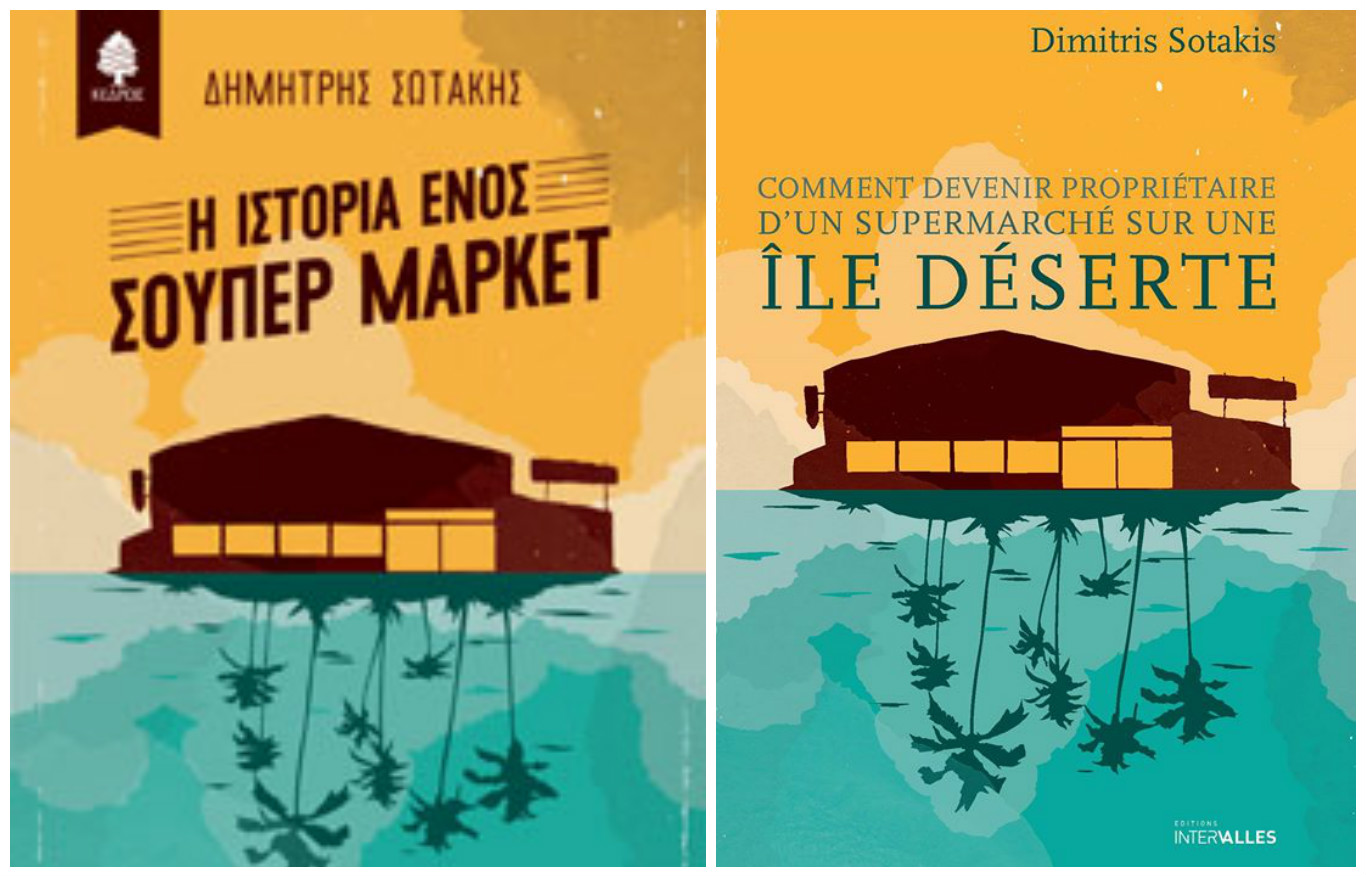

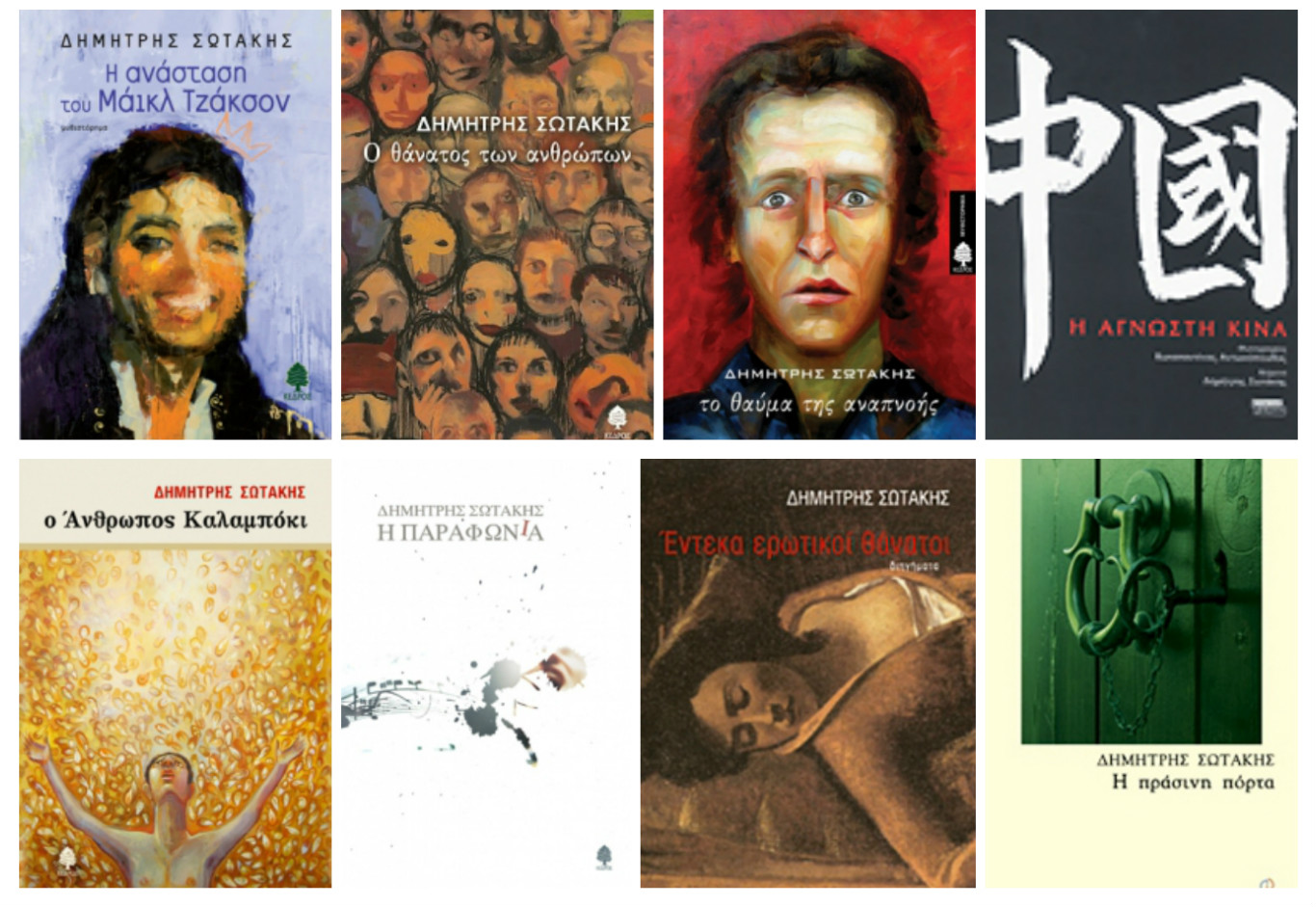

Dimitris Sotakis was born in Athens in 1973. He has published eight novels: H ιστορία ενός σούπερ μάρκετ [Τhe Story of a Super Market] (Kedros Eds., 2015), Η ανάσταση του Μάικλ Τζάκσον [The Resurrection of Michael Jackson] (Kedros Eds., 2014), Ο θάνατος των ανθρώπων [The Death of Humans] (Kedros Eds., 2012), Το θαύμα της αναπνοής [The Miracle of Breathing] (Kedros Eds., 2009), O άνθρωπος καλαμπόκι [The Corn Man] (Kedros Eds., 2007), Η παραφωνία [Dissonance] (Kedros Eds., 2005), Η πράσινη πόρτα [The Greek Door] (Metaixmio Eds., 2002), Το σπίτι [The House] (Kastaniotis Eds., 1997) and one collection of short stories: Έντεκα ερωτικοί θάνατοι [Eleven Love Deaths] (Metaixmio Eds., 2004).

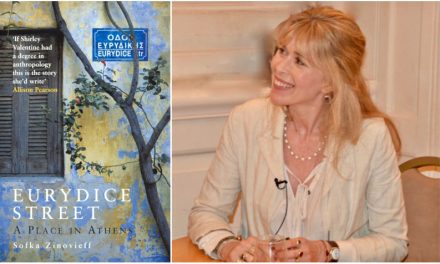

His novel The Miracle of Breathing won the award for Best Novel at the Athens Prize for Literature and was shortlisted both for the European Excellence Award for Literature and the Jean Monnet Prize in France. It was published in France, Serbia, Italy, Taiwan, FYROM and Turkey. His most recent novel The Story of a Super Market was recently translated into French by Editions Intervalles under the title Comment devenir propriétaire d’un supermarché sur une île déserte.

Dimitris Sotakis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest novel which tells the story of a journalist from New Zealand, who, when he finds himself shipwrecked on an unknown desert island, decides to build a super market in a personal adventure with surreal consequences. He explains that the “themes of the grotesque, hyperbole and bluster” which permeate his writing “have the ultimate aim of demonstrating the existential anguish about life of modern man and our perpetual desire to conquer a life that we never had”, noting that his books “are about cries that have turned into stories”.

Asked about what makes Greek literature appealing to foreign readers, he comments that “foreign publishers have, until recently, been interested in some more folkloristic parameters of Greek literature and of course in the Greek crisis”. He explains that he doesn’t believe in “generations of writers” since “literature is a very personal matter” and concludes that he is very optimistic that “the immediate future has some great Greek novels in store for us”.

Your latest novel The Story of a Super Market has just been translated into French. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book tells the story of Robert Man, a journalist from New Zealand who, during a business trip, finds himself shipwrecked on an unknown desert island, in the middle of nowhere. There, all alone, instead of sinking into despair, he -all of a sudden- finds his real self and decides to build a Super Market. Equipped with the imagination and the desire to climb the social ladder, a personal adventure begins with unexpected, surreal consequences. The publication of the book in France is a wonderful thing for me; this is actually my second book being published there, following that of The Miracle of Breathing three years ago.

The paradox and the absurd seem to permeate most of your books. What purpose do they serve?

The paradox for me is a stylistic vehicle, with which I can ‘travel’ more safely towards the worlds I create by writing. Reality, as a given condition, never fascinated me; after all, I write to escape from reality, this is my main predisposition. The themes of the grotesque, hyperbole and bluster in my stories, however, have the ultimate aim of demonstrating the existential anguish about life of modern man and our perpetual desire to conquer a life that we never had. The core of my books is all of us, you and me, and how we’re actually striving to lead this personal vehicle, our own lives.

How has the way you perceive literature evolved in the course of twenty years of writing? And what has been the effect on your personal way of writing?

When I started writing, I just wanted to narrate stories, to exist as someone who would give shape to a bunch of people, who would “give birth” to them as in flesh and blood. Yet, as time went by, that just wasn’t enough. Gradually, by discovering my personal style, I longed to add my personal touch, to talk about life as I myself understand it, as well as about my anguish for everything that happens to us till the moment of our death. In essence, my books are about cries that have turned into stories. Instead of saying something directly, I do so by writing a novel, in my loneliness. My life has changed due to my books; I consider it only natural after all these years. What I need for sure now is a good psychiatrist.

You have recently said that nowadays “writers seem to lead a life, basically electronic, denying their fundamental role, the quest, the deviation, the existential anxiety, the wonder”. Could you elaborate on that?

It’s something I find quite troubling. I reckon that we have largely come to lead a secluded life; an almost autistic, self-indulgent, life. Modern man and of course fellow writers now live so alone, circled by a technological armory but away from literary groups, great friendships, confrontations and the spark that only personal contact can ignite. We have, in a way, become invisible; what we usually tend to see is our reflection or a reproduction of our reflection in the electronic media. I would be delighted if this new reality gradually moved to something more mentally healthy.

The Miracle of Breathing has been translated in various languages and was shortlisted both for the European Excellence Award for Literature and the Jean Monnet Prize. How does it feel for a Greek writer to be translated abroad? What is it that makes Greek literature appealing to foreign readers?

Thepublication of my books outside Greece generates in me an almost metaphysical feeling. The fact that I write a book confined in my room, which is later read by some people in China, is actually an indescribable feeling. The Miracle of Breathing is and continues to be doing well in many countries and the same goes now with The Story of a Super Market. Undoubtedly it’s a very important moment for me and I truly thank all my readers, in whichever part of the world they may be.

Yet, foreign publishers have, until recently, been interested in some more folkloristic parameters of Greek literature and of course in the Greek crisis. I don’t belong to either of the two categories. Inevitably I write as a Greek, but I do not solely address “Greek issues”; I am more interested in the people living on this planet.

Having been part of the Athens Prize for Literature committee, what do you consider to be the potential and prospects of the new generation of Greek writers?

I don’t believe in generations of writers. I reckon that literature is a very personal matter. Yet, there is no denying that people living in specific lengths and widths of space-time, share similar images of the world. I look forward to good Greek books, books that will instill in me the so wonderful feeling of reading bliss. In the last few years, we had difficulty – in the Athens Prize for Literature committee – tracking down truly good books and we were fortunate enough to trace some very notable ones. I am very optimistic that the immediate future has some great Greek novels in store for us.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE