A vibrant capital in the midst of economic and migratory crisis, a metropolis of contrasts, a cultural hub in constant flux, Athens’ many facets are what make it one of the most interesting cities in Europe. A few days after the end of the Greek leg of Documenta 14 – “Learning from Athens” (8.4-16.7.2017) Greek News Agenda and Grèce Hebdo* interviewed sociologist Nikos Souliotis, Research Fellow at the National Center for Social Research (EKKE).

Nikos Souliotis spoke about Athens’ modern cultural identity, its new public and private cultural infrastructures, how social life in city has changed after the 60’s, the transformation of the city center through its rehabilitation and the development of cultural and leisure activies in the 90’s, the “labour division” between public and private funding for culture, and what kind of impact can major cultural events, such as Documenta 14, have on Athens:

What is the imprint of culture in Athens life today?

The crisis has hit a large part of Athens and Greece´s cultural industry, while public funding for culture has shrunk. Yet, lifestyle and urban dynamics associated with Athens, such as the transformation of the city centre through entertainment and culture, have not changed much when compared to what was happening fifteen or ten years prior to the crisis. At the same time, Athens remains closely linked to globalized culture, without however being in its avant-garde. A new element in Athenian life is the multiplication of artistic initiatives coming from below, promoted by well-educated young artists with a cosmopolitan outlook. These initiatives often have a socio-political orientation, which was less the case in the years before the crisis. Their emergence coincides with that of social solidarity endeavours; these represent efforts at self-organization, following the weakening of public structures of support.

Another important element marking Athenian cultural life today is the strengthening of the role of private cultural foundations, either through the funding of cultural activities – often projects by young artists – or through the establishment of new metropolitan infrastructures. Finally, it should be noted that Athens has the sad privilege of attracting international attention because of the crisis; hosting Documenta 14 for the first time in the Greek capital is a typical example of this.

During the 1960s, Athens basically consisted of an agglomeration of families resettled here from the countryside. What does the Greek capital represent today? What does the way that leisure and entertainment have evolved tell us about the changes in the organization of life and social relations in the city?

In the first decades following World War II, the population of Athens tripled as a result of the great migration from rural areas to the capital. This demographic transformation was also the cause of a cultural transformation in the city. The new populations that settled in Athens gradually adopted urban lifestyles, which were themselves changing due to economic growth and rise in consumer spending. There were, however, other elements that ran against the shaping of urban cultures, such as social class divisions, cultural and social links with places of origin in the provinces, and the relatively limited number of cultural infrastructures in Athens.

Things changed a great deal since the late 1970s. The rural exodus was now over and there were new generations that were Athens born-and-bred, who developed an identity-based interest in Athens, its city centre, its history – or at least in the idealized images of the Athenian past – and in the relationship between Athens and other metropolises of the Western world. This interest has played a fundamental role in the “return” of the middle class to the city centre since the early 1990s. The cultural transformation of the city centre has brought about two trends: the rediscovery of the Athenian past and attempts to associate Athenian cultures with trends in European and American metropolises. Going through media articles of the 1990s, it becomes evident that the city of Athens is increasingly compared with international capitals in terms of culture, lifestyle, entertainment, etc., a pattern that is still valid today.

At the same time, since the 1980s, the public and private sector have continued to add to the city’s metropolitan cultural infrastructure, the latest three significant additions being the new National Museum of Contemporary Art, the Onassis Cultural Centre, and the National Opera and National Library at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center complex. These institutions play a fundamental role in shaping and reshaping Athenian cultures; they constitute public spaces that “educate” the public and contribute in the development of a collective consciousness. They also make it possible to better integrate Athens into international cultural flows, thanks to their capacity to host demanding events. However, these centres also increase the centralization of cultural production and consumption, creating a kind of control over artistic opportunities that did not exist before. The relationship between public and private sectors is fundamental in this respect.

The construction of the new facilities of the National Opera and the National Library. Source: Athens Social Atlas

In fact, in Athens and generally in Greece, as far as culture is concerned, there exists a particular “institutional order”: the state monopolises antiquities, identified as an important area of national identity, while private agents and members of cultural elites have invested symbolically and materially in other cultural fields (popularization of science, modern art, contemporary art). This division has its historical roots in the Greek Diaspora of the 19th century and continues to persist, in more or less different terms, to the present day. It is, in fact, impossible to understand the cultural life of Athens from an institutional point of view without taking into consideration this division of labour between the state and the private sector. Naturally, there are no impregnable boundaries; yet there is a strong tradition that explains why, for example, the state delayed the creation of a Museum of Modern Art and a Museum of Contemporary Art, and why we are witnessing today the birth of new private cultural institutions like the Onassis Cultural Centre.

Another development that should be mentioned is the relative shrinking of class divisions in culture. The National Centre of Social Research recently completed a survey under the scientific direction of Dimitris Emmanuel, based on 2,500 questionnaires about cultural consumption in Athens. This study has shown that while upper classes are more likely to consume goods of so-called “high culture” (classical music, jazz, experimental theatre and dance, alternative cinema etc.), what we call “pop culture” (international and Greek popular music, commercial cinema and theatre) is addressed to all social classes, with the partial exception of the most disadvantaged strata. One reason for this is that after decades of social mobility, the social structure of the city changed as the working class shrunk. Moreover, in Athens you have places that function as “melting pots” frequented by people from different social classes sharing common cultural experiences.

The escape to the suburbs began at the end of the 70’s and has not stopped since; at the same time we are witnsessing a boom of cultural and entertainment activities in the otherwise “decayed” centre of Athens. Would you like to comment? Is this a precursor of gentrification in Athens?

All this has undoubtedly transformed and is still transforming the centre of Athens, giving the city a cultural verve and nightlife that has been almost constantly changing for the past two or three decades. But can we say that this is gentrification? With this term we usually mean a process of transformation of a neighborhood, often through the establishment of cultural and entertainment activities, which is followed then by the influx of new, more affluent residents. These new residents are usually middle class and their presence increases rental and real estate values, which in turn, leads to the exodus of the area’s original, poorer inhabitants. Researchers, such as Thomas Maloutas and others, studying the housing market and demographic movements in decayed downtown neighborhoods in Athens, have not found evidence of a massive resettlement by new middle class residents. Thus there is no gentrification process, in the strict sense of the term; there is a process of economic reinvestment and reintegration of certain neighbourhoods into urban mobility, but typically gentrification describes something else that is not found, at least not to a large extent, in the centre of Athens.

So, since we don’t have gentrification, how has the growth of entertainment (bars, restaurants, cafes) and cultural activities (theaters, galleries, cultural venues) changed the centre of Athens? What has been the impact of the economic crisis?

The economic crisis has unevenly affected cultural and entertainment activities. As a recent statistical study carried out by a Panteion University scientific team (V. Avdikos, M. Michailidou, G. Klimis, A. Mimis) revealed, sectors such as publishing and media were severely struck. In contrast, entertainment, bars and restaurants, as is visible in downtown Athens, carry on. There are three reasons for this: Firstly, Athens increasingly attracts more and more tourists as a result of the rehabilitation of its historic centre, a growing offer of cultural activities, and the geopolitical turmoil affecting tourism in neighbouring countries; Secondly, as statistics show, in times of crisis, local consumers do reduce their spending in entertainment as much as they do in other areas, such as clothing. This shows the psychological value of entertainment and its importance in maintaining a social life. Finally, entertainment offers entrepreneurial opportunities during a crisis: to open a bar or a cafe, you don’t need specialized knowledge and you can rely mainly your own resources (personal work, personal networks, etc).

Can a major international exhibition such as Documenta influence the identity of a city like Athens?

Documenta is a large-scale event that embraces the majority of important cultural spaces of the city, attracts international visitors and provides visibility for Athens. However, I do not think that an event, however important, can change the cultural identity of a city. Cultural identity depends on more structural conditions, such as the existence of local artistic scenes whose products can be exported abroad, the involvement of a more or less broad public that is educated and interested in culture, the availability of public and private funding for cultural activities and the existence of cultural infrastructures. An event like Documenta can work as a catalyst when some of the above structural conditions are met, but this is as far as it goes.

One should address with certain realism the cultural impact Documenta had on Athens. In general, such exhibitions could have symbolic and /or organizational impact. From an organizational point of view, Documenta has created a precedent, in the sense that it has shown to the international artistic world that Athens has the infrastructure to host such a big event. This is important, but it should not be overestimated. From a symbolic point of view, I fear that the impact is more limited. Documenta came to Athens under the slogan “learning from Athens”. This interest in “learning” from Athens is related to the crisis, rendering the Greek capital as an almost exotic or experimental space in socio-political terms. In fact, Documenta’s interest in Athens is part of a wider international interest from journalists, researchers and activists who visit ‘Athens of the crisis’, write about it etc. From this point of view, there is nothing original in Documenta’s concept of “learning from Athens”.

One should address with certain realism the cultural impact Documenta had on Athens. In general, such exhibitions could have symbolic and /or organizational impact. From an organizational point of view, Documenta has created a precedent, in the sense that it has shown to the international artistic world that Athens has the infrastructure to host such a big event. This is important, but it should not be overestimated. From a symbolic point of view, I fear that the impact is more limited. Documenta came to Athens under the slogan “learning from Athens”. This interest in “learning” from Athens is related to the crisis, rendering the Greek capital as an almost exotic or experimental space in socio-political terms. In fact, Documenta’s interest in Athens is part of a wider international interest from journalists, researchers and activists who visit ‘Athens of the crisis’, write about it etc. From this point of view, there is nothing original in Documenta’s concept of “learning from Athens”.

What we should comment on is the way in which Documenta integrates ‘Athens of the crisis’ in its symbolic strategies. According to organizers, choosing Athens as the second site for Documenta 14, utilizes the “tension between Athens and Kassel” in order to create “a critical space for the design of a collaborative, artistic and activist project beyond the nation-state and enterprises”. For Documenta 14 itself, this is important because it renews its artistic-cultural identity by referencing resistance against neoliberalism, as Documenta 11 did, when, from a postcolonial perspective, it included non-European cities in its programme. Athens also provided a framework for creating site-specific art.

My point is that Documenta utilizes “Athens of the crisis” in artistic and identity strategies that are addressed to the international art world and not to local society. Documenta’s interventions in local social life are insignificant from the point of view of the inhabitants (one can see for example the small Documenta restaurant which offers free meals at Kotzia square, in a city where various organizations have been offering thousands of free meals since the beginning of the crisis). In addition, although several Documenta works have a socio-political content, they employ, like a good part of contemporary art in general, an artistic language inaccessible to the general public. In fact, I think that if there is a symbolic impact of Documenta on Athens, it concerns mostly young Greek artists: because of the crisis, Greek artists have fewer opportunities to travel abroad and Documenta was an opportunity for them to attend a major contemporary art event and to get to know international trends right here in Greece.

*Interview to Ioulia Livaditi, Magdalini Varoucha / Translation from French Ioulia Livaditi, Magdalini Varoucha

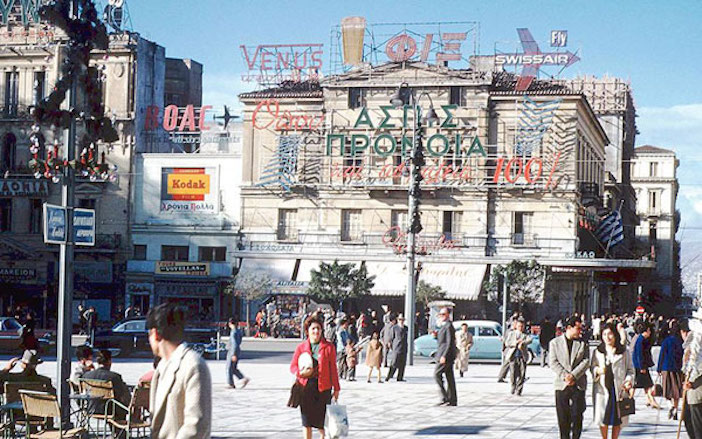

Monastiraki square, Athens 1954, Photo by Robert McCabe

Monastiraki square, Athens 1954, Photo by Robert McCabe