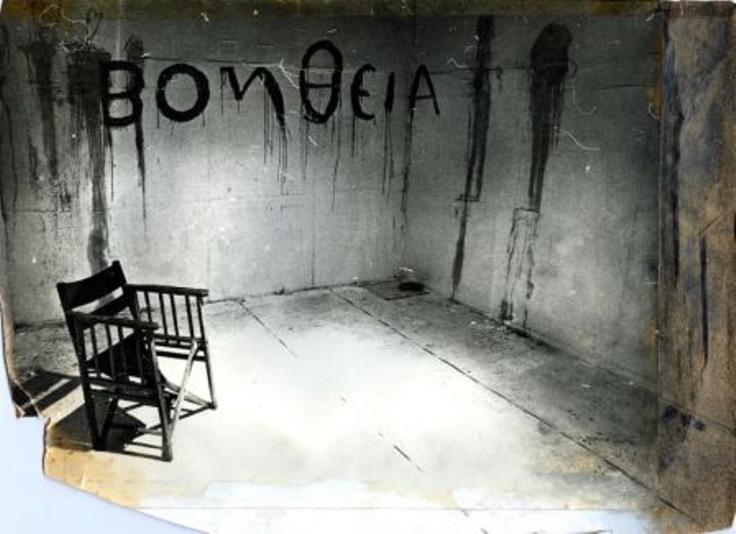

Maria Karavela, Hilton Gallery, Athens (1971), scraweled an eloquent plea of “Help”

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the seizure of power in Greece by a group of right–wing army officers (21 April 1967) imposing for seven years a regime of military dictatorship, also known as the Regime of the Colonels or the Junta (1967-1974).

In the first of a series of accounts of the period, Greek News Agenda asked Eleni Ganiti, Art historian at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) to offer us a glimpse of the reaction of the Greek visual arts scene during the dictatorship*:

The 21st of April, 1967 has been a portentous date in the history of modern Greece. The dictatorship came after a period of political instability in the country, intercepting the normal course of things at the political, social and economic sector. Such a disorder could not leave the cultural life of the country unaffected. How did the art world react and what were the effects of the dictatorship on the Greek visual arts scene? It is interesting to attempt an approach to these questions through a look at the exhibitions and the artworks that were created and exhibited in the country during the seven years of the Military Regime.

1967: The first reaction

The imposing of the dictatorship on the 21st of April, 1967 numbed the entire Greek society. The artistic community’s first reaction was silence, as artists consciously decided to abstain from any public activity, believing they could fight the Regime by boycotting it.

The “silent” period lasted two years, until 1969. From the beginning, there were voices that disagreed with this absence from the cultural life, arguing that artists and intellectuals, being the most “sensitive” elements of society, should speak up and show their protest. Furthermore, the younger artists who were at the beginning of their careers, felt restrained; they were unable to express themselves publicly or become part of the country’s art scene, they could not evolve artistically and form their own artistic idiom. We must not underestimate the fact that participating in a local art scene was a matter of “survival” as artists needed to work in order to survive, not only financially but also artistically. It soon became obvious that isolation was not the solution. It could only lead to the devitilization of Greek art.

A collective reappearance of the artists, with exhibitions that would take a character of protest and resistance against the Military Regime, was being vividly discussed in artistic cycles. Robert Kennedy’s assassination was considered to be the right timing for such an action, however this finally never happened (1).

Break the silence: The exhibition of Vlassis Caniaris

The exhibition that signaled the exit from the artists’ silence came in May of 1969 by Vlassis Caniaris. This historical and much-discussed exhibition took place at the “New Gallery” in Athens and had an intense political, and in a way activist character, as it aimed not only to protest against the Regime but mainly to mobilize the Greek people.

Vlassis Caniaris works’ (1969 and 1974)

The works displayed included human members and objects in plaster, barbed wire and red carnations, all of them -especially plaster and carnations- carrying a deep and obvious symbolic meaning. The plaster, which morphologically belonged to Caniaris’ work (he was using plaster since 1963-64), made a direct reference to the dictator’s Papadopoulos famous phrase “Greece is sick. We had put her in plaster. She shall remain in plaster until she recovers”. [Η Ελλάς ασθενεί. Την έχομε θέσει εις τον γύψον. Θα παραμείνη εις τον γύψον μέχρις ότου ιαθεί].

There was no exhibition catalogue, as Caniaris himself had censored the texts that were going to be published, in order to avoid that the exhibition was “targeted” by the Junta and so that others, especially those working in the resistance, would not lose their courage. Instead of a catalogue, each visitor was offered a red carnation growing out of a small plaster cube, symbolising the idea that the carnation is growing despite the plaster. The exhibition was a great success -Caniaris had to make another 1000 plaster cubes with carnations for the people visiting the exhibition during the 21 days that it lasted- fulfilling its aim. The story was covered by the international press. After the exhibition, the artist left for Paris.

Exhibitions with meaning

After Caniaris’ exhibition, art activity gradually begun again, especially from 1970 onwards. The majority of the artists refused to participate in state events (Biennales, Panhelenic exhibitions, etc) so most of the exhibitions were taking place in galleries, private venues or foreign institutes. Some of these exhibitions took the form of anti-dictatorial expressions, indented or not, since the works presented (indicative of artistic tendencies of the time), had multiple meanings and could be translated and received by the audience differently, according to the sociopolitical context. In any case, these events contributed to the creation of a climate of solidarity and united artists and audience against the dictatorial regime.

Maria Karavela – A voice of protest

In November 1970, Maria Karavela held an exhibition at the “Astor Gallery” in Athens, which is considered to be the first “installation-environment” exhibition presented in Greece (the artist herself called it “exhibition in space/space exhibition”). The gallery walls were painted grey, while red and white tied sacks, reminding of humans, were positioned in various places throughout the gallery. A cage containing a white real – size human figure was placed in the middle of the gallery space. The symbolism of Karavela’s “environment’ against the suppression of the Regime and the references to freedom, death and isolation were obvious.

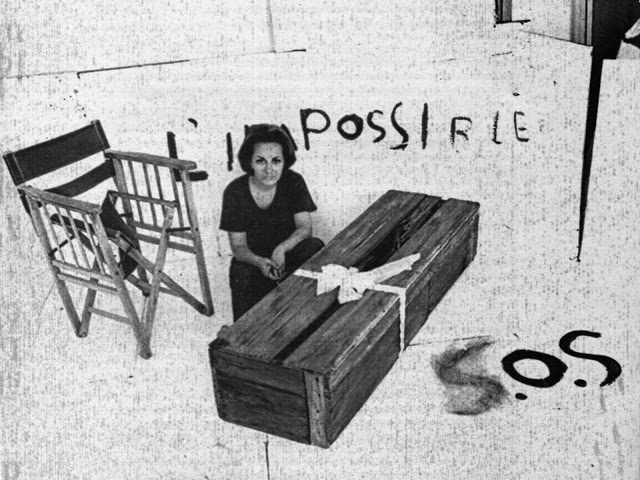

In May 1971, Karavela created a second “environment” at the “Athens-Hilton Gallery”, with stronger content. A square cell was installed inside the gallery space, while words such as “freedom” and “help”, were written in red paint on the external walls. Human figures in real size were lying on the gallery floor. The artist managed to create a claustrophobic, tragic environment with simple, easily understood elements so that the viewers, whose participation was necessary for the whole work to “function”, could perceive her message according to their experience, their sensitivity and their personality (2). This exhibition was censored and shut down a few days after the opening. The artist left for Paris losing her teaching position at the National Technical University of Athens.

Maria Karavela is one of the few cases of artists who expressed early and clearly her anger and opposition towards the Junta and these two exhibitions had a clear anti-dictatorial meaning.

Maria Karavela is one of the few cases of artists who expressed early and clearly her anger and opposition towards the Junta and these two exhibitions had a clear anti-dictatorial meaning.

Elias Dekoulakos – The exhibition that never happened

Elias Dekoulakos produced a series of paintings in 1968-73, adopting a kind of photographic realism with a critical content against the violence of the dictatorship, expressing also his contempt towards the Regime. Some of these paintings were going to be displayed at the “Athens-Hilton Gallery” in 1973, but a few hours before the exhibition opening, the police -after the accusation made by a passing-by school teacher- demanded that some of the exhibits be withdrawn because of their provocative, for public decency, content. It is funny, although not uncommon, how the authorities censored the exhibition for the wrong reasons, failing to see the true meaning of the works. The artist refused to withdraw the paintings and the exhibition was cancelled. The gallery, which was housed inside the Hilton Hotel, decided, together with the Hilton director, to interrupt exhibition activity for a while, though this meant its final closure (3). The Dekoulakos’ exhibition however was held later, slightly modified, at the “Nees Morfes Gallery” in Athens.

Criticizing the Junta

The “Sculpture for public participation – participation prohibited” environment of Theodoros, sculptor in 1970 at the Goethe Institute, Athens, the encased people of Dimitris Alithinos in 1972 at the Studio 47, Athens (organized by the Desmos Gallery) and in 1973 at the “Ora Cultural Center“, as well as the exhibition of the art group New Greek Realists (1971-73) consisting of 5 young artists, Jannis Psychopedis, Kleopatra Digka, Chronis Botsoglou, Kyriakos Katzourakis and Yannis Valavanidis in 1972 at the Goethe Institute, Athens, are all examples of exhibitions that contained critical references to the Junta, although their aim was not to constitute a clear anti–dictatorial action.

New Greek Realists, the Invitation to the Goethe Institute, Athens exhibition (1972)

Symbols and meanings: Anti – dictatorial artworks

As we have already seen, Greek artists were affected by the dictatorship. Works with critical content were created and exhibited during the seven years; however, these were not the majority of the art production. As Alexandros Xydis mentions, in the beginning of the 70s the number of Greek artists dealing with the painful Greek affair have been reduced. Instead, many of them were occupied with the considerations of the international art of the time, such as the society of consumption, the technology, the isolation of the individual, the suffocation of life in the big cities, and in search of new art mediums that could express their concerns. They were expressing their reaction in a more subtle way, mainly through symbolisms and references to more general situations.

With the exception of a number of artists who politically belonged to the Left and had an anti-dictatorial action, producing works of political and anti-dictatorial content, artists who also created such works were mainly socially – minded, in a wider sense, (such as Vlassis Caniaris or Maria Karavela that have been mentioned above). It is indicative that most of these artists continued to express their social and political concerns in various ways throughout their careers. Of course, there is the case of artists who created just a couple of such works, returning afterwards to their own artistic expressions. Artworks with critical references to the dictatorship were produced and exhibited even in the first years of the political change – over.

Painting the “black years”

Dimosthenis Kokkinidis is probably one of the most representative cases of artists that produced “anti-dictatorial” works during the dictatorship. He could be characterized as a social-minded artist, creating work -mainly until the 80s- of critical content with eloquent references to the social and political history.

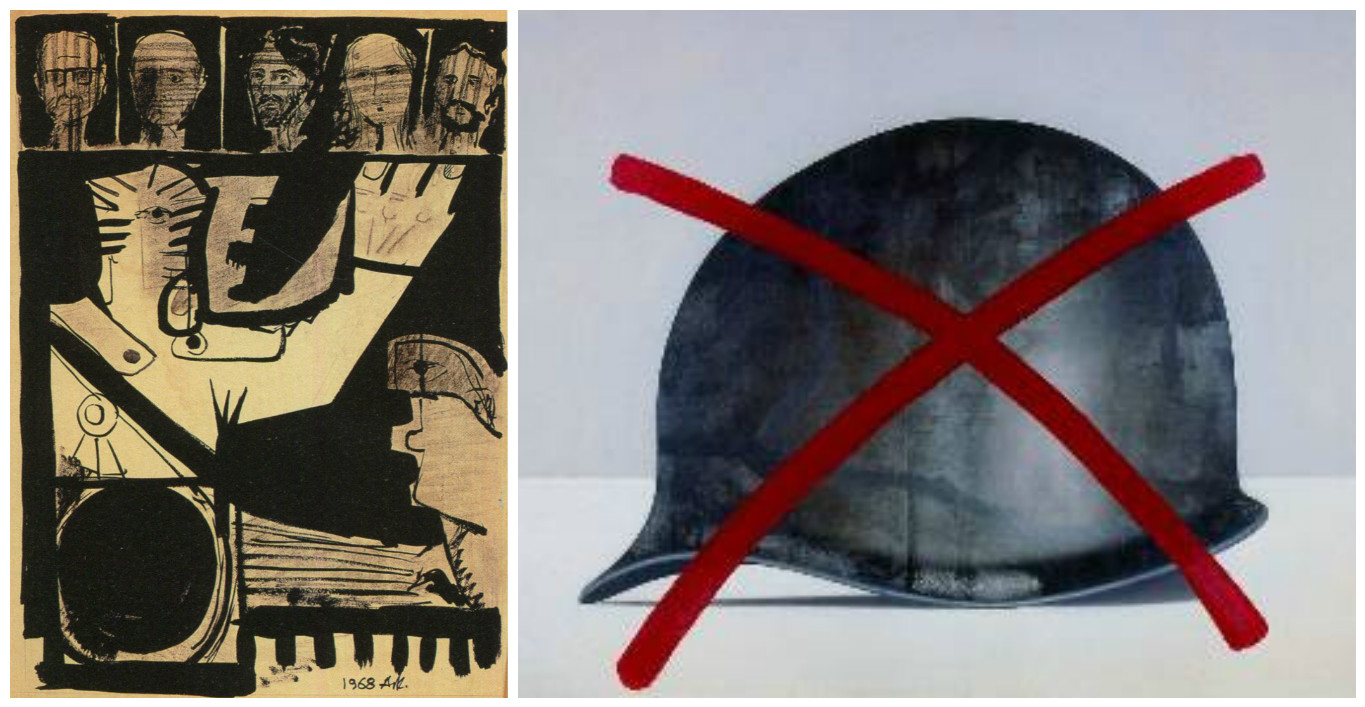

In May of 1967, stimulated by the recent events, he started painting a series of works under the title “And regarding the remembrance of evils…” (1967-68), depicting distorted images of the dictators and their people (priests, judges etc.), drawn sometimes almost like caricatures, in an expressionistic style, and other times abstractly. These paintings were full of strong symbolisms: the American flag suggesting the American interference, the Greek flag with different forms and symbolisms, the judges, “faceless individuals, victims and victimizers simultaneously” (5) painted sometimes faceless and other times like human puppets or mechanical constructions, stressing their obedient attitude throughout the seven years of the Junta. As the artist himself says, he stopped painting these works in December of 1967, with the exception of some less provocative paintings which he created in spring of 1968, when he realised the danger and he understood that they could not be exhibited.

Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, July 1967

“And regarding the remembrance of evils…” was the starting point for his second entity of paintings on the dictatorship, entitled “Identities” (1968 – 74), which were exhibited in 1971 at the Zouboulakis Galleries, Athens. Identities depicted the victims of the Regime, friends of the artist, well known personalities or complete strangers, often taken from newspaper photographs, who have been arrested, brought to trials, imprisoned or tortured. At the same time, Kokkinidis created the entity “Motherhood” (1968 – 74), inspired by the birth of his daughter. In Motherhood, he deals with the relationship of mother and child, the fear for the future, especially the future of young people, and the absence of the mail figure, the father, who often, during these years, was in prison or in exile. All these paintings were full of meanings and symbols.

Apart from Kokkinidis, artists such as Giannis Gaitis, George Touyas, Alexis Akrithakis, Dimitris Mytaras, Sotiris Sorogkas, Lefteris Kanakakis, produced interesting works of “anti-dictatorial” content.

Art in the years of the dictatorship: Some conclusions

The dictatorship came at a time when the visual arts scene in Greece was flourishing, causing regression mainly because it interrupted contacts with international art, putting the country into isolation, especially during the first years. The return of Greek artists, who had studied and lived abroad and were bearers of new and refreshing ideas, stopped, a number of artists had to leave the country for political reasons, while the rest decided to abstain from art activity as a reaction to the dictatorship. During this “silent” period the art dialogue between artists themselves as well as between them and the audience was paused. Furthermore, the censorship that was imposed and also the doubtable aesthetical standards of the dictators and their people, responsible for art and cultural policy, did not contribute to the progress of the Greek art.

After the first two years, artists decided to break the silence and started exhibiting again. Obviously, many of them were influenced to some extent by the overthrow of democracy and the tragic events that followed, a fact that was depicted in their works. Artworks and exhibitions with political and anti – dictatorial meaning appeared. Sometimes the meaning was clear, more often the message was implied through symbolisms because of the censorship. The audience learned not only to decode messages but also to receive and translate the multiple meanings of an artwork according to the prevailing sociopolitical context. “(…) this interesting form of anti – dictatorial solidarity, favored, among others, the reception of art tendencies, which some years ago would have been considered radical. Both artists and viewers were readier than ever to exceed the traditional conservatism of the average Greek of the time. Radical forms, like radical ideologies, had a bigger impact, maybe because the dictatorship did whatever possible to fight everything that was radical (…)”(6). Indeed, it is noteworthy that during the period of the dictatorship, elements such as the use of unconventional material, the intervention of space and time into the art work, the concept of the ephemeron (environments, installations, happenings, performances) were introduced into Greek art. The social and political conditions also favored the new, various forms of photorealistic art with critical content in the spirit of Pop Art and – what is considered to be its French version – Nouveaux Realism. Constructivist – geometrical tendencies can also be traced in the works of a number of artists (e.g. Pantelis Xagoraris, Opi Zouni etc.) who were working in their ateliers and starting from their own experimentations converged to a common field of research.

All these tendencies and experimentations will lead Greek art to the pluralistic decade of the seventies and the post dictatorial era.

Eleni Ganiti, National Museum of Contemporary Art

(1) Πέγκυ Κουνενάκη, Νέοι Έλληνες Ρεαλιστές, Εξάντας, Αθήνα, 1988, p. 24

(2) Αρετή Αδαμοπούλου, Ελληνική μεταπολεμική τέχνη. Εικαστικές παρεμβάσεις στο χώρο, University Studio Press, Θεσσαλονίκη, 2000, p. 68.

(3) Αίθουσες τέχνης στην Ελλάδα: Αθήνα – Θεσσαλονίκη 1920 – 1988, Άποψη, 1988, p. 73.

(4) Αλέξανδρος Ξύδης, «Το σημερινό πρόσωπο της Ελληνικής τέχνης. Πορεία ως το 1974», Προτάσεις για την Ιστορία της Νεοελληνικής Τέχνης, Α. Διαμόρφωση – Εξέλιξη, Ολκός, Αθήνα, 1976, p. 262.

(5) Andreas Ioannidis, “The painting of D. Κokkinidis”, Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, metropolitan Hospital, Adam Editions, Pergamos S.A., Athens, 2002, p. 24

(6) Μάρθα Χριστοφόγλου, «Η Καταλυτική επίδραση της δικτατορίας», αφιέρωμα Τέχνη και Πολιτική, Επτά Ημέρες – Καθημερινή, 9 Ιανουαρίου 2005

*This text was first published in a more extended form, under the title “The Military Dictatorship of April 1967 in Greece and its repercussion on the Greek visual arts scene,” at the UK-based Greek Politics Specialist Group‘s website and originally presented at the 4th PhD Symposium of the Hellenic Observatory, LSE, June 2009.

Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, Repression (1968), Elias Dekoulakos, Study (1972)