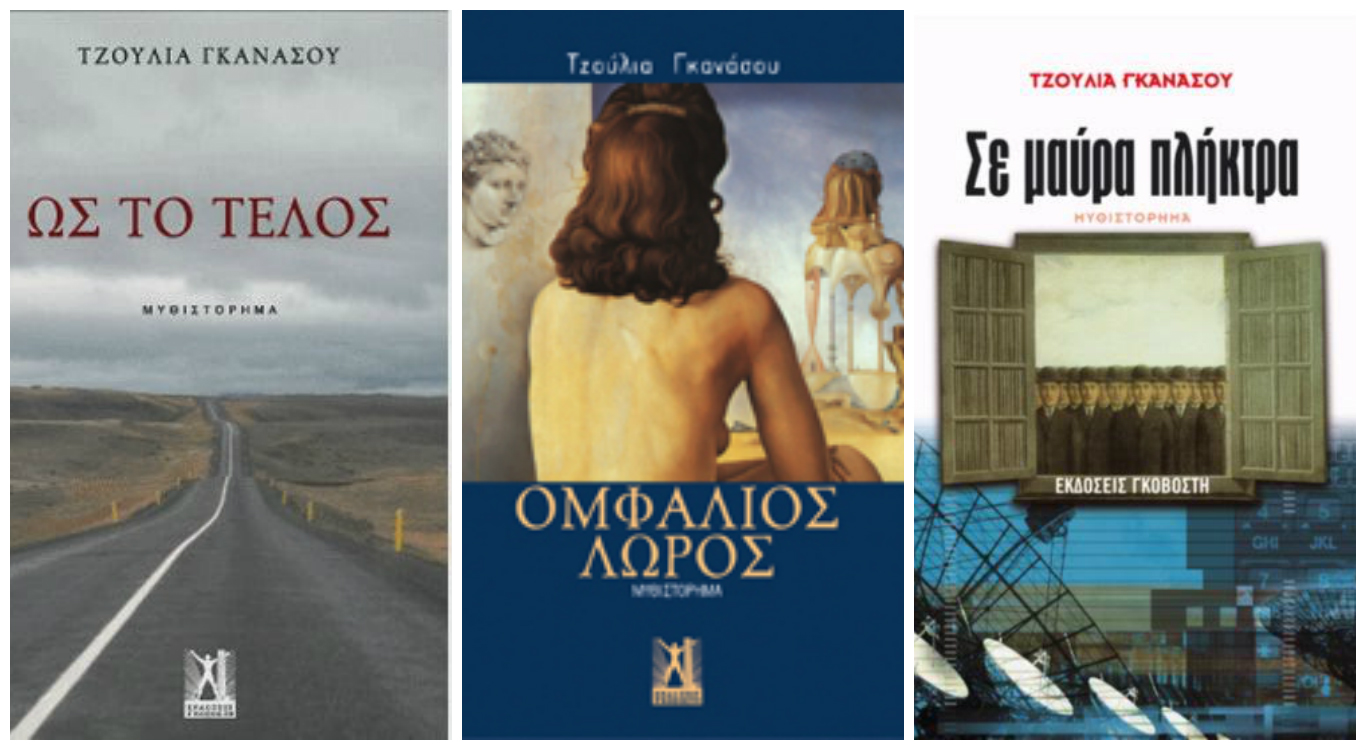

Julia Gkanasou was born in Athens. She studied Computer Science in Athens and Information Security in London, Literature in Paris and Edinburgh and European Civilization in Hellenic Open University. She has published the following books: On Black Keys (novel, Govostis, 2006) – parts of the book were included in the collective edition “Universal Cities” (University of Edinburgh); Umbilical cord (novel, Govostis, 2011) – participation in: 4th Dasein International Literary Festival, 1st Young Writers’ Festival in Athens and 9th Young Artists’ Festival in Glasgow; Till the end (novella, Govostis, 2013) – shortlisted for the Young Writers’ Award 2013 of the literary magazine “Klepsydra” and the National Literary Award 2014; Down on my knees (novella, Govostis, 2017) – honorary distinction at the Mediterranean Short Stories Contest 2017, University of Exeter.

Julia Gkanasou spoke to Reading Greece* about her most recent book Down on my knees, noting that “the realization and management of our mortality, of our limits, and the impact on human existence” are some of her writing obsessions, while a recurrent theme in all her books is “the anguish for the passing of time, for decay, for the body as a vehicle for uttermost pleasure and supreme pain”.

She comments on “the extrovert character of the new generation of Greek writers, novelists and poets”, whose writing “incorporates influences of not just world literature but global artistic trends as a whole”, and concludes that in her case the bet was to depict something Greek and unique in a global way.

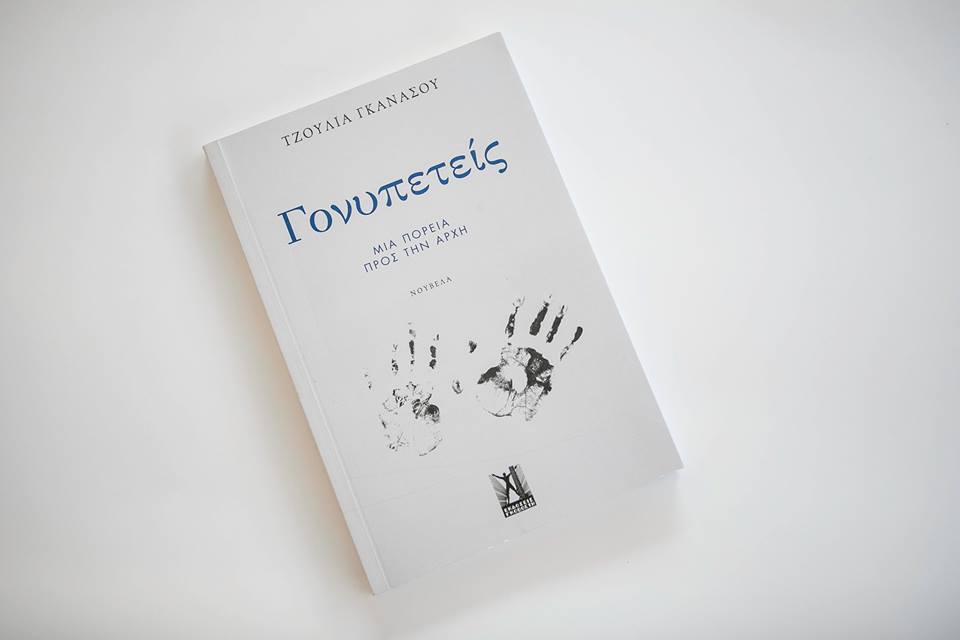

Your most recent novel, Down on my knees, was recently published. Tell us a few things about the book.

In Down on my knees, a woman on her knees starts her ascent in order to fulfill a promise, a vow. She envisions the miracle. She has no options left. And the same goes for all those on their knees alongside her. However, she is not out there for the usual reasons; not even for the reasons she cites in the beginning. What she remembers, what she experiences along the way and what she admits change things completely. ‘On their knees’ are all those with no options left to them. ‘On their knees’ are the mortals who are fervently faithful. ‘On their knees’ are those who believe that the unfeasible could be made feasible. ‘On their knees’ are those who continue to fight despite and beyond all odds, against the forces of degradation, loneliness and deprivation. ‘On our knees’ are all of us when we tread back anew to our beginning.

In her review of the book, Irene Stamatopoulou comments that “the primary question permeating your writing is what binds us to the world and how the awareness or even ‘negotiation’ of our limits, at every level, can transform our earthly experience”. What would you say are your ‘writing obsessions’?

The realization and management of our mortality, of our limits, and the impact on human existence, are some of my primary writing obsessions. This is the reason why a recurrent theme in all my books, expressed intensely and variably, is the anguish for the passing of time, for decay, for the body as a vehicle for uttermostpleasure and supreme pain.

At the same time, I am particularly interested in change, in how living organisms are transforming over time, as well as during historical and narrative conjunctures. My attention is usually turned not to the distant past, but to the potentially gloomy yet mostly promising future. This fact is connected in my books with the presence of science as a means of restructuring human reality, and quite often, as a means of controlling humanity’s course. The role of memory is added to this, which, along with the effects of the most ardent desire, acts as a point of self-reference or as a path to alteration, mobilization, catharsis and faith.

From On Black Keys in 2006 to Down on my knees in 2017 what has changed and what has remained the same in your writing?

I think that my writing has become more abstract, Spartan, unadorned and void of unnecessary embellishment, while it has gradually turned to shorter forms, towards a condensed multi-dimensional universe which starts from a specific juncture and then spreads to cover everything.

Even so, I believe that my literary style remains personal and particular, full of intense cinematic images and a narration open to multiple versions of being. Although narrative modes are incessantly enriched, I consider myself part of the immense tradition of European modernism, in terms of themes as well as on structural and functional levels, with however a touch of Greekness, which converses equally with the global and the universal. I still relish the poetic approach of intimate moments as well as the delirious which has the power to connect the realistic with the surrealistic, the grotesque with the cruelly objective and the idealistically imaginary.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of both poetry and prose in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines and readings in public squares, to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained?

I believe that this phenomenon is explained by the fact that literature is like milk: it makes strong bones.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek writers is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. What is it that makes a national literature appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek writers incorporate foreign influences in their work?

I believe that current, and chiefly the younger generation of Greek writers, given that they have travelled more as well as lived abroad, have learned to view, read and write in a more “open” way that incorporates influences of not just world literature but global artistic trends as a whole. Taking also into account the fact that many of them read “major” literary works in the original, it’s easy to see the extrovert character of the new generation of Greek writers, novelists and poets.

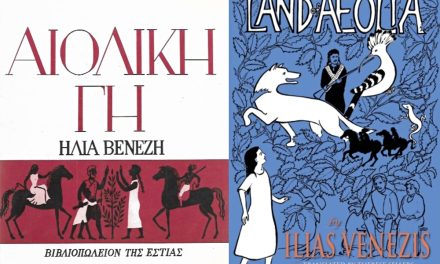

Within this framework, Greek literature is changing. When I wrote On Black Keys, I lived in London. Literary circles there showed interest in the book, as it took place in a city, a so-called global city, and referred to the insecurity of our deepest secrets, the defeat of what is private, personal, and undisclosed. Thus the book was distinguished and excerpts were included in an edition on modern global cities published by the University of Edinburgh. It was then that I first realized that foreign readers were completely indifferent to the ‘greekness’ of the book, although the main female character bore distinct Greek traits. With the exception of our great Nobel laureates, classical writers and ancient Greek texts – and maybe some works on the subject of the crisis – neither folklore nor the contemporary version of Greece, as depicted in literature, actually interest foreign readers.

While participating in a European literature festival with my second book Umbilical cord, I realized that the challenge was huge. In Sorbonne, for instance, the book was distinguished for its originality: it referred to the sheer contrast between the reality of multinational companies trading the body and a circus of people with physical particularities glorifying the body in all its forms. At the festival, what attracted interest was not the “greekness” of the book but its atopic and timeless – with futuristic elements – global character. My concern about what could differentiate me as a Greek literary voice, so that my birthplace would be a point of reference, distinction and involvement, had reached its zenith.

Nonetheless, when I wrote Down on my knees, which refers to an exceptional happening that takes place exclusively on the Greek island of Tinos, I decided to submit the first part to a literary competition organized by the Department of Mediterranean Studies of the University of Exeter just to see what the reactions would be. The book is among the four shortlisted to receive an honorary scholarship funding their translation into English. The note accompanying the distinction wrote: “We would like to thank you for depicting something so Greek, Mediterranean and unique in such a ‘global’ way”.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE