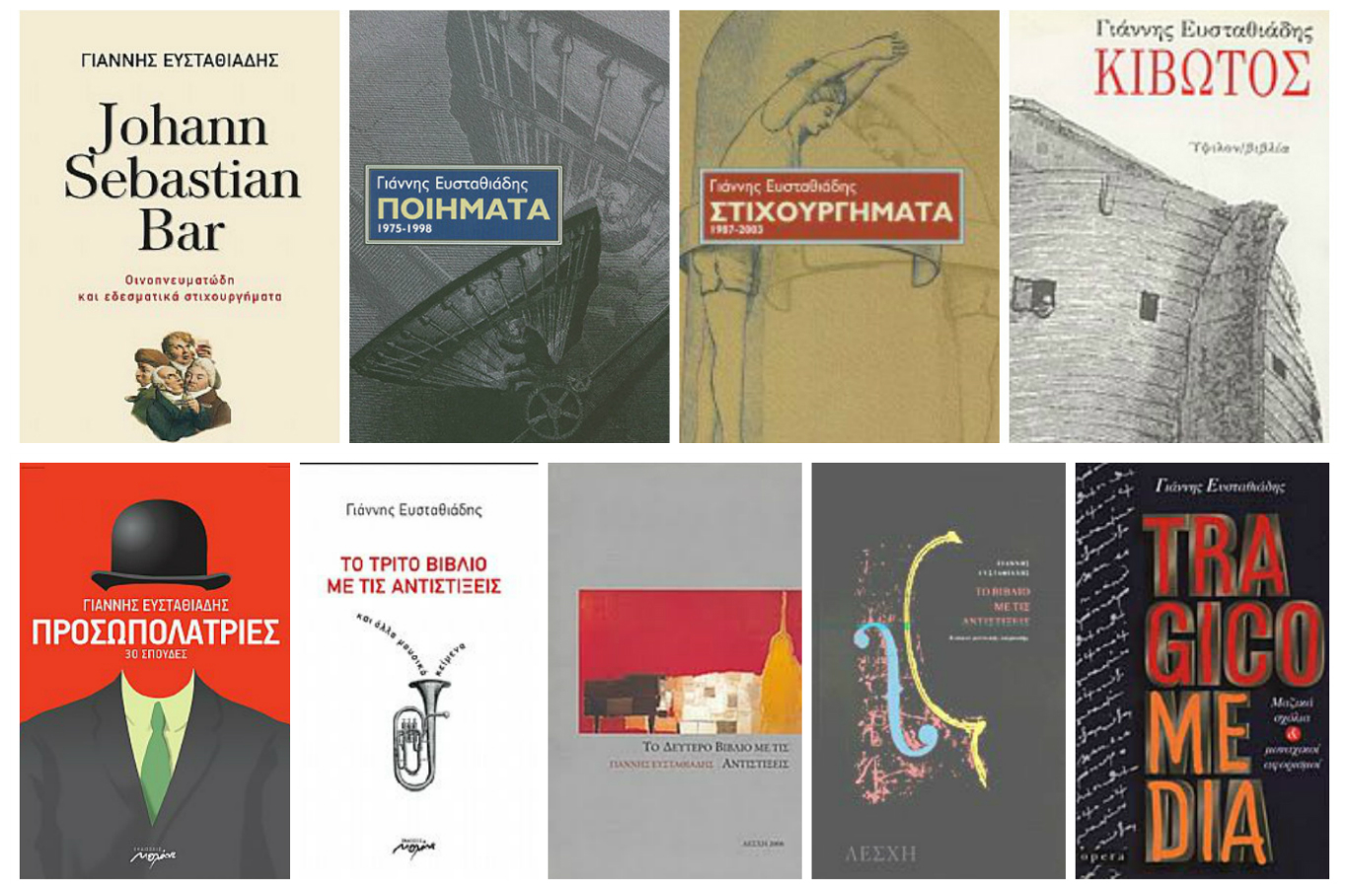

Yannis Efstathiadis was born in Athens in 1946. He studied Political and Economic Sciences at the University of Athens. He has published poetry, novels and short essays on music as well as gastronomy under the pen-name Apikios. He is also music producer for national radio station 3 (Trito Programma) of the Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation. In 2012 he received the State Literary Award for best short story or novel as well as the Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation literary award for his music and literary essays.

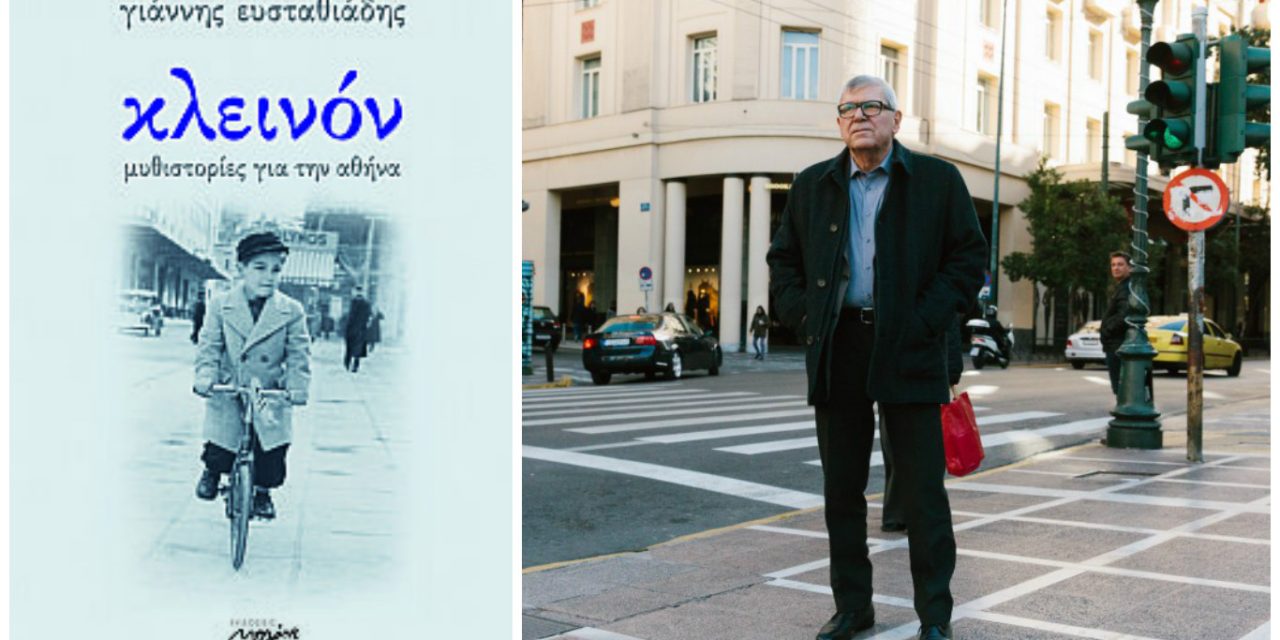

Yannis Efstathiadis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book Κλεινόν, which presents a visual and emotional mapping of Athens through fictional testimonies of renowned (and unknown) people in a multifaceted narration about the city. He comments that Athens “weighs emotionally upon [him]” and that he loves “this bustling presence of people, who, when they commute, entertain, shop or protest, make the city’s temperature rise”.

Asked about his preference for short stories, he quotes Borges, “who asks himself why write a novel when you can unfold the plot in just a few pages”, while he notes that he draws his ideas “from what happens in reality and mostly in the imaginary and the dreamy”. He discusses the similarities between writing and radio production, explaining that “you write on radio as well, just through another technique” and that “a recording studio, unlike a television one, bears the aura of an ascetic cell that also matches the writer”. He concludes that poetry is currently undergoing “a creative poetic renaissance” with a rise of new voices and a revival of older ones.

Your latest book Κλεινόν presents a visual and emotional mapping of Athens through fictional testimonies of prominent Athenians. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book came about by coincidence. It was inspired unintentionally by David Connolly, who, during one of our meetings, asked me if I had a piece of writing regarding Athens to be included in an anthology in English he was preparing about the city. I said no, since all my writings focused mainly on time rather than space. Yet, his question became an indirect bid for me, which resulted in this book. I wanted to draw a polyphonic document about Athens and I chose fictional testimonies of renowned (and unknown) people in relation to the city. I chose people active in different fields (politicians, writers, architects, scientists, athletes etc) so as to achieve a multifaceted narration.

The memories are mostly mine providing the book with an autobiographical character, as the writer puts his own experiences on the words of others. That is the reason the various narrations do not follow a chronological order. They are intentionally disarranged, as is often the case with memories. There is only one concrete symbolism: the first piece (midwife) is birth and the last (Chalepas) is death. And, of course, there are interspersed short pieces by known writers, which act as intermezzos, defining locations and connecting people.

“What is attractive in a city like Athens is the people themselves, not as individual persons but as a strong flavour of life that you get to taste every second of the day”. What does Athens represent for you? How has the human and social geography of the city changed over the years?

For me Athens – actually, its very centre – is the city where I was born and the city where I grew up. Thus, it is a city that weighs emotionally upon me and the same goes for its bad aspects (impersonal buildings, unregulated and artless signs, stray wires etc). I love Athens and I love it with the difficulty it entails – it’s easy to love beautiful cities, as my wife likes to say. I love this bustling presence of people, who, when they commute, entertain, shop or protest, make the city’s temperature rise. I love Athens during all its eras, in its entirety. Even more so – as it becomes evident in the book – I remember Athens, I don’t just feel nostalgic. Nostalgia often turns overemotional, which in no way characterizes me either as a person or as a writer. I opt for the Doric simplicity of memory.

You write short stories that are often snapshots of a person’s life. What makes you choose this form of writing? Would you argue that the short form can better depict ‘the human condition’?

Indeed, I write short stories – short novels as I tend to call them – and this may be due to my poetic origins; I solely wrote poems during the first 20 years of my writing career. But what guides me is a quote by Borges, who asks himself why write a novel when you can unfold the plot in just a few pages.

“Whatever the country, whatever the landscape, a writer’s influential space would always be the square metres of his desk”. Do you follow a particular writing procedure? Where do you draw your inspiration from?

From the few square metres of my office I try to communicate both with the “outside” and the “inner world”; to describe, to record, to witness, to trace, to “hear”, and to communicate. I draw my ideas from what happens in reality and mostly in the imaginary and the dreamy. At times I am a realist, and often a surrealist. I don’t believe in inspiration. I believe in observation, memory and invention.

A novelist, a poet, an essayist, a radio producer. What is the binding thread?

It’s writing that unites them all. I will repeat something that I said some years ago: “The radio; you write on radio as well, just through another technique. In essence, you write – otherwise you cannot control either time or style– imitating the spontaneity of improvisation and seeking immediacy and warmth. Besides, I see many similarities between a recording studio and a writer’s office: a recording studio, unlike a television one, bears the aura of an ascetic cell that also matches the writer. You are alone (the sound engineer is always a discreet presence), the light is dim, you wear headphones which isolate you from the outside world and you just listen to your own voice. Isn’t it what a writer does in the few square meters of his office? He is alone, in a low-lit office and he only “hears” his own voice…”

You have stated that you are an avid poetry reader. How do things stand as far as literary, and more specific poetic, production in Greece is concerned?

I believe poetry in Greece underwent a crisis towards the end of the millennium – a more or less barren twenty-year period. Thus, it was with great joy that I witnessed a rise of new voices or a revival of older ones in recent years! We stand before a new creative poetic renaissance.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou